Polypharmacy, using 6 or more medications, may increase the risk of high medication regimen complexity index (MRCI). We aimed to identify the interrelationship between trajectories of polypharmacy and MRCI.

MethodsPeople living with HIV (PLWH) (aged ≥18) were included in from 2010 to 2021. Group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM) was used to identify polypharmacy trajectories and the complexity index of the medication regimen and the dual GBTM to identify their interrelationship.

ResultsIn total, 789 participants who met the eligibility criteria were included in the study, with a median age of 47 years. GBTM analysis was used to reveal latent polypharmacy trajectories among PLWH. The findings disclosed four distinctive trajectories, with the majority (50.8%) of the PLWH falling into the ‘low increasing’ trajectory. Furthermore, GBTM identified 2 trajectories characterized by high MRCI, and a substantial proportion (80.2%) was assigned to the ‘slightly increasing low’ trajectory group. The study revealed that younger age (<50 years) was a significant predictor of membership in the ‘consistently low’ trajectory, while male gender was associated with the groups of ‘low increasing’ and ‘moderately decreasing’ polypharmacy trajectory.

ConclusionsGBTM failed to discern a discernible interrelationship between polypharmacy and the high MRCI. It is imperative to undertake future studies within this research domain, considering potential effect modifiers, notably the specific type of concomitant drug. This approach is crucial due to the outcomes induced by both polypharmacy and the magnitude of the pharmacotherapeutic complexity in PLWH.

La polifarmacia, el uso de seis o más medicamentos, puede aumentar el riesgo de un alto índice de complejidad del régimen de medicación (MRCI). Nuestro objetivo fue identificar la interrelación entre las trayectorias de polifarmacia y el MRCI.

Métodosse incluyó a personas viviendo con VIH (PVVIH) ≥18 años desde 2010 hasta 2021. Se utilizó el modelado de trayectorias basado en grupos (GBTM) para identificar las trayectorias de polifarmacia y MRCI, y para identificar su interrelación.

ResultadosEn total, se incluyeron 789 participantes que cumplían con los criterios de selección, con una edad mediana de 47 años. El análisis GBTM se utilizó para revelar trayectorias de polifarmacia latentes entre PVVIH. Los hallazgos revelaron cuatro trayectorias, con la mayoría (50,8%) de PVVIH ubicadas en la trayectoria de «aumento bajo». Además, GBTM identificó dos trayectorias caracterizadas por MRCI altos, y una proporción sustancial (80,2%) se asignó al grupo de trayectoria de ‘aumento ligeramente bajo’. El estudio reveló que una edad más joven (<50 años) fue predictor significativo de pertenencia a la trayectoria ‘bajo constante’, mientras que el género masculino se asoció con las trayectorias de polifarmacia ‘aumento bajo’ y ‘disminución moderada’.

ConclusionesEl GBTM no logró discernir una interrelación entre polifarmacia y alto MRCI. Es fundamental llevar a cabo futuros estudios en este ámbito, considerando modificadores de efecto potenciales, especialmente el tipo de medicamento concomitante. Este enfoque es crucial debido a los resultados inducidos tanto por la polifarmacia como por la magnitud de la complejidad farmacoterapéutica en las PVVIH.

In Spain, it is estimated that at the end of 2022 approximately 90 000 people were HIV positive.1 In developed countries, 30% of people living with HIV (PLWH) are currently 50 years of age or older. There are already studies that estimate that by 2030 approximately 75% of global HIV patients will be 50 years old and around 40% will be 65 years or older.2

These findings stem from advancements in antiretroviral (ARV) medications, which have enhanced efficacy and safety. Consequently, there has been a decrease in mortality among PLWH, with their life expectancy now comparable to that of seronegative population.3,4 The aging of PLWH reveals new challenges in their healthcare, which is becoming more complex due to the increase in the prevalence of age-related comorbidities and even the appearance of multimorbidity patterns.5,6

This scenario implies an increase in the prevalence of polypharmacy, aimed at the management of these concurrent comorbidities.7 The negative effects that polypharmacy can have on patients, such as lack of adherence, interactions, or toxicity associated with drugs, are known.8

Traditionally, the approach to measuring polypharmacy has been quantitative, that is, based on the number of prescribed medications. However, in recent years, a more qualitative approach has been used, as the same number of drugs can differ in aspects such as administration instructions, preparation or administration methods, pharmaceutical formulation, or dosage regimen. George et al. introduced the ‘Medication Regimen Complexity Index’ (MRCI), which allows the consolidation and weighting of all these factors.9 In this sense, a threshold value of 11.25 has been established for this index as a benchmark for classifying a polypharmacy patient as having high complexity in the context of PLWH.10

Static measures, like cross-sectional studies examining the proportion of polymedicated patients or those with MRCI values exceeding 11.25, are commonly used to analyzed polypharmacy and pharmacotherapeutic complexity. However, these approaches do not capture the dynamic nature of these phenomena over time, influenced by various changing factors. Group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM) is a data-driven statistical method used to analyzed developmental trajectories, representing the evolution of an outcome with age or time.11 This methodology has been used to analyze drug adherence and polypharmacy in both the general population and HIV patients. Identifying individuals with high MRCI trajectories is crucial for developing tailored interventions and strategies.12,13 Multiple characteristics influencing patients with elevated pharmacotherapeutic complexity may be more relevant for detection than singular risk factors. Compared to conventional methods that rely on dichotomized cut-off points and specific time points to determine MRCI levels, GBTM can predict treatment outcomes with temporal trends from onset to patient care, offering more comprehensive insights into patient management.11 To our knowledge, only one study has utilized this methodology to analyzed polypharmacy and adherence.

The research objective is to utilize GBTM analysis to identify distinct trajectories of pharmacotherapeutic complexity and polypharmacy among PLWH. By examining the associations between identified trajectories and levels of pharmacotherapeutic complexity within the context of polypharmacy, the research aims to provide valuable insights for personalized healthcare approaches and targeted interventions to optimize medication management for PLWH.

MethodsStudy design, participants, and ethics issuesWe performed a retrospective analysis of the longitudinal data of PLWH from a hospital center between January 2010 and December 2021. Patients ≥18 years on active ARV and a minimum of 3 pharmacotherapeutic follow-up visits per year were enrolled. Patients were excluded if they participated in a clinical trial.

The study met all ethical requirements and was approved by the Sevilla-Sur Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Sevilla-Sur (C.I. 1341-N-23). This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines for biomedical research.

Data collectionData recorded were demographic, HIV-infection-related data, and clinical variables related to comorbidities. Pharmacotherapeutic history data were collected from medical records, electronic prescription program, outpatient dispensing program, and patient interviews.

Polypharmacy was defined as the concurrent use of 6 or more drugs, including both ARV and medications that are available by prescription as well as those that are sold over the counter without a prescription. To delineate the patterns of polypharmacy, we utilized Calderón-Larrañaga et al.'s classification, which categorizes patterns based on medications targeting specific medical conditions. An individual was categorized into a polypharmacy pattern if they were prescribed at least three medications associated with that particular pattern.15 Major polypharmacy was defined as the concurrent use of 10 or more co-medications apart from ARV.

MRCI was a validated tool composed of 65 individual components and was developed to assess the complexity of a treatment regimen. These elements encompass various aspects, including the number of medications, the form of dosage, the frequency of dosing, and any supplementary or specific instructions related to the regimen. The MRCI index evaluative scale ranges from 1.5, representing a single tablet or capsule taken once a day, to an open upper limit that increases proportionally with the increase in the number of prescribed drugs. A higher value on the MRCI index denotes a higher level of complexity of the treatment.9 Consistent with the study by Morillo-Verdugo et al., a cut-off value of 11.25 was used for the MRCI index score to identify patients undergoing complex treatment regimens.10

Comorbidity referred to any persistent medical condition that existed in the patient at the beginning of the study or emerged during the duration of the study. The registry of comorbidities relied on chronic conditions that were self-reported by patients and diagnosed by physicians. The classification of comorbidity patterns was also aligned with the categorization method outlined in the publication by De Francesco et al.16

Statistical analysisElbur et al.'s methodology was adopted to analyze polypharmacy and MRCI in PLWH.14 The process began with GBTM, classifying participants into groups based on polypharmacy and pharmacotherapeutic complexity using censored normal and logit models. Iterative model fitting determined the optimal number and shapes of these groups.

The final stage involved estimating a dual-trajectory model integrating univariate models, assessing dependencies between polypharmacy and pharmacotherapeutic complexity through conditional and joint probabilities. Elbur et al.'s polypharmacy trajectory nomenclature was used for standardization and clarity.

Model fit was evaluated using Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), with lower values indicating a better fit. Adequate classification accuracy was indicated by mean posterior probabilities above 0.70, and groups had to represent at least 5% of the sample size. Confidence intervals around group membership probabilities had to be tight, and statistical significance was required (p<.05).

Descriptive statistics for polypharmacy trajectories and MRCI were presented as counts, percentages, median, and interquartile range (IQR). Chi-square tests compared distributions across polypharmacy trajectories, while Pearson correlation assessed the association between polypharmacy and pharmacotherapeutic complexity over the study period.

To identify predictors of high pharmacotherapeutic complexity, multinomial logistic regression adjusted for relevant variables was used. The group with the highest probability of high complexity served as the reference category. Variables with p-values <.25 in uni- and covariate analyses were considered for the final regression model.

Data analysis was conducted using Stata version 16, incorporating a plugin for estimating GBTM parameters.

Analysis groups- 1

Polypharmacy group: These groups comprise participants who meet the criteria for both polypharmacy and major polypharmacy. Through the application of GBTM using a censored normal model, participants were identified and categorized into different trajectory groups.

- 2

Medication Regimen complexity Index group: These groups are composed of participants with a MRCI value greater than 11.25. Using GBTM with a logit model, participants will be categorized into trajectory groups based on their complexity index.

Overall, 792 patients were followed during the study period. Three PLWH were lost to follow-up. Two patients were lost due to a change in hospital center, and one patient was lost due to discontinuation of follow-up. Consequently, 789 PLWH participated in the analysis. At the time of the initial visit, the median age of the participants was 47 (IQR: 41–51) years and the majority (81.5%) were men. Most of the PLWHs were virologically suppressed (84.3%) and 90.1% of the patients had a CD4 cell count greater than 200 cells/μL. All PLWHs were on active ARV and more than half of the patients were taking non-HIV medications (65.8%). However, the number of polymedicated patients reaches only 11.5%. According to MRCI data, 16.6% of PLWH were classified as complex patients according to the MRCI value greater than 11.25.

Average trend and association of polypharmacy and high MRCI during the study periodFig. 1a and b shows trends in the percentages of polymedicated PLWH and patients with an MRCI value greater than 11.25 in each year of follow-up. No linear trends were observed in polypharmacy or in PLWH with MRCI value greater than 11.25 during the study period. The overall correlation between polypharmacy patients and those defined as complex based on the value of MRCI during the study period was 0.789 (p<.01).

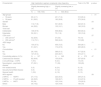

Trajectories of polypharmacyFirst, it was carried out considering the general treatments prescribed and over the counter drugs. GBTM identified four latent polypharmacy trajectories that were called ‘consistently high’ (N=92; 11.7%), ‘moderately decreasing’ (N=40; 5.1%), ‘low increasing’ (N=401; 50.8%), and ‘consistently low’ (N=256; 32.5%), as shown in Fig. 2. The polypharmacy patterns of the ‘consistently high’, ‘low increasing’, and ‘consistently low’ groups remained largely steady. Table 1 shows the characteristics at the beginning of the present study based on polypharmacy, considering the general trajectories of drug use.

Characteristics of PLWH based in polypharmacy groups at baseline (all medicaments).

| Characteristic | Polypharmacy trajectory | Total; n (%) N=789 | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistently high; n (%) | Moderate decreasing; n (%) | Low increasing; n (%) | Consistently low; n (%) | |||

| N=92 (11.7) | N=40 (5.1) | N=401 (50.8) | N=256 (32.5) | |||

| Age groups | <.01 | |||||

| <50 years | 44 (47.8) | 23 (57.5) | 223 (55.6) | 191 (74.6) | 481 (61) | |

| ≥50 years | 50 (54.2) | 15 (42.5) | 178 (44.4) | 65 (25.4) | 308 (39) | |

| Gender | .04 | |||||

| Male | 84 (91.3) | 29 (72.5) | 319 (79.6) | 210 (82) | 642 (81.4) | |

| Women | 8 (8.7) | 11 (27.5) | 82 (20.4) | 46 (18) | 147 (18.6) | |

| Viral load | .17 | |||||

| Indetectable | 79 (85.9) | 31 (77.5) | 326 (81.3) | 221 (86.3) | 657 (83.3) | |

| Detectable | 13 (14.1) | 9 (22.5) | 75 (18.7) | 35 (13.7) | 132 (16.7) | |

| CD4 count | .07 | |||||

| <200 cell/mm3 | 10 (10.9) | 5 (12.5) | 55 (13.7) | 19 (7.4) | 89 (11.3) | |

| ≥200 cell/mm3 | 82 (89.1) | 35 (87.5) | 346 (86.3) | 237 (92.6) | 700 (88.7) | |

| AIDS stage | <.01 | |||||

| No | 57 (62) | 21 (52.5) | 251 (62.6) | 192 (75) | 521 (66) | |

| Yes | 35 (38) | 19 (47.5) | 150 (37.4) | 64 (25) | 268 (44) | |

| Comorbidities | <.01 | |||||

| No | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.5) | 125 (31.2) | 191 (74.6) | 318 (40.3) | |

| Yes | 91 (98.9) | 39 (97.5) | 276 (68.8) | 65 (25.4) | 471 (59.7) | |

| Comorbidity patterns; N (%) | N=91 | N=39 | N=276 | N=65 | N=471 | .04 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 54 (59.3) | 23 (59) | 150 (54.3) | 50 (77) | 277 (58.9) | |

| Liver pathology – COPD | 7 (7.7) | 1 (2.6) | 17 (6.2) | 2 (3.1) | 27 (5.7) | |

| Neurological-psychiatric disease | 30 (33) | 14 (35.9) | 97 (35.1) | 10 (15.4) | 151 (32.1) | |

| HIV-related events | 0 | 0 | 9 (3.3) | 1 (1.5) | 10 (2.1) | |

| Sexually transmitted disease | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.7) | 1 (1.5) | 3 (0.6) | |

| General health | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.5) | 3 (0.6) | |

| ARV regimen | .13 | |||||

| 2 NRTIs+NNRTI | 19 (20.7) | 8 (20.5) | 120 (29.9) | 92 (35.9) | 239 (30.3) | |

| 2 NRTIs+PI with boosted | 31 (33.7) | 15 (37.5) | 101 (25.3) | 66 (25.8) | 213 (27) | |

| 2 NRTIs+INSTI | 20 (21.7) | 7 (17.5) | 92 (22.9) | 43 (16.8) | 162 (20.5) | |

| Others | 22 (23.9) | 10 (24.5) | 88 (21.9) | 55 (21.5) | 175 (22.2) | |

The choice of the 4-variable model in polypharmacy is justified because, despite the lower BIC of models with fewer variables, it offers a better understanding of complex clinical and demographic relationships, crucial for managing HIV patients. This choice is also supported by consistent literature citing 4 polypharmacy trajectories, providing more detailed insights into polypharmacy trajectories.

Trajectories of high MRCIConsidering patients with a pharmacotherapeutic complexity index equal to or greater than 11.25, GBTM identified 2 complexity trajectories that can be defined as ‘slightly decreasing high’ (N=156; 19.8%) and ‘slightly increasing low’ (N=633; 80.2%), as shown in Fig. 3. Table 2 shows the characteristics at the start of the current study by the high complexity index of the medication regimen trajectories.

Characteristics of PLWH based in medication regimen complexity index trajectory groups at baseline.

| Characteristic | High medication regimen complexity index trajectory | Total n (%) 789 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slightly decreasing high; n (%) | Slightly increasing low; n (%) | |||

| N=156 (19.8) | N=633 (80.2) | |||

| Age groups | <.01 | |||

| <50 years | 65 (41.7) | 451 (71.2) | 516 (65.4) | |

| ≥50 years | 91 (58.3) | 182 (28.8) | 273 (34.6) | |

| Gender | .03 | |||

| Male | 112 (71.8) | 531 (83.9) | 643 (81.5) | |

| Women | 44 (28.2) | 102 (16.1) | 146 (18.5) | |

| Viral load | .59 | |||

| Indetectable | 106 (67.9) | 558 (88.2) | 664 (84.2) | |

| Detectable | 50 (32.1) | 75 (11.8) | 125 (15.8) | |

| CD4 count | .57 | |||

| <200 cell/mm3 | 42 (26.9) | 37 (5.8) | 79 (10) | |

| ≥200 cell/mm3 | 114 (73.1) | 596 (94.2) | 710 (89) | |

| AIDS stage | .11 | |||

| No | 105 (67.3) | 459 (72.5) | 564 (89.1) | |

| Yes | 51 (32.7) | 174 (27.5) | 225 (28.5) | |

| Comorbidities | <.01 | |||

| No | 29 (18.6) | 388 (61.3) | 417 (52.9) | |

| Yes | 127 (81.4) | 245 (38.7) | 372 (47.1) | |

| Comorbidity patterns; N (%) | N=127 | N=245 | N=372 | .47 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 82 (64.6) | 155 (63.4) | 237 (63.8) | |

| Liver pathology – COPD | 7 (5.5) | 6 (2.4) | 13 (3.5) | |

| Neurological – psychiatric disease | 37 (29.1) | 71 (29) | 108 (29) | |

| HIV-related events | 0 (0) | 6 (2.4) | 6 (1.6) | |

| Sexually transmitted disease | 0 (0) | 3 (1.2) | 3 (0.8) | |

| General health | 1 (0.8) | 4 (1.6) | 5 (1.3) | |

| ARV regimen | .09 | |||

| 2 NRTIs+NNRTI | 27 (17.3) | 222 (35.3) | 249 (31.5) | |

| 2 NRTIs+PI with boosted | 46 (29.5) | 168 (26.7) | 214 (27.2) | |

| 2 NRTIs+INSTI | 53 (34) | 123 (19.4) | 176 (22.3) | |

| Others | 30 (19.2) | 120 (18.6) | 150 (19) | |

In the joint model, the optimal number of groups identified in the univariate analysis for each variable was determined (Table 1, supplementary material). The findings indicated slight changes in the probabilities of group membership when contrasting the univariate and dual models for the polypharmacy trajectories, except for instances characterized by moderately decreasing and low increasing values (Table 2a, supplementary material). The probabilities of group membership were also calculated while comparing the univariate and dual models for the trajectories of a high MRCI (Table 2b, supplementary material).

Interrelationships between the polypharmacy trajectory groups and high complexity according to the MRCITable 3a of supplementary material showed the probability of belonging to the trajectory groups in polypharmacy based on the trajectory of a high complexity index of a MRCI. The results show that PLWH in the group of the complexity index of the medication regimen ‘slightly decreasing high’ mostly included the polypharmacy categories ‘consistently high’ followed by ‘moderately decreasing’. As expected, most of the members included in the ‘slightly increasing low’ high pharmacotherapeutic complexity trajectory group were in the ‘consistently low’ polypharmacy group.

Table 3b of supplementary material showed the probability of membership of the trajectory group in the high MRCI conditional on the polypharmacy groups. The analysis shows results in line with the previous table, finding that the polypharmacy groups ‘consistently high’ and ‘moderately decreasing’ constituted the highest percentages within the high medication regimen complexity index ‘Slightly decreasing high’ group with 56% and 37%, respectively. Similarly, in the high medication regimen complexity index group ‘slightly increasing low’, the polypharmacy groups ‘consistently low’ (64%), and ‘low increasing’ (34%) had a higher percentage.

Predictors of group membership in high-complexity index medication regimen trajectoriesTable 3 shows the predictors of group membership for each polypharmacy path compared to the ‘consistently high’ polypharmacy group in the multivariate multinomial model. The results showed that significant predictors of being a member of the ‘consistently low’ trajectory were younger age <50 years. Additionally, male gender was identified as a predictor of ‘low increasing’ and ‘moderately decreasing’.

Predictors of group membership in polypharmacy trajectories compared to the reference group consistently high polypharmacy.

| Covariates | Consistently low (n=256) aOR (95% CI) | Low increasing (n=401) aOR (95% CI) | Moderate decreasing (n=40) aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Women | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 0.8 (0.3–2.5) | 0.4 (0.1–0.9)* | 0.2 (0.1–0.6)* |

| Age groups | |||

| ≥50 years | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| <50 years | 2.2 (1.1–4.2)* | 1.2 (0.7–2.3) | 1.5 (0.7–3.0) |

| AIDS stage | |||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 1.2 (0.6–2.2) | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) |

| CD4 count | |||

| ≥200 cell/mm3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| <200 cell/mm3 | 0.2 (0.1–1) | 1.3 (0.5–3.4) | 0.8 (0.3–1.3) |

| Viral load | |||

| Detectable | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Indetectable | 0.6 (0.2–1.5) | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 0.5 (0.2–1.5) |

| ARV regimen | |||

| Others | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 NRTIs+NNRTI | 1.2 (0.5–3.0) | 1.3 (0.6–3.0) | 0.8 (0.3–2.2) |

| 2 NRTIs+PI with boosted | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | 0.7 (0.3–1.9) |

| 2 NRTIs+INSTI | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) | 1.1 (0.5–2.7) | 0.8 (0.3–2.3) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 0.3 (0.1–4.8) | 0.03 (0.01–0.2)* | 0.9 (0.1–14.1) |

*p-value <.05.

Abbreviation: aOR-adjusted odds ratio.

Our analysis revealed 4 polypharmacy trajectories, with the ‘low increasing’ group representing the largest proportion of PLWH (50.8%). Considering patients with a high level of pharmacotherapeutic complexity (MRCI value ≥11.25), GBTM identified 2 trajectories, with 80.2% in the ‘low increasing’ polypharmacy trajectory group. The joint model did not reveal any apparent relationship between the polypharmacy trajectories and the high pharmacotherapeutic complexity.

In the current analysis, GBTM provided a unique perspective on the changing nature of polypharmacy behavior in PLWH, differentiating 4 categories. There are different previous studies that analyzed the polypharmacy trajectories in a specific sex. One of them analyzed both adherence and polypharmacy in women with HIV in the United States. As in our case, 4 polypharmacy trajectories were distinguished. As in our study, the largest proportion of these HIV-infected women were in the ‘low increasing’ polypharmacy trajectory group. There is a higher percentage of men with HIV infection in the ‘consistently high’ and ‘consistently low’ polypharmacy category groups. Furthermore, the study by Ware et al., who used GBTM to examine polypharmacy among HIV-infected men in the MACS cohort, was significant. Four groups were identified, with 48% of participants in a non-polypharmacy group.17 This study finds that PLWH and over 50 years of age are associated with polypharmacy trajectory groups, as in our study where the polypharmacy trajectory ‘consistently high’ presents a higher percentage of PLWH over 50 years of age.

A population-based study in Spain analyzed 23 000 individuals with HIV, revealing a higher prevalence of polypharmacy among women (45%) compared to men (30%).18 Contrarily, our study demonstrates a higher prevalence of polypharmacy in men compared to women across all polypharmacy trajectories, as shown in Table 1. This discrepancy may be due to higher rates of chronic diseases in women.19 Notably, our study finds cardiovascular disease-related comorbidities more prevalent among males, aligning with findings by Camps-Vilaró et al.20 The ‘moderately decreasing’ group under 50 years experiencing reduced drug load is often associated with psychiatric–neurological conditions, particularly anxiety and depression.21 This phenomenon in PLWH under 50 years of age can be explained by the development of neuropsychiatric disorders that may be related to the diagnosis of HIV infection and the associated stigma.

In general, the results revealed that the predictor of belonging to the consistently low polypharmacy path was patients under 50 years of age. All this is widely described at the bibliographic level, since HIV patients older than 50 years suffer a subclinical chronic inflammatory process that is associated with the development of age-related comorbidities and, therefore, the prescription of medications to control these chronic diseases.22,23 However, the protective nature of the male sex stands out in the ‘low increasing’ and ‘consistently low’ polypharmacy trajectories. This is related to the higher prevalence of polypharmacy shown by women, as described in different studies.24,25

In this analysis, GBTM provided a novel perspective on high pharmacotherapeutic complexity previously unexplored. Prior research has highlighted the significance of pharmacotherapeutic complexity in health-related outcomes, linking elevated complexity to reduced patient-perceived quality of life and adverse health outcomes, such as mortality, particularly among elderly patients.26,27 The findings demonstrated the statistical significance of belonging to the ‘slightly decreasing high’ trajectory of high pharmacotherapeutic complexity, especially for PLWH under 50 years with comorbidities. This trajectory is associated with polypharmacy trajectories like ‘consistently high’ and ‘moderately decreasing’, described in existing literature as being due to age-related comorbidities.22 Categorizing PLWH based on their high-pharmacotherapeutic complexity trajectories can offer new insights into patient identification and help develop strategies to enhance health outcomes.

The interplay between polypharmacy and high pharmacotherapeutic complexity may entail an increased risk of adverse effects, drug interactions, and heightened challenges in patient treatment management and adherence. Additionally, it may necessitate closer monitoring and enhanced multidisciplinary collaboration to optimize the safety and efficacy of treatment.

It is already known that polypharmacy has a positive correlation with pharmacotherapeutic complexity. However, contrary to our hypothesis, the primary analyses did not reveal any interrelationship between the polypharmacy groups and the high-medical regimen complexity index trajectory groups. A potential explanation for our findings could be the presence of an effect modifier between polypharmacy and high MRCI, such as the therapeutic group of the patients' concomitant medication to ARV. There is a study of elderly patients with chronic kidney disease that shows the influence of the pharmacotherapeutic group of the treatment on the pharmacotherapeutic complexity, finding that in this population phosphate binders were associated with more-complex medication regimens.28

This methodology offers new research avenues to explore interrelationships among various effects, facilitating the identification of modifying variants. This knowledge can inform targeted intervention strategies aimed at controlling these effects. Specifically, it enables the development of deprescribing strategies to reduce MRCI values, thereby promoting optimal health outcomes, including improved quality of life.

The findings of this analysis show the importance of evaluating PLWH in the ‘consistently high’ and ‘moderately decreasing’ polypharmacy trajectories due to the association of this effect with the prescription of potentially inappropriate drugs and negative effects associated with polypharmacy, such as interactions.29,30 Interventions such as deprescribing should be implemented, making it possible to address both polypharmacy and reduce the pharmacotherapeutic complexity of the patient.

Strengths of this analysis include the large sample size of PLWH who were followed for an extended period, allowing the model to identify the trajectories of both variables.

Despite these results, one of its several limitations must be highlighted. It is a single-center cohort study and hence the possibility that the trajectories cannot be generalized to other HIV populations. This could be explained by the deprescription and pharmacotherapy optimization programs presented by each center, which reduces both the prevalence of polymedicated patients and those with high pharmacotherapeutic complexity. Finally, despite the sample size included, there is the possibility of losing patients to follow-up over time due to changing centers or abandoning treatment, which is a potential limitation that should be considered.

In conclusion, dual GBTM did not identify an interrelationship between polypharmacy and high MRCI. It is crucial to conduct future studies in this line of research, considering potential effect modifiers such as the type of concomitant drug, due to the outcomes induced by both polypharmacy and the value of MRCI in PLWH.

Contribution to Scientific LiteratureThis study utilizes GBTM to examine polypharmacy and medication regimen complexity among PLWH. It identifies distinct polypharmacy trajectories, including a notable ‘low increasing’ pattern, and identifies trajectories characterized by higher MRCI.

These findings underscore the complex relationship between polypharmacy and medication complexity in PLWH. Age and gender were identified as factors influencing polypharmacy trajectories, highlighting the need for tailored therapeutic approaches. Further research into the specific impacts of medications on treatment outcomes is crucial for optimizing HIV management strategies in clinical practice.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant funding from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.

Ethical considerationsThe study complied with all ethical requirements and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Seville-South (C.I. 1341-N-23). This study was conducted in accordance accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki for biomedical research.

Transparency statementThe author for the correspondence, on behalf of the other signatories, guarantees the accuracy, transparency, and honesty of the data and information contained in the study; that no relevant information has been omitted; and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

CRediT authorship contribution statementEnrique Contreras Macías: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. María de las Aguas Robustillo Cortés: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Ramón Morillo Verdugo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.