Adherence to treatment in patients living with HIV remains the focus of attention of health professionals and researchers. However, patient profiles and the available therapeutic arsenal have changed greatly over the last decade. Inadequate adherence not only to antiretroviral therapy but also to other prescribed drugs remains the main cause of therapeutic failure. There are several factors associated with poor adherence and others that facilitate it, hence the importance of identifying, managing and correcting situations that may hinder adherence. Likewise, adherence should be periodically reassessed during the follow-up of ART and other prescribed drugs.

It has so far proved impossible to find a single method capable of providing a reliable measurement of adherence. That is why it is necessary to use a combination of multiple easy-to-implement methods. Additionally, a good relationship with the patient facilitates the conveyance of adequate information on adherence. It is currently considered that interventions to improve adherence should be multidisciplinary, individualized and adjusted to the new patterns of infection transmission, and that controlling adherence to other drugs prescribed to patients with HIV should be part of such interventions.

This document provides an update on the recommendations published in 2008 based on a review of the scientific literature. The main goal is to help healthcare professionals dedicated to the clinical and therapeutic management of HIV patients (doctors, pharmacists, nurses, psychologists and social workers) improve adherence of such patients to all the drugs prescribed to them as treatment for their HIV infection.

La adherencia al tratamiento en el paciente con infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana sigue siendo foco de atención de profesionales sanitarios e investigadores. Sin embargo, el perfil del paciente y el arsenal terapéutico disponible han cambiado enormemente en la última década. La adherencia inadecuada, no solo al tratamiento antirretroviral sino también a otros fármacos prescritos, sigue siendo la principal causa de fracaso terapéutico. Existen diversos factores asociados a la mala adherencia y otros que facilitan la misma, de ahí la importancia de identificar y manejar las situaciones que puedan dificultar la adherencia e intentar corregirlas. Asimismo, se debe reevaluar periódicamente la adherencia durante el seguimiento del tratamiento antirretroviral y del resto de los fármacos prescritos.

En la actualidad no existe un método único para medir la adherencia de forma fiable. Por ello se hace necesario utilizar varios métodos combinados de fácil realización. Adicionalmente, una buena relación entre el personal sanitario y los pacientes facilita la obtención de una adecuada información sobre la adherencia. Las intervenciones para mejorar la adherencia deben ser multidisciplinares, individualizadas y ajustadas a los nuevos patrones de transmisión de la infección, y es fundamental incluir el control de la adherencia a otros fármacos prescritos al paciente con el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana.

El presente documento actualiza las recomendaciones publicadas en 2008 tras una revisión de la literatura científica, lo que ha permitido emitir unas recomendaciones consensuadas para la mejora de la adherencia al tratamiento. El objetivo principal es ayudar a todos los profesionales sanitarios dedicados al control clínico y terapéutico de los pacientes con el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (médicos, farmacéuticos, enfermeras, psicólogos y trabajadores sociales) a mejorar la adherencia a toda la farmacoterapia que tengan prescrita.

In 19991,2 the Secretariat of the Spanish AIDS Plan, the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmaceutics (SEFH) and GeSIDA (AIDS Study Group) first published a series of recommendations intended to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Such recommendations were updated in 2004 and 20083,4. Over 10 years on, adherence to treatment remains a priority for healthcare professionals and an area of great interest for researchers. For that reason, providing an update on the latest recommendations published, incorporating the current guidelines regarding antiretroviral treatment (ART), seems a useful endeavor5.

Inadequate adherence of adult patients with HIV not just to ART but to other drugs remains the leading cause of therapeutic failure. Given that different factors have been suggested as culprits or at least facilitators of poor adherence, the onset of ART should always be preceded by careful preparation, a systematic identification of factors capable of hindering adherence, and an effort to address them. At the same time, a periodical evaluation of adherence must be made for the duration of treatment with both antiretrovirals and other drugs prescribed.

The present study summarizes the contents of a document that provides an update on the recommendations published in 2008, based on a review of the scientific literature. The said document contains series of consensual recommendations for the enhancement of adherence and lays special emphasis on some innovative aspects not included in the previous set of recommendations. The purpose is to help healthcare professionals dedicated to the clinical and therapeutic control of HIV patients improve adherence to the entire course of medication.

In the future, the Secretariat of the Spanish AIDS Plan will work together with the different scientific societies involved to keep this document updated, thereby reflecting the evolution of the state of the art in the realm of adherence to treatment among HIV patients. Nonetheless, given that research in this area is subject to constant evolution, readers would be well advised to turn to additional sources of information.

MethodsThe Secretariat of the Spanish AIDS Plan, the Board of Trustees of GeSIDA and the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmaceutics (SEFH) entrusted a group of clinicians with experience in HIV infection and ART with the task of updating the 2008 recommendations. Clinicians were distributed into a drafting and a review panel. Three members of the panel (representing the Spanish AIDS Plan, GeSIDA and SEFH) acted as coordinators, with the mission of reviewing the final document. The coordinator appointed by the Spanish AIDS Plan was the one in charge of putting together all the different sections of the document and overseeing the final text. The members of the drafting group reviewed the most significant data contained in English and Spanish-language scientific papers published from 2008 to 30 November 2019 (PubMed and Embase). The text prepared by the drafting group was subjected to the consideration of the reviewers, whose contributions were added on a consensual basis. Once all the sections were put together, the document was discussed and agreed upon during an audio conference call. After incorporation of the changes approved at that meeting, the document was posted on the respective websites of the Spanish Aids Plan, GeSIDA and SEFH for 15 days to seek feedback on the proposed recommendations. The suggestions received were analyzed and debated, and as decision was made regarding their inclusion in the final document. Recommendations were based on scientific evidence and expert opinion and classified with a letter that indicated the degree to which they should be implemented: ([A: to be implemented at all times], B [to be implemented as a general rule] and C [to be implemented optionally]), and a number designating the strength of the evidence available (I [results obtained from one or more randomized clinical trials or a meta-analysis]; II [one or more non-randomized trials or observational cohort studies]; and III [expert opinion]).

ResultsFor want of a universally accepted definition, and given the new patient profiles and the new ways of treating HIV patients, adherence was defined as “the ability of a patient to become appropriately involved in the choice, initiation and monitoring of their pharmacological regimen in such a way as to achieve, wherever possible, the pharmacotherapeutic goals pursued, considering their individual clinical status and health expectations”.

This definition, which pivots on the role of ART as the mainstay in the treatment of patients with HIV, underscores the increasingly important role of the concomitantly prescribed medication6.

Poor adherence does not only refer to failure to take the prescribed dose of a given drug; other factors also play a decisive role (see below)7. Shortand medium/long-term adherence is the result of a process that comprises several stages: accepting the diagnosis; acquiring the perception of the need to follow the treatment correctly and the personal motivation to do so; developing the willingness and the skills required to comply; demonstrating the ability to overcome any hurdles that may arise; and preserving the achievements made over time8.

According to an old classification, non-adherence could be intended or unintended, depending on whether the patient is believed to have made a self-determined decision not take their medication correctly. At present, non-adherence is classified into primary non-adherence, which refers to the period elapsed between the time of prescription and the time the prescribed drug is available to the patient, and secondary non-adherence, which measures the use of the drug by the patient over time, according to the recommendations made. It is important to take into account that non-adherence may occur in either of those areas or in both at the same time9. This is why, when conducting evaluations to improve adherence, it is essential to include not only ART but also all the other drugs prescribed to the patient.

This document comprises the following sections:

- I.

Factors influencing adherence.

- II.

Methods used to determine adherence.

- III.

Strategies to improve adherence.

- IV.

Prescription, dispensation and monitoring procedures.

There are multiple limitations that make it difficult to extrapolate the results of the different studies attempting to identify the factors influencing adherence, including the method used to determine adherence; the diversity of aspects evaluated; the population considered; and the design of the study itself. Such factors may be related to the subject, the treatment, the clinical team or the healthcare system (table 1). Table 2 summarizes the recommendations and the degree of implementation of the different measures used to address adherence-related issues in adult and adolescent patients.

Factors related with inadequate adherence to antiretroviral treatment

| PATIENT | HEALTHCARE STAFF | TREATMENT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Attitudes | ||

|

| ||

Recommended interventions to address adherence difficulties in adults and adolescents

| Patient | Factor | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| With the individual |

| |

| Disease and comorbidities | The initial severity of infection and CD4 cell count should not influence adherence to a given ART. (B-II) Depressive symptoms should be proactively addressed as they tend to be associated to poor adherence. (B-II) | |

| Adult | Treatment |

|

| Healthcare team |

| |

| Adolescent |

|

ART: antiretroviral treatment.

It is important to point out that adolescents with an HIV infection tend to find it more difficult to adhere to their treatment and the recommendations of the healthcare system than adults, given the lower levels of autonomy and privacy they usually enjoy10. In those patients, adherence tends to be compromised because they usually attach great importance to the “here and now” and to being accepted by their peers, without stopping to consider the risk that non-adherence poses for their own health2. In addition, infection constitutes a social stigma that could in turn influence their adherence to ART. In these patients, the treatment regimen should be simplified to one daily administration; a reduction in the number of tablets they took during childhood; and the use of combined preparations, with a focus on avoiding side effects. This should allow them an activity level akin to that of their peers11,12. Adolescents with a perinatal infection usually experience considerable fatigue as a result of the medication they take. Psychosocial and behavioral factors have been identified in these patients, which have been associated to poorer adherence13–15.

Techniques such as directly observed therapy (DOT), psychological support, peer-to-peer support programs, pharmacy department monitoring as well as ICTs such as electronic alarms, text messages or apps can also be used to great advantage with these patients16–17.

II. Methods used to determine adherenceThe ideal method should be highly sensitive and specific. It should allow for quantitative and continuous measurements, it should be reliable, reproducible and capable of detecting changes in adherence over time, and it should be applicable to different situations, as well as fast and economical. However, there is no such thing as an ideal method, which emphasizes the importance of understanding the strengths and limitations of each one of the methods commonly applied.

Methods used to determine adherence can be classified into direct and indirect.

1. Direct methods

1.1. Serum concentrations

Although this is considered the most objective method, it is associated with significant limitations. The literature highlights several controversies regarding this method. Despite multiple reports has found lower serum levels in non-adherent patients and a solid correlation between serum concentrations and questionnaire results, adequate serum levels have been found in a significant number of non-adherent subjects’ self-reports18,19. Other studies, where this method is the only one used to determine adherence, did not find significant differences with respect to viral load control20–22. Some authors, however, have shown that drug serum levels constitute a variable capable of predicting a subject's virologic response in an independent way, while others have found that variable to be associated to acceptable sensitivity but low specificity for identification of the virologic response23–25.

It is also important to consider that there are a series of intra- and interindividual variables that have an impact on the kinetic behavior of antiretroviral drugs. The establishment of a standard threshold to tell adherent from non-adherent patients seems at best questionable. It would be necessary to take several measurements for each patient as well as to conduct population-based pharmacokinetic studies to gain a precise understanding of the factors affecting the kinetic profile of each individual drug, or at least of the pharmacologic groups they may belong to. Although inroads have been made into these areas, it has as yet not been possible to obtain precise data outside the realm of research26.

Lastly, it should be mentioned that this method requires a series of expensive and complex analytical techniques, which precludes its application to everyday practice.

Other analytical methods have been tested in terms of their ability to accurately determine adherence and/or cumulative drug exposure (dry blood spot sampling, hair sampling) with variable results but with potential usefulness in low-resource geographies.

1.2. Clinical evolution and analytical data

Clinical evolution and virologic and immunologic analyses should not be considered adherence determination methods but rather a result of a subject's level of adherence.

Undetectable viral load is not a perfect indicator of high adherence to ART and does not provide any information on adherence patterns. Patients with virologic suppression and suboptimal adherence have been seen to exhibit higher levels of inflammation and coagulopathy markers27. Lastly, immunovirologic monitoring used as an adherence determination method cannot be applied to the use of PrEP.

2. Indirect methods

Table 3 includes the different indirect methods with their advantages and limitations.

Methods to measure adherence in VIH patients: specific recommendations, advantages and limitations

| Method | Recommendations | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct |

| Direct methods tend to be rather unspecific, which makes them unsuitable for individualized use. | |

| Indirect | |||

| Evaluation by the healthcare staff |

| Simplicity. | They tend to overestimate adherence, which may result in suboptimal decisionmaking. |

| Electronic monitoring | Using a Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) as a method of reference to validate other methods. (A-I) | These systems have shown to be more reliable and to provide a better correlation with the treatment's virologic efficacy. They provide information on the evolution of adherence patterns over time. |

|

| Counting leftover medication | Counting leftover medication is an acceptable method but is should be used together with other methods. (B-II) | Low-cost. Well correlated with virologic efficacy. |

|

| Dispensation registers | These registers should be used together with other methods given that being in possession of the medication does not necessarily imply ingesting it, or doing so in the right way. (B-II) |

|

|

| Self-reported adherence questionnaires |

|

|

|

| Combination of different methods |

| ||

| Predictive models | Predictive models should be developed in order to identify patients at risk; support strategies should also be designed to prevent treatment failures in the future. (C-III) | ||

3. Predictive models

Although several authors have tried to explore the different variables that might explain non-adherence to treatment in HIV patients, not many of them set out to develop validated predictive models that could result in targeted strategies28–30. Moreover, the predictive ability of such models has so far not been optimal, with the significant heterogeneity among them hampering their widespread adoption. The differences between the models included definitions; the adherence threshold; the way adherence was measured; and the types of variables included. These predictive models have only been applied to specific patient populations and limited sample sizes.

Given the inappropriateness of classical statistical methods for analyzing large amounts of data (big data), the so-called predictive analysis has been developed, which includes techniques such as machine learning and data mining, which enable the analysis of a high number of variables in large patient cohorts and the detection of unexpected associations31. Application of his new approach to adherence to treatment of VIH infection could in the future contribute to the development of useful prediction models. A simple, easy-to-use highly sensitive and specific predictive adherence scale has been developed in our country that has shown a high negative predictive value (http://artshiv-calculator.humimar.org/es). Its generalized use, however, should be deferred until it has been evaluated in different clinical scenarios32.

III. Strategies to be used by the interdisciplinary team to improve adherenceThe following strategies have been proposed:

- 1.

Support and assistance.

- 2.

Educational, motivational and behavioral interventions.

- 3.

Regimen-related strategies.

- 4.

ICTs, LKTs, and 2.0.

- 5.

PrEP-specific strategies.

1. Support and assistance strategies

1.1. Role of the specialist physician

a) Prescription of ART and concomitant medication

It is important to individually determine when ART must be initiated and the drugs that must constitute the initial regimen, weighing the pros and cons of every alternative. Careful consideration must be given to the patients’ comorbidities, any concomitant medication and the consumption of any recreational drugs, not losing sight of potential drug-to-drug interactions. It is essential to select a regimen that is properly adapted to the patient's lifestyle and comorbidities, considering the risk of poor adherence33. Once a decision to start ART has been made, three stages must be completed: an informative stage, a consensus and engagement stage, and a maintenance and support stage.

b) Monitoring ART and the use of concomitant medication

The aging of HIV patients has increased the incidence of comorbidities not specifically related with HIV such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, renal failure, osteopenia and osteoporosis and psychiatric disorders34. This has resulted in an increase in the chronic prescription of non-antiretroviral drugs and other medications (polypharmacy). Despite polypharmacy may be warranted, its use tends to be associated with potential drug-to-drug interactions, adverse events, non-adherence, and a higher incidence of hospitalization, relapse and death. Currently, the approach to an HIV patient should go beyond treatment of the specific infection and management of the ART. It is essential to carry out a comprehensive review of the medication prescribed and the complexities of the treatment, periodically monitoring adherence to all the drugs taken by the patient and promoting a healthy lifestyle.

1.2. Role of the specialist pharmacist

One of the main priorities pharmacy consultation services focus on is adherence. In the last few years, a significant effort has gone into the development of the strategic outpatient care map and the CMO ¡capability, motivation, opportunity) model for pharmaceutical care, which have emphasized the need for pharmaceutical services to focus on each patient's individual needs35,36.

The specialist pharmacist plays a decisive role in systematic patient evaluation and improving their adherence to both ART and the other drugs part of their regimen. Specialized pharmacy guidance at the time of dispensation is an essential intervention for monitoring adherence and providing patients with the educational and behavioral support required to reinforce it37. During each consultation, the specialist pharmacist must create a privacy-preserving, trustworthy environment that facilitates communication and early identification and management of any risk factors conducive to suboptimal adherence. For the pharmacist's task to be successful, it is essential that they stratify the patients’ needs, conduct a comprehensive motivational interview and use state-of-the-art technologies that allow them to keep permanent contact with patients so as to be able to identify and resolve any issues that may potentially interfere with optimal adherence.

The pharmacist must serve as a consultant and advisor, motivating patients and offering them the information they require to make the right decisions. It is essential to build a trust-based connection so that patients feel free to share their doubts, difficulties and concerns; and design the required interventions based on the barriers identified. Motivational interviews can play an important role in this respect. During consultations, pharmacists should highlight the importance of adherence as a whole, not just to ART but also to other drugs. They should also identify potential barriers and reinforce the positive aspects of medication adherence. Lastly, they should properly monitor all their consultations38.

It is paramount to develop a stratification tool that allows identification of subgroups with different levels of risk and different pharmacy care requirements. This would allow the development of specific recommendations for each of those subgroups. Lastly, new technologies make it possible to provide periodic remote pharmacy consultations adapted to each patient's needs, monitor adherence, and assist patients with taking their medication through alerts and messaging services39,40.

Table 4 provides a summary of the goals of pharmacy consultations.

Goals of the pharmacy consultation services

| Phase | Goals |

|---|---|

| Preliminary analysis |

|

| Education/Motivation |

|

| Dispensation |

|

| Planning of next appointment |

|

ART: antiretroviral treatment.

1.3. The role of the nursing staff

The specialist nursing staff should ensure that empathy, confidentiality and respect are the building blocks of their relationship with patients. It is essential that they understand patients and their circumstances to be able to address the different factors that may interfere with proper adherence so as to improve compliance. Availability and flexibility are key qualities to promote accessibility to patients and help them connect with the multidisciplinary team taking care of them, including the staff from the HIV unit. Use of state-of-the-art technologies plays an important role in this endeavor as they facilitate permanent communication with patients. Adoption of self-care programs geared towards empowering patients is also essential. Such programs should be accompanied by behavior-changing interventions based on each patient's psychological, physical and social needs, with a view to promoting patient autonomy, engagement, responsibility and self-control42.

1.4. Role of the psychologist or psychiatrist

A psychologist can play an important role in this context by helping patients adapt to their newly diagnosed disease, considering the specific situation each of them may find themselves in. Initially, psychological interventions may contribute to adjusting the patients’ diagnosis, thereby preventing stress, anxiety or depression, which could make them neglect their health. Achievement of post-traumatic growth following a diagnosis of HIV has been associated with better adaptation and higher levels of satisfaction43.

As far as psychiatrists are concerned, their participation is fundamental when a psychiatric condition is diagnosed, whether associated to the disease requiring pharmacological monitoring or not. Unstable psychiatric patients are not in a position to achieve or maintain medication adherence. Moreover, psychiatrists should collaborate with other professionals to ensure early detection of underlying psychiatric conditions.

2. Educational, motivational and behavioral interventions

Multiple studies have looked into the impact of different intervention strategies on the improvement or maintenance of proper adherence to ART.

Table 5 provides a summary of the interventions the multidisciplinary team should carry out to improve adherence.

Summary of potential adherence-enhancing interventions by the multidisciplinary team

| Main causes of poor adherence | Potential interventions | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-related factors |

| Promoting a better understanding of the HCP/patient relationship, making it more effective. Negotiating and agreeing to a therapeutic regimen. Raising awareness about the need of undergoing treatment. Informing about the risks and benefits of treatment. Associating the administration of medication to activities of daily living. Developing techniques to boost compliance (alarms, telephones, etc.). Improving communication between HCP and patient. Providing information on the disease and its treatment, dosing rationale, risks of non-adherence. Oral and written information. Verifying proper understanding. Referring patients to psychological therapy if dysfunctions are detected, or to psychiatric services in the event of a psychiatric condition. |

| Social, economic and educational factors | Lack of social and/or family support. Low income. Low educational level. | Forging an Alliance with patient's family and friends. Understanding patient's social needs. Working with community-based organizations. Extensive education, clear and easy-to-understand explanations. |

| Treatment-related factors | Adverse events, number of daily doses. Intrusion into the patient's life. Lack of adaptation to the patient's needs and preferences. | Simplifying the therapeutic regimen. Individualizing the treatment. Comorbidities, preferences, interactions. Development of reaction mechanisms (eg. anticipation and management of adverse events). |

| Healthcare team-related factors | Lack of resources. Overcrowded and impersonal hospital environment. Lack of coordination between different support services. Inadequate educational interventions to improve adherence to ART. Lack of accessibility. Inadequate understanding of the nature of the HCP. |

|

3. Regimen-related strategies

In the last few years, most ART regimens have evolved towards regimens consisting of multiple medications in a single tablet, characterized by a pharmacokinetic profile capable of supporting a one-tablet-a-day (QD) dosage. The excellent tolerance and low toxicity of these treatments have resulted in significantly higher adherence levels.

Furthermore, patients who, for whatever reason, are prescribed more complex medication regimens may benefit from simplifying their treatment with a guarantee of full virologic suppression.

Nanotechnology opens the possibility of formulating combinations of active ingredients as nanoparticles, which allow for long-acting parenteral treatment44,45. According to the early results of some clinical trials currently under way, regimens comprising two drugs administered intramuscularly once a month or once every two months are not inferior to orally administered triple-therapy schedules. It remains to be established what kinds of patients may benefit from these regimens and to what extent adherence is likely to improve.

4. ICT, LKT and 2.0. strategies

Interventions based on digital technology are nowadays considered a useful adjunct to traditional interventions in the treatment of HIV patients. Among them, strategies like eSalud (based on the use of the internet), mSalud (based on mobile devices) or telesalud (based on ICTs) have demonstrated significant potential in the realm of adherence. Apart from recording and Table 4. Goals of the pharmacy consultation services measuring adherence, digital technology is generally believed to be capable of improving it. However, the evidence in this respect remains unclear. It is commonly considered that interventions based on mSalud, especially those using text messages or telephone calls, are the most effective. Some interventions based on videos, questionnaires or web applications have also proved useful46–48. Moreover, studies performed with specific populations have shown that users expect interventions to have a more social character, allowing interactions not only with healthcare professionals but also with peers49. In this respect, some social media-based interventions seek to create groups and communities with a view to encouraging patients to maintain proper adherence. The social media can also help monitor adherence as many patients share personal information with one another (including HIV-related and treatment-related behavior). When analyzed in an aggregate manner, such information may provide valuable data, contributing to a better understanding and more accurate predictions with respect to medication adherence50. Another possibility offered by the digital media is the implementation of online peer-to-peer programs (expert patient programs) whose ability to improve adherence has been demonstrated in some preliminary evaluations51–53.

5. Strategies intended to improve adherence to PrEP

The efficacy of PrEP is heavily dependent on high rates of adherence1. Clinical trials on the efficacy of PrEP in certain target populations, which have used different methods to measure adherence, have in some cases yielded suboptimal adherence scores, pointing to the need to develop strategies directed at increasing it54.

The strength of evidence provided by these interventions could be called into question as only a handful of clinical trials have reported on their impact. Certain cognitive-behavioral interventions piloted in the past such as counselling and individualized follow-up showed themselves to exert a positive influence on adherence55.

Qualitative studies have indicated that other strategies, such as integration of PrEP into a daily routine, the use of pillboxes, medication reminder apps, carrying the medication at all times and partner or peer support, are also somewhat effective. Depending on the specific adherence-related difficulties, one or more of the strategies above may be applied56. Text message-based interventions under the mSalud program, which enjoy wide user acceptance, have achieved high rates of effectivity, with reductions of up to 50% in missed doses54.

When prescribing PrEP, it is vital to instruct patients about the importance of making informed decisions on the use of condoms, identifying individualized strategies to maximize adherence in that respect. In the case of chemsex users, some studies have shown that adherence could be boosted by taking into account sex-enhancing and recreational drug use patterns. PrEP-related recommendations should be made in an individualized way54.

A group exhibiting a higher incidence of PrEP discontinuation is that of women, although adherent women mentioned that, apart from a personal motivation such as risk reduction and an interest in the results of research, they used adherence-enhancing strategies such as reminder apps and the support of their family members or the community54.

Before deciding on the most appropriate strategy for a specific individual, it is essential to take into consideration the different types of behaviors observed as well as each individual subject's risk of acquiring an HIV infection. Interventions should be tailored to each individual patient and should address the different barriers that may exist.

IV. Prescription, dispensation and monitoring proceduresThe time between diagnosis and the first appointment with the physician, where the patient is evaluated and their treatment is prescribed, must be short (ideally less than one week). Shortening this time improves patients’ retention of the information received, accelerates the delivery of psychological support and provides fast access to truthful information. Patients’ partners should also receive prompt attention and any supplementary studies such as blood tests, contact analysis, screening for sexually transmitted infections, etc. should be carefully planned. An agreement should be made with the patient regarding the format of future communications.

The next step is initiation of ART. Although on some occasions it could be started on day one, the guidelines recommend that ART should only be initiated once the patient is ready, which in most cases occurs after the second appointment. In any event, initiation should not be deferred longer as this would increase the risk of spreading the disease. During the first two appointments, the physician should determine whether the patient may have problems with adherence and staying in treatment33.

Medical and pharmacy appointments should be coordinated, and both professional teams should share information to avoid unnecessary visits to the hospital, i.e. promoting the idea of a “single clinical act”.

Patient with poor adherence indicators should be identified by using active alert technology based on the information, prescription and dispensation systems in place. Such information should be shared across all the staff involved to establish individualized measures capable of improving the patient's adherence. Moreover, protocols of action must be prepared for such cases, and a person in charge of coordinating the measures to be adopted should be appointed. All relevant information must be incorporated into the patient's medical record33,57.

The steps taken by the pharmacy department to improve adherence can be divided into three stages: initial assessment of the patient, therapeutic training and establishment of an individualized follow-up plan.

At the first appointment it is essential to establish a good working relationship with the patient as the latter is an essential piece to achieve the desired pharmacotherapeutic goals. The first interview should be used to garner useful information about factors that may favor or hinder such goals. Such factors may be of a socioeconomic, clinical or pharmacotherapeutic nature, or may be related to the healthcare system or the patient's degree of knowledge about their condition and the treatment to be administered.

The CMO (capability, motivation, opportunity) model for pharmaceutical care has recently been published to improve adherence in HIV patients36,58,59.

Optimizing adherence necessarily requires careful planning of physical and virtual appointments as well as the implementation of the single clinical act and new communication technologies. Dispensation should not be governed by the number of tablets included in a package but by clinical, personal and healthcare system-related aspects (appointments, distance to be traveled, etc.). In this respect, several studies recommend multi-month dispensing, taking into consideration factors like the stability of the condition, tolerance to treatment, ease of access to the healthcare facility, and time on ART, in order to make treatment more accessible, facilitate compliance and enhance the virologic response33,60.

Finally, specialized pharmacotherapeutic monitoring makes it possible to determine whether the therapeutic goals have been achieved, evaluate the safety of and adherence to the treatment administered, detect potential drug-to-drug interactions, and rectify the treatment plan, if required.

Appropriate monitoring requires that all professionals work as a multidisciplinary team so that all the information obtained at the different appointments can be shared and discussed. It is also necessary to establish an optimal circuit for managing any adverse events resulting from the treatment, as well as potential instances of non-adherence, loss of follow-up, or the need to restart treatment. Patient feedback is a valuable source of information as it allows adaptation of the monitoring program to the patients’ needs and, if required, reformulation of the pharmacotherapeutic goals. Analysis of patient-reported outcomes provides information about patients’ symptoms, functional status, health-related quality of life, wellbeing and satisfaction with the care received.

Table 6 shows the recommended interventions for each member of the multidisciplinary team.

Recommended interventions for each member of the multidisciplinary team

| Team member | Recommended interventions |

|---|---|

| Physician |

|

| Specialist pharmacist |

|

| Nursing staff |

|

| Psychologist and/or psychiatrist |

|

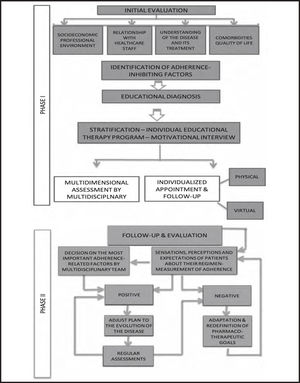

Figure 1 describes the follow-up algorithm recommended for the improvement of adherence in a multidisciplinary environment.

FundingNo funding.

Conflict of interestsNo conflict of interest.

The above authors participated in the study as representatives of the PNS-GESIDA-SEFH expert group in charge of the project. The group was made up of:

| Piedad Arazo | Department of Infectious Diseases. Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet. Zaragoza. |

| Rosa Badía | Department of Infectious Diseases. Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron. Barcelona. |

| Jordi Blanch | Department of Psychiatry and Psychology. Hospital Clínic. Barcelona. |

| Marta Cobos | External Expert. Spanish AIDS Plan. Tragsatec. |

| Jorge Elizaga Corrales | Department of Internal Medicine. General Hospital. Segovia. |

| Gabriela Fagúndez | External Expert. Spanish AIDS Plan. Tragsatec. |

| Carlos Folguera | Department of Pharmacy. Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda. Madrid. |

| Carmina R. Fumaz | Department of Infectious Diseases. Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol. Badalona. |

| Alicia Lázaro | Department of Pharmacy. University Hospital. Guadalajara. |

| Sonia Luque | Department of Pharmacy. Hospital del Mar. Barcelona. |

| Maite Martín | Department of Pharmacy. Hospital Clínic. Barcelona. |

| Emilio Monte | Department of Pharmacy. Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe. Valencia. |

| María Luisa Navarro | Department of Pediatrics. HGU Gregorio Marañón. Madrid. |

| Enrique Ortega | Department of Infectious Diseases. Consorcio Hospital General. Valencia. |

| Carmen Rodríguez | Department of Pharmacy. H.G.U. Gregorio Marañón. Madrid. |

| Javier Sánchez-Rubio | Department of Pharmacy. Hospital Universitario de Getafe. Madrid. |

| Jesús Santos González | Department of Infectious Diseases, Microbiology and Preventive Medicine. Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria. Málaga. |

| Jorge Valencia | Mobile health/social care unit; Underdirectorate General for Addictions. Madrid. |