To describe, analyse, and compare the situation of pharmaceutical care consultations for outpatients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases of the Pharmacy Services of Spain at 2 different times.

MethodLongitudinal, multicentre, and unidisciplinary descriptive observational study, carried out by the Immune-mediated Inflammatory Diseases Working Group of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy through a virtual survey in 2019 and 2021. Variables were collected regarding coordination, resources, biosimilars, unmet needs, and telepharmacy. Numerical results were presented in absolute value and percentage and free-text responses were grouped by topic areas. To compare the results between the 2 collection times, the Chi-Square test was used with a significance level of P < .05.

ResultsThe level of participation was 70 pharmacists in 2019 and 53 in 2021. The main significant findings obtained were an increase in participation in asthma biologic committees (P = .044) and care coordination in dermatology (P = .003) and digestive system (P = .022). The wide use of biosimilar biological medicines stood out, with a 15% increase in the exchange of the reference biological to the biosimilar. The lack of research in the field and insufficient human resources, among other unmet needs, were revealed. In the outpatient units, the use of the stratification model of the MAPEX project was a minority and an increase in the use of information and communication technologies was promoted. Motivated by the pandemic derived from COVID-19, telepharmacy was established for the first time in 85% of the centres, maintaining the service at 66% at the time of the second survey.

ConclusionsOutpatient units are undergoing constant change to adapt to new times, for which institutional support is needed to invest more resources to promote the development of strategies to reduce unmet needs. We must continue working to achieve a pharmaceutical practice that provides efficiency, safety, quality of life, and access to innovative drugs in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.

describir, analizar y comparar la situación de las consultas de atención farmacéutica a pacientes externos con enfermedades inflamatorias inmunomediadas de los Servicios de Farmacia de España antes y después de la primera ola de la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2.

Métodoestudio observacional descriptivo longitudinal, multicéntrico y unidisciplinar, realizado por el Grupo de Trabajo de Enfermedades Inflamatoria Inmunomediadas de la Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria mediante una encuesta virtual en 2019 y 2021. Se recogieron variables en materia de coordinación, recursos, biosimilares, necesidades no cubiertas y telefarmacia. Los resultados numéricos se presentaron en valour absoluto y porcentaje y las respuestas de texto libre se agruparon por áreas temáticas. Para la comparación de los resultados entre los dos momentos de recogida se utilizó la prueba Chi-Cuadrado con un nivel de significación de p < 0,05.

Resultadosel nivel de participación fue de 70 farmacéuticos en 2019 y 53 en 2021. Los principales hallazgos obtenidos fueron un incremento en la participación en comités de biológicos de asma (p = 0,044) y la coordinación asistencial en dermatología (p = 0,003) y aparato digestivo (p = 0,022). Destacó la amplia utilización de medicamentos biológicos biosimilares, con un aumento del 15% en el intercambio del biológico de referencia al biosimilar. Se puso de manifiesto la falta de investigación en el campo y la insuficiencia de recursos humanos, entre otras necesidades no cubiertas. En las unidades de pacientes externos la utilización del modelo de estratificación del proyecto MAPEX fue minoritario y se promovió un incremento en el uso de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación. Motivado por la pandemia derivada de la COVID-19, se instauró la telefarmacia por primera vez en el 85% de los centros, manteniendo el servicio en el 66% en el momento de realización de la segunda encuesta.

Conclusioneslas unidades de pacientes externos están en pleno cambio para adaptarse a los nuevos tiempos, para lo que se necesita apoyo institucional que invierta más recursos que permitan impulsar el desarrollo de estrategias para disminuir las necesidades no cubiertas. Debemos seguir trabajando para lograr una práctica farmacéutica que proporcione eficiencia, seguridad, calidad de vida y acceso a fármacos innovadores en los pacientes con enfermedades inflamatorias inmunomediadas.

In 2018, the Working Group on Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases (GTEII) was established within the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH). The group is coordinated by 10 hospital pharmacists (HPs) who provide daily pharmaceutical care (PC) consultations for patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID) in outpatient units. The objectives of the GTEII are as follows: to address therapeutic aspects, adherence, and patient-perceived health outcomes; to promote the continuing professional development of HPs working in this field; to conduct research and training projects aimed at evaluating health outcomes; and to raise awareness among patients and other healthcare professionals about the role of HPs in managing these diseases.1

The establishment of the GTEII was one of the main initiatives arising from the development of the stratification and PC model for IMID that took place within the Strategic Map of Outpatient Pharmaceutical Care (MAPEX) project, which is based on placing the patient at the centre of hospital pharmacy.2 Since 2014, extensive efforts have been focussed on addressing and understanding the current and future needs of outpatients. The collective result is the creation of the Outpatient Unit Certification Manual within the framework of the Quality-Pharmaceutical Excellence (Q-PEX) project.3 This manual outlines the actions to be promoted and developed by pharmacy services (PS) at the macro-, meso-, and micro-levels.

In 2020, activity in PC consultations changed drastically due to the emergence of type 2 coronavirus, which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2). We had to adapt to mobility restrictions and protect the health of our patients. Telepharmacy, which involves remote pharmacy practice using information and communication technologies (ICTs), became the main focus, especially during the first wave of the pandemic.4,5

The main objective of this study was to analyse, describe, and compare the state of PC consultations for outpatients with IMID in Spanish PSs, focusing on physical, human, and digital resources, the use of biosimilars, and unmet needs before and after the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

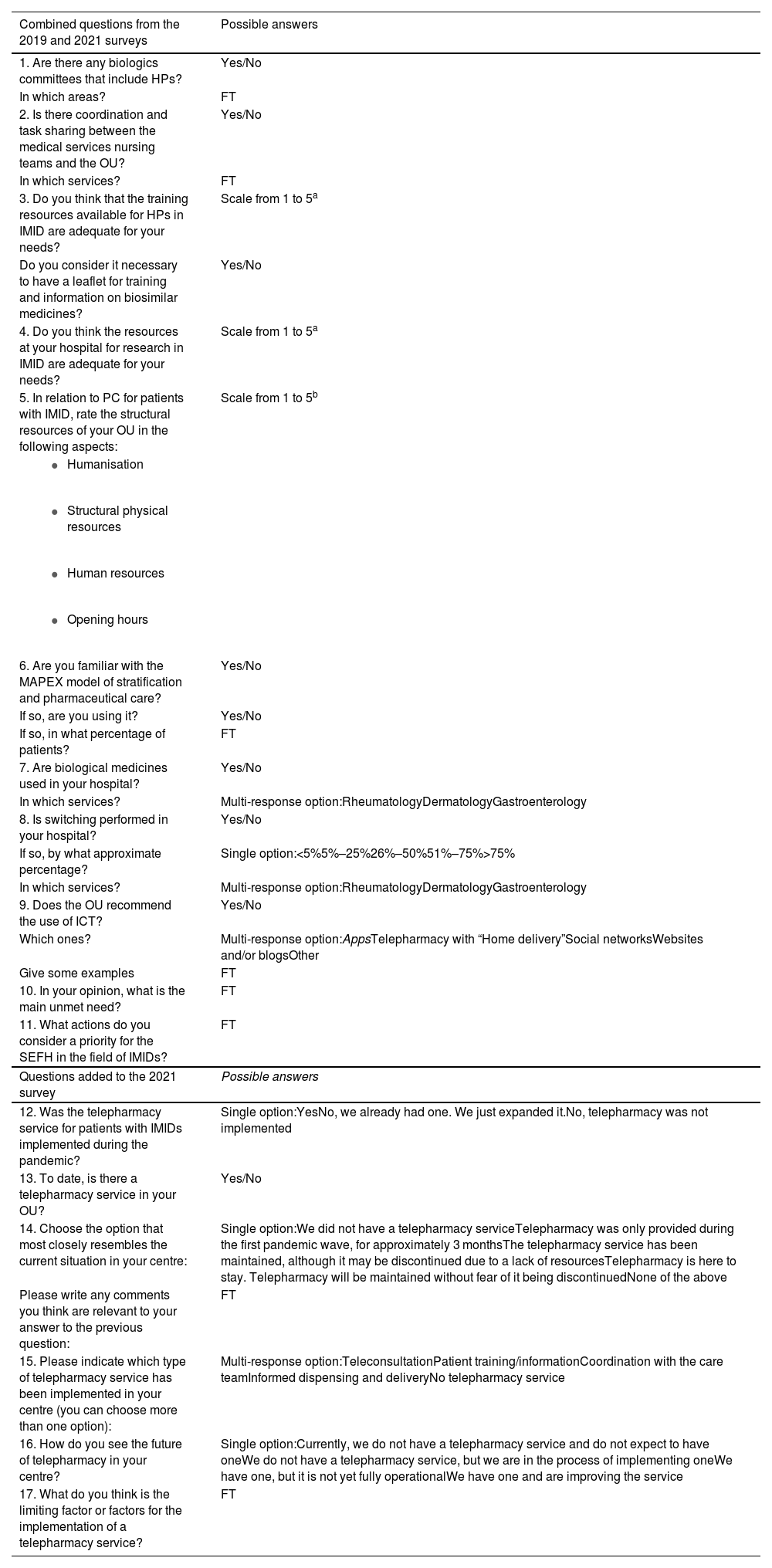

MethodsLongitudinal, multicentre, unidisciplinary, observational, descriptive study conducted by the GTEII through a virtual survey using the Google forms platform. The survey was distributed via the SEPH email distribution list (ListaSEFH) and the SEPH (Twitter and Instagram) and GTEII (Twitter) social media channels. The survey, designed by GTEII experts, was conducted over 2 time-periods. The first survey was conducted from May to October, 2019 and included 11 questions on the state of PC consultations for outpatients with IMID, as well as unmet needs. The second survey was conducted during the first half of 2021 and included 5 more questions addressing the evolution of PC for outpatients with IMID and the incorporation of telepharmacy into these consultations (total: 17 questions). This was done because the pandemic highlighted the need to conduct pharmaceutical care remotely, leading to the development of home delivery programs. Thus, we were able to collect a wide range of information about this novel situation (Table 1). Completion of both surveys was voluntary, anonymous, did not involve financial compensation, and both were specific to the PSs.

Survey on pharmaceutical care for outpatients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases and unmet needs.

| Combined questions from the 2019 and 2021 surveys | Possible answers |

|---|---|

| 1. Are there any biologics committees that include HPs? | Yes/No |

| In which areas? | FT |

| 2. Is there coordination and task sharing between the medical services nursing teams and the OU? | Yes/No |

| In which services? | FT |

| 3. Do you think that the training resources available for HPs in IMID are adequate for your needs? | Scale from 1 to 5a |

| Do you consider it necessary to have a leaflet for training and information on biosimilar medicines? | Yes/No |

| 4. Do you think the resources at your hospital for research in IMID are adequate for your needs? | Scale from 1 to 5a |

| 5. In relation to PC for patients with IMID, rate the structural resources of your OU in the following aspects: | Scale from 1 to 5b |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| 6. Are you familiar with the MAPEX model of stratification and pharmaceutical care? | Yes/No |

| If so, are you using it? | Yes/No |

| If so, in what percentage of patients? | FT |

| 7. Are biological medicines used in your hospital? | Yes/No |

| In which services? | Multi-response option:RheumatologyDermatologyGastroenterology |

| 8. Is switching performed in your hospital? | Yes/No |

| If so, by what approximate percentage? | Single option:<5%5%–25%26%–50%51%–75%>75% |

| In which services? | Multi-response option:RheumatologyDermatologyGastroenterology |

| 9. Does the OU recommend the use of ICT? | Yes/No |

| Which ones? | Multi-response option:AppsTelepharmacy with “Home delivery”Social networksWebsites and/or blogsOther |

| Give some examples | FT |

| 10. In your opinion, what is the main unmet need? | FT |

| 11. What actions do you consider a priority for the SEFH in the field of IMIDs? | FT |

| Questions added to the 2021 survey | Possible answers |

| 12. Was the telepharmacy service for patients with IMIDs implemented during the pandemic? | Single option:YesNo, we already had one. We just expanded it.No, telepharmacy was not implemented |

| 13. To date, is there a telepharmacy service in your OU? | Yes/No |

| 14. Choose the option that most closely resembles the current situation in your centre: | Single option:We did not have a telepharmacy serviceTelepharmacy was only provided during the first pandemic wave, for approximately 3 monthsThe telepharmacy service has been maintained, although it may be discontinued due to a lack of resourcesTelepharmacy is here to stay. Telepharmacy will be maintained without fear of it being discontinuedNone of the above |

| Please write any comments you think are relevant to your answer to the previous question: | FT |

| 15. Please indicate which type of telepharmacy service has been implemented in your centre (you can choose more than one option): | Multi-response option:TeleconsultationPatient training/informationCoordination with the care teamInformed dispensing and deliveryNo telepharmacy service |

| 16. How do you see the future of telepharmacy in your centre? | Single option:Currently, we do not have a telepharmacy service and do not expect to have oneWe do not have a telepharmacy service, but we are in the process of implementing oneWe have one, but it is not yet fully operationalWe have one and are improving the service |

| 17. What do you think is the limiting factor or factors for the implementation of a telepharmacy service? | FT |

PC, pharmaceutical care; IMID, immune-mediated inflammatory diseases; MAPEX, Mapa estratégico de Atención Farmacéutica al Paciente Externo; SEFH, Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy; ICT, information and communication technology; FT, free text; OU, outpatient unit.

We collected demographic variables related to the clinical practice of the responding HP (position held and years of experience) and OU data (total number of patients and those with IMID seen monthly).

The responses received were compiled in an Excel database, with restricted access to the study researchers. Each question was analysed collectively and separately.

A descriptive analysis of the responses was conducted, with qualitative variables expressed as numbers and percentages. Some questions were rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” or “very poor”, and 5 indicated “strongly agree” or “very good”. The free-text responses were grouped by theme to facilitate counting. The data collected in the 2 time-periods were compared using the chi-squared test in the IBM SPSS v.21 software package. A P-value of <.05 was used as a cut-off for statistical significance.

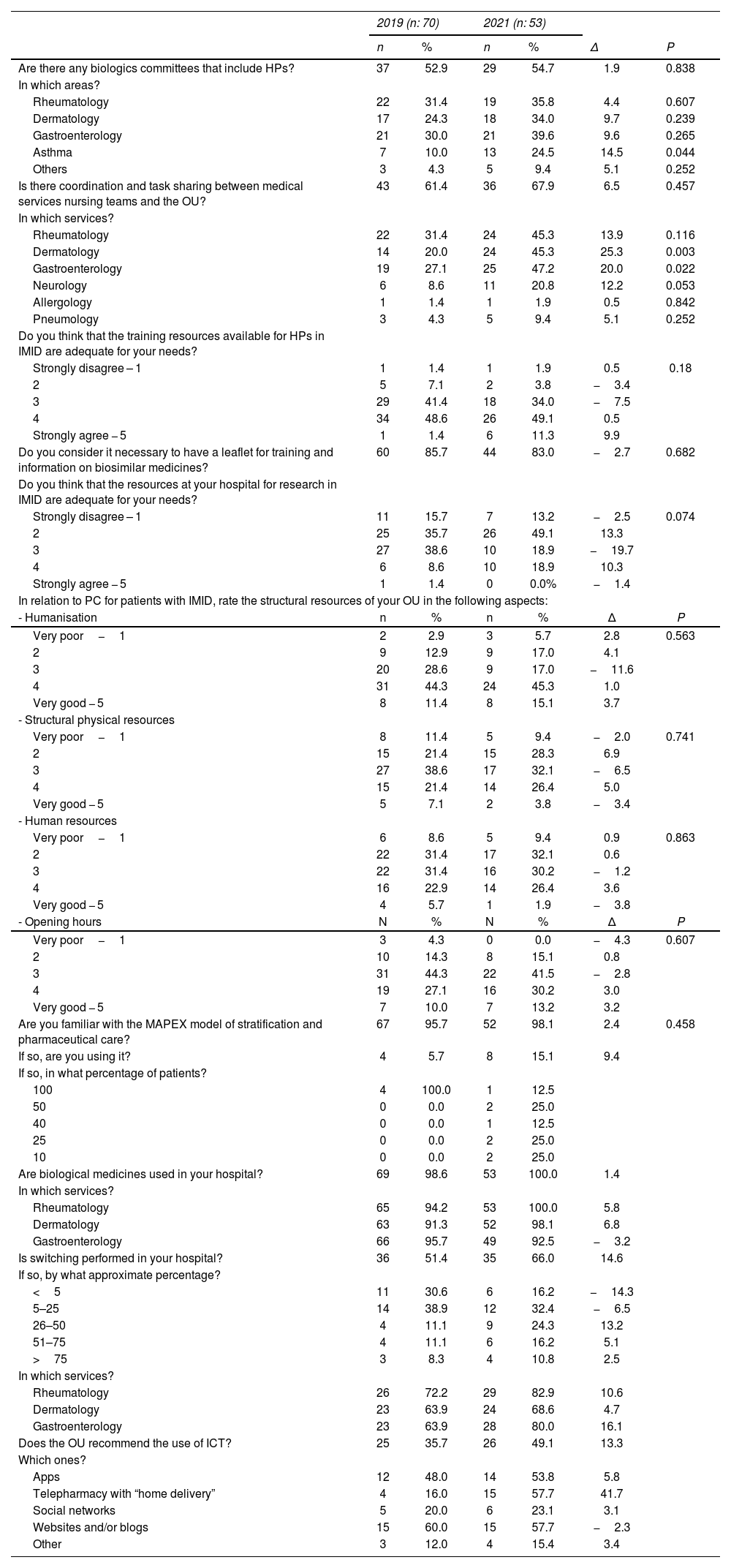

ResultsIn 2019, 70 HPs responded and in 2021, 53 responded. More than half of the HPs who responded during both periods were associate pharmacists (51.4% and 60.4%, respectively). Similarly, during both survey periods, over half the respondents had more than 5 years of experience (68.6 and 58.5%, respectively).

During both periods, more than half of the centres' OUs saw an average of 501–3000 total patients per month (58.6% in 2019 and 52.8% in 2021). More than half of the HPs saw between 101 and 500 IMID patients per month in both periods (51.4% in 2019 and 62.3% in 2021).

Between 2019 and 2021, there was a 1.9% increase in the creation of biologics committees (BCs). Most of them were affiliated with rheumatology, dermatology, and gastroenterology services. There was a notable statistically significant increase in asthma BCs (11.3%, P = .044).

However, there was no increase in the relationship and coordination between the medical services nursing teams and the OU, remaining practically at 50%. In the case of dermatology and gastroenterology, there was a statistically significant increase of 25.3% (P = .003) and 20.0% (P = .022), respectively.

The training resources available for HPs in IMID were considered adequate in both periods, with a 10% increase (50% in 2019 and 60% in 2021). In contrast, the proportion of respondents who considered it necessary to have a leaflet for training and information on biosimilar medicines decreased by 2.7%. In terms of research, both in the PSs and with multidisciplinary teams, more than half of the respondents felt that it was inadequate in both periods (51.4% in 2019 and 62.3% in 2021).

Regarding PC in patients with IMID, the provision of structural resources to cover aspects related to humanisation was considered good or very good by more than half of the respondents in both periods (55.7% in 2019 and 60.4% in 2021). However, in both survey periods, respondents were divided in their assessment of structural physical resources: 1/3 rated them as poor or very poor (32.9% and 37.7%, respectively), 1/3 as average (38.6% and 32.1%, respectively), and 1/3 as good or very good (28.6% and 30.2%, respectively). In both periods, human resources were considered poor or very poor (40%) or average (approximately 30%). Opening hours were considered average by 44% in 2019 compared to 41% in 2021, and good or very good by 37% in 2019 compared to 43% in 2021.

The great majority of HPs surveyed in 2019 and 2021 were aware of the MAPEX stratification and PC model (95.7% and 98.1%, respectively). However, it was only used by a minority: 5.8% (4 HPs) in 2019 and 15.1% (8 HPs) in 2021 (P = .083). Among those using the MAPEX stratification model, all 4 HPs reported using it in 100% of IMID patients, and in 2021, 1 HP reported using it in 100%, 2 in 50%, and 5 in 10%–40% of patients.

Overall, 98.6% of HPs were using biosimilars in 2019 and 100% in 2021, mainly in gastroenterology (95.7% and 92.5%, respectively), rheumatology (94.2% and 100%, respectively), and dermatology (91.3% and 98.1%, respectively). Switching to biosimilars increased from 51% in 2019 to 66% in 2021.

The use of ICTs was increasingly recommended by OUs: 36% in 2019 compared to 49% in 2021. In 2019, the most recommended ICTs were websites and blogs (60%) (e.g., https://www.tufarmaceuticodeguardia.org; https://edruida.com) and apps (48%) (e.g., RecuerdaMed and other medication reminder apps). In 2021, websites and blogs remained prominent at 57.7% (e.g., patient association websites), while apps were recommended by 53.8%. In addition, there was a significant 41.7% increase in telepharmacy through video consultations and in delivering patient medications to the closest healthcare centres or pharmacies using courier services.

In 2019, the most frequent unmet needs, in descending order, were human and structural resources, training, ICT and information systems, coordination and integration with the healthcare team, and time available for PC. In 2021, they were human resources, time available for PC and pharmacotherapeutic monitoring, structural resources, training, ICT and information systems, patient information, home dispensing, and specialised consultations.

In 2019, the actions most often considered to be priorities, in descending order, were HP training, providing patient information and training, development of consensus documents and guidelines, coordination and participation of HPs with care teams, identification of needs to achieve adequate PC in IMID, protocolisation and positioning of cost-effective treatments, and support for biosimilars and research. In 2021, they were HP training, providing patient information and training, development of consensus documents and guidelines, protocolisation and positioning of cost-effective treatments, the use of ICT (websites, blogs, apps), and support for research.

Regarding the questions on telepharmacy in 2021 alone, 85% of HPs stated they had first used telepharmacy during the pandemic. However, at the time of the survey, only 66% of HPs maintained a telepharmacy service, while one-third (32%) of those who had started one maintained it as an established activity. Overall, 81% provided informed dispensing and delivery, 53% used teleconsultation, and 32% provided patient education and information. In a third of the cases, there was coordination with the care team. More than half (66%) considered human resources to be the limiting factor, ahead of material resources (49%), and institutional support (38%). As proposals for the implementation of telepharmacy, they recommended establishing partnerships with community pharmacies and health centres.

Table 2 details the questions and answers in both surveys.

Survey questions and answers.

| 2019 (n: 70) | 2021 (n: 53) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Δ | P | |

| Are there any biologics committees that include HPs? | 37 | 52.9 | 29 | 54.7 | 1.9 | 0.838 |

| In which areas? | ||||||

| Rheumatology | 22 | 31.4 | 19 | 35.8 | 4.4 | 0.607 |

| Dermatology | 17 | 24.3 | 18 | 34.0 | 9.7 | 0.239 |

| Gastroenterology | 21 | 30.0 | 21 | 39.6 | 9.6 | 0.265 |

| Asthma | 7 | 10.0 | 13 | 24.5 | 14.5 | 0.044 |

| Others | 3 | 4.3 | 5 | 9.4 | 5.1 | 0.252 |

| Is there coordination and task sharing between medical services nursing teams and the OU? | 43 | 61.4 | 36 | 67.9 | 6.5 | 0.457 |

| In which services? | ||||||

| Rheumatology | 22 | 31.4 | 24 | 45.3 | 13.9 | 0.116 |

| Dermatology | 14 | 20.0 | 24 | 45.3 | 25.3 | 0.003 |

| Gastroenterology | 19 | 27.1 | 25 | 47.2 | 20.0 | 0.022 |

| Neurology | 6 | 8.6 | 11 | 20.8 | 12.2 | 0.053 |

| Allergology | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.842 |

| Pneumology | 3 | 4.3 | 5 | 9.4 | 5.1 | 0.252 |

| Do you think that the training resources available for HPs in IMID are adequate for your needs? | ||||||

| Strongly disagree – 1 | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.18 |

| 2 | 5 | 7.1 | 2 | 3.8 | −3.4 | |

| 3 | 29 | 41.4 | 18 | 34.0 | −7.5 | |

| 4 | 34 | 48.6 | 26 | 49.1 | 0.5 | |

| Strongly agree − 5 | 1 | 1.4 | 6 | 11.3 | 9.9 | |

| Do you consider it necessary to have a leaflet for training and information on biosimilar medicines? | 60 | 85.7 | 44 | 83.0 | −2.7 | 0.682 |

| Do you think that the resources at your hospital for research in IMID are adequate for your needs? | ||||||

| Strongly disagree – 1 | 11 | 15.7 | 7 | 13.2 | −2.5 | 0.074 |

| 2 | 25 | 35.7 | 26 | 49.1 | 13.3 | |

| 3 | 27 | 38.6 | 10 | 18.9 | −19.7 | |

| 4 | 6 | 8.6 | 10 | 18.9 | 10.3 | |

| Strongly agree − 5 | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.4 | |

| In relation to PC for patients with IMID, rate the structural resources of your OU in the following aspects: | ||||||

| - Humanisation | n | % | n | % | Δ | P |

| Very poor−1 | 2 | 2.9 | 3 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 0.563 |

| 2 | 9 | 12.9 | 9 | 17.0 | 4.1 | |

| 3 | 20 | 28.6 | 9 | 17.0 | −11.6 | |

| 4 | 31 | 44.3 | 24 | 45.3 | 1.0 | |

| Very good − 5 | 8 | 11.4 | 8 | 15.1 | 3.7 | |

| - Structural physical resources | ||||||

| Very poor−1 | 8 | 11.4 | 5 | 9.4 | −2.0 | 0.741 |

| 2 | 15 | 21.4 | 15 | 28.3 | 6.9 | |

| 3 | 27 | 38.6 | 17 | 32.1 | −6.5 | |

| 4 | 15 | 21.4 | 14 | 26.4 | 5.0 | |

| Very good − 5 | 5 | 7.1 | 2 | 3.8 | −3.4 | |

| - Human resources | ||||||

| Very poor−1 | 6 | 8.6 | 5 | 9.4 | 0.9 | 0.863 |

| 2 | 22 | 31.4 | 17 | 32.1 | 0.6 | |

| 3 | 22 | 31.4 | 16 | 30.2 | −1.2 | |

| 4 | 16 | 22.9 | 14 | 26.4 | 3.6 | |

| Very good − 5 | 4 | 5.7 | 1 | 1.9 | −3.8 | |

| - Opening hours | N | % | N | % | Δ | P |

| Very poor−1 | 3 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 | −4.3 | 0.607 |

| 2 | 10 | 14.3 | 8 | 15.1 | 0.8 | |

| 3 | 31 | 44.3 | 22 | 41.5 | −2.8 | |

| 4 | 19 | 27.1 | 16 | 30.2 | 3.0 | |

| Very good − 5 | 7 | 10.0 | 7 | 13.2 | 3.2 | |

| Are you familiar with the MAPEX model of stratification and pharmaceutical care? | 67 | 95.7 | 52 | 98.1 | 2.4 | 0.458 |

| If so, are you using it? | 4 | 5.7 | 8 | 15.1 | 9.4 | |

| If so, in what percentage of patients? | ||||||

| 100 | 4 | 100.0 | 1 | 12.5 | ||

| 50 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 25.0 | ||

| 40 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 12.5 | ||

| 25 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 25.0 | ||

| 10 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 25.0 | ||

| Are biological medicines used in your hospital? | 69 | 98.6 | 53 | 100.0 | 1.4 | |

| In which services? | ||||||

| Rheumatology | 65 | 94.2 | 53 | 100.0 | 5.8 | |

| Dermatology | 63 | 91.3 | 52 | 98.1 | 6.8 | |

| Gastroenterology | 66 | 95.7 | 49 | 92.5 | −3.2 | |

| Is switching performed in your hospital? | 36 | 51.4 | 35 | 66.0 | 14.6 | |

| If so, by what approximate percentage? | ||||||

| <5 | 11 | 30.6 | 6 | 16.2 | −14.3 | |

| 5–25 | 14 | 38.9 | 12 | 32.4 | −6.5 | |

| 26–50 | 4 | 11.1 | 9 | 24.3 | 13.2 | |

| 51–75 | 4 | 11.1 | 6 | 16.2 | 5.1 | |

| >75 | 3 | 8.3 | 4 | 10.8 | 2.5 | |

| In which services? | ||||||

| Rheumatology | 26 | 72.2 | 29 | 82.9 | 10.6 | |

| Dermatology | 23 | 63.9 | 24 | 68.6 | 4.7 | |

| Gastroenterology | 23 | 63.9 | 28 | 80.0 | 16.1 | |

| Does the OU recommend the use of ICT? | 25 | 35.7 | 26 | 49.1 | 13.3 | |

| Which ones? | ||||||

| Apps | 12 | 48.0 | 14 | 53.8 | 5.8 | |

| Telepharmacy with “home delivery” | 4 | 16.0 | 15 | 57.7 | 41.7 | |

| Social networks | 5 | 20.0 | 6 | 23.1 | 3.1 | |

| Websites and/or blogs | 15 | 60.0 | 15 | 57.7 | −2.3 | |

| Other | 3 | 12.0 | 4 | 15.4 | 3.4 | |

PC, pharmaceutical care; HP, hospital pharmacist; IMID, immune mediated inflammatory diseases; MAPEX, Strategic Map of Outpatient Pharmaceutical Care; ICT, information and communication technology; OU, outpatient unit.

The results of the surveys conducted in 2019 and 2021 show that some aspects continued to evolve, while others remained stable. Although participation was lower in 2021, the results of the comparisons were calculated as percentages while taking into account statistical significance.

Hospital pharmacists are increasingly integrated into multidisciplinary teams; however, only slightly more than half of the respondents participate in BCs. With the increasing use of biologics, BCs have been established in hospitals to manage the selection of these drugs in different situations, and in some cases, HPs advocate for their establishment. However, it is not mandatory to establish BCs, nor are their characteristics defined. Just as the roles within Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs are clearly established, it would be useful to have similar guidelines concerning the members of BCs. In this way, we could define the roles of each professional within the team and involve different specialists, nursing staff, and patients.

There was an increase in coordination and task-sharing between PS nursing teams and OUs, which was statistically significant in the dermatology and gastroenterology services. Communication between medical services and PSs is essential in order to coordinate patient-facing activities as much as possible. Duplication of effort should be avoided in order to increase the effectiveness of the teams, always focusing on the needs of the patients.6

The 2019 survey revealed the need to expand IMID training. Over the last 2 years, the increase in both online and in-person training activities (such as disease-specific continuing professional development programmes, pharmaceutical practice guidelines, workshops, projects, etc) and the resources produced by the GTEII group has led to an increase in the percentage of HPs who consider the training on these diseases to be adequate. However, expanding training remains a key objective among the tasks of the GTEII group.

There is still room for improvement in addressing research needs in IMID diseases. There are significant differences among the various centres, and some have not experienced progress since the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since the establishment of the GTEII group, pharmacotherapy for IMIDs has been impacted by the introduction of biosimilars. This prompted our initial projects to focus on promoting their use and effectively communicating their advantages to other healthcare professionals and patients. One of the projects developed by GTEII is BIOINFO, which focuses on the use of explanatory leaflets on biological medicines in general and on biosimilars in particular. The non-significant decrease in the percentage of HPs who saw the need for explanatory leaflets on biosimilars between the 2 surveys could be attributed to the growing familiarity and acceptance of these drugs among health professionals and patients.

Regarding the use of biosimilars, effective communication with prescribing medical services and with patients7 has been crucial for integrating these biologics into pharmacotherapeutic protocols, both for initiating treatment with biosimilars and transitioning between reference biologics to biosimilars, a process known as “switch” or “switching”.8–10 The high percentage of biosimilar use seen in both study periods, along with the increase in switching observed, clearly reflects the effort made by PSs. This has been reflected in the reduction of biologic treatment costs, not only for patients starting these drugs, but also for those already on them who have been switched. In 2021, we observed an increase in this practice, likely due to accumulating evidence on the positive outcomes of using these drugs. The switch to biosimilars has not resulted in a loss of efficacy or safety, nor has it increased the immunogenicity of the different IMIDs.11 García-Beloso et al. (2021) found that 80.7% of patients who switched to the infliximab biosimilar achieved an Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society 20 response after 2 years, compared to 76.9% of patients who continued using the original biologic drug.12 Good coordination between the medical and HP teams is essential to make this switch a success and to prevent issues such as the nocebo effect.13

HPs rated PC as good in terms of humanisation. For many years, humanisation has been an integral part of every health care process.14,15 The SEPH published a Humanisation Guide in 2020.16 Recently, an appendix has been added for the management of patients with IMID,17 with the aim of encouraging practices that improve the overall experience of these patients from a holistic perspective.

Recommendations on ICT have evolved from suggesting only websites, blogs, and apps to now also including information on patient associations, Twitter accounts, and communication through video consultations and/or email. This broader approach facilitates telepharmacy and delivery of medications. Patients are increasingly demanding the use of these ICTs to interact with each other and stay informed. There has been a perceived shift toward optimising interactions between professionals and patients, aiming to provide more personalised care through the patients' own mobile phones.18

In 2018, an anonymous survey was conducted among patients with various chronic diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatological conditions. They were asked to rate their experience with the healthcare system on the Instrument for Assessment of the Chronic Patient Experience scale.19 This questionnaire identified areas for improvement in the care of chronic patients, especially those concerning access to reliable sources of information, interaction with other patients, and continuity of care following hospital admission.

The HPs highlighted shortcomings in human and structural resources as an ongoing unmet need persisting from year to year. Improving the availability of resources would allow for more time dedicated to PC and to both individual and collective training in various subjects, including ICT. In this regard, the GTEII can help improve the situation by organising webinars and courses to keep knowledge about IMIDs current, creating material for patients, developing consensus documents and pharmaceutical practice guidelines, promoting coordination, cooperation, and participation with healthcare teams, and establishing the requirements for effective PC in IMIDs.

Prior to the health crisis, Tortajada-Goitia et al. (2020) found that 83.2% of public health services did not conduct remote PC activities that included telepharmacy with remote medication delivery.20 However, the COVID-19 pandemic prompted many PSs to implement telepharmacy in record time. Unfortunately, not all services were able to maintain telepharmacy practices after the immediate crisis, highlighting the need for continued institutional support in each centre. The SEPH has issued a position statement and support documents for its implementation and to underscore the need for telepharmacy in all hospitals in Spain.21 After the most challenging years of the pandemic, there is a need for institutional support to provide the necessary human and material resources to sustain telepharmacy.

In this sense, the Q-PEX project aims to provide support and give a significant boost to our collective through a model of professional quality that, based on the latest available evidence, is designed to transform and add value to the essential elements for achieving and sustaining these quality standards over time. This will result in the best health outcomes and the most positive pharmacotherapeutic experience for both our patients and all the professionals who work with us.

The limitations of our study include the different characteristics of each centre and the limited number of responses received. However, the information presented provides insights beyond those of any single service, offering a valuable foundation for the GTEII's strategic planning.

Outpatient units are in the midst of change to adapt to the new realities. Institutional support is needed that recognises the need to invest in increased human and material resources in these units. Such support would provide an impetus to develop strategies to reduce the unmet needs of our patients. To achieve this, we must take into account patients with IMID and involve them in the change process.

The information gathered from the surveys in both collection periods has enhanced our understanding of the differences between the various OUs.

The GTEII will continue to work to ensure that the OUs for IMID conditions are as homogeneous as possible, allowing for pharmaceutical practices that provide efficiency, safety, quality of life, and access to innovative drugs for patients with IMID.

Contribution to the scientific literatureThere has been a noticeable increase in involvement in multidisciplinary teams, including greater participation in biologics committees, improved care coordination, and increased use of biosimilars.

Noteworthy is the establishment of telepharmacy for the first time in 85% of the centres, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ethical responsibilitiesThis research did not involve patients and did not process patient data.

It involved a virtual survey conducted using the Google Forms platform and was sent to the SEPH members' email distribution list. At all times, voluntary participation and privacy protection were ensured.

FundingNone declared.

Declaration of authorshipPiedad López Sánchez contributed to the concept, design, definition of intellectual content, literature search, data collection and analysis, statistical analysis, preparation, editing, and revision of the manuscript, and is the author responsible for the present work. Tomás Palanques Pastor participated in defining the intellectual content, literature search, data analysis and preparation, and editing and revising the manuscript. Olatz Ibarra Barrueta collaborated in the concept, design, editing, and revision of the manuscript. Esther Ramírez Herráiz contributed to the concept, design, literature search, and revision of the manuscript. Míriam Casellas Gibert participated in the revision of the manuscript. Emilio Monte Boquet contributed to the concept, data collection, editing, and revision of the manuscript.

Conference presentationsEuropean Association of Hospital Pharmacists, Bordeaux (France), March 2024.

Responsibilities and assignment of rightsAll authors accept the responsibilities defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (available at http://www.icmje.org/.

In the event of publication, the authors grant exclusive rights of reproduction, distribution, translation, and public communication (by any medium or sound, audiovisual, or electronic support) of their work to Farmacia Hospitalaria and, by extension, to the SEFH. To this end, a letter of transfer of rights will be signed at the time of submission of the paper through the online manuscript management system.

CRediT authorship contribution statementPiedad López Sánchez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Tomás Palanques Pastor: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Olatz Ibarra Barrueta: Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Esther Ramírez Herráiz: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Míriam Casellas Gibert: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Emilio Monte Boquet: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.