To determine the prevalence and appropriateness of antimicrobial use in Spanish hospitals through a pharmacist-led systematic cross-sectional review.

MethodA nationwide multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted on 10% of the patients admitted to the participating hospitals on one day in April 2021. Hospital participation was voluntary, and the population was randomly selected. The study sample was made up of patients who, on the day of the study, received at least one antimicrobial belonging to groups J01, J02, J04, J05AB, J05AD or J05AH in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System. The pharmacist in charge made a record and carried out an evaluation of the appropriateness of antimicrobial use following a method proposed and validated by the Pharmaceutical Care of Patients with Infectious Diseases Working Group of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy. The evaluation method considered each of the items comprising antimicrobial prescriptions. An algorithm was used to assess prescriptions as appropriate, suboptimal, inappropriate and unevaluable.

ResultsOne-hundred three hospitals participated in the study and the treatment of 3,568 patients was reviewed. A total of 1,498 (42.0%) patients received antimicrobial therapy, 424 (28.3%) of them in combination therapy. The most commonly prescribed antimicrobials were amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (7.2%), ceftriaxone (6.4%), piperacillin-tazobactam (5.8%), and meropenem 4.0%. As regards appropriateness, prescriptions were considered appropriate in 34% of cases, suboptimal in 45%, inappropriate in 19% and unevaluable in 2%. The items that most influenced the assessment of a prescription as suboptimal were completeness of medical record entries, choice of agent, duration of treatment and monitoring of efficacy and safety. The item that most influences the assessment of a prescription as inappropriate was the indication of antimicrobial agent.

ConclusionsThe method used provided information on the prevalence and appropriateness of the use of antimicrobials, a preliminary step in the design and implementation of actions aimed at measuring the impact of the use of antimicrobials within the antimicrobial stewardship programs.

Conocer la prevalencia y el grado de adecuación del uso de antimicrobianos en los hospitales españoles mediante una revisión sistemática transversal realizada por farmacéuticos.

MétodoEstudio multicéntrico, nacional, transversal sobre el 10% de los pacientes ingresados en los hospitales participantes un día del mes de abril de 2021. La participación de los hospitales fue voluntaria y la selección de la población aleatoria. De la población se disgregó la muestra de estudio, constituida por los pacientes que recibían el día del corte al menos un antimicrobiano perteneciente a los grupos J01, J02, J04, J05AB, J05AD y J05AH del Sistema de Clasificación Anatómica, Terapéutica y Química. Sobre la muestra de estudio, el farmacéutico realizó un registro y evaluación de la adecuación del tratamiento antimicrobiano siguiendo una metódica propuesta y validada por el Grupo de trabajo de Atención Farmacéutica al Paciente con Enfermedad Infecciosa de la Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria. La metódica de evaluación consideró cada una de las dimensiones que conforman la prescripción del antimicrobiano e incluyó un algoritmo para calificar la prescripción global como adecuada, mejorable, inadecuada y no valorable.

ResultadosParticiparon 103 hospitales y se revisó el tratamiento de 3.568 pacientes, de los que 1.498 (42,0%) recibieron terapia antimicrobiana, 424 (28,3%) en combinación. La prevalencia de los antimicrobianos más frecuentes fue: amoxicilina-clavulánico 7,2%, ceftriaxona 6,4%, piperacilina-tazobactam 5,8% y meropenem 4,0%. Respecto a la adecuación del tratamiento la prescripción, fue considerada adecuada en el 34% de los casos, mejorable en el 45%, inadecuada en el 19% y no valorable en el 2%. Las dimensiones que más influyeron en la calificación de la prescripción como mejorable fueron el registro en la historia clínica, la elección del agente, la duración del tratamiento y la monitorización de la eficacia y seguridad, y como inadecuada la indicación de antimicrobiano.

ConclusionesLa metódica utilizada permite conocer la prevalencia y adecuación del uso de antimicrobianos, paso previo para diseñar y emprender acciones de mejora y medir el impacto de su implantación en el marco de los programas de optimización del uso de antimicrobianos.

Inappropriate use of antimicrobials is, to a greater or lesser extent, an undeniable reality in any hospital. However, the degree to which such drugs are inappropriately used is difficult to quantify due to the methodological and practical difficulties inherent in its measurements and the lack of standardized evaluation methods. Various studies in different countries have estimated inappropriate use of antimicrobials in hospitals at levels ranging between 16 and 70%1–4. The consequences of the inappropriate use of antimicrobials include an increased risk of adverse events such as Clostridioides difficile infection, therapeutic failure with potential effects on morbidity and mortality, selection of resistant microorganisms, and increased health costs5–7.

A particularly relevant phenomenon is the increase observed in bacterial resistance to antimicrobials, which has become a global health problem. The World Health Organization has set the antimicrobial stewardship as one of the five strategic goals in the fight against microbial resistance8.

Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) are being progressively implemented in Spanish hospitals. Their goals include improving clinical outcomes, minimizing adverse events, including resistance, and measuring and improving the appropriate use of antimicrobial agents to ensure the cost-effectiveness of treatments9,10.

Various strategies have been proposed to estimate the quality of antimicrobial use in different settings. One of them consists in establishing quality of use indicators based on consumption11,12. However, the most commonly used method for assessing the prevalence and use of antimicrobials is the performance of cross-sectional studies1,13,14. These are usually carried out in a single day and are an efficient tool when time and resources do not allow for a longitudinal study. A significant sample can provide information on the prescription of antibiotics at different times in the course of treatment. In Spain, the National Epidemiological Surveillance Network (RENAVE) annually records the prevalence of antimicrobial use in hospitals15.

The evaluation of antimicrobial drug prescriptions should consider several items such as indication, spectrum, dosage, duration, efficacy and safety monitoring, and registration. The biggest problem about performing a systematic evaluation of antimicrobial prescription is the difficulties in using a standardized method due to the complexities inherent in the evaluation of each of these items. Another critical point is the fraction of subjectivity in the evaluation that leads to inter-observer variability16–18.

The aim of the PAUSATE study was to evaluate the prevalence and degree of appropriateness of antimicrobial use in Spanish hospitals by means of a pharmacist-led cross-sectional systematic review.

MethodsStudy designThis was a nationwide multicenter cross-sectional study that analyzed 10% of the patients admitted to the participating hospitals on one day in April 2021. This percentage was chosen to avoid an excessive workload in larger hospitals and to encourage mass participation. Participation in the study was voluntary and channeled through the mailing list of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacists (SEFH). Each hospital was required to nominate a research pharmacist. Optionally, other pharmacists could also participate to help with data collection, but the actual evaluations were the responsibility of the research pharmacist.

The research pharmacist at each center chose a day within the study period to perform the prevalence cutoff. The study population was chosen by randomly selecting 10% of the patients admitted on the cutoff day, without excluding any clinical services. The randomization method was freely chosen by each hospital, although instructions were provided to do this using an Excel spreadsheet.

The study sample drawn from randomized patients and consisted of individuals receiving at least one antimicrobial on the day of the cutoff. The agents belonging to the following groups under the Anatomical, Therapeutic and Chemical Classification System (ATC)19: J01 (systemic antibacterials), J02 (systemic antifungal agents), J04 (antimycobacterials), J05AB (directacting nucleotide/nucleoside analogs, excluding reverse transcriptase inhibitors), J05AD (direct acting phosphonic acid derivative antivirals) and J05AH (direct acting neuraminidase inhibitor antivirals).

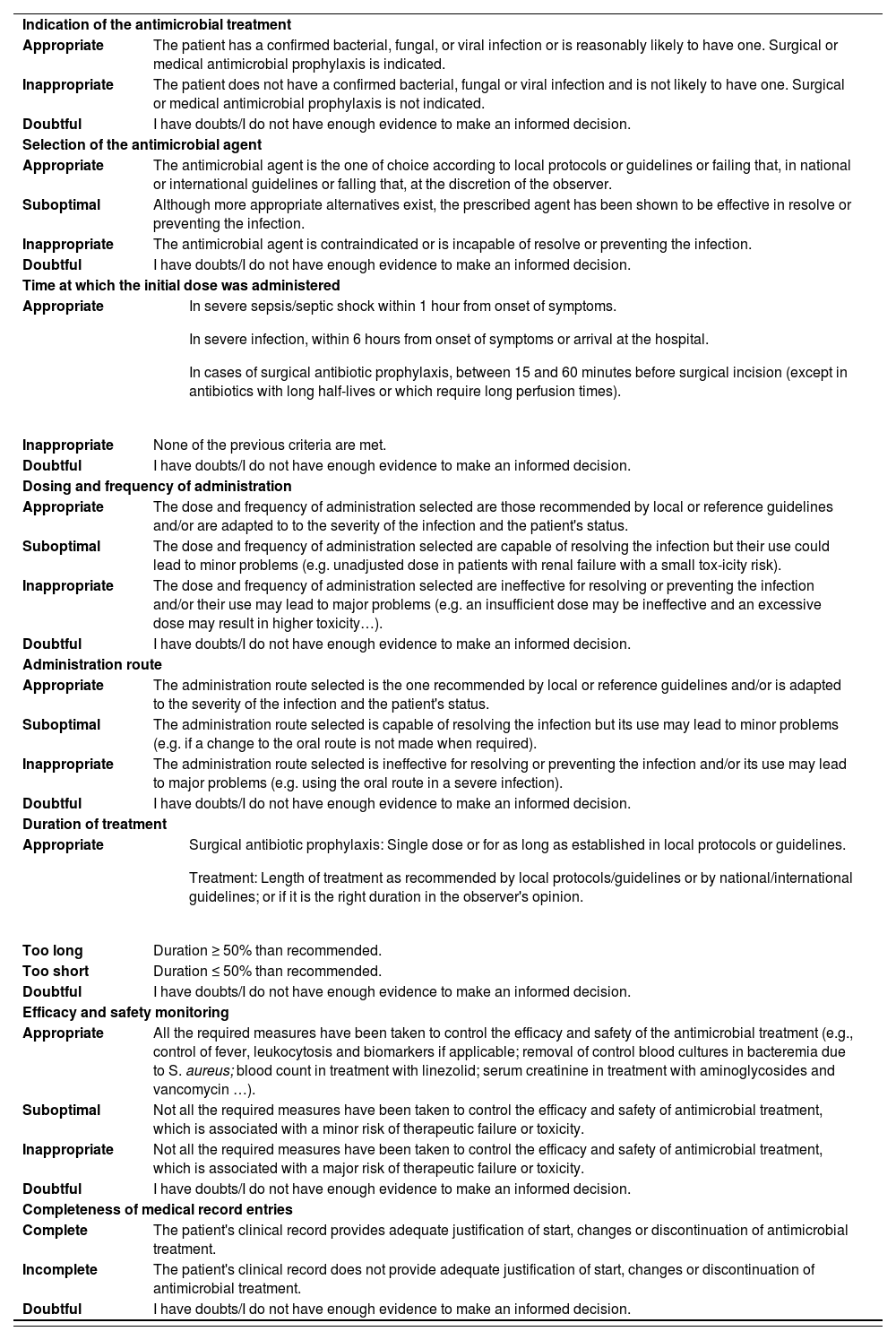

For every case, the research pharmacist evaluated and recorded the appropriateness of antimicrobial treatment following a methodology proposed and validated by the members of the coordinating committee of the SEFH's AFinf Working Group (Pharmaceutical Care of Patients with Infectious Diseases)20 (Table 1), and derived from on a series of indicators of hospital-based antimicrobial quality described in the literature21,22.

AFinf method of prescription evaluation

| Indication of the antimicrobial treatment | |

| Appropriate | The patient has a confirmed bacterial, fungal, or viral infection or is reasonably likely to have one. Surgical or medical antimicrobial prophylaxis is indicated. |

| Inappropriate | The patient does not have a confirmed bacterial, fungal or viral infection and is not likely to have one. Surgical or medical antimicrobial prophylaxis is not indicated. |

| Doubtful | I have doubts/I do not have enough evidence to make an informed decision. |

| Selection of the antimicrobial agent | |

| Appropriate | The antimicrobial agent is the one of choice according to local protocols or guidelines or failing that, in national or international guidelines or falling that, at the discretion of the observer. |

| Suboptimal | Although more appropriate alternatives exist, the prescribed agent has been shown to be effective in resolve or preventing the infection. |

| Inappropriate | The antimicrobial agent is contraindicated or is incapable of resolve or preventing the infection. |

| Doubtful | I have doubts/I do not have enough evidence to make an informed decision. |

| Time at which the initial dose was administered | |

| Appropriate |

|

| Inappropriate | None of the previous criteria are met. |

| Doubtful | I have doubts/I do not have enough evidence to make an informed decision. |

| Dosing and frequency of administration | |

| Appropriate | The dose and frequency of administration selected are those recommended by local or reference guidelines and/or are adapted to to the severity of the infection and the patient's status. |

| Suboptimal | The dose and frequency of administration selected are capable of resolving the infection but their use could lead to minor problems (e.g. unadjusted dose in patients with renal failure with a small tox-icity risk). |

| Inappropriate | The dose and frequency of administration selected are ineffective for resolving or preventing the infection and/or their use may lead to major problems (e.g. an insufficient dose may be ineffective and an excessive dose may result in higher toxicity…). |

| Doubtful | I have doubts/I do not have enough evidence to make an informed decision. |

| Administration route | |

| Appropriate | The administration route selected is the one recommended by local or reference guidelines and/or is adapted to the severity of the infection and the patient's status. |

| Suboptimal | The administration route selected is capable of resolving the infection but its use may lead to minor problems (e.g. if a change to the oral route is not made when required). |

| Inappropriate | The administration route selected is ineffective for resolving or preventing the infection and/or its use may lead to major problems (e.g. using the oral route in a severe infection). |

| Doubtful | I have doubts/I do not have enough evidence to make an informed decision. |

| Duration of treatment | |

| Appropriate |

|

| Too long | Duration ≥ 50% than recommended. |

| Too short | Duration ≤ 50% than recommended. |

| Doubtful | I have doubts/I do not have enough evidence to make an informed decision. |

| Efficacy and safety monitoring | |

| Appropriate | All the required measures have been taken to control the efficacy and safety of the antimicrobial treatment (e.g., control of fever, leukocytosis and biomarkers if applicable; removal of control blood cultures in bacteremia due to S. aureus; blood count in treatment with linezolid; serum creatinine in treatment with aminoglycosides and vancomycin …). |

| Suboptimal | Not all the required measures have been taken to control the efficacy and safety of antimicrobial treatment, which is associated with a minor risk of therapeutic failure or toxicity. |

| Inappropriate | Not all the required measures have been taken to control the efficacy and safety of antimicrobial treatment, which is associated with a major risk of therapeutic failure or toxicity. |

| Doubtful | I have doubts/I do not have enough evidence to make an informed decision. |

| Completeness of medical record entries | |

| Complete | The patient's clinical record provides adequate justification of start, changes or discontinuation of antimicrobial treatment. |

| Incomplete | The patient's clinical record does not provide adequate justification of start, changes or discontinuation of antimicrobial treatment. |

| Doubtful | I have doubts/I do not have enough evidence to make an informed decision. |

AFinf: Pharmaceutical Care of Patients with Infectious Diseases.

Each antimicrobial prescription was evaluated by filling in a form that included the items of indications of antimicrobial treatment, antimicrobial agents selected, time of administration of the first dose, dose and frequency of administration, route of administration, duration of treatment, monitoring of efficacy and adverse effects, and completeness of medical record entries. Each item was scored by the research pharmacist of each hospital according to the guidelines provided in table 1.

The evaluation was performed cross-sectionally, rather than longitudinally, in all items except for the duration of treatment, where a retrospective assessment was made once the antimicrobial treatment has been completed. A specific point was made to carry out the evaluation on the same day as the cut-off and, failing that, on the days immediately following, so that the evaluator would have the same clinical and microbiological information as the prescriber.

Prescription assessment criteriaOverall, prescriptions were considered appropriate if they were assessed as appropriate across all items (medical records fully completed); suboptimal if they were considered appropriate or suboptimal across all items (adequate or too long in duration of treatment and it did not affect if medical record entries were complete or incomplete); and inappropriate if it was so assessed in any item (too short in duration of treatment). If a prescription contained two doubtful items or less, this did not alter its assessment as appropriate, suboptimal or inappropriate, except if the indication for antibiotic therapy and the choice of agent were both doubtful, in which case it was considered unevaluable. If they received three or more doubtful ratings, they were assessed as unevaluable, except for prescriptions assessed as inappropriate (too short in duration of treatment), in which case they were considered inappropriate.

Data collectionData were obtained from the patient's medical records and, if necessary, by contacting the prescribing physician.

The variables collected for each participating center were: number of beds, patient census on the cut-off day and number of patients selected who were prescribed at least one antimicrobial agent. The variables collected for each patient were sex, age, clinical unit in charge, and active antimicrobial agent(s). Prescriptions were evaluated according to the criteria in table 1 on a form designed for that purpose.

The data were collected and managed using the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools made available by SEFH23.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research into Medicines of Galicia (Promoter's Code: AFI-AMO-2019-01, Registration Code: 2019/258). The committee decided that patients need not be asked to provide their informed consent. The management of each participating center was prospectively informed about the study design and methodology and all of them agreed to participate. The principal investigators and collaborators were not remunerated for their work. Physicians were personally contacted once their prescribed antimicrobial treatment was reviewed when, in the investigator's view, their prescriptions appeared to have a negative impact on patients.

Statistical analysisThe data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v. 20. Simple descriptive statistics were used to analyze both the prevalence and appropriateness of antimicrobial treatment.

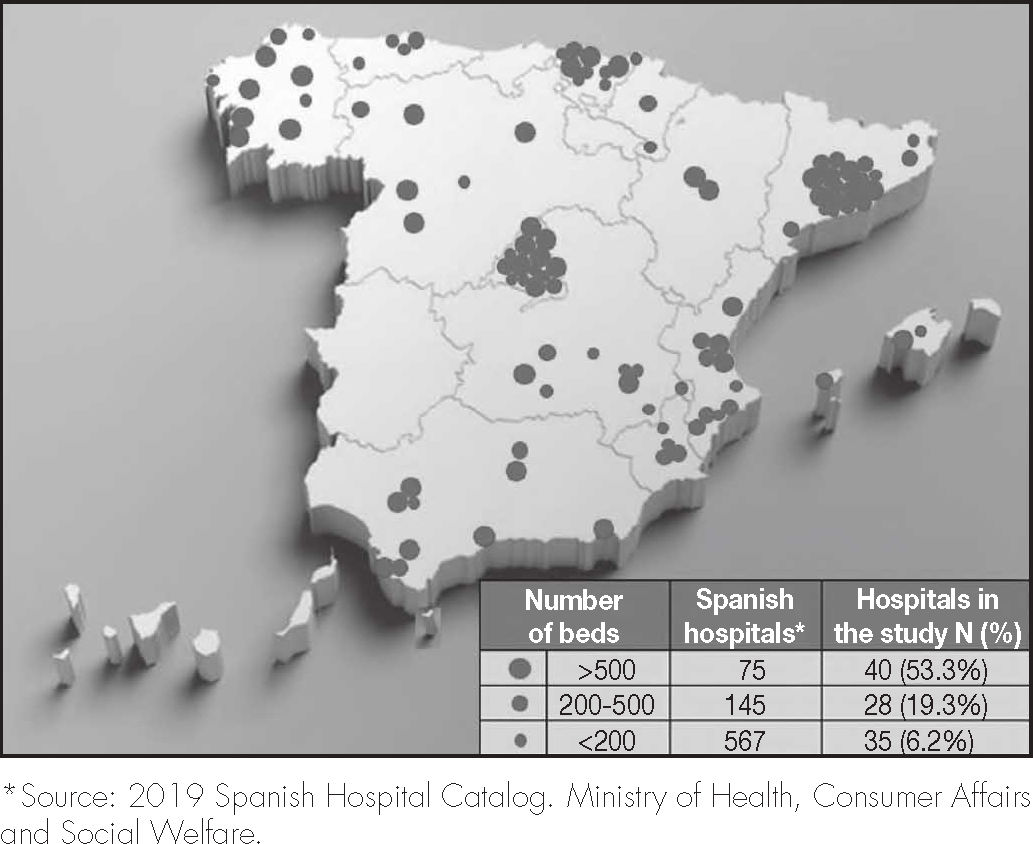

ResultsA total of 103 hospitals participated in the study, distributed heterogeneously throughout the Spanish territory. The composition by hospital size is reflected in figure 1, and shows a distribution that is not proportional to the real one, with a greater weight in the study of larger hospitals.

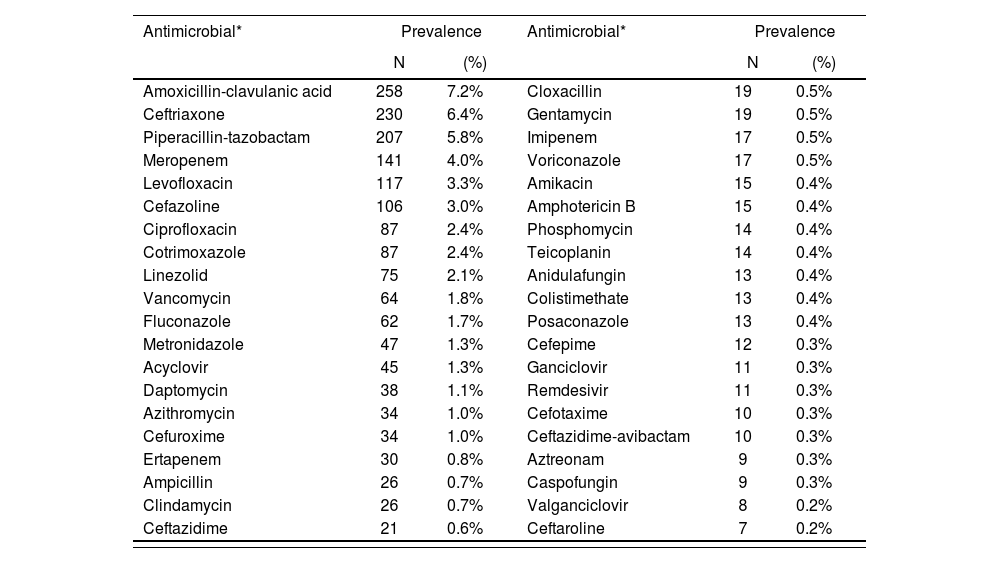

The prescriptions of 3,568 patients were reviewed, of whom 1,498 (42.0%) received antimicrobials. Of these, 862 (57.5%) were male and median age was 69 years (range: 0-101). A total of 46.6% of these patients were admitted to a medical unit, 31.2% to a surgical unit, 9.9% to a critical care unit, 8.4% to a hemato-oncological unit, 3.1% to a pediatric unit, and 0.8% to other units. Of the patients on antimicrobial therapy, 1,449 (96.7%) received at least one antibiotic, 126 (8.4%) at least one antifungal, and 80 (5.3%) at least one antiviral. The prevalence of the use of the most frequent antimicrobial agents is shown in table 2.

Prevalence of the use of the most commonly prescribed antimicrobials

| Antimicrobial* | Prevalence | Antimicrobial* | Prevalence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 258 | 7.2% | Cloxacillin | 19 | 0.5% |

| Ceftriaxone | 230 | 6.4% | Gentamycin | 19 | 0.5% |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 207 | 5.8% | Imipenem | 17 | 0.5% |

| Meropenem | 141 | 4.0% | Voriconazole | 17 | 0.5% |

| Levofloxacin | 117 | 3.3% | Amikacin | 15 | 0.4% |

| Cefazoline | 106 | 3.0% | Amphotericin B | 15 | 0.4% |

| Ciprofloxacin | 87 | 2.4% | Phosphomycin | 14 | 0.4% |

| Cotrimoxazole | 87 | 2.4% | Teicoplanin | 14 | 0.4% |

| Linezolid | 75 | 2.1% | Anidulafungin | 13 | 0.4% |

| Vancomycin | 64 | 1.8% | Colistimethate | 13 | 0.4% |

| Fluconazole | 62 | 1.7% | Posaconazole | 13 | 0.4% |

| Metronidazole | 47 | 1.3% | Cefepime | 12 | 0.3% |

| Acyclovir | 45 | 1.3% | Ganciclovir | 11 | 0.3% |

| Daptomycin | 38 | 1.1% | Remdesivir | 11 | 0.3% |

| Azithromycin | 34 | 1.0% | Cefotaxime | 10 | 0.3% |

| Cefuroxime | 34 | 1.0% | Ceftazidime-avibactam | 10 | 0.3% |

| Ertapenem | 30 | 0.8% | Aztreonam | 9 | 0.3% |

| Ampicillin | 26 | 0.7% | Caspofungin | 9 | 0.3% |

| Clindamycin | 26 | 0.7% | Valganciclovir | 8 | 0.2% |

| Ceftazidime | 21 | 0.6% | Ceftaroline | 7 | 0.2% |

Of the patients who received antimicrobial therapy, 424 (28.3%) did so in combination therapy; 358 (23.9%) received at least two antibiotics and 120 patients (8.0%) were treated with a combination of a β-lactam active against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and an agent active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

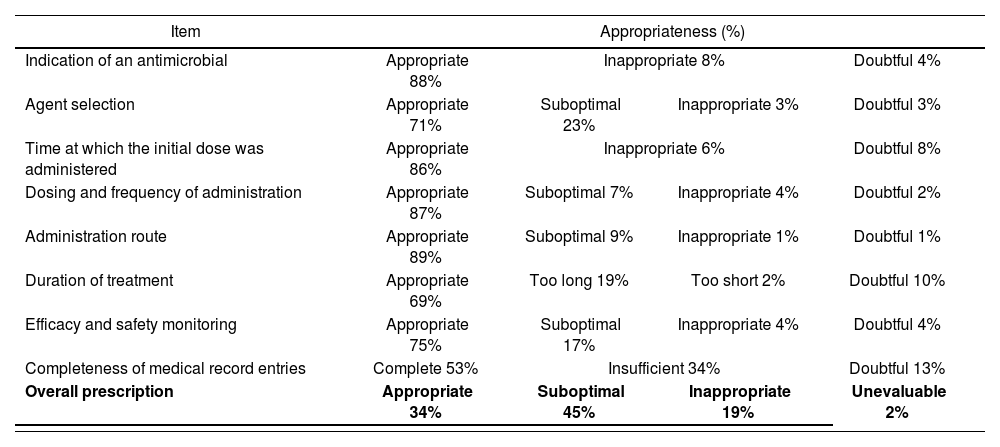

Regarding the appropriateness of treatment, the prescription was considered appropriate in 34% of the cases, suboptimal in 45%, inappropriate in 19% and unevaluable in 2% (Table 3).

Appropriateness by item and overall prescription

| Item | Appropriateness (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication of an antimicrobial | Appropriate 88% | Inappropriate 8% | Doubtful 4% | |

| Agent selection | Appropriate 71% | Suboptimal 23% | Inappropriate 3% | Doubtful 3% |

| Time at which the initial dose was administered | Appropriate 86% | Inappropriate 6% | Doubtful 8% | |

| Dosing and frequency of administration | Appropriate 87% | Suboptimal 7% | Inappropriate 4% | Doubtful 2% |

| Administration route | Appropriate 89% | Suboptimal 9% | Inappropriate 1% | Doubtful 1% |

| Duration of treatment | Appropriate 69% | Too long 19% | Too short 2% | Doubtful 10% |

| Efficacy and safety monitoring | Appropriate 75% | Suboptimal 17% | Inappropriate 4% | Doubtful 4% |

| Completeness of medical record entries | Complete 53% | Insufficient 34% | Doubtful 13% | |

| Overall prescription | Appropriate 34% | Suboptimal 45% | Inappropriate 19% | Unevaluable 2% |

The items that most influenced assess a prescription as suboptimal were completeness of medical record entries, type of antimicrobial agent selected, duration of treatment and monitoring of efficacy and safety. In 21% of cases where the prescription was assessed as suboptimal, the only reason was incompleteness of data in the patient's medical record (in 79% of the remaining cases, several items converged). The item that most influenced rating a prescription as inappropriate was the indication of antimicrobial treatment, with the antimicrobial being considered unnecessary in 8% of prescriptions.

DiscussionPAUSATE is the first nationwide study in Spain to simultaneously measure the prevalence and appropriateness of the hospital use of antimicrobials by means of a prevalence survey.

The prevalence data obtained in the PAUSATE study are similar to those in the latest RENAVE survey in 201915. Thus, in the PAUSATE study 42% of the patients were receiving at least one antimicrobial, as compared to 45.8% in the RENAVE survey. It should be considered, however, that both studies differ in the composition of the ATC groups analyzed. Indeed, the RENAVE study, unlike the PAUSATE study, included ATC groups A07 and P01 and excluded groups J04 (except for agents used for non-tuberculous bacteria) and J05, although these groups include agents with a small impact on consumption (the prevalence of each group is less than 2.5%). In the PAUSATE study, 28.3% of patients who received antimicrobials did so in combination therapy, as compared to 27.7% in the RENAVE survey.

Of the 10 most highly consumed antimicrobials in the PAUSATE study, nine were the same as in the RENAVE survey, with virtually identical positions. However, the use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials such as piperacillin-tazobactam, meropenem and linezolid was slightly higher in the PAUSATE study than in the RENAVE survey (5.8%, 4.0% and 2.1% vs. 5.2%, 3.5% and 1.8% respectively). Other antimicrobials such as amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, levofloxacin, cefazolin, and ciprofloxacin were more commonly used in the RENAVE survey than in the PAUSATE study (8.9%, 4.9%, 4.6% and 2.9% vs. 7.2%, 3.3%, 3.0% and 2.4%, respectively), which is consistent with the greater proportion of larger hospitals included in the PAUSATE study. Such hospitals tend to treat cases of greater complexity and usually exhibit higher incidences of nosocomial infections and resistant microorganisms.

Other findings resulting from the higher proportion of larger hospitals in the PAUSATE study include a higher prevalence of antifungals as compared to RENAVE (8.4% vs. 3.7%) and a higher percentage of patients on a combination of a β-lactam active against Pseudomonas aeruginosa with an agent active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (8.0%).

Unlike the RENAVE survey, the PAUSATE study was limited to collecting data on the prevalence and appropriateness of the use of antimicrobials, without gathering information on the indication for antimicrobials (prophylaxis, empirical or targeted therapy, or community or nosocomial infection) or patient-related risk factors (comorbidities, immunosuppression, devices and implants, etc.).

The National Plan against Antibiotic Resistance (PRAN) of the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products describes the levels of consumption of antimicrobials in Spanish hospitals, expressed as the number of Defined Daily Doses per 1,000 inhabitants per day24. Although these values cannot be compared directly with the prevalence data of the PAUSATE study as both the methodology and the units of measurement used are different, it can be seen that four of the five most commonly consumed antibiotics in the PRAN coincide in those reported in the PAUSATE prevalence study.

The international literature reports that between 16% and 70% of antimicrobial treatments are inappropriate. However, most of the data comes from low-quality studies characterized by very heterogeneous designs and methodologies. In Spain, a few studies were published that reveal the high levels of inappropriateness antimicrobial use in the country's hospitals, but they are either single-center or refer to specific areas of hospitalization25–27.

The main problem with assessing the quality of antimicrobial use is that there is no standardized evaluation method that covers all the different items of antimicrobial prescribing and that defines the scale of each of these items and by extension the qualification of the prescription as a whole.

A further critical point in the evaluation of antimicrobial prescribing is inter-observer variability. Subjectivity in the evaluation of antimicrobial prescribing is a consequence of the uncertainties inherent in many cases in the approach to infectious disease and the management of antibiotic therapy.

In order to minimize these aspects in the PAUSATE study, the AFinf group designed a method based on an evaluation form with specific and objective records related to local guidelines or, in their absence, to national or international reference guidelines. The form was put together by a group of pharmacists with long experience in the care of patients with infectious diseases who, in many cases, were members of their hospitals’ antibiotic stewardship teams.

The PAUSATE study showed that 45% of antimicrobial prescriptions were suboptimal and 19% were inappropriate.

In the analysis by items, the one with the greatest room for improvement was completeness of medical record entries, with entries being incomplete in 34% of prescriptions. This item was not considered crucial enough to assess the whole prescription as inappropriate, but it was the reason why one out of every five prescriptions were assessed as suboptimal rather than appropriate.

Documenting the clinical management plan, as well as reflecting the antimicrobial treatment selected together with its indication and the duration of treatment are recommendations included in stewardship programs21,28. Explicitly stating an antibiotic plan in the patients’ medical record helps physicians reflect on the decisions made and facilitates the review of antibiotic treatment.

The choice of antimicrobial agent was suboptimal in 23% and inappropriate in 3% of the prescriptions evaluated. A suboptimal assessment indicated non-adherence to reference protocols or guidelines or the use of equally effective but less safe, ecological, or inexpensive therapeutic alternatives. An inappropriate assessment refers to a larger issue of ineffectiveness or safety of the prescribed agent.

Other items with less favorable results were the duration of treatment (excessive in 19% of cases and too short in 2%) and the monitoring of efficacy and safety (suboptimal in 17% of cases and inappropriate in 4%).

The most concerning result of the study was the considerable percentage of prescriptions classified as inappropriate (19%), i.e., those where, in the evaluator's opinion, the patient did not require an antimicrobial, or its use did not guarantee the patient's cure or caused unacceptable harm. This data reinforces the need to implement measures to optimize the use of antimicrobials.

This study presents with several limitations. Firstly, the voluntary participation of the centers, apart from providing a heterogeneous distribution that is not representative of reality, with a disproportionately high participation of larger hospitals, can lead to a selection bias as it could be argued that the centers participating in the study were those most keen on optimizing the use of antimicrobials. Another selection bias is that the study sample only included patients who received at least one antimicrobial, excluding those who did not receive an antimicrobial although they required it (default antimicrobial indications were not analyzed).

Another limitation of the study is seasonality. The use of antimicrobials varies between different times of the year. The PAUSATE study was carried out in the month of April and overlapped with the RENAVE survey, which collected its data in May. Another factor that could distort the data obtained on antimicrobial use is the presence of patients admitted with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. During the data collection period, the percentage of hospital beds occupied by patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection ranged between 6.4% and 8.2%29.

The fact that the study was conducted by hospital pharmacists could have constituted an observer bias. Evaluation of antimicrobial prescriptions is assumed to be subject to nuances dependent on the observer's judgment. The influence of the observer's academic background in his evaluation of antimicrobial prescriptions was not studied. A forthcoming study, to be published as an extension of the present one, will measure the concordance of assessments by pharmacists and physicians using the AFinf method.

In short, the PAUSATE study provides updated data on the prevalence of the use of antimicrobials in Spanish hospitals. The data obtained are consistent with those previously published in the RENAVE survey and those reported by the PRAN Plan. Moreover, the study is the first of its kind to evaluate appropriateness of antimicrobial use, contemplating all the items in antimicrobial prescribing. An understanding of the prevalence and appropriateness of antimicrobial use is the first step for designing and undertaking the measures required to improve and measuring the impact of implementing antimicrobials within the framework of antimicrobial stewardship plans.

FundingNo funding was received for this research. The authors and investigators, and their collaborators, received no remuneration for participating in this study.

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to thank the researchers and other professionals involved in the collection of the data. Their names are contained in a specific section.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have declared no conflict of interest with respect to this research.

Contribution to the scientific literaturePAUSATE is a nationwide study aimed at measuring the prevalence and appropriateness of antimicrobials use in hospitals.

The results of the study should subsequently be used to design actions geared towards improving antimicrobial stewardship programs.

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña | José María Gutiérrez Urbón |

| Hospital Público de Monforte de Lemos | Laura Villaverde Piñeiro |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo |

|

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense | Maria del Pilar Rodriguez Rodriguez |

| Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti |

|

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ferrol |

|

| Hospital Público da Mariña |

|

| Hospital Público Virxe da Xunqueira | José Luis Rodríguez Sánchez |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra |

|

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario Santiago de Compostela | María Teresa Rodríguez Jato |

| Hospital del Mar | Daniel Echeverría Esnal Santiago Grau Cerrato |

| Hospital San Agustín de Linares | María Rosa Cantudo Cuenca |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón |

|

| Hospital Vega Baja Orihuela |

|

| Hospital de Molina |

|

| Hospital Morales Meseguer |

|

| Hospital de Figueres | Virginia Gol Vallés |

| Hospital Universitari General de Catalunya | Maria Pilar Marcos Pascua |

| Hospital General Mancha Centro | Ma Carmen Conde García |

| Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real |

|

| Hospital universitari Son Espases | Leonor del Mar Periañez Parraga |

| Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes |

|

| Hospital de Barcelona | Ana Ayestarán |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre |

|

| Hospital Universitario Torrejón de Ardoz | Guadalupe Sevilla Santos |

| Hospital de Sant Joan de Déu | María Goretti López Ramos |

| Hospital Clínico de Salamanca |

|

| Sanatorio Sagrado Corazón de Valladolid | Antonio Martin González |

| Hospital Universitario Santa Cristina | Iratxe Marquínez Alonso |

| Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia |

|

| Hospital Fundació Esperit Sant | Núria Miserachs Aranda |

| Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge |

|

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete |

|

| Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe |

|

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío |

|

| Institut Catalá d'Oncologia Badalona |

|

| Hospital Torrecárdenas |

|

| Hospital Can Misses |

|

| Hospital QuironSalud Sagrado Corazón | Ángel Albacete Ramírez |

| Hospital Universitario de Jaén |

|

| Hospital Sagrat Cor Barcelona |

|

| Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León | Mónica Sáez Villafañe |

| Fundacion Hospital de Avilés | Paula Raviña Fernández |

| Hospital La Pedrera | Amparo Navarro Catalá |

| Hospital Universitario de La Ribera | Paula García Llopis |

| Hospital Universitario de Jerez |

|

| Hospital Clínico San Carlos |

|

| Hospital Universitario de Móstoles |

|

| Hospital de la Vega Lorenzo Guirao |

|

| Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía |

|

| Hospital Monte Naranco |

|

| Hospital Arnau de Vilanova-Lliria |

|

| Hospital Puerta de Hierro |

|

| Complejo Asistencial de Zamora |

|

| Complejo Hospitalario de Puerto Real |

|

| Hospital El Bierzo | Julio Antonio Valdueza Beneitez |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz | Francisco Moreno Ramos |

| Hospital de Hellín | Gregorio Romero Candel |

| Hospital General Universitario de Elche |

|

| Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol |

|

| Hospital Universitario Donostia | Miren Ercilla Liceaga |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet |

|

| Hospital Universitario de Igualada |

|

| Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias |

|

| Hospital QuirónSalud Albacete |

|

| Hospital Quirón Barcelona |

|

| Hospital General Universitario Castellón |

|

| Clínica IMQ Zorrotzaurre | Cristina Garay Sarría |

| Hospital Comarcal d'Inca | María Jaume Gaya |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria | Elena Sánchez Yáñez |

| Hospital Universitario Vall d'Hebron |

|

| Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena |

|

| Hospital Fremap de Majadahonda | Aixa Fernández Estalella |

| Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante |

|

| Hospital San Vicente del Raspeig |

|

| Hospital Universitario Mutua Terrassa | Núria Sanmartí Martínez |

| Hospital Virgen del Mar |

|

| Hospital Puerta del Mar | María Eugenia Rodríguez Mateos |

| Hospital Universitario de Burgos |

|

| Fundació Hospital Sant Joan de Déu de Martorell | Marta Martí Navarro |

| Hospital San Eloy | Jaione Bilbao Aguirregomezcorta |

| Clinica La Asunción | Borja Ollo Tejero |

| Hospital Universitario la Princesa |

|

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau |

|

| Hospital Universitario Basurto | José Antonio Domínguez Menéndez |

| Hospital Alto Deba |

|

| Hospital Urduliz | Eguzkiñe Ibarra García |

| Hospital Universitario Infanta Elena |

|

| Hospital General de Valdepeñas |

|

| Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa |

|

| Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII |

|

| Organización Sanitaria Integrada Bidasoa | Maria Idoia Michelena Hernández |

| Hospital Santa Marina | Joana González Arnáiz |

| Hospital Universitario Cruces |

|

| Hospital General de Villarrobledo |

|

| Hospital General de Almansa |

|

| Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina | Miguel Ángel Amor García |

| Hospital San Rafael |

|

| Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí | Sara Ortonobes Roig |

| Hospital Universitario Dr. Josep Trueta |

|

| Hospital Carmen y Severo Ochoa |

|

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra | Irene Aquerreta González |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Santa Cristina de Albacete |

|

Early Access date (08/02/2022).