To assess the degree of implementation of medication error prevention practices in Spanish hospitals.

MethodDescriptive multicenter study of the degree of implementation of the safety practices included in the “Medication use-system safety self-assessment for hospitals. Version. II”. Spanish hospitals that completed the questionnaire between October, 2021 and September, 2022 participated. The survey contains 265 items for evaluation grouped into 10 key elements. Mean score and mean percentages based on the maximum possible values for the overall survey, for the key elements, and for each individual item of evaluation were calculated. The results were compared with those of the previous 2011 study.

ResultsA total of 131 hospitals from 15 autonomous regions participated in the study. The mean score of the overall questionnaire in all hospitals was 898.2 (57.4% of the maximum possible score). No differences were found according to dependency, size, or type of hospital, either in the overall questionnaire or in the key elements. The lowest values were found for key elements VIII, I and VI, on competence and training of health professionals in safety practices (45.1%), availability and accessibility of essential information on patients (48%), and devices for administering drugs (52.3%). With respect to 2011, significant increases were found both in the overall questionnaire and in the key elements, except V and VII, referring to standardization, storage, and distribution of medications, and environmental factors and human resources. Several evaluation items on the safe management of high-risk drugs, medication reconciliation, incorporation of clinical pharmacists into the healthcare teams, and implementation of technologies that allow full traceability throughout the medication system, showed low percentages.

ConclusionsThere has been appreciable progress in the degree of implementation of some medication error prevention practices in Spanish hospitals, but many proven efficacy practices recommended by the World Health Organization and safety organizations are still poorly implemented. The information obtained can be useful for prioritizing the practices to be addressed and as a new baseline for monitoring progress.

Conocer el grado de implantación de las prácticas de prevención de errores de medicación en los hospitales españoles.

MétodoEstudio descriptivo multicéntrico del grado de implantación de las prácticas seguras recogidas en el “Cuestionario de autoevaluación de la seguridad del uso de los medicamentos en los hospitales. Versión II”. Participaron aquellos hospitales españoles que cumplimentaron este cuestionario entre Octubre/2021 y Septiembre/2022. El cuestionario contiene 265 ítems de evaluación agrupados en 10 elementos clave. Se calculó la puntuación media y el porcentaje medio sobre el valor máximo posible para el cuestionario completo, los elementos clave y los ítems de evaluación. Los resultados se compararon con los del estudio realizado en 2011.

ResultadosParticiparon 131 hospitales de 15 comunidades autónomas. La puntuación media del cuestionario completo en los hospitales fue de 898,2 (57,4% del valor máximo posible). No se encontraron diferencias según dependencia, tamaño o finalidad asistencial, ni en el cuestionario completo ni en los elementos clave. Presentaron los valores más bajos los elementos clave VIII, I y VI, sobre competencia y formación de los profesionales en prácticas seguras (45,1%), disponibilidad y accesibilidad de la información esencial sobre los pacientes (48%), y dispositivos para la administración de medicamentos (52,3%). Con respecto a 2011, se encontraron aumentos significativos tanto en el cuestionario completo como en los elementos clave, excepto en el V y VII, referentes a la estandarización, almacenamiento y distribución de medicamentos, y a los factores del entorno y recursos humanos. Diversos ítems de evaluación sobre manejo seguro de medicamentos de alto riesgo, conciliación de la medicación, incorporación de farmacéuticos clínicos a los equipos asistenciales e implantación de tecnologías que permiten una trazabilidad total en el circuito del medicamento, mostraron porcentajes bajos.

ConclusionesSe han producido avances apreciables en el grado de implantación de algunas prácticas de prevención de errores en los hospitales españoles, pero siguen estando escasamente implementadas numerosas prácticas de eficacia probada recomendadas por la Organización Mundial de la Salud y por organismos de seguridad. La información obtenida puede ser útil para priorizar las prácticas a abordar y como nueva línea basal para efectuar un seguimiento de los progresos.

Currently, medication errors remain a leading cause of preventable harm in healthcare systems around the world,1 even though the last 2 decades have seen considerable progress in knowledge about and implementation of strategies and safety practices to prevent them.2 According to a recent report,3 within member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), as many as 1 in 10 hospital admissions is caused by an adverse event related to medications, and as many as 1 in 5 patients suffer harm associated with medications during their hospital stay, globally all at a cost of 54 billion dollars in OECD countries.

Improving medication safety in hospitals requires the implementation of multiple safety practices in each and every stage of the medication use system, given their extraordinary amplitude and complexity. The approach must be multidisciplinary and must include all healthcare professionals involved in medication use. In order to achieve improvements, numerous organizations have recommended that a multidisciplinary team at each hospital periodically use a proactive self-assessment tool to evaluate safety in the medication use system and identify risks and opportunities for improvement, with such information being applied toward prioritizing and planning safety practices to be implemented.4–6

To this end, in 2007, the Ministry of Health published the “Medication Use-System Safety Self-Assessment for Hospitals”,7 which is an adaptation to Spanish healthcare practice of the Medication Safety Self-Assessment for Hospitals, originally developed by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). Using this questionnaire, the Ministry of Health and ISMP-Spain, with collaboration from the autonomous regions in Spain and the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH), carried out 2 national studies, one in 2007 and another in 2011,8,9 that provided information about the implementation of medication safety practices in Spanish hospitals, information that was used to prioritize practices to be included in patient safety strategies at various levels.

In 2018, the Spanish survey was updated10 to reflect new best practices from updates made earlier in the United States, Australia, and Canada.11–13 Taking advantage of its availability, the SEFH Working Group of Clinical Safety decided to conduct a new study, which was supported by the Ministry of Health. The main objective of this study was to provide updated information on the implementation of safe medication practices in Spanish hospitals. An additional objective was to encourage proactive and comprehensive assessments of the medication use systems in Spanish hospitals performed by multidisciplinary teams at each institution.

MethodsDescriptive multicenter study of the degree of implementation of the safety practices included in the “Medication Use-System Safety Self-Assessment for Hospitals. Version. II”.10 Participants in the study were Spanish hospitals that completed the questionnaire between October, 2021 and September, 2022. The survey was disseminated by the SEFH using its mailing list for members and by the Ministry of Health contacting those responsible for quality assurance in the autonomous regions. Questionnaire responses were recorded using a web-based program found on the ISMP-Spain website that guarantees confidentiality.

Questionnaire and scoringThe second version of the “Medication Use-System Safety Self-Assessment for Hospitals” consists of 265 evaluation items that are designed to reflect specific practices or measures used to prevent medication errors.10 The items are organized into 10 sections which correspond to the 10 key elements that, according to the ISMP conceptual model, determine the safety of the medication use system, which in turn include one or more core characteristics.

The self-assessment should be carried out in several sessions by a multidisciplinary team that is knowledgeable about the procedures for the use of medications in different areas of the hospital. This team should assess the degree of implementation of each evaluation item by choosing 1 of the following 5 possible responses provided:

- a.

There have been no initiatives taken to implement this item.

- b.

This item was discussed for possible implementation, but has not been implemented.

- c.

This item has been partially implemented in some or all areas, patients, medications, or healthcare professionals.

- d.

This item has been completely implemented in some areas, patients, medications, or healthcare professionals.

- e.

This item has been completely implemented in all areas, patients, medications, or healthcare professionals.

The evaluation items are assigned different numerical values depending on their efficacy for preventing medication errors and their impact on the safety of the system as a whole. Option A always has a value of 0, while the numerical values for options B, C, D, and E increase progressively to a maximum value for option E that ranges from 2 to 16 points. In addition, the questionnaire has a total of 27 items that accept a response of “not applicable” for situations in which the hospital does not perform the activity referred to in the item (i. e., if the hospital doesn’t treat pediatric patients or if it doesn’t prepare antineoplastics). The possible points for these items are subtracted from the overall count if they are responded to as “not applicable”.

The members of the teams were not provided with the numerical values of the items during the evaluation stage, but instead, once the assessment was finished, those responsible for it at each hospital entered the responses onto the computer application for the assessment, and obtained final scoring for each evaluation item.

The aggregate analysis of the results for the participating hospitals included the calculation of mean scores in absolute value obtained for the complete questionnaire, for each key element, and also for each one of the 265 evaluation items. Moreover, percentages based on the maximum possible values were calculated, since these percentages allow for comparison among the key elements or evaluation items, since the maximum possible score for each of them is different. This mean percentage would range from 0% (which would indicate 0 implementation of the key element or evaluation item) to 100% (complete implementation).

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the characteristics of the hospitals participating in the study was performed and the scores and percentages on the maximum possible scores achieved for the entire questionnaire and for the key elements were compared among the hospitals in the sample, stratified according to their characteristics. The variables considered were: (1) functional dependence, with the categories of public and private hospitals; (2) number of beds, with the following categories: <200 beds, 200–499 beds, and ≥500 beds; and (3) type of hospital, which was categorized as general hospital, and monographic or other hospitals.

In order to determine whether or not any statistically significant changes had occurred in terms of the implementation of safe medication practices in hospitals between the year 2011 and 2022, we compared the values from both studies as expressed in percentages on the maximum possible scores for the entire questionnaire and for the key elements.

The statistical tests used were the Student's t-test for the comparison of means in 2 independent samples, or the analysis of variance for more than 2 samples; in the case of non-homogeneous variances, the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were used, respectively. The level of statistical significance was p < .05.

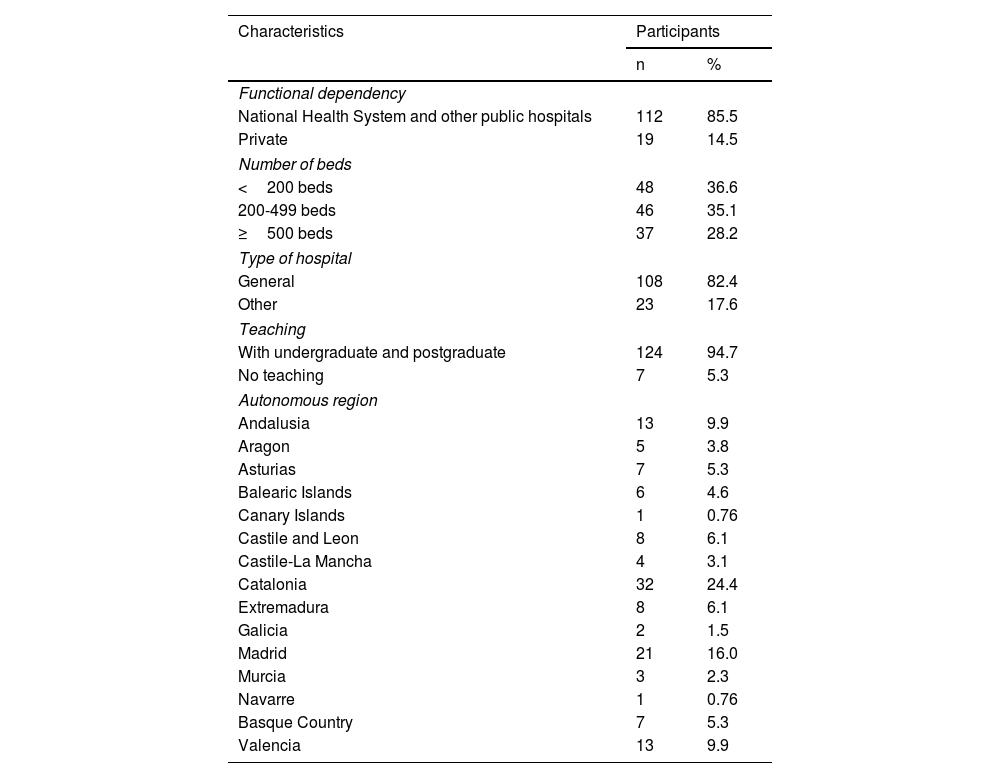

ResultsThere were 131 hospitals from 15 autonomous regions that participated in the study, of which 112 were public and 19 private, and whose characteristics can be found in Table 1. Of these, 36.6% were hospitals with <200 beds, 35.1% with 200–499 beds, and 28.2% with ≥500 beds. With respect to type of hospital, 108 were general hospitals and 23 monographic hospitals.

Characteristics of the hospitals that participated in the study (n = 131).

| Characteristics | Participants | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Functional dependency | ||

| National Health System and other public hospitals | 112 | 85.5 |

| Private | 19 | 14.5 |

| Number of beds | ||

| <200 beds | 48 | 36.6 |

| 200-499 beds | 46 | 35.1 |

| ≥500 beds | 37 | 28.2 |

| Type of hospital | ||

| General | 108 | 82.4 |

| Other | 23 | 17.6 |

| Teaching | ||

| With undergraduate and postgraduate | 124 | 94.7 |

| No teaching | 7 | 5.3 |

| Autonomous region | ||

| Andalusia | 13 | 9.9 |

| Aragon | 5 | 3.8 |

| Asturias | 7 | 5.3 |

| Balearic Islands | 6 | 4.6 |

| Canary Islands | 1 | 0.76 |

| Castile and Leon | 8 | 6.1 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 4 | 3.1 |

| Catalonia | 32 | 24.4 |

| Extremadura | 8 | 6.1 |

| Galicia | 2 | 1.5 |

| Madrid | 21 | 16.0 |

| Murcia | 3 | 2.3 |

| Navarre | 1 | 0.76 |

| Basque Country | 7 | 5.3 |

| Valencia | 13 | 9.9 |

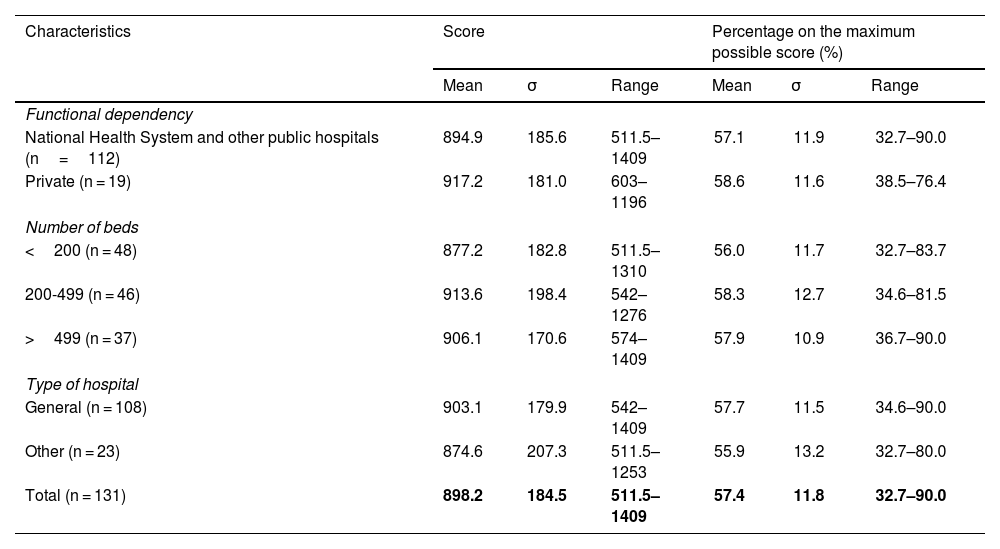

Table 2 shows the overall results obtained for the questionnaire in the 131 hospitals and in the different groups established according to functional dependency, size, and type of hospital. The mean score for the complete questionnaire in all of the hospitals was 898.2 which is 57.4% of the total maximum score (1566). There was a broad range in the results obtained among the sample hospitals, ranging from 511.5 to 1409. There were no significant statistical differences among the percentages on the maximum possible scores obtained among the different groups of hospitals.

Results for the complete questionnaire according to the characteristics of the hospitals (n = 131).

| Characteristics | Score | Percentage on the maximum possible score (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | σ | Range | Mean | σ | Range | |

| Functional dependency | ||||||

| National Health System and other public hospitals (n=112) | 894.9 | 185.6 | 511.5–1409 | 57.1 | 11.9 | 32.7–90.0 |

| Private (n = 19) | 917.2 | 181.0 | 603–1196 | 58.6 | 11.6 | 38.5–76.4 |

| Number of beds | ||||||

| <200 (n = 48) | 877.2 | 182.8 | 511.5–1310 | 56.0 | 11.7 | 32.7–83.7 |

| 200-499 (n = 46) | 913.6 | 198.4 | 542–1276 | 58.3 | 12.7 | 34.6–81.5 |

| >499 (n = 37) | 906.1 | 170.6 | 574–1409 | 57.9 | 10.9 | 36.7–90.0 |

| Type of hospital | ||||||

| General (n = 108) | 903.1 | 179.9 | 542–1409 | 57.7 | 11.5 | 34.6–90.0 |

| Other (n = 23) | 874.6 | 207.3 | 511.5–1253 | 55.9 | 13.2 | 32.7–80.0 |

| Total (n = 131) | 898.2 | 184.5 | 511.5–1409 | 57.4 | 11.8 | 32.7–90.0 |

σ: standard deviation.

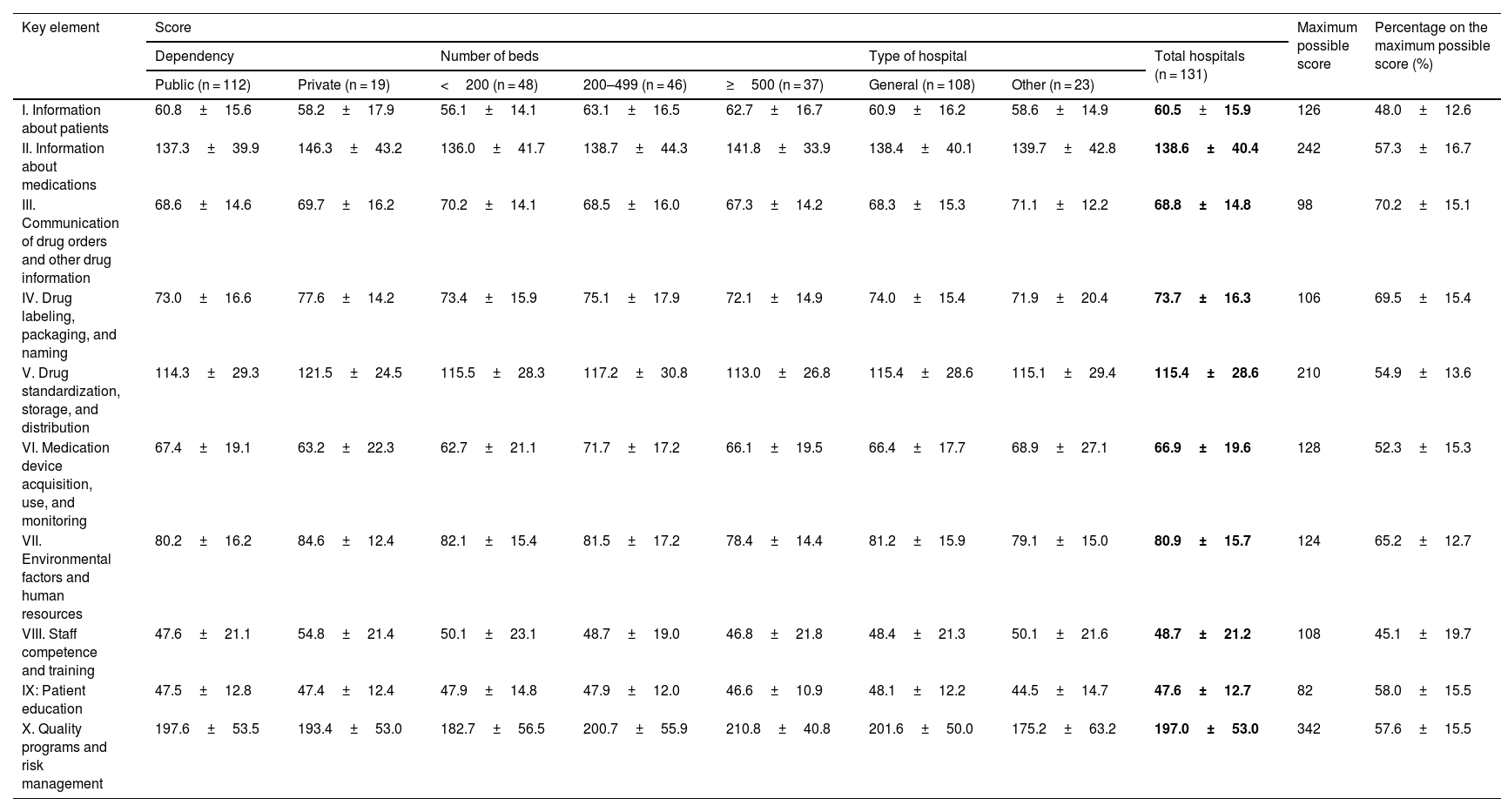

Table 3 shows the mean scores obtained for the 10 key elements in the totality of the hospitals and in the groups considered according to dependency, size, and type of hospital. It also shows the results expressed as a percentage on the maximum possible score for the key elements, which allows for making comparisons and determining those areas where there are more opportunities for improvement. No statistically significant differences were found between the results obtained in the different categories of hospitals. The lowest values were found for key elements VIII, I, and VI, on competence and training of healthcare professionals in safety practices (45.1%), availability and accessibility of essential information on patients (48%), and acquisition and use of devices for administering drugs (52.3%). Four other elements showed percentages between 50% and 60%: element V (54.9%) on drug standardization, storage, and distribution; II (57.3%) on availability of information about medications; X (57.6%) on quality and risk management programs; and IX (58%) on patient education.

Results obtained for the key elements as scores (mean±standard deviation) according to the characteristics of the hospitals and as a percentage on the maximum possible score for all hospitals (n = 131).

| Key element | Score | Maximum possible score | Percentage on the maximum possible score (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependency | Number of beds | Type of hospital | Total hospitals (n = 131) | |||||||

| Public (n = 112) | Private (n = 19) | <200 (n = 48) | 200–499 (n = 46) | ≥500 (n = 37) | General (n = 108) | Other (n = 23) | ||||

| I. Information about patients | 60.8±15.6 | 58.2±17.9 | 56.1±14.1 | 63.1±16.5 | 62.7±16.7 | 60.9±16.2 | 58.6±14.9 | 60.5±15.9 | 126 | 48.0±12.6 |

| II. Information about medications | 137.3±39.9 | 146.3±43.2 | 136.0±41.7 | 138.7±44.3 | 141.8±33.9 | 138.4±40.1 | 139.7±42.8 | 138.6±40.4 | 242 | 57.3±16.7 |

| III. Communication of drug orders and other drug information | 68.6±14.6 | 69.7±16.2 | 70.2±14.1 | 68.5±16.0 | 67.3±14.2 | 68.3±15.3 | 71.1±12.2 | 68.8±14.8 | 98 | 70.2±15.1 |

| IV. Drug labeling, packaging, and naming | 73.0±16.6 | 77.6±14.2 | 73.4±15.9 | 75.1±17.9 | 72.1±14.9 | 74.0±15.4 | 71.9±20.4 | 73.7±16.3 | 106 | 69.5±15.4 |

| V. Drug standardization, storage, and distribution | 114.3±29.3 | 121.5±24.5 | 115.5±28.3 | 117.2±30.8 | 113.0±26.8 | 115.4±28.6 | 115.1±29.4 | 115.4±28.6 | 210 | 54.9±13.6 |

| VI. Medication device acquisition, use, and monitoring | 67.4±19.1 | 63.2±22.3 | 62.7±21.1 | 71.7±17.2 | 66.1±19.5 | 66.4±17.7 | 68.9±27.1 | 66.9±19.6 | 128 | 52.3±15.3 |

| VII. Environmental factors and human resources | 80.2±16.2 | 84.6±12.4 | 82.1±15.4 | 81.5±17.2 | 78.4±14.4 | 81.2±15.9 | 79.1±15.0 | 80.9±15.7 | 124 | 65.2±12.7 |

| VIII. Staff competence and training | 47.6±21.1 | 54.8±21.4 | 50.1±23.1 | 48.7±19.0 | 46.8±21.8 | 48.4±21.3 | 50.1±21.6 | 48.7±21.2 | 108 | 45.1±19.7 |

| IX: Patient education | 47.5±12.8 | 47.4±12.4 | 47.9±14.8 | 47.9±12.0 | 46.6±10.9 | 48.1±12.2 | 44.5±14.7 | 47.6±12.7 | 82 | 58.0±15.5 |

| X. Quality programs and risk management | 197.6±53.5 | 193.4±53.0 | 182.7±56.5 | 200.7±55.9 | 210.8±40.8 | 201.6±50.0 | 175.2±63.2 | 197.0±53.0 | 342 | 57.6±15.5 |

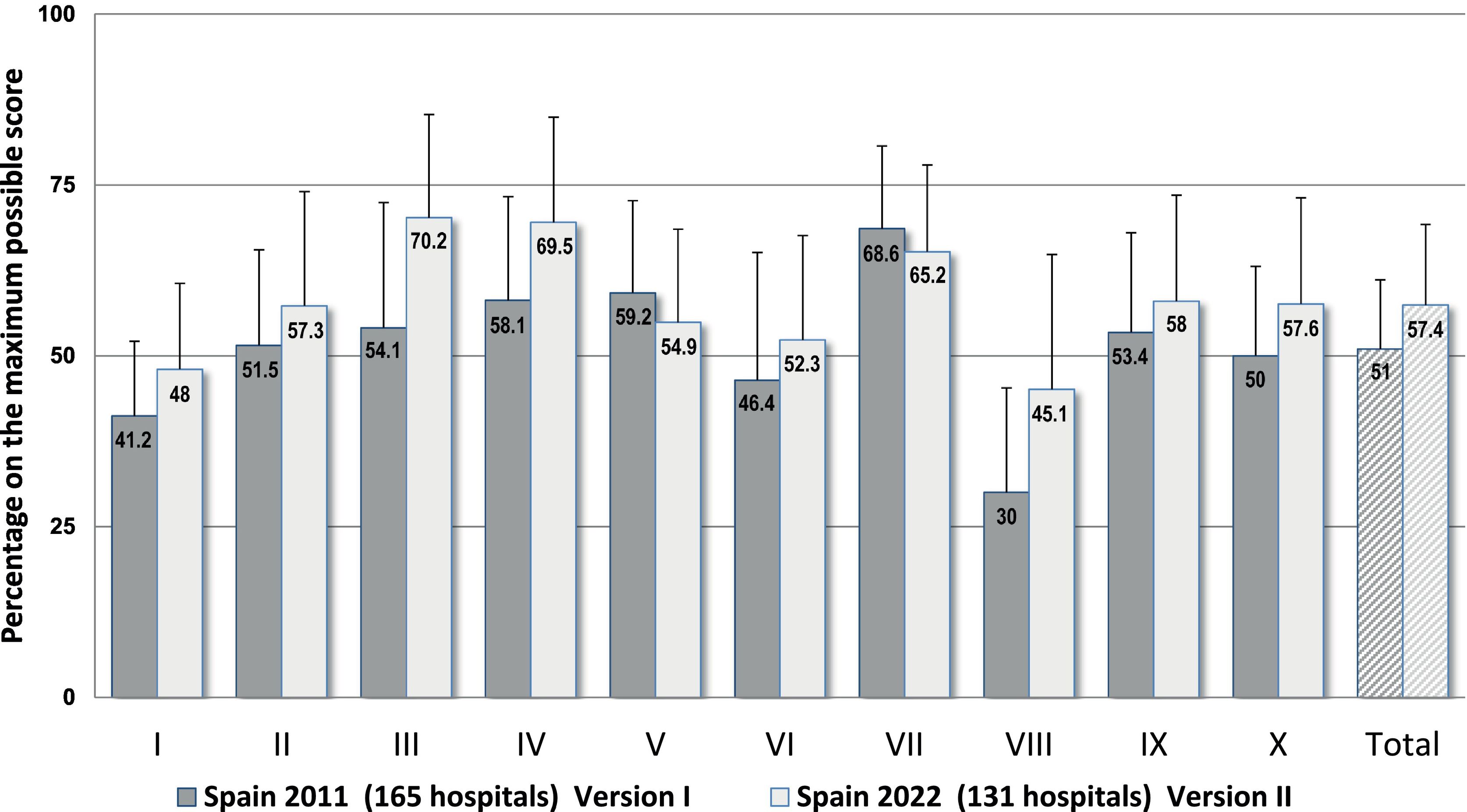

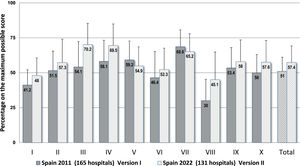

Fig. 1 is a graphic representation of the results found for the key elements and for the complete questionnaire in the current study and in the study carried out in 2011, which used Version I and included 165 hospitals. A statistically significant increase of 7.7% was observed in the percentages for the complete questionnaire in 2022 as opposed to 2011, as well as differences in all of the key elements. Although the current Version II uses a tougher scoring for some items and also incorporates several new items, the scores observed for 8 key elements in 2022 were higher than those in 2011, which, indeed, reflects greater implementation of safety practices, especially in key element III (+18.9%) on communication about prescriptions and other types of medication information, for element VIII (+15.3%) on healthcare professionals’ competence and training in safety practices, and for element IV (+12.6%) on drug labeling, packaging, and naming. However, lower scores were observed for key elements VII (−3.3%) and V (−3.2%), on environmental factors and human resources, and on drug standardization, storing, and distribution, respectively, since Version II includes some new items which earned low scores. These refer to the centralized preparation of intravenous mixtures in the pharmacy service and the control of automated dispensing systems, as well as the provision of trained personnel for handling and maintaining new technologies, and of pharmacists for specialized areas of work.

Results obtained for the 10 key elements and for the complete questionnaire expressed as percentages on the maximum possible scores in this study (n = 131 hospitals) and in the previous 2011 national study using Version I of the questionnaire (n = 165 hospitals).

Abbreviated description of the key elements: I. Availability and accessibility of patient information. II. Availability and accessibility of information about medications. III. Communication of drug orders and other types of medication information. IV. Drug labeling, packaging, and naming. V. Drug standardization, storage, and distribution. VI. Acquisition, use, and monitoring of devices for administering medications. VII. Environmental factors and human resources. VIII. Competence and training of healthcare workers in medications and safety practices. IX. Patient and family education. X. Quality programs and risk management.

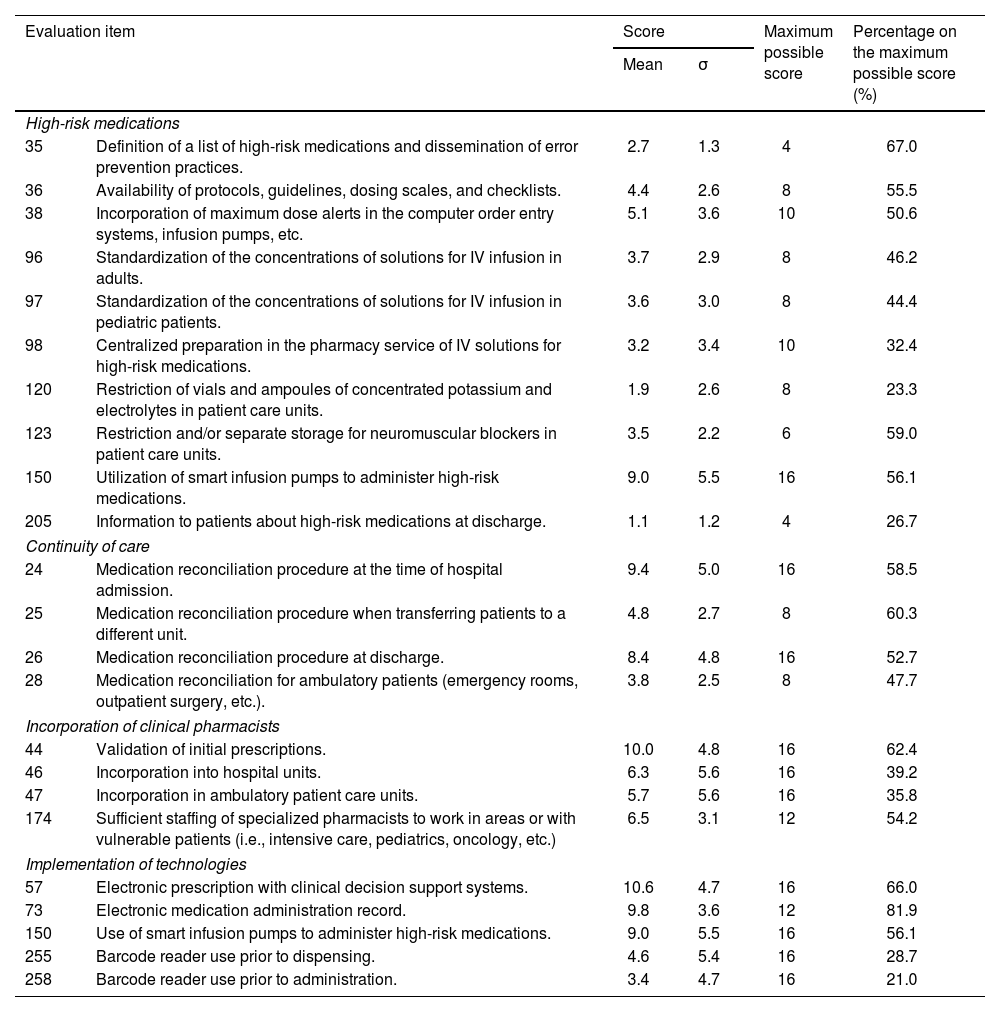

It is not possible to include the results obtained for each and every evaluation item in this article. Table 4 serves to illustrate the scores obtained for several items related to the safe use of high-risk medications and to medication reconciliation, which are considered priority areas in the third challenge of the World Health Organization (WHO), as well as for the incorporation of clinical pharmacists in healthcare teams and for technologies that impact safety, as recommended by expert organizations because of their proven efficacy in reducing medication errors. With respect to high-risk medications, low implementation percentages for the majority of items were observed, especially for item 120 (23.3%) which refers to removing vials or ampoules of concentrated potassium and electrolytes from patient care units, item 98 (32.4%) on centralized preparation in the pharmacy service of standardized intravenous solutions of high-risk medications, and item 205 (26.7%) on providing information about these medications to patients at the time of discharge. As far as establishing medication reconciliation practices, the mean percentages showed a broad range of improvement, both for reconciliation at the time of hospital admission (58.5%), when transferring patients to a different unit (60.3%), at discharge (52.7%) and in ambulatory care units (47.7%).

Results obtained in all hospitals (n=131) for several evaluation items related to high-risk medications, continuity of care, incorporation of clinical pharmacists, and implementation of technologies.

| Evaluation item | Score | Maximum possible score | Percentage on the maximum possible score (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | σ | ||||

| High-risk medications | |||||

| 35 | Definition of a list of high-risk medications and dissemination of error prevention practices. | 2.7 | 1.3 | 4 | 67.0 |

| 36 | Availability of protocols, guidelines, dosing scales, and checklists. | 4.4 | 2.6 | 8 | 55.5 |

| 38 | Incorporation of maximum dose alerts in the computer order entry systems, infusion pumps, etc. | 5.1 | 3.6 | 10 | 50.6 |

| 96 | Standardization of the concentrations of solutions for IV infusion in adults. | 3.7 | 2.9 | 8 | 46.2 |

| 97 | Standardization of the concentrations of solutions for IV infusion in pediatric patients. | 3.6 | 3.0 | 8 | 44.4 |

| 98 | Centralized preparation in the pharmacy service of IV solutions for high-risk medications. | 3.2 | 3.4 | 10 | 32.4 |

| 120 | Restriction of vials and ampoules of concentrated potassium and electrolytes in patient care units. | 1.9 | 2.6 | 8 | 23.3 |

| 123 | Restriction and/or separate storage for neuromuscular blockers in patient care units. | 3.5 | 2.2 | 6 | 59.0 |

| 150 | Utilization of smart infusion pumps to administer high-risk medications. | 9.0 | 5.5 | 16 | 56.1 |

| 205 | Information to patients about high-risk medications at discharge. | 1.1 | 1.2 | 4 | 26.7 |

| Continuity of care | |||||

| 24 | Medication reconciliation procedure at the time of hospital admission. | 9.4 | 5.0 | 16 | 58.5 |

| 25 | Medication reconciliation procedure when transferring patients to a different unit. | 4.8 | 2.7 | 8 | 60.3 |

| 26 | Medication reconciliation procedure at discharge. | 8.4 | 4.8 | 16 | 52.7 |

| 28 | Medication reconciliation for ambulatory patients (emergency rooms, outpatient surgery, etc.). | 3.8 | 2.5 | 8 | 47.7 |

| Incorporation of clinical pharmacists | |||||

| 44 | Validation of initial prescriptions. | 10.0 | 4.8 | 16 | 62.4 |

| 46 | Incorporation into hospital units. | 6.3 | 5.6 | 16 | 39.2 |

| 47 | Incorporation in ambulatory patient care units. | 5.7 | 5.6 | 16 | 35.8 |

| 174 | Sufficient staffing of specialized pharmacists to work in areas or with vulnerable patients (i.e., intensive care, pediatrics, oncology, etc.) | 6.5 | 3.1 | 12 | 54.2 |

| Implementation of technologies | |||||

| 57 | Electronic prescription with clinical decision support systems. | 10.6 | 4.7 | 16 | 66.0 |

| 73 | Electronic medication administration record. | 9.8 | 3.6 | 12 | 81.9 |

| 150 | Use of smart infusion pumps to administer high-risk medications. | 9.0 | 5.5 | 16 | 56.1 |

| 255 | Barcode reader use prior to dispensing. | 4.6 | 5.4 | 16 | 28.7 |

| 258 | Barcode reader use prior to administration. | 3.4 | 4.7 | 16 | 21.0 |

σ: standard deviation.

It was also possible to observe a low degree of incorporation of clinical pharmacists in hospitals units (39.2%) and in ambulatory care units (35.8%), which corresponds to the fact that the number of specialist pharmacists working in clinical units was considered insufficient by the participants (54.2%). Finally, with respect to the implementation of new technologies, higher scores were reported for electronic prescription with clinical decision-support systems (66%) and for electronic medication administration record (81.9%), and a low degree of implementation of barcode reader use in dispensing (28.7%) and when administering medications (21%).

DiscussionThis study provides detailed, up-to-date information regarding the implementation of safe practices in the medication use systems in Spanish hospitals, and will be of great usefulness at a critical moment when the WHO and other organizations are stressing the need to promote actions that will improve medication use safety, cognizant of the fact that preventable harm caused by medications constitutes an important concern for healthcare systems all over the world and that the problem has only been made exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.1,3,14,15

The results obtained show that appreciable advances have been made in the degree of implementation of some safety practices, yet there remains a broad margin for improvement if we are to truly reduce the risks associated with medication use in our hospitals. Moreover, the results reveal that the degree of implementation of safety practices is not the same across all hospitals. All of this reflects the great complexity and difficulties that we face when incorporating safe practices into the reality of hospital care.

It should be pointed out that multiple practices designed to improve the safety of high-risk medications and the continuity of medication during transitions of care continue to be poorly implemented, despite their being included in the National Strategy for Patient Safety16 and among the priority lines of the WHO.14 With respect to high-risk medications, the practice most widely implemented is having available at the hospital a list of high-risk medications, though this measure is of little value in itself if not accompanied by other more effective general or specific strategies, such as the inclusion of alerts within computer systems, standardization of concentrations of solutions for infusion and their preparation in the pharmacy service, restriction of potassium concentrates and neuromuscular blockers in the care units, etc.17,18 On the other hand, although the importance of implementing medication reconciliation procedures has been stressed,19,20 their incorporation into healthcare practice is still limited because they require infrastructures, human resources, and technologies that may not be available.

Scores were also low for those elements related to healthcare professionals’ competence and training with regard to error reduction practices and to educating patients and caregivers about medications, aspects that, according to the third challenge of the WHO, are fundamental pillars for improving safety,14 but ones that have not been integrated in organization and treatment procedures in our hospitals.

The study once again reveals that the incorporation of clinical pharmacists into our healthcare teams is sparse as is the provision of technologies that allow full traceability throughout the medication use system, such as barcode readers for use in dispensing and administration. This information coincides with data provided by The White Book SEFH-2019.21 Certainly, implementation of these practices has been for years and continues to be advocated by hospital pharmacists,22,23 since these practices have been shown to be among the most effective for reducing medication errors,24–27 but their implementation in our country is still lower than in others.28,29 One possible strategy for achieving a higher degree of implementation of safe practices as well as greater consistency among our hospitals would be to establish a certification system that would set minimum compulsory standards and, also, provide the resources necessary to guarantee those standards.

Finally, it should be pointed out that we believe this study has encouraged hospitals to use the self-assessment questionnaire and, in doing so, has also promoted analyses and reviews of all the processes in the medication use system and has identified areas of greatest risk, something that will incentivize healthcare professionals to seek measures for making improvements.

This study has numerous limitations stemming from the methodology used. First of all, there are the limitations associated with the inaccuracy of the self-assessment questionnaire, since it is really conceived as a tool for continuous quality improvement. Thus, interpretation of the different items on the questionnaire by the teams at each hospital may vary and affect results. In addition, although the instructions emphasize the importance of having a multidisciplinary group who are familiar with the reality at the hospital responding to the items with rigor and frankness, no control was carried out to verify compliance with these instructions, nor the veracity of the data recorded. Finally, we should point out that participation in the different autonomous regions was uneven and the hospitals were not randomly selected. Moreover, the hospitals that voluntarily decided to participate could be more sensitive and might put more effort into medication error prevention, which could have introduced bias into the results.

In conclusion, this study shows that appreciable advances have been achieved in the degree of implementation of some safe medication error prevention practices in Spanish hospitals, but numerous practices of proven efficacy recommended by the World Health Organization and by safety organizations are still only poorly implemented. The information we obtained from this study should prove useful for prioritizing the practices to be addressed and, also, as a new baseline for monitoring progress.

Contribution to the scientific literatureThe results of this study provide detailed, up-to-date information about safety in the medication use system in Spanish hospitals and should prove quite useful for prioritizing the practices to be addressed in efforts to make improvements.

The study clearly shows that appreciable advances have been made in the degree of implementation of some safety practices, though there is still ample room for improvement in order to achieve further reduction in the risks associated with medication use in hospitals.

Ethical considerationsThe article being submitted does not contain any identifiable patient data.

FundingThis study was carried out with the support of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH).

Authorship statementThis study was coordinated by MJO and JMC. All of the authors participated in disseminating the study and gathering information. The preliminary analysis and interpretation of the data was performed by MJO and MPE, and were later reviewed by the rest of the authors. All of the authors reviewed and contributed to writing the manuscript and approved the final version offered for publication.