The COVID-19 pandemic has posed a threat to hospital capacity due to the high number of admissions, which has led to the development of various strategies to release and create new hospital beds. Due to the importance of systemic corticosteroids in this disease, we assessed their efficacy in reducing the length of stay (LOS) in hospitals and compared the effect of 3 different corticosteroids on this outcome.

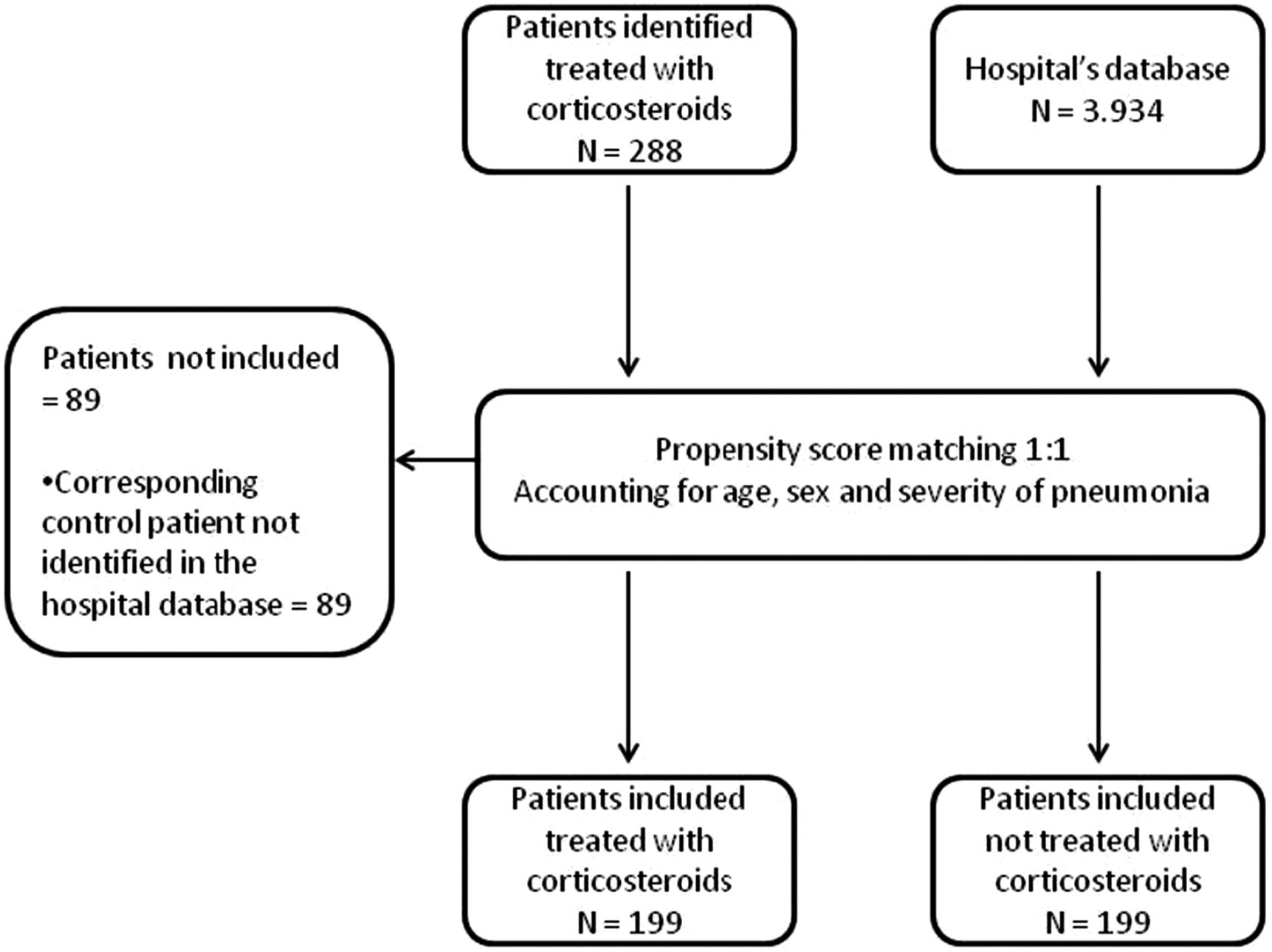

MethodsWe conducted a real-world, controlled, retrospective cohort study that analysed data from a hospital database that included 3934 hospitalised patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in a tertiary hospital from April to May 2020. Hospitalised patients who received systemic corticosteroids (CG) were compared with a propensity score control group matched by age, sex and severity of disease who did not receive systemic corticosteroids (NCG). The decision to prescribe CG was at the discretion of the primary medical team.

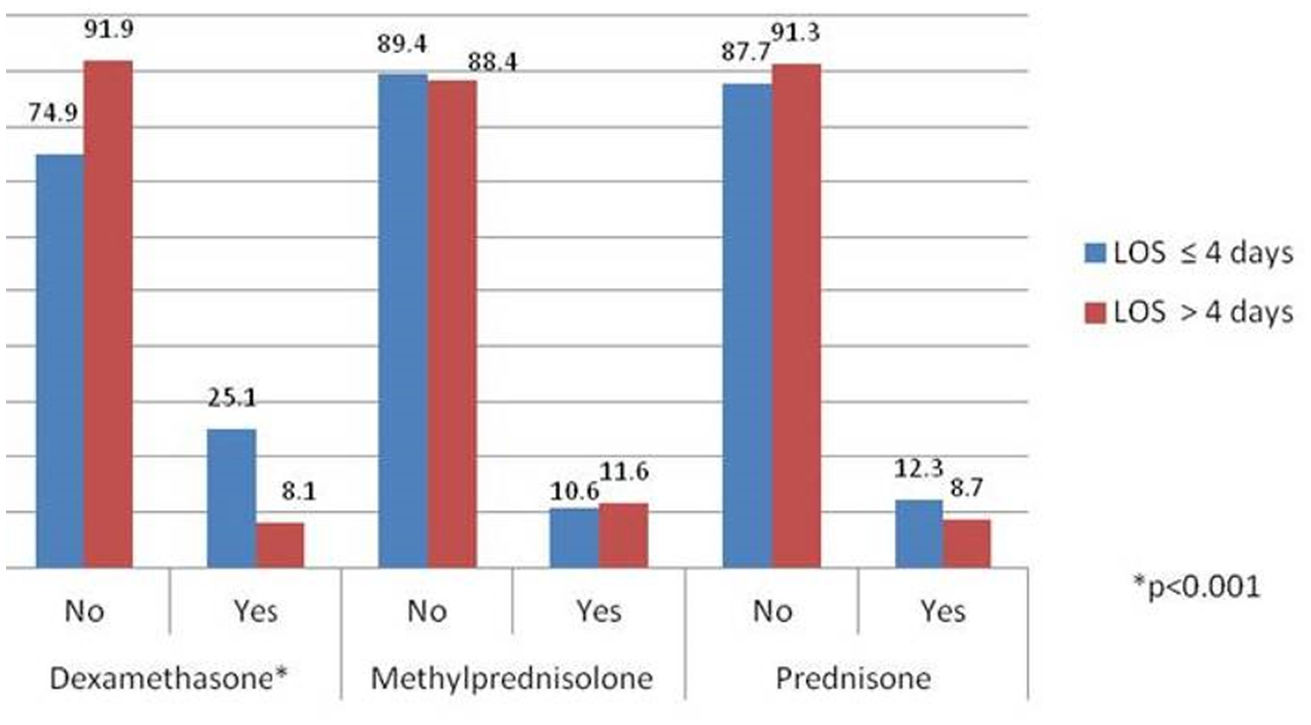

ResultsA total of 199 hospitalized patients in the CG were compared with 199 in the NCG. The LOS was shorter for the CG than for the NCG (median = 3 [interquartile range = 0–10] vs. 5 [2–8.5]; p = 0.005, respectively), showing a 43% greater probability of being hospitalised ≤ 4 days than > 4 days when corticosteroids were used. Moreover, this difference was only noticed in those treated with dexamethasone (76.3% hospitalised ≤ 4 days vs. 23.7% hospitalised > 4 days [p < 0.001]). Serum ferritin levels, white blood cells and platelet counts were higher in the CG. No differences in mortality or intensive care unit admission were observed.

ConclusionsTreatment with systemic corticosteroids is associated with reduced LOS in hospitalised patients diagnosed with COVID-19. This association is significant in those treated with dexamethasone, but no for methylprednisolone and prednisone.

El COVID-19 supuso una amenaza para la capacidad hospitalaria por el elevado número de ingresos, lo que llevó al desarrollo de diversas estrategias para liberar y crear nuevas camas hospitalarias. Dada la importancia de los corticoides sistémicos en esta enfermedad, se evaluó la eficacia de estos en la reducción de la duración de la estancia hospitalaria (LOS) y se comparó el efecto de tres corticosteroides diferentes sobre este resultado.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio en vida real de cohorte retrospectivo, controlado que analizó una base de datos hospitalaria que incluyó 3.934 pacientes hospitalizados diagnosticados con COVID-19 en un hospital terciario de abril a mayo de 2020. Se comparó un grupo de enfermos que recibieron corticosteroides sistémicos (CG) frente a un grupo de control que no recibió corticosteroides sistémicos (NCG) emparejado por edad, sexo y gravedad de la enfermedad mediante una puntuación de propensión. La decisión de prescribir CG dependía principalmente del criterio del médico responsable.

ResultadosSe compararon un total de 199 pacientes hospitalizados en el GC con 199 en el GNC. La LOS fue más corta para el GC que para el NCG (mediana = 3 [rango intercuartílico = 0-10] vs. 5 [2-8,5]; p = 0,005, respectivamente), mostrando un 43% más de probabilidad de ser hospitalizado ≤ 4 días que > 4 días cuando se usaron corticosteroides. Además, esta diferencia solo la mostraron aquellos tratados con dexametasona (76,3% hospitalizados ≤ 4 días vs. 23,7% hospitalizados > 4 días [p < 0,001]). Los niveles de ferritina sérica, glóbulos blancos y plaquetas fueron más elevados en el GC. No se observaron diferencias en la mortalidad ni en el ingreso a la unidad de cuidados intensivos.

ConclusionesEl tratamiento con corticosteroides sistémicos se asocia con una disminución de la estancia hospitalaria en pacientes hospitalizados con diagnóstico de COVID-19. Esta asociación es significativa en aquellos tratados con dexametasona, no así en metilprednisolona o prednisona.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) continues to be responsible for a high number of hospitalizations. 12%–20% of patients with COVID-19 need hospitalisation due to a severe illness causing acute respiratory failure that can develop even just a few hours after the beginning of the dyspnoea1,2. Mortality is extremely high in this subgroup of patients, with a reported rate of 20%–52%3,4.

These alarming statistics have posed an enormous threat to the capacity of hospitals, which have had to reduce the use of hospital beds for non-COVID-19 illnesses and expand the number and availability of ICU hospital beds as well as providing other resources and amenities. In fact, the demand for available beds was so high in Madrid during the first pandemic surge that it was necessary to convert hotels to hospital-hotels5 and to adapt an exhibition space into a provisional hospital. In fact, a new pandemic hospital has been constructed specifically for this difficult situation, and throughout the Spanish territory numerous field hospitals have been built.

To improve the data on treatments and outcomes, several therapies for hospitalised patients have been evaluated. Thus far, corticosteroids3, together with anticoagulation, the antiviral remdesivir, or immunomodulators such as tocilizumab or the Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib have shown some efficacy in randomised clinical trials, but many others are under investigation6.

Regarding systemic corticosteroids, experience in other viral acute respiratory distress syndromes (ARDS), such as Middle East respiratory syndrome, severe acute respiratory syndrome and influenza, had shown delayed viral clearance, no benefit and even potential injury7–9. Therefore, although corticosteroids were not recommended for COVID-19 treatment in the early phases of the pandemic10, we now know that in the inflammatory phase of severe COVID-19 they can reduce proinflammatory and augment anti-inflammatory cytokines, as well as improve lung barrier integrity and microcirculation11–13. Fortunately, the evidence is growing, and in the RECOVERY randomised trial, dexamethasone demonstrated a reduction in mortality in patients with respiratory failure3. In addition, in several observational studies, the benefits of corticosteroids in regard to delaying intensive care unit (ICU) admission, shortening mechanical ventilator support14, and even reduced mortality have been observed14,15.

Dexamethasone is a well-known drug with more than 60 years of clinical use. Its therapeutic potential comes from several actions. First, it binds to glucocorticoid receptors present in the cell cytoplasm, which are responsible for the initiation of immune cells responses that lead to proinflammatory suppression of several cytokines, some of which are related to COVID-19 progression. It also increases the gene expression of interleukin (IL)-10, which is an anti-inflammatory cytokine mediator. Second, it inhibits neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells, preventing the release of lysosomal enzymes and chemotaxis at the site of inflammation, as well as inhibiting macrophage activation, one of the main authors of cytokine storms in COVID-19, which in turn is the landmark of severe COVID-19. Additionally, dexamethasone has other important benefits, such as its low-cost, easy availability and its long-lasting effect that allows a once-a-day regimen11,16.

Given the positive results of previously mentioned studies on corticosteroids, we suspected that corticosteroids also could shorten the hospital length of stay (LOS), thus reducing the consumption of resources and increasing available beds for other patients who need them. However, no study has focused on this outcome. Furthermore, while the evidence has been accumulating on dexamethasone, other groups of corticosteroids have not yet been evaluated.

Thus, we focused on the first wave of the pandemic, when corticosteroids were beginning to be used, and we compared patients who received corticosteroids with patients who did not. We conducted a real-world study in which we aimed to determine the efficacy of corticosteroids in shortening the LOS in patients with COVID-19 compared with patients who did not receive corticosteroids. In addition, we evaluated which group of corticosteroids was the most effective in reducing the LOS.

MethodsStudy design and objectivesThis was a real-world, controlled, retrospective cohort study. Our main objective was to determine the impact of systemic corticosteroids on the LOS in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. We also evaluated whether the use of corticosteroids was associated with the occurrence of severe complications of COVID-19, such as death and admission to the ICU. Finally, we aimed to assess which specific subgroup of corticosteroids acts most effectively on theses outcomes.

Patient population and COVID-19 databaseWe included all individuals, 18 years or older, who were hospitalised in a 1286-bed hospital in Madrid (La Paz University Hospital) with a diagnosis of COVID-19 from April to May 2020, who received systemic corticosteroids (corticosteroid therapy group [CG]). Due to the limited evidence on the use of systemic corticosteroids in this disease until this time, their prescription mainly depended on the physicians’ previous experience in their use.

Patients not hospitalised or discharged from the emergency department after a stay of less than 24 h were not included. A control group of patients who did not require systemic corticosteroid treatment (non-corticosteroid therapy group [NCG]) was recruited from a hospital database that comprised all patients hospitalised with a COVID-19 diagnosis during the same period. The characteristics of this database have been previously published17 and included 3934 patients consecutively treated in the Emergency Department of an University Hospital between February 25, 2021 and June 16, 2021, and who were later hospitalised. The database (called COVID@HULP) includes 372 variables, grouped into demographics, medical history, infection exposure history, symptoms, complications, treatments (excluding clinical trials) and disease progression during hospitalisation. For this study, we extracted age, sex, smoking status, transmission, comorbidities, symptoms on admission, severity of disease, complications, ICU admission and death during hospitalisation. The severity of disease was evaluated according to the Spanish Official Document on the management of COVID-19. It considered mild pneumonia as oxygen saturation higher than 90%, with no signs of severity and a CURB-65 pneumonia severity score lower than 2; and severe COVID-19 pneumonia as organ failure, oxygen saturation lower than 90% or respiratory rate higher than 3018.

Patients (with or without systemic corticosteroid treatment) were matched 1:1 by age, sex and severity of disease. Matching was performed by statisticians of the Central Clinical Research Unit who were blinded to completion of the data.

Laboratory results (haematology, biochemistry, microbiology) were extracted from various hospital data management systems, and information regarding the drugs used during hospitalisation was extracted from the electronic prescription system.

Patients with corticosteroids were identified using the computerised physician order entry (CPOE) program to make prescriptions. The task of identifying patients treated with corticosteroids was performed by a pharmacist with high experience using the CPOE program.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of La Paz University Hospital (PI-4455).

OutcomesThe main outcomes were LOS in hospital, death and admission to the ICU. We also evaluated differences between the CG and NCG as well as the development of complications during hospitalisation.

Statistical analysisIn the first part of the analysis, baseline characteristic data on both groups (CG and NCG) were evaluated. In the second part, analyses were focused on the subgroups of corticosteroids used. Patients in both groups were propensity score matched 1:1, accounting for age, sex and severity of disease. Quantitative variables were expressed as medians with interquartile range (IQR). For categorical variables, frequencies and proportions were used. Prior to the analyses, a normality analysis was performed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. For the parametric analysis, Student’s t-test was used, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for non-parametric analyses. For correlations between quantitative variables, Spearman’s correlation was employed. For the associations between qualitative variables, the chi-squared test (or Fisher's test when necessary) was used. Finally, to investigate the association between corticosteroids and the LOS, we employed a logistic regression analysis. For this purpose, the hospital LOS was dichotomised into ≤ 4 and > 4 days, given it corresponded to the median of the included population. Statistical significance was set at a p-value ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.4.

ResultsBaseline characteristics of the included patientsA total of 288 hospitalised patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were identified as treated with corticosteroids during the study period. Of these, 89 were not included because of the inability to find a control participant in the hospital’s database after applying the propensity score matching. Ultimately, 199 patients allocated to the CG and 199 patients in the NCG were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

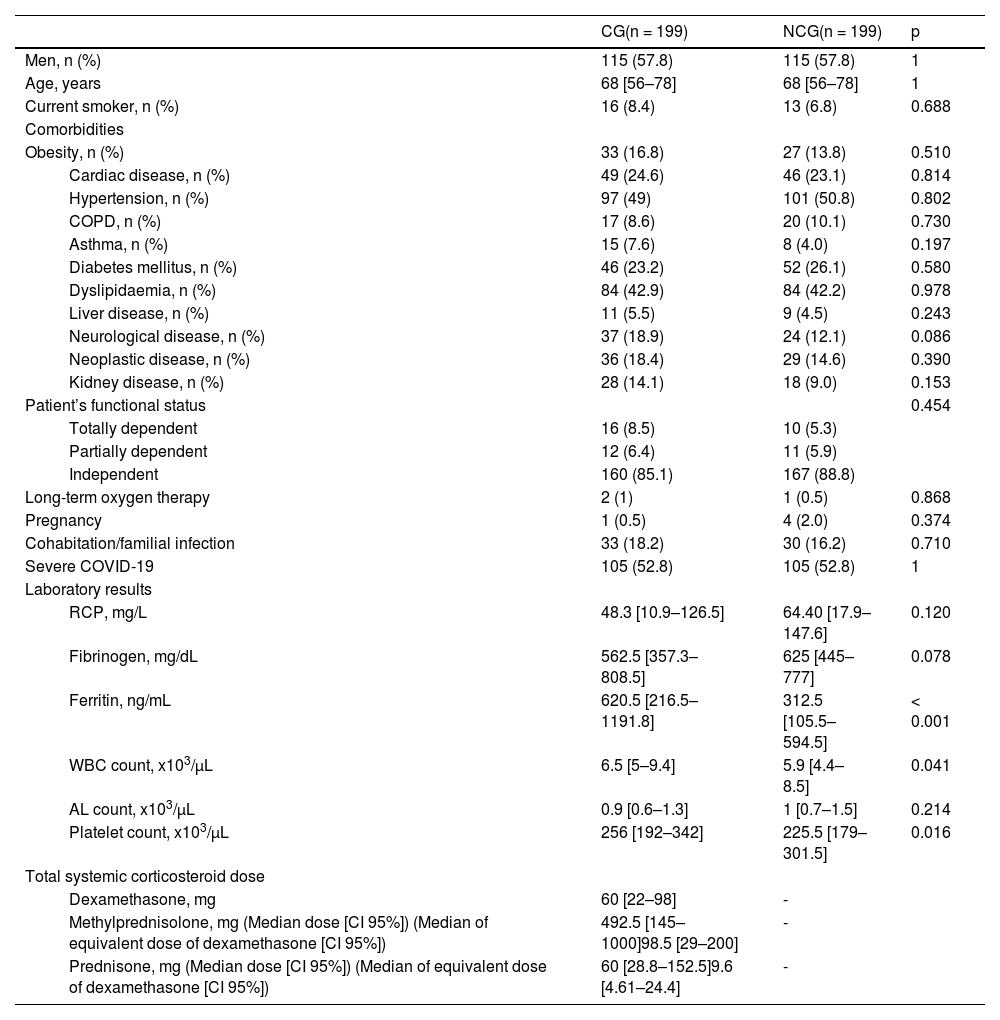

The distributions of comorbidities were not different when comparing the CG with the NCG. Regarding the systemic inflammatory response to COVID-19, only serum ferritin levels (620.5 [IQR 216.5–1191.8] vs 312.5 [IQR 105.5–594.5]; p < 0.001), white blood cell count (6.5 [IQR 5–9.4] vs 5.9 [IQR 4.4–8.5]; p = 0.041) and platelets (256 [IQR 192–342] vs 225.5 [IQR 179–301.5]; p = 0.016) were significantly higher in the CG compared with the NCG. Comparisons between both groups are detailed in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of hospitalised patients diagnosed with COVID-19 treated or not with systemic corticosteroids.

| CG(n = 199) | NCG(n = 199) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men, n (%) | 115 (57.8) | 115 (57.8) | 1 | |

| Age, years | 68 [56–78] | 68 [56–78] | 1 | |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 16 (8.4) | 13 (6.8) | 0.688 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Obesity, n (%) | 33 (16.8) | 27 (13.8) | 0.510 | |

| Cardiac disease, n (%) | 49 (24.6) | 46 (23.1) | 0.814 | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 97 (49) | 101 (50.8) | 0.802 | |

| COPD, n (%) | 17 (8.6) | 20 (10.1) | 0.730 | |

| Asthma, n (%) | 15 (7.6) | 8 (4.0) | 0.197 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 46 (23.2) | 52 (26.1) | 0.580 | |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 84 (42.9) | 84 (42.2) | 0.978 | |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 11 (5.5) | 9 (4.5) | 0.243 | |

| Neurological disease, n (%) | 37 (18.9) | 24 (12.1) | 0.086 | |

| Neoplastic disease, n (%) | 36 (18.4) | 29 (14.6) | 0.390 | |

| Kidney disease, n (%) | 28 (14.1) | 18 (9.0) | 0.153 | |

| Patient’s functional status | 0.454 | |||

| Totally dependent | 16 (8.5) | 10 (5.3) | ||

| Partially dependent | 12 (6.4) | 11 (5.9) | ||

| Independent | 160 (85.1) | 167 (88.8) | ||

| Long-term oxygen therapy | 2 (1) | 1 (0.5) | 0.868 | |

| Pregnancy | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.0) | 0.374 | |

| Cohabitation/familial infection | 33 (18.2) | 30 (16.2) | 0.710 | |

| Severe COVID-19 | 105 (52.8) | 105 (52.8) | 1 | |

| Laboratory results | ||||

| RCP, mg/L | 48.3 [10.9–126.5] | 64.40 [17.9–147.6] | 0.120 | |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 562.5 [357.3–808.5] | 625 [445–777] | 0.078 | |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 620.5 [216.5–1191.8] | 312.5 [105.5–594.5] | < 0.001 | |

| WBC count, x103/μL | 6.5 [5–9.4] | 5.9 [4.4–8.5] | 0.041 | |

| AL count, x103/μL | 0.9 [0.6–1.3] | 1 [0.7–1.5] | 0.214 | |

| Platelet count, x103/μL | 256 [192–342] | 225.5 [179–301.5] | 0.016 | |

| Total systemic corticosteroid dose | ||||

| Dexamethasone, mg | 60 [22–98] | - | ||

| Methylprednisolone, mg (Median dose [CI 95%]) (Median of equivalent dose of dexamethasone [CI 95%]) | 492.5 [145–1000]98.5 [29–200] | - | ||

| Prednisone, mg (Median dose [CI 95%]) (Median of equivalent dose of dexamethasone [CI 95%]) | 60 [28.8–152.5]9.6 [4.61–24.4] | - | ||

Data expressed as median [interquartile range] or number (percentage).

Comparisons between groups by unpaired samples using Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test and chi-squared test. Abbreviations: AL = absolute lymphocyte; CG = corticosteroid group; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NCG = non-corticosteroid group; RCP = C-reactive protein; WBC = white blood cell.

In the group treated with corticosteroids, the median age was 68 (IQR 56–78) and 57.8% were men. The total systemic corticosteroid dose classified according to the group of corticosteroids were 60 mg (IQR 22–98) for dexamethasone, 492.5 mg (IQR 145–1000) for methylprednisolone and 60 mg (IQR 28.8–152.5) for prednisone (Table 1). The amounts of corticosteroids employed were converted to an equivalent dose of dexamethasone, resulting in a total median dexamethasone dose of 12 mg (IQR 22–98) (Table 1).

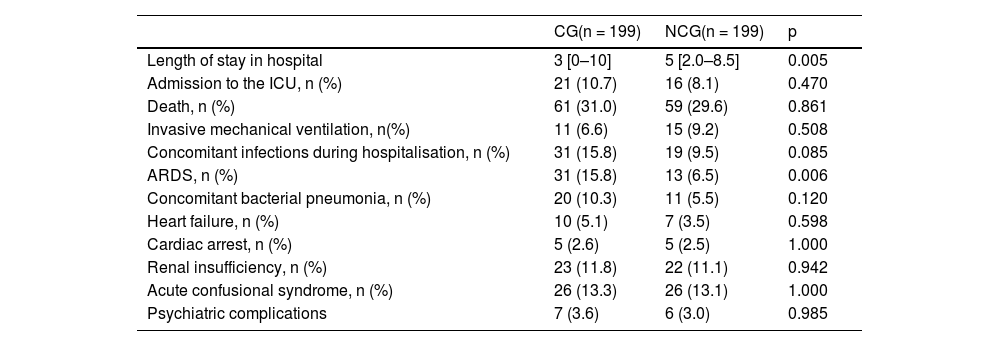

Outcomes associated with the prescription of corticosteroidsThe hospital LOS was statistically shorter in the CG than in the NCG (3 [IQR 0–10] vs. 5 [IQR 2.0–8.5] days; p = 0.005). This difference might not be associated with higher mortality, given the mortality rate was not different between the groups (31% vs. 29.6%; p = 0.861); or with a higher severity of the disease at the time of hospital admission, because severity was considered in the matching process of the NCG with the CG. In fact, the CG had a higher rate of ARDS complications during hospitalisation than the NCG (p = 0.006). No differences were observed in the rate of admission to the ICU or in the development of other complications during hospitalisation (Table 2). In addition, when converting the doses of the different types of corticosteroids into equivalent doses of dexamethasone, this dose was well correlated with LOS. (r = 0.31; p = 0.058).

Outcomes among hospitalised patients diagnosed with COVID-19 treated or not with systemic corticosteroids.

| CG(n = 199) | NCG(n = 199) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay in hospital | 3 [0–10] | 5 [2.0–8.5] | 0.005 |

| Admission to the ICU, n (%) | 21 (10.7) | 16 (8.1) | 0.470 |

| Death, n (%) | 61 (31.0) | 59 (29.6) | 0.861 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, n(%) | 11 (6.6) | 15 (9.2) | 0.508 |

| Concomitant infections during hospitalisation, n (%) | 31 (15.8) | 19 (9.5) | 0.085 |

| ARDS, n (%) | 31 (15.8) | 13 (6.5) | 0.006 |

| Concomitant bacterial pneumonia, n (%) | 20 (10.3) | 11 (5.5) | 0.120 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 10 (5.1) | 7 (3.5) | 0.598 |

| Cardiac arrest, n (%) | 5 (2.6) | 5 (2.5) | 1.000 |

| Renal insufficiency, n (%) | 23 (11.8) | 22 (11.1) | 0.942 |

| Acute confusional syndrome, n (%) | 26 (13.3) | 26 (13.1) | 1.000 |

| Psychiatric complications | 7 (3.6) | 6 (3.0) | 0.985 |

Data expressed as median [interquartile range] or number (percentage). Comparisons between groups by unpaired samples Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test and chi-squared test. Abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; GC = corticosteroid group; ICU = intensive care unit; NCG = non-corticosteroid group.

The LOS was dichotomised into ≤ 4 and > 4 days, which corresponded to the median of the included population. The logistic regression model revealed that the prescription of corticosteroids was associated with a 43% greater probability of being hospitalised ≤ 4 days compared with the NCG (OR 0.57 [0.37-0.87; p = 0.009]).

Analysis of the impact of the type of corticosteroid on the length of hospital stayFor this purpose, we only included patients treated with a single group of corticosteroids throughout their hospitalisation. Differences were only noticed in those treated with dexamethasone, in which 76.3% were hospitalised ≤ 4 days and 23.7% stayed > 4 days (p < 0.001). In the other groups, no differences in LOS were observed (Fig. 2).

DiscussionThe COVID-19 pandemic has meant, especially during the first wave, the near paralysis of hospitalisations for non-COVID-19 health problems as well as for non-urgent surgeries, in order to deal with all the patients with serious COVID-19 who required hospital admission. In addition, although the number of ICU beds has been significantly increased, in some time periods it was still insufficient19. Therefore, reducing the hospital LOS was (and still is) profoundly beneficial in helping cope with new patients who need hospitalisation.

In the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, we had a period in which corticosteroids were not routinely recommended and were even contraindicated, after which the first evidence supporting their use was reported18. This real-world controlled retrospective cohort study suggests that corticosteroids, specifically dexamethasone, reduced the LOS in patients with higher inflammation markers compared with the control group. As we have seen, patients in the CG expressed higher levels of platelets and white blood cells, and they had two times higher ferritin levels than those in the NCG. Severe COVID-19 is caused by an excessive systemic increase of cytokines and chemokines in the patient, also called a “cytokine storm”, which leads to immunopathological lung damage and diffuse alveolar injury, with the development of ARDS and death20. In this subgroup of patients, a hyperinflammatory phenotype has been described in which the serum concentrations of inflammatory and coagulation markers (including ferritin, D-dimer, and C-reactive protein), as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-2R, IL-6, IL-10 and tumour necrosis factor-α) are increased, accompanied by reduced lymphocytes and neutrophils with immunometabolic reprogramming13,21,22. Given corticosteroids are potent immunomodulatory drugs that can break the inflammatory feedforward loop in some individuals 11, as we have seen in the CG group, those with higher inflammation might obtain a greater benefit in terms of LOS11–13,21.

This investigation occurred during a time period in which the first evidence on the benefit of corticosteroids in COVID-19 was being published. At the time of this study, given the data were heterogeneous and we did not know which corticosteroid type was the most appropriate, our hospital protocol allowed us to choose between the 3 corticosteroids described based on the criteria of the attending physicians. We have shown that, while dexamethasone reduces the LOS, methylprednisolone and prednisone did not achieve this outcome.

Most of the evidence accumulated to date on COVID-19 is on dexamethasone. Indeed, the largest randomised study with corticosteroids in severe COVID-19 was the RECOVERY trial, in which it was observed that dexamethasone administration led to a reduction in mortality in patients with respiratory failure3. This outcome has been further supported in 2 meta-analyses that included a high number of critically ill patients with heterogeneous data23,24. Methylprednisolone has also been shown better clinical outcomes, to increase ventilator-free days, and a lower mortality rate in moderate to severe COVID-1914,25,26. In fact, there have been published two randomized trials with hospitalized COVID-19 patients in which methylprednisolone demonstrated a lower ventilator use and shorter length of hospital stay compared to dexamethasone27,28.

It is important to note that, when assessed both clinical trials, the applied dose of methylprednisolone was much higher than that of dexamethasone, which makes difficult to draw conclusions regarding whether methylprednisolone is better option than methylprednisolone, or if the higher dose of corticosteroid is the reason for the improvement in this group of patients. In the other hand, when comparing the results of our study with other series, we have several observations. First, although this cohort exhibited a higher mortality rate than that of the RECOVERY trial3, it is within the range reported in other series2–4. We must consider the selection bias of randomised clinical trials, in which the most severe patients could be excluded. Fortunately, mortality might be decreasing as the pandemic progresses. Second, there was also a lower proportion of patients who were admitted to the ICU compared with other cohorts3,4,29. This difference is probably due to the participation of the Intermediate Respiratory Care Units within the Pulmonary Department in our hospital during the pandemic19,30. Noninvasive ventilation and other noninvasive respiratory support, such as high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy, have played an important role here1,29,31. These therapies could be applied together with close cardiorespiratory monitoring in these units to try to reduce or delay ICU admissions among patients who require noninvasive respiratory support in a crisis situation, as well as to manage early discharges from the ICU and for those patients who were ineligible for admission to the ICU due to comorbidities.

The main strength of our study is that it is a real-world cohort at a time when corticosteroid treatment had started; therefore, corticosteroid treatment groups could be compared in the same clinical setting (one hospital’s treatment protocols, during the same COVID-19 surge). Additionally, we included a control group, matched for sex, age and severity of disease, and representative of a large proportion of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 in Spain.

This study has several potential concerns and limitations. First, it is a single-centre study with a limited sample size, which reduces the external validity of our results and is insufficient to analyse the effect on mortality. However, it is larger than most of the observational studies evaluating corticoid effects14,26,27. Second, although we have explored several baseline characteristics of the patients, due to the design of the study and its retrospective nature, it is possible that confounders have not been evaluated. Nevertheless, the data have been extracted from a complex database that includes a multitude of possible confounders as described previously. Third, the cross-sectional design only permits assessing potential associations or relationships. To evaluate causality, it would be necessary to conduct a longitudinal study with long-term patient follow-up. Additionally, we have no information about the need for oxygen supplementation or noninvasive mechanical ventilation. A final limitation is that, at the time of the compilation of these results, we did not have data on long-term outcomes and mortality, which would further enrich the results. However, these patients are in a post-COVID follow-up consultation, which could resolve this limitation in the future.

In conclusion, corticosteroids, especially dexamethasone, might reduce the length of stay in hospitalised patients, which would have a positive impact on hospital capacity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Author contributions- -

Ester Zamarrón: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

- -

Carlos Carpio: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing

- -

Elena Villamañán: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - review & editing

- -

Rodolfo Álvarez-Sala: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing

- -

Alberto M Borobia: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing - review & editing

- -

Luis Gómez-Carrera: Conceptualization; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing Writing - review & editing

- -

Antonio Buño: Data curation; Formal analysis; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing Writing - review & editing

- -

Concepción Prados: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing

We would like to thank María Jiménez González from the Central Clinical Research Unit at La Paz University Hospital for her collaboration in the statistical analysis.

Funding: The authors declare that they have not received funding to perform this article.

| SURNAME | NAME |

| Committee: | Scientific |

| Arribas | José Ramón |

| Borobia | Alberto M. |

| Carcas-Sansuán | Antonio |

| Frías | Jesús |

| Ramírez | Elena |

| Martín-Quirós | Alejandro |

| Quintana-Díaz | Manuel |

| Mingorance | Jesús |

| Arnalich | Francisco |

| Moreno | Francisco |

| Carlos Figueiras | Juan |

| García-Arenzana | Nicolás |

| Department: | Microbiology |

| Montero Vega | María Dolores |

| Romero Gómez | María Pilar |

| Toro-Rueda | Carlos |

| García-Bujalance | Silvia |

| Ruiz-Carrascoso | Guillermo |

| Cendejas-Bueno | Emilio |

| Falces-Romero | Iker |

| Lázaro-Perona | Fernando |

| Ruiz-Bastián | Mario |

| Gutiérrez-Arroyo | Almudena |

| Girón De Velasco-Sada | Patricia |

| Dahdouh | Elie |

| Gómez-Arroyo | Bartolomé |

| García-Sánchez | Consuelo |

| Guedez-López | Virginia |

| Bloise-Sánchez | Iván |

| Alguacil-Guillén | Marina |

| Liras-Hernández | Maria Gracia |

| Sánchez-Castellano | Miguel Angel |

| García-Clemente | Paloma |

| González-Donapetry | Patricia |

| San José-Villar | Sol |

| de Pablos Gómez | Manuela |

| Gómez-Gil | Rosa |

| Corcuera-Pindado | Maria Teresa |

| Rico-Nieto | Alicia |

| Department: | Pharmacy |

| Herrero | Alicia |

| Medicine | Laboratory |

| Prieto Arribas | Daniel |

| Oliver-Saez | Paloma |

| Mora Corcovado | Roberto |

| Fernández-Calle | Pilar |

| Alcaide Martín | Mª José |

| Díaz-Garzón Marco | Jorge |

| Fernández-Puntero | Belén |

| Nuñez Cabetas | Rocío |

| Crespo Sánchez | Gema |

| Rodriguez Fraga | Olaia |

| Mendez del Sol | Helena |

| Duque Alcorta | Marta |

| Gomez Rioja | Rubén |

| Sanz de Pedro | María |

| Pascual García | Lydia |

| Segovia Amaro | Marta |

| Iturzaeta Sánchez | Jose Manuel |

| Rodriguez Gutiérrez | Mercedes |

| Perez Garcia Morillon | Amparo |

| Martinez Gallego | Miguel Angel |

| Fabre Estremera | Blanca |

| Martinez | Estefaní |

| Moreno Parra | Isabel |

| Rodriguez Roca | Neila |

| Ortiz Sánchez | Daniel |

| Simon Velasco | Manuela |

| Gabriela Tomoiu | Ileana |

| Pizarro Sanchez | Cristina |

| Montero San Martín | Blanca |

| Qasem Moreno | Ana Laila |

| Gómez López | Marta |

| Casares Guerrero | Ismael |

| Buño Soto | Antonio |

| Department: | Radiology |

| Martí de Gracia | Milagros |

| Parra Gordo | Luz |

| Diez Tascón | Aurea |

| Ossaba Vélez | Silvia |

| Pinilla | Inmaculada |

| Cuesta | Emilio |

| Fernández-Velilla | María |

| Torres | Maria Isabel |

| Garzón. | Gonzalo |

| Medicine | Preventive |

| Pérez-Blanco | Verónica |

| Quintás-Viqueira | Almudena |

| San Juan | Isabel |

| Cantero-Escribano | José Miguel |

| Pérez-Romero | César |

| Castro-Martínez | Mercedes |

| Hernández-Rivas | Lucia |

| Pedraz | Teresa |

| Fernández-Bretón | Eva |

| García-Vaz | Claudia |

| Robustillo-Rodela | Ana |

| Medicine | Emergency |

| Torres Santos-Olmo | Rosario María |

| Rivera Núñez | Angélica |

| Fernández Fernández | Ignacio |

| Noguerol Gutiérrez | Marina |

| Martínez Virto | Ana María |

| González Viñolis | Manuel |

| Cabrera Gamero | Regina |

| Mayayo Alvira | Rosa |

| Marín Baselga | Raquel |

| Lo-Iacono García | Victoria |

| Lerín Baratas | Macarena |

| Romero Gallego-Acho | Paloma |

| Reche Martínez | Begoña |

| Tejada Sorados | Renzo |

| Rico Briñas | Mikel |

| Deza Palacios | Ricardo |

| Fabra Cadenas | Sara |

| Arroyo Rico | Isabel |

| Dani Ben-Abdellah | Lubna |

| Labajo Montero | Laura |

| Soriano Arroyo | Rubén |

| López Corcuera | Lorena |

| Calvin García | Elena |

| Martínez Álvarez | Susana |

| López-Tappero Irazábal | Laura |

| Pilares Barco | Martín |

| González Peña | Olga |

| Bejarano Redondo | Guillermina |

| Iglesias Sigüenza | Alberto |

| Tung Chen | Yale |

| Maroun Eid | Charbel |

| Bravo Lizcano | Ruth |

| Silvestre Niño | Miguel |

| Perdomo García | Frank |

| Alonso González | Berta |

| Antón Huguet | Berta |

| Arenas Berenguer | Isabel |

| Cabré-Verdiell Surribas | Clara |

| Marqués González | Francisco |

| Muñoz Del Val | Elena |

| Molina | María Ángeles |

| Cancelliere Fernández | Nataly |

| Pastor Yvorra | Sivia |

| Frade Pardo | Laura |

| López Arévalo | Paloma |

| García | Isabel |

| Medicine | Internal |

| Fernández Capitán | Carmen |

| González Garcia | Juan José |

| Herrero | Juan |

| Quesada Simón | María Angustias |

| Robles Marhuenda | Angel |

| Soto Abanedes | Clara |

| Noblejas Mozo | Ana María |

| Ramos | Juan Carlos |

| Jaras Hernandez | Maria Jesús |

| Martinez Robles | Elena |

| Moreno Fernandez | Alberto |

| Sanchez Purificación | Aquilino |

| Martin Gutiérrez | Juan Carlos |

| Martinez Hernández | Pedro Luis |

| Sancho Bueso | Teresa |

| Lorenzo Hernández | Alicia |

| Gutierrez Sancerni | Belén |

| Salgueiro | Giorgina |

| Martin Carbonero | Luz |

| Mostaza | Jose mAría |

| Martinez-López | María Angeles |

| Hontañon | Victor |

| Menéndez | Araceli |

| Alvarez Troncoso | Jorge |

| Castellano | Arancha |

| Marcelo Calvo | Cristina |

| Vives Beltrán | Ivo |

| Ramos Ruperto | Luis |

| Daroca Bengoa | German |

| Arcos Rueda | María |

| Vasquez Manau | Julia |

| Fernández Cidón | Pelayo |

| Herrero Gil | Carmen Rosario |

| Palmier Peláez | Esmeralda |

| Untoria Tabares | Yeray |

| Lahoz | Carlos |

| Estirado | Eva |

| Hernández | Clara |

| Garcia-Iglesias | Francisca |

| Monteoliva | Enrique |

| Martínez | Mónica |

| Varas | Marta |

| González Alegre | Teresa |

| Valencia | Maria Eulalia |

| Moreno | Victoria |

| Montes. | Maria Luisa |

| Department: | Neumology |

| Alcolea Batres | Sergio |

| Cabanillas Martín | Juan José |

| Carpio Segura | Carlos |

| Casitas Mateo | Raquel |

| Fernández-Bujarrabal Villoslada | Jaime |

| Fernández Navarro | Isabel |

| Fernández Lahera | Juan |

| García Quero | Cristina |

| Hidalgo Sánchez | María |

| Galera Martínez | Raúl |

| García Río | Francisco |

| Gómez Carrera | Luis |

| Gómez Mendieta | María Antonia |

| Mangas Moro | Alberto |

| Martínez Cerón | Elisabet |

| Martínez Redondo | María |

| Martínez Abad | Yolanda |

| Martínez-Verdasco | Antonio |

| Plaza Moreno | Cristina |

| Quirós Fernández | Sarai |

| Romera Cano | Delia |

| Romero Ribate | David |

| Sánchez Sánchez | Begoña |

| Santiago Recuerda | Ana |

| Villasante Fernández-Montes | Carlos |

| Zamarrón De Lucas | Ester |

| Arnalich Montiel | Victoria |

| Mariscal Aguilar | Pablo |

| Falcone | Adalgisa |

| Laorden Escudero | Daniel |

| Prados Sánchez | María Concepción |

| Álvarez-Sala Walther | Rodolfo |

| Care | Intensive |

| García | Andony |

| Arévalo | Cristina |

| Gutiérrez | Carola |

| Yus | Santiago |

| Asensio | Maria José |

| Sánchez | Manolo |

| Manuel Añón | Jose |

| Manzanares | Jesús |

| García De Lorenzo | Abelardo |

| Perales | Eva |

| Civantos | Belén |

| Cachafeiro | Lucía |

| Agrifoglio | Alexander |

| Estébanez | Belén |

| Flores | Eva |

| Hernández | Mónica |

| Millán | Pablo |

| Rodríguez | Montserrat |

| Nanwani | Kapil |

| Intensive | Pediatric |

| Arizcun | Beatriz |

| Pérez-Costa | Elena |

| Rodríguez-Álvarez | Diego |

| Sánchez-Martín | María |

| Quesada | Úrsula |

| Román-Hernández | Carmen |

| Dorao | Paloma |

| Álvarez-Rojas | Elena |

| Menéndez | Juan José |

| Verdú | Cristina |

| Gómez-Zamora | Ana |

| Schüffelmann | Cristina |

| Calderón-Llopis | Belén |

| Laplaza-González | María |

| Río-García | Miguel |

| Amores-Hernández | Irene |

| Rodríguez-Rubio | Miguel |

| de la Oliva | Pedro |

| Department: | Cardiology |

| Ruiz | Jose |

| Rosillo | Sandra |

| González | Oscar |

| Iniesta | Angel |

| Ponz. | Ines |

| Department: | Anesthesiology |

| Muñoz Ramón | José María |

| Hernández Gancedo | María Carmen |

| Uña Orejón | Rafael |

| Sanabria Carretero | Pascual |

| Moreno Gómez-Limón | Isidro |

| Seiz-Martinez | Alverio |

| Guasch-Arévalo | Emilia |

| Martín-Carrasco | Cristina |

| Alvar | Elena |

| Serrá | Lucía |

| Iannuccelli | Fabricio |

| Latorre | Julieta |

| Casares | Sandra |

| Valbuena | Isabel |

| Díaz Díez Picazo | Luis |

| Rodríguez Roca | Cristina |

| Cervera | Omar |

| García de las Heras | Esteban |

| Durán | Pilar |

| Castro | Carmen |

| Manrique de Lara | Carlos |

| Veganzones | Javier |

| López-Tofiño | Araceli |

| Fernandez-Cerezo | Estefanía |

| Zurita | Sergio |

| López-Martinez | Mercedes |

| Prim | Teresa |

| Alvárez Del Vayo | Julía |

| Alcaraz | Gabriela |

| Castro | Luis |

| Yagüe | Julio |

| Díaz-Carrasco | Sofía |

| González-Pizarro | Patricio |

| Montero | Ana |

| Sagra | Francisco Javier |

| Suárez. | Alejandro |

| Care | Palliative |

| Díez Porres | Leyre |

| Varela Cerdeira | María |

| Alonso Babarro | Alberto |

| Entry | Data |

| Abellán Martínez | Francisco |

| Alonso Eiras | Jorge Ignacio |

| Álvarez Brandt | Alejandra |

| Archinà | Martina |

| Arribas Terradillos | Silvia |

| Baselga Puente | Trinidad |

| Barco Núñez | Pilar |

| Barrera López | Natalia Guadalupe |

| Barrera López | Lorena |

| Bartrina Tarrio | Andres |

| Bassani | Gemma |

| Betancort De la Torre | Paula |

| Blanco Bartolomé | Irene |

| Blasco Andres | Celia |

| Brieba Plata | Lucia |

| Cadenas Gota | Fernando |

| Carrera Vázquez | Paloma |

| Cascajares Sanz | Carlota |

| Catino | Arianna |

| Cavallé Pulla | Raquel |

| Ceniza Pena | Daniel |

| Conde Alonso | Ylenia María |

| Currás Sánchez | Laura |

| Daltro Lage | Marcelo |

| Esteban Romero | Ana |

| Fernández Vidal | María Luisa |

| Ferrer Ortiz | Inés |

| de la Fuente Regaño | Lydia |

| Galindo Ballesteros | Pablo |

| Garcia-Bellido Ruiz | Sara |

| García-Mochales Fortún | Carlos |

| Gómez Ballesteros | Teresa |

| Gómez Domínguez | Cecilia |

| González Aguado | Nelsa |

| González García | Sofía |

| Guisández Martín | Jorge |

| Hernández Liebo | Paula Alejandra |

| Hernando Nieto | Raquel |

| Llorente Cortijo | Irene María |

| Marín García | Antonio |

| López Pirez | Pilar |

| Mejuto Illade | Lucía |

| Palma | Marco |

| Peña Hidalgo | Adrian |

| Platero Dueñas | Lucía |

| Pujol Pocull | David |

| Ramírez Verdyguer | Miguel |

| Redondo Gutierrez | Marta |

| Reinoso Lozano | Francisco |

| Rodríguez Revillas | Ana |

| Rodríguez Saenz de Urturi | Alejandro |

| Romero Imaz | Lucía |

| Sánchez Rico | Susana |

| Sánchez Santiuste | Mónica |

| Serrano de la Fuente | Patricia |

| Serrano Martín | Henar |

| Silva Freire | Thamires |

| Soria Alcaide | Eva |

| Suárez Plaza | Andrés Enrique |

| Tejero Soriano | Beatriz |

| Torrecillas Mainez | Andrea |

| Torres Cortés | Javier |

| Valentín-Pastrana Aguilar | María de Las Mercedes |

| Villanueva Freije | Angélica |

| Virgós Varela | Marta |

| Yagüe Barrado | Marta |

| Yustas Benitez. | Natalia |

| Prevention | Risk |

| Núñez | Mª Concepción |

| Pharmacology | Clinical |

| Montserrat | Jaime |

| Queiruga | Javier |

| Rodriguez Mariblanca | Amelia |

| Martínez de Soto | Lucía |

| Urroz | Mikel |

| Seco | Enrique |

| Zubimendi | Mónica |

| Stuart | Stephan |

| Díaz | Lucía |

| García | Irene |

| Management: | Data |

| García Morales | María Teresa |

| Martín-Vega | Alberto |

| Revision | Data |

| Caro | Abel |

| Martínez-Alés | Gonzalo |

| Department | Surname | Name |

| Medicine | Arnalich Fernández | Francisco |

| Fernández Capitán | Carmen | |

| Salgueiro Origlia | Giorgina | |

| Moreno Fernández | Alberto | |

| Laboratory | Buño Soto | Antonio |

| Qasem Moreno | Ana Laila | |

| Prieto Arribas | Daniel | |

| Respiratory Medicine | ÁlvarezSala Walther | Rodolfo |

| Gómez Carrera | Luis | |

| Carpio Segura | Carlos | |

| Mariscal Aguilar | Pablo | |

| Laorden Escudero | Daniel | |

| Plaza Moreno | Cristina | |

| Arnalich Montiel | Victoria | |

| Central Clinical Research Unit | Borobia Pérez | Alberto |

| Jiménez González | María | |

| Nursing | Alegre Segura | Carmen |

| Cuesta Luzzy | Tania | |

| Martínez Gómez | Alejandra | |

| Moreno Juan | Ana María | |

| Rey Iborra | Cristina | |

| Sanz Jiménez | Andrea |

The two authors contributed equally to this work.

The complete list of the members of the COVID@HULP Working Group is provided in the Appendix A.