Endometrial cancer with microsatellite instability (MSI) involves 30% of diagnosed cases. There are some uncertainty about second-line treatment, after platinum-based first-line treatment. The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review on the scientific evidence of immunotherapies for endometrial cancer with MSI.

MethodsPubMed and Embase databases were searched up to May 28, 2024. We included clinical trials about patients with mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) or high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) diagnosed with advanced and/or metastatic endometrial cancer who had previously received platinum-based chemotherapy. Clinical trials with a dMMR or MSI-H population size of less than 10 patients were discarded. Efficacy results in overall survival, progression-free survival and objective response rate were used to determine the most interesting drugs. A safety analysis of therapies was developed.

ResultsFifty-four studies were found in a systematic search. Fourteen clinical trials were selected. The following drugs were evaluated: pembrolizumab monotherapy, pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib, durvalumab, durvalumab-tremelimumab combination, dostarlimab, nivolumab and avelumab. The greatest numerical efficacy effect was achieved by pembrolizumab, followed by pembrolizumab in combination with lenvatinib. The most common adverse events were fatigue and gastrointestinal disorders.

ConclusionThe efficacy of pembrolizumab and pembrolizumab-lenvatinib regimen appears promising. However, studies with larger sample size, longer follow-up and comparative design with subgroup analysis based on differences in microsatellite repair mechanisms are needed for proper therapeutic positioning.

El cáncer de endometrio con inestabilidad de microsatélites (MSI) representa el 30% de casos diagnosticados. Existe incertidumbre sobre el tratamiento de segunda línea, tras una primera línea basada en platino. El objetivo de este estudio fue realizar una revisión sistemática sobre la evidencia científica de los tratamientos inmunoterápicos para el cáncer de endometrio con MSI.

MétodosSe realizó una búsqueda en la base de datos PubMed y Embase hasta el 28 de mayo de 2024. Se incluyeron ensayos clínicos con pacientes que presentasen deficiencia de reparación de emparejamientos erróneos (dMMR) o alta inestabilidad de microsatélites (MSI-H) diagnosticados de cáncer de endometrio avanzado y/o metastásico que habían recibido previamente quimioterapia basada en platino. Se descartaron los ensayos clínicos con un tamaño de población de dMMR o MSI-H inferior a 10 pacientes. Para determinar los fármacos de mayor interés se emplearon los resultados de eficacia en supervivencia global, supervivencia libre de progresión y tasa de respuesta objetiva. Se realizó un análisis sobre la seguridad de las terapias.

ResultadosSe encontraron 54 estudios, de los cuales 14 ensayos clínicos fueron incluidos. Los siguientes fármacos fueron evaluados: pembrolizumab en monoterapia, pembrolizumab más lenvatinib, durvalumab, durvalumab en combinación con tremelimumab, dostarlimab, nivolumab y avelumab. El mayor efecto numérico en eficacia se alcanzó con pembrolizumab, seguido de pembrolizumab en combinación con lenvatinib. Los eventos adversos más frecuentes fueron fatiga y alteraciones gastrointestinales.

ConclusionesLa eficacia de pembrolizumab y del régimen pembrolizumab-lenvatinib parece prometedora. Sin embargo, son necesarios estudios con mayor tamaño muestral, seguimiento más prolongado y diseño comparativo con análisis de subgrupos basado en diferencias en los mecanismos de reparación de microsatélites para un posicionamiento terapéutico adecuado.

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the sixth most common neoplasm diagnosed in women. This pathology caused 97,000 deaths worldwide in 2020.1 Some cases of EC have been associated with microsatellite instability (MSI). The prevalence of MSI in EC is estimated to be around 30% of diagnosed cases.2

The mechanism of microsatellite (MS) generation could be explained by DNA displacement during replication, or by a mismatch between the coding strand and the template strand during replication and repair process. This would result in the erroneous addition or deletion of one or more base pairs.3 Mismatch repair (MMR) system –one of DNA repair mechanisms in healthy cells– maintains the number of MS repeats at every cell division. Deficiencies in MMR prevent cells from regulating these sequences and MSI are originated.3,4 Absence of one or more MMR proteins (MSH2, MSH6, MLH1 and PMS2) results in an MMR deficiency (dMMR). According to the frequency of error production, three types of MSI are distinguished: high MSI (MSI-H), low MSI (MSI-L) and MS stability (MSS).3 On the other hand, the presence of all MMR proteins confers a competent system (MMRp).5 A significant proportion of MSI-H tumours present dMMR, whereas those characterised as MSI-L appear to manifest MMRp. Some studies suggest that tumours with MSI-L or MSS features do not differ in their molecular or physiological characterisation.6,7

Molecular investigation of genetic defects has allowed the differentiation of another gene related to MS, whose mutation leads to high error accumulation. Disruptions in exonuclease domain of polymerase ɛ (POLE) gene are associated with MSI-H.3

To date, platinum-based chemotherapy has been a common first-line treatment in advanced EC.8 On the other hand, EC characterised by the presence of MSI has been associated with increased neoantigen load and increased CD3(+), CD8(+) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) in tumour infiltrating lymphocytes compared to EC with MSS.9 Likewise, increased expression of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) has been observed in intraepithelial immune cells of MSI tumours. These findings have led to the use of therapies targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibition in the treatment of EC with MSI. The aim of this work was to develop a systematic review of literature on the scientific evidence of immunotherapeutic drugs for EC with MSI previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy.

MethodsLiterature search and study selectionPICOS model was applied to perform the literature search: patients, intervention, comparator, objective and study design.10 Patients with dMMR or MSI-H diagnosed with advanced and/or metastatic EC who had previously received platinum-based chemotherapy were selected. All immunotherapies used as intervention and all comparators were included. Selected endpoints were objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). In terms of design, clinical trials (CTs) with a minimum of 10 target patients were included. Conference communications were excluded due to a lack of information.

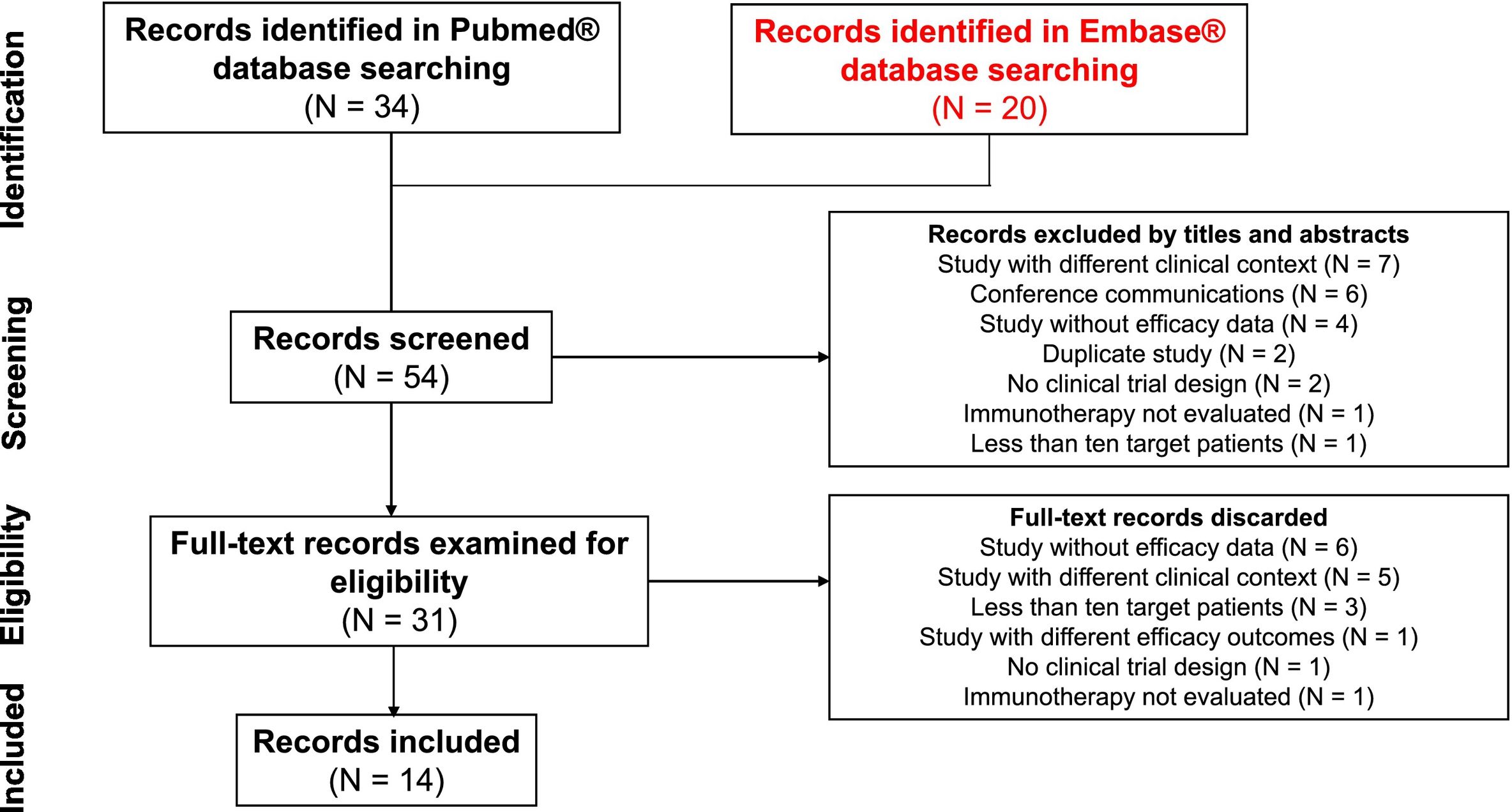

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)11 methodology was used to conduct a review in PubMed® and Embase® databases up to 28 May 2024. Filter ‘clinical trials’ was applied with the following terms: [microsatellite instability OR mismatch repair deficient] AND endometrial cancer. “PICO tool” was used on the Embase® database according to the PICOS model described above. The following search criteria were applied in Embase® database: (‘endometrium cancer’/exp. AND ‘microsatellite instability’ OR ‘mismatch repair deficient’/exp) AND ‘immunotherapy’/exp. AND (‘objective response rate’/exp. OR ‘progression free survival’/exp. OR ‘overall survival’/exp) AND ‘clinical trial’/exp. AND [<1966–2024]/py.

Two investigators conducted the search independently. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between study authors. Titles and abstracts were screened to exclude results that did not meet the study inclusion criteria. Full articles were reviewed in the eligibility process. Studies were accepted in English or Spanish.

Data extractionData from all studies were extracted and validated by two investigators. The following variables were collected from trials: authors and publication dates, study design, histology, stage, treatment lines, median follow-up, number of patients, treatments used as intervention and control. For efficacy endpoints, ORR values, median PFS and OS, confidence intervals and relative values in comparative CTs were collected. Regarding safety, the most frequent adverse events (AEs) of any grade, those of grade 3 or higher and immune-mediated AEs were recorded. Treatment reductions, discontinuations and deaths due to AEs were also obtained in those studies where available.

Data analysisImportance of outcomes was assigned on the basis of clinical relevance for analysis of the efficacy of therapeutic alternatives. Final endpoint considered most important was OS (time from randomisation to death from any cause). PFS (time from randomisation to progression or death from any cause) was established as the surrogate endpoint of greatest value. ORR, defined as the proportion of patients with partial or complete response according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) criteria version 1.1,12 was analysed as the least relevant surrogate endpoint. The most interesting therapeutic alternatives were determined based on the above-mentioned efficacy criteria.

In terms of safety, AEs were assessed in patients who had received at least one dose of the drug during CT. AEs of grade 3 or higher were considered the most important due to their difficult management. The most frequent AEs (regardless of grade) and immune-mediated AEs were checked. Other data such as reductions, discontinuations or deaths due to treatment were reviewed.

The selected studies were grouped according to the treatment regimens used.

Risk of biasAvailability of exclusive data on the target population (advanced and/or metastatic EC who had previously received platinum-based chemotherapy) or subgroup analyses were evaluated. Quality of data from the target population (previously treated patients) is superior to the quality of results from populations involving patients from different lines of treatment. Inappropriate interpretations of aggregate data could influence the conclusions. Sample sizes of CTs and follow-up periods were also checked. More reliable results are obtained from large sample sizes and long follow-up periods. Adequate sample sizes and patient follow-ups allow minimising unrealistic dispersion of results, as well as determining an acceptable number of events.

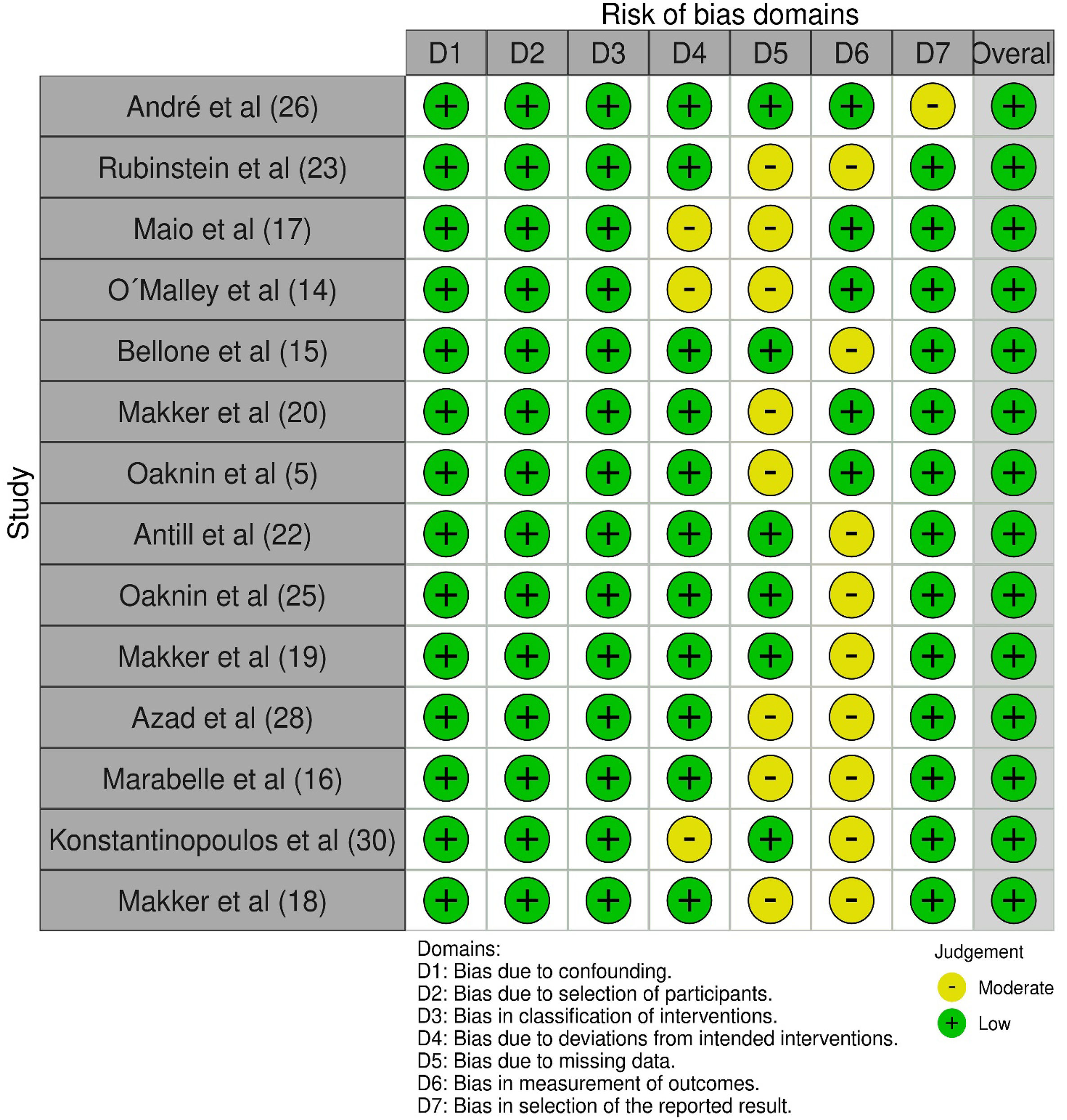

Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool was applied to the included studies,13 including eight domains: confounding bias; selection of participants into the study (or into the analysis) bias; classification of interventions bias; deviations from intended interventions bias; missing data bias; measure the outcome bias; selection of the reported results; and overall bias. Two investigators independently assessed the risk of bias.

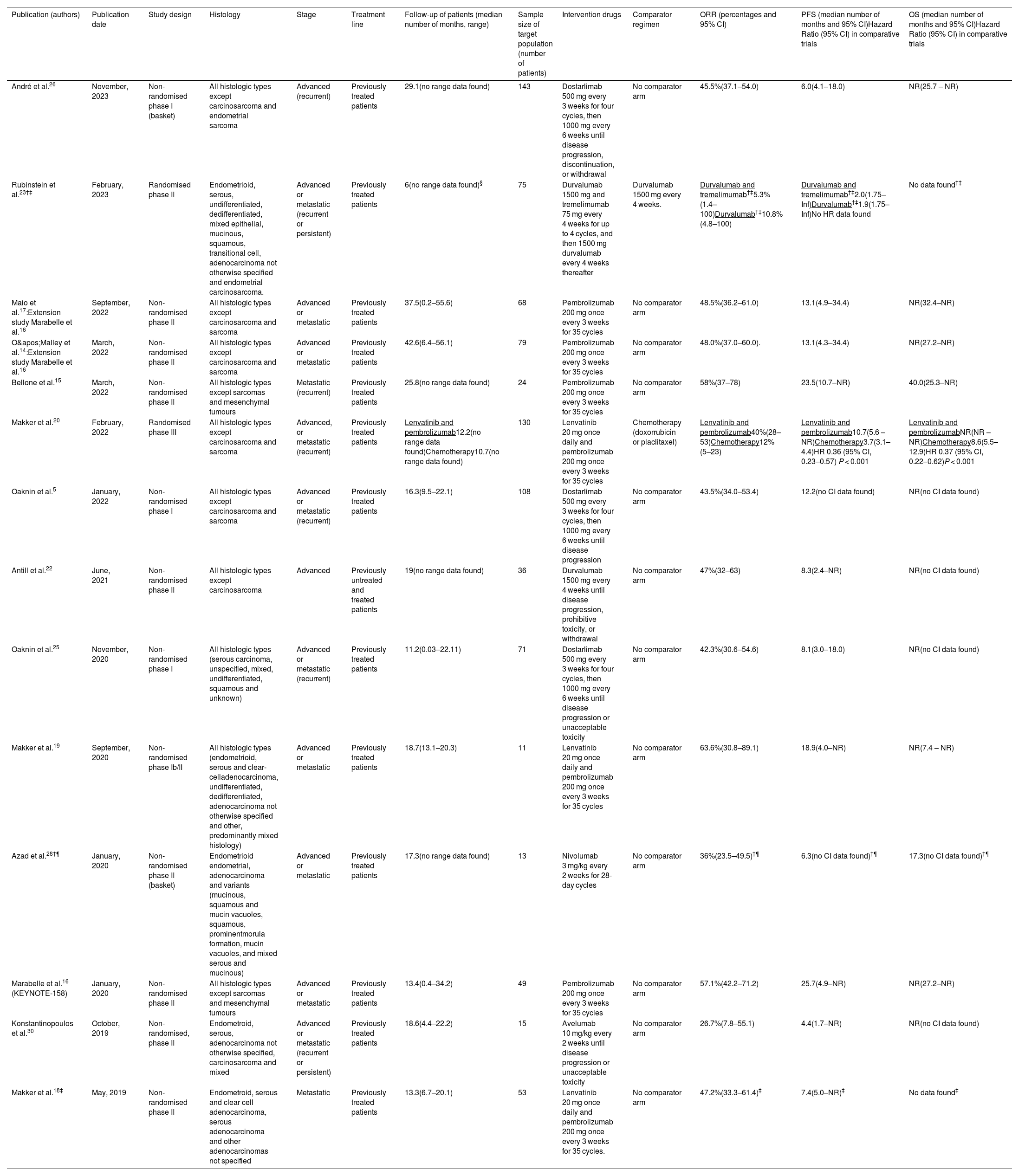

ResultsLiterature search, study selection and data extractionA total of 54 records were found in the systematic search, of which 40 publications were excluded. Reasons for exclusion of studies were as follows: 12 were developed in a different clinical context, 10 did not show efficacy outcome data for pharmacological treatments, 6 were conference communications, 4 included less than ten target patients, 3 were not a CT, 2 were duplicated, 2 did not evaluate immunotherapy and 1 showed different efficacy endpoints. Finally, 14 studies were included.5,14–20,22,23,25,26,28,30Fig. 1 shows the systematic review conducted according to PRISMA methodology. Two of the included studies14,17 were extension studies of Marabelle et al. trial.16 The designs of included studies were: 8 non-randomised phase II studies, 3 non-randomised phase I studies, 1 randomised phase II study, 1 randomised phase III study and 1 randomised phase Ib/II study. All trials included patients who had received at least one first-line platinum-based treatment. Among CTs, 14.3% included patients with advanced EC,22,26 14.3% metastatic disease,15,18 and 71.4% both.5,14,16,17,19,20,23,25,28,30 All studies reported patient follow-up data (median values between 6 and 42.6 months). Sample size of included patients ranged from 11 to 143. The regimens analysed were: pembrolizumab monotherapy, pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib combination, durvalumab, durvalumab plus tremelimumab, dostarlimab, nivolumab and avelumab. Only two trials included a comparator arm. Table 1 shows the data and results of selected studies.

Characteristics and efficacy data of studies.

| Publication (authors) | Publication date | Study design | Histology | Stage | Treatment line | Follow-up of patients (median number of months, range) | Sample size of target population (number of patients) | Intervention drugs | Comparator regimen | ORR (percentages and 95% CI) | PFS (median number of months and 95% CI)Hazard Ratio (95% CI) in comparative trials | OS (median number of months and 95% CI)Hazard Ratio (95% CI) in comparative trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| André et al.26 | November, 2023 | Non-randomised phase I (basket) | All histologic types except carcinosarcoma and endometrial sarcoma | Advanced (recurrent) | Previously treated patients | 29.1(no range data found) | 143 | Dostarlimab 500 mg every 3 weeks for four cycles, then 1000 mg every 6 weeks until disease progression, discontinuation, or withdrawal | No comparator arm | 45.5%(37.1–54.0) | 6.0(4.1–18.0) | NR(25.7 – NR) |

| Rubinstein et al.23†‡ | February, 2023 | Randomised phase II | Endometrioid, serous, undifferentiated, dedifferentiated, mixed epithelial, mucinous, squamous, transitional cell, adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified and endometrial carcinosarcoma. | Advanced or metastatic (recurrent or persistent) | Previously treated patients | 6(no range data found)§ | 75 | Durvalumab 1500 mg and tremelimumab 75 mg every 4 weeks for up to 4 cycles, and then 1500 mg durvalumab every 4 weeks thereafter | Durvalumab 1500 mg every 4 weeks. | Durvalumab and tremelimumab†‡5.3%(1.4–100)Durvalumab†‡10.8%(4.8–100) | Durvalumab and tremelimumab†‡2.0(1.75–Inf)Durvalumab†‡1.9(1.75–Inf)No HR data found | No data found†‡ |

| Maio et al.17:Extension study Marabelle et al.16 | September, 2022 | Non-randomised phase II | All histologic types except carcinosarcoma and sarcoma | Advanced or metastatic | Previously treated patients | 37.5(0.2–55.6) | 68 | Pembrolizumab 200 mg once every 3 weeks for 35 cycles | No comparator arm | 48.5%(36.2–61.0) | 13.1(4.9–34.4) | NR(32.4–NR) |

| O'Malley et al.14:Extension study Marabelle et al.16 | March, 2022 | Non-randomised phase II | All histologic types except carcinosarcoma and sarcoma | Advanced or metastatic | Previously treated patients | 42.6(6.4–56.1) | 79 | Pembrolizumab 200 mg once every 3 weeks for 35 cycles | No comparator arm | 48.0%(37.0–60.0). | 13.1(4.3–34.4) | NR(27.2–NR) |

| Bellone et al.15 | March, 2022 | Non-randomised phase II | All histologic types except sarcomas and mesenchymal tumours | Metastatic (recurrent) | Previously treated patients | 25.8(no range data found) | 24 | Pembrolizumab 200 mg once every 3 weeks for 35 cycles | No comparator arm | 58%(37–78) | 23.5(10.7–NR) | 40.0(25.3–NR) |

| Makker et al.20 | February, 2022 | Randomised phase III | All histologic types except carcinosarcoma and sarcoma | Advanced, or metastatic (recurrent) | Previously treated patients | Lenvatinib and pembrolizumab12.2(no range data found)Chemotherapy10.7(no range data found) | 130 | Lenvatinib 20 mg once daily and pembrolizumab 200 mg once every 3 weeks for 35 cycles | Chemotherapy (doxorrubicin or placlitaxel) | Lenvatinib and pembrolizumab40%(28–53)Chemotherapy12%(5–23) | Lenvatinib and pembrolizumab10.7(5.6 – NR)Chemotherapy3.7(3.1–4.4)HR 0.36 (95% CI, 0.23–0.57) P < 0.001 | Lenvatinib and pembrolizumabNR(NR – NR)Chemotherapy8.6(5.5–12.9)HR 0.37 (95% CI, 0.22–0.62)P < 0.001 |

| Oaknin et al.5 | January, 2022 | Non-randomised phase I | All histologic types except carcinosarcoma and sarcoma | Advanced or metastatic (recurrent) | Previously treated patients | 16.3(9.5–22.1) | 108 | Dostarlimab 500 mg every 3 weeks for four cycles, then 1000 mg every 6 weeks until disease progression | No comparator arm | 43.5%(34.0–53.4) | 12.2(no CI data found) | NR(no CI data found) |

| Antill et al.22 | June, 2021 | Non-randomised phase II | All histologic types except carcinosarcoma | Advanced | Previously untreated and treated patients | 19(no range data found) | 36 | Durvalumab 1500 mg every 4 weeks until disease progression, prohibitive toxicity, or withdrawal | No comparator arm | 47%(32–63) | 8.3(2.4–NR) | NR(no CI data found) |

| Oaknin et al.25 | November, 2020 | Non-randomised phase I | All histologic types (serous carcinoma, unspecified, mixed, undifferentiated, squamous and unknown) | Advanced or metastatic (recurrent) | Previously treated patients | 11.2(0.03–22.11) | 71 | Dostarlimab 500 mg every 3 weeks for four cycles, then 1000 mg every 6 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity | No comparator arm | 42.3%(30.6–54.6) | 8.1(3.0–18.0) | NR(no CI data found) |

| Makker et al.19 | September, 2020 | Non-randomised phase Ib/II | All histologic types (endometrioid, serous and clear-celladenocarcinoma, undifferentiated, dedifferentiated, adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified and other, predominantly mixed histology) | Advanced or metastatic | Previously treated patients | 18.7(13.1–20.3) | 11 | Lenvatinib 20 mg once daily and pembrolizumab 200 mg once every 3 weeks for 35 cycles | No comparator arm | 63.6%(30.8–89.1) | 18.9(4.0–NR) | NR(7.4 – NR) |

| Azad et al.28†¶ | January, 2020 | Non-randomised phase II (basket) | Endometrioid endometrial, adenocarcinoma and variants (mucinous, squamous and mucin vacuoles, squamous, prominentmorula formation, mucin vacuoles, and mixed serous and mucinous) | Advanced or metastatic | Previously treated patients | 17.3(no range data found) | 13 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks for 28-day cycles | No comparator arm | 36%(23.5–49.5)†¶ | 6.3(no CI data found)†¶ | 17.3(no CI data found)†¶ |

| Marabelle et al.16 (KEYNOTE-158) | January, 2020 | Non-randomised phase II | All histologic types except sarcomas and mesenchymal tumours | Advanced or metastatic | Previously treated patients | 13.4(0.4–34.2) | 49 | Pembrolizumab 200 mg once every 3 weeks for 35 cycles | No comparator arm | 57.1%(42.2–71.2) | 25.7(4.9–NR) | NR(27.2–NR) |

| Konstantinopoulos et al.30 | October, 2019 | Non-randomised, phase II | Endometroid, serous, adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified, carcinosarcoma and mixed | Advanced or metastatic (recurrent or persistent) | Previously treated patients | 18.6(4.4–22.2) | 15 | Avelumab 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity | No comparator arm | 26.7%(7.8–55.1) | 4.4(1.7–NR) | NR(no CI data found) |

| Makker et al.18‡ | May, 2019 | Non-randomised phase II | Endometroid, serous and clear cell adenocarcinoma, serous adenocarcinoma and other adenocarcinomas not specified | Metastatic | Previously treated patients | 13.3(6.7–20.1) | 53 | Lenvatinib 20 mg once daily and pembrolizumab 200 mg once every 3 weeks for 35 cycles. | No comparator arm | 47.2%(33.3–61.4)‡ | 7.4(5.0–NR)‡ | No data found‡ |

ORR: objective response rate; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OS: overall survival; PFS: progression-free survival; dMMR: mismatch repair deficiency; MMRp: mismatch repair proficiency; NR: not reached; HR: hazard ratio.

The largest numerical effect was achieved for pembrolizumab after a median follow-up of 25.8 months (OS = 40.0 months [95% CI, 25.3-Not Reached]); (PFS = 23.5 months [95% CI, 10.7-NR]); (ORR = 58% [95% CI, 37–78]).15 Pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib was positioned as another interesting alternative after 12.2 months of follow-up (OS = NR [95% CI, NR-NR]); (PFS = 10.7 months, [95% CI 5.6-NR]); (ORR = 40% [95% CI, 28–53]).20 No OS data were found in 2 trials (14.3%).18,23

PembrolizumabPembrolizumab is an IgG4 anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, blocking the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2.14.15 Multicohort KEYNOTE-158 study showed results on the use of pembrolizumab in patients diagnosed with cancer with MSI-H/dMMR, excluding colorectal cancer.16 This was a phase II, nonrandomized, multicenter, single-arm CT. Subsequently, two extensions of this study were published including results from D and K cohorts with patients diagnosed of EC with MSI-H/dMMR.14,17O'Malley et al.14 included 90 patients from D (n = 11) and K (n = 79) cohorts. With a median follow-up of 42.6 months (95% CI, 6.4–56.1), ORR was achieved by 48.0% (95% CI, 37.0–60.0) of patients according to an independent radiological committee. The median PFS observed was 13.1 months (95% CI, 4.3–34.4), while the median OS was not reached. Bellone et al.15 developed an investigation with similar characteristics to KEYNOTE-158 trial. Median follow-up was 25.8 months. An ORR of 58% (95% CI, 37–78) was achieved according to investigator analysis. Median PFS was 23.5 months (95% CI, 10.7–NR), and median OS was 40.0 months (95% CI, 25.3–NR).

Other trials combined pembrolizumab with lenvatinib, such as Makker et al.18 and Makker et al.19 Both studies had similar designs: single-arm phase II trial. Patients with MSI-H/dMMR and MSS/MMRp were enrolled. MSS/MMRp was detected in 94 patients by Makker et al.,19 while 11 patients presented MSI-H/dMMR. ORR based on investigator assessment in MSI-H/dMMR group was 63.6% (95% CI, 30.8–89.1). Median PFS was 18.9 months (95% CI, 4.0-NR), and median OS was not achieved in this MSI-H/dMMR group. Makker et al.20 was a phase III, randomised, open-label, comparative CT. Pembrolizumab-lenvatinib regimen was evaluated versus chemotherapy. ORR achieved in MSI-H/dMMR population was 40% (95% CI, 28–53) in pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib group and 12% (95% CI, 5–23) in the control group. Median PFS in group receiving pembrolizumab in combination with lenvatinib was 10.7 months (95% CI, 5.6–NR) and 3.7 months (95% CI, 3.1–4.4) in control group. Median OS was not reached in intervention group and 8.6 months (95% CI, 5.5–12.9) in the group receiving chemotherapy.

Concerning safety analysis, KEYNOTE-158 study showed that the most frequent AEs of pembrolizumab monotherapy were fatigue (14.6%), pruritus (12.9%) and diarrhoea (12.0%).16 With respect to grade 3 or higher AEs, pembrolizumab was associated with increased transaminases (1.7%) and pneumonitis (1.3%). A total of 9.4% of patients in KEYNOTE-158 study discontinued treatment due to AEs. No patients died from AEs associated with treatment. In the study by Bellone15, pembrolizumab frequently caused diarrhoea (56.0%), fatigue (48.0%) and skin disorders (44.0%). In this trial, the most frequent grade 3 or higher AEs were hyperglycaemia (16.0%) and diarrhoea (12.0%). No information on discontinuations, interruptions, delays or deaths was reported. In Makker et al.,20 the most common AEs of pembrolizumab-lenvatinib combination were hypertension (64.0%), hypothyroidism (57.4%) and diarrhoea (54.2%). Likewise, pembrolizumab-lenvatinib regimen showed hypertension (37.9%), weight loss (10.3%) and decreased appetite (7.9%) as predominant grade 3 or higher AEs. Furthermore, 69.2% of the population discontinued combination therapy. Two deaths occurred in the group of patients receiving pembrolizumab-lenvatinib.

DurvalumabThis IgG1 κ-type monoclonal antibody selectively blocks the interaction of PD-L1 with PD-1 and CD80.21 Two studies with durvalumab were included in this review, one of which used durvalumab-tremelimumab combination. The study by Antill22 evaluated durvalumab in monotherapy for patients with dMMR (n = 36) and MMRp (n = 35). However, 21 dMMR patients had not received any previous line of treatment. This scientific publication was a phase II, non-randomised, single-arm trial. Follow-up of dMMR population was 19 months. Investigator-assessed ORR in dMMR group reached 47% (95% CI, 32–63). Median PFS was 8.3 months (95% CI 2.4–NR), and median OS was not reached. Durvalumab plus tremelimumab regimen was evaluated in a phase II, randomised, open-label, active comparator study.23 Thirty-eight patients were assigned to the durvalumab monotherapy arm and 39 patients to the durvalumab-tremelimumab combination. dMMR was determined in 13.2% of patients treated with durvalumab monotherapy and 10.3% in population with a combination of immunotherapeutic agents. ORR at 6 months was 10.8% (90% CI, 4.8–100) in durvalumab arm and 5.3% (90% CI, 1.4–100) in durvalumab-tremelimumab scheme arm. Median PFS was similar in both arms: 1.9 months (90% CI, 1.75–Inf) for durvalumab and 2.0 months (90% CI, 1.75–Inf) for durvalumab plus tremelimumab. No OS data were found.

Immune-mediated AEs were collected in Antill et al.22 highlighting thyroid disorders: hypothyroidism (14.0%) and hyperthyroidism (9.0%). Three patients discontinued treatment due to AEs. No other safety data were reported in this trial. In Rubinstein et al.,23 the most frequent AEs were hyperglycemia (95% in monotherapy arm and 92% in durvalumab-tremelimumab group) and anaemia (82.0% and 87.0%, respectively). The most common grade 3 or higher AEs were: anaemia (29.0% for durvalumab and 28.0% for durvalumab-tremelimumab regimen) and decreased lymphocyte count (26.0% and 38.0%, respectively). Data on treatment reductions, discontinuations, or deaths due to AEs were not reported.

DostarlimabThe mechanism of action of this IgG4 monoclonal antibody is based on binding to PD-1 receptors and blocking their association with PD-L1 and PD-L2.24 A single-arm phase I trial was found. In the first published results, Oaknin et al.25 included patients with MSI-H/dMMR profile. In an update by Oaknin et al.,5 two cohorts were established: cohort A1 (MSI-H/dMMR, n = 108) and cohort A2 (MMRp/MSS, n = 161). ORR was similar in both publications: 42.3% (95% CI, 30.6–54.6) from Oaknin et al.25vs. 43.5% (95% CI, 34.0–53.4) in the A1 cohort.5 In both papers, ORR was assessed by a blinded independent central committee. On the other hand, PFS was 8.1 months (95% CI, 3.0–18.0) in Oaknin et al.25versus 12.2 months (no CI data) in the most updated publication. Median OS was not reached in either study. Subsequently, a phase I single-arm trial by André et al.26 enrolled patients diagnosed with different solid tumours. This trial included a post-hoc analysis presenting the results disaggregated by tumour type. For 143 patients diagnosed of EC with dMMR or mutated POLE, an independent committee determined an ORR of 45.5% (95% CI, 37.1–54.0). Median PFS was 6.0 (95% CI, 4.1–18.0) months, and median OS was not reached (95% CI, 25.7–NR).

Up to 93.9% and 95.3% of patients in Oaknin et al.25 and Oaknin et al.,5 respectively, experienced an AE. In patients diagnosed of EC and dMMR, the most frequent AEs were diarrhoea (15.4% and 16.3% in 2020 and 2022 studies, respectively) and asthenia (15.4% and 14.0%). Considering AEs of grade 3 or higher, anaemia was the most common in both studies (2.9% and 3.9%). A total of 23.1% of patients in Oaknin et al.25 presented to discontinue treatment due to AEs. Nevertheless, in Oaknin et al.,5 such discontinuations occurred in 3.9%. No deaths were recorded in dostarlimab groups in both studies.

Safety analysis in André et al.26 included the overall population without differentiation by solid tumour type. The most frequent AEs were diarrhoea (15.4%) and asthenia (14.3%). Anaemia (2.5%) and increased transaminases (1.9%) were found as AEs of grade 3 or higher. Treatment discontinuations were led by AEs in 6.9% of subjects. There were two deaths attributed to treatment, but none in the population with EC and dMMR.

NivolumabNivolumab is an IgG4 monoclonal antibody that prevents the interaction between the PD-1 receptor and PD-L1.27 The study found was a phase II basket single-arm CT with several types of tumours.28 Median patient follow-up was 17.3 months. The efficacy outcomes achieved by the global population were: ORR = 36% (90% CI, 23.5–49.5), median PFS = 6.3 months and median OS = 17.3 months (both outcomes without reported CIs).

Regarding safety, the most frequent AEs were fatigue (40%), anaemia (33%) and skin rash (17%). Likewise, anaemia (18.4%), dehydration (5.3%), fatigue (5.3%), maculo-papular rash (5.3%), sepsis (5.3%) and skin infections (5.3%) were the most common grade 3 or higher AEs. No data were available on treatment reductions, discontinuations or deaths due to AEs.

AvelumabAvelumab is an IgG1 class monoclonal antibody that interacts with PD-L1 by preventing binding to PD-1 and B7.1.29 Konstantinopoulos et al.30 consisted of a phase II single-arm CT with two cohorts. The selected population was distributed according to the presence of dMMR/POLE mutated (n = 15) or MMRp/POLE without mutations (n = 16). The co-primary endpoints were ORR and PFS at 6 months. OS was also measured as a secondary endpoint. With a median follow-up of 18.6 months, ORR in dMMR/POLE cohort was 26.7% (95% CI, 7.8–55.1). PFS at 6 months was 40.0% (95% CI, 16.3–66.7), while the median was 4.4 (95% CI, 1.7–NR). Median OS was not reached.

Concerning safety, 71.0% of patients presented at least one AE. Fatigue (35.5%) followed by nausea (16%) were the most frequent AEs. Grade 3 or higher AEs were registered in 19.4% of cases, most frequently being: anaemia (6.5%), diarrhoea (6.5%), bradycardia (3.2%), hypothyroidism (3.2%), myositis (3.2%) and rash acneiform (3.2%). No data were available on treatment reductions, discontinuations or deaths due to AEs.

Risk of biasDurvalumab presented global data from a population involving previously untreated and pre-treated patients.22 Sample sizes of CTs ranged from 11 (pembrolizumab-lenvatinib regimen, Makker et al.19 to 143 (dostarlimab)26 patients. CTs of schemes with the smallest sample sizes were: pembrolizumab-lenvatinib combination (n = 11),19 nivolumab (n = 13),28 avelumab (n = 15),30 pembrolizumab monotherapy (n = 24)15 and durvalumab (n = 36).22 Median follow-up of estudies ranged from 6 (durvalumab-tremelimumab combination)23 to 42.6 (pembrolizumab)14 months. Follow-up period was reported by all CTs.

All of the included studies had an overall assessment of a low risk of bias when the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool was applied. Fig. 2 shows the analysis with the risk of bias assessment tool.

DiscussionThe efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy and the combination of pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib in patients with advanced and/or metastatic EC with MSI-H/dMMR seems to be promising. However, rigorous therapeutic positioning is not possible with the CTs evaluated. Pembrolizumab monotherapy –with an ORR of 58%, median PFS of 23.5 months and OS of 40 months15– would be placed as the alternative with the greatest numerical effect, pending more mature data from better-designed CTs. Pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib combination was evaluated in a higher-quality study (randomised phase III CT) with a follow-up of 12.2 months.20 This regimen showed an ORR of 40% and a median PFS of 10.7 months, without reaching a median OS. In addition, durvalumab and dostarlimab have also been evaluated.22,26 After a 19-month follow-up, durvalumab demonstrated an ORR of 47% and a median PFS of 8.3 months, without achieving a median OS.22 These data were significantly biased, as they were obtained from a heterogeneous population including previously untreated patients. With a median follow-up of 29.1 months, dostarlimab achieved an ORR of 45.5% and a median PFS of 6 months, with a median OS not reached.26 Nivolumab was evaluated in a basket design trial.28 This antibody showed an ORR of 36%, median PFS of 6.3 months and OS of 17.3 months. The design of this CT mixed results from very heterogeneous pathologies, so few conclusions could be extracted from its data. On the other hand, avelumab presented poor results in dMMR patients with an ORR of 26.7% and a median PFS of 4.4 months.30 With respect to safety, the most common AEs were fatigue (up to 40% of patients with nivolumab),28 anaemia (33% of patients with nivolumab)28 and gastrointestinal AEs (up to 16% of patients experienced nausea with avelumab,30 and 16.3% diarrhoea with dostarlimab5,25). Anaemia was the most frequent grade 3 or higher AE, particularly with durvalumab (29% of patients).22 About immunotherapy combinations, pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib appeared to show numerically superior efficacy data compared to durvalumab plus tremelimumab.18–20,23 The absence of common comparators prevents the confirmation of these numerical differences for proper a reliable therapeutic positioning. Likewise, the combination of pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib has not yet demonstrated a clear benefit over pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with MSI-H/dMMR.16,20 In fact, ORR was lower with the combination regimen (40% vs 58%). PFS and OS values would be in favour of pembrolizumab monotherapy. Nevertheless, these comments are simple numerical comparisons. The current design and median follow-up of the CTs do not allow for rigorous efficacy comparisons. In addition, the combination of pembrolizumab with lenvatinib shows a worse safety profile given the higher number of treatment discontinuations compared to monotherapy.16,20

Some of the studies designed two cohorts based on the different MS error repair capacity. A tumour characterised as MSI-H could be considered as dMMR. Similarly, a neoplasm determined as MSI-L or MSS could be assessed as MMRp. However, the criterion for classifying a tumour as MMS or MSI-L is not clearly defined.6,7 In CTs that performed analyses according to MS repair, MSI-H/dMMR populations suggested better results with immunotherapy than those with MSS/MMRp. MSI-H/dMMR tumours are associated with increased tumour neoantigen load, lymphocyte infiltration and increased PD-1 and PD-L1 expression.9 This leads to an overexpression of the immune response. Despite this, patients with MSS/MMRp tumours may also benefit from the use of some immunotherapy regimens over chemotherapy, as can be seen in the subgroup analysis of Makker et al.20

CTs included in this review generally recruited a small sample size of patients diagnosed with EC and MSI. The lower likelihood of finding patients with MSI-H/dMMR profile makes it difficult to reliably detect differences in drug response compared to the MSS/MMRp population.31 This is essential to develop a correct subgroup analysis for each of the therapeutic alternatives. Approvals by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) are currently based on results from CT in patients with MSI-H/dMMR. On 25 February 2021, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) issued a positive opinion for dostarlimab as monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with MSI-H/dMMR who have progressed during or after prior treatment with a platinum-based regimen.32 On 24 March 2022, pembrolizumab received a positive CHMP opinion for the same indication.33

Our review included EC previously treated with at least one prior line of primarily platinum-based regimens. Recent publications such as Mirza et al.34 and Eskander et al.35 used dostarlimab and pembrolizumab, respectively, combined with chemotherapy in naïve patients. Mirza et al.34 included 118 patients with dMMR: 53 cases received dostarlimab plus chemotherapy and 65 patients were assigned to the chemotherapy group. Results in dostarlimab plus chemotherapy arm were superior in terms of OS and PFS compared to control arm. Eskander et al.35 conducted a study similar to Mirza et al.34 They enrolled 225 previously untreated patients with MSI-H/dMMR: 112 cases received pembrolizumab-chemotherapy scheme and 113 patients received chemotherapy. After 12 months of follow-up, median PFS was not reached in pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy arm compared to 7.6 months in the control group.

Limitations of the included CTs are small sample sizes and lack of comparators in most of the studies. Only Rubinstein et al.23 and Makker et al.20 developed a comparative design and none of the studies reported a common comparator. Single-arm studies make it difficult to extrapolate results to clinical practice. The lack of randomisation does not allow adjustment for the effect of unknown benefit-related factors. Moreover, adjustment for a few known factors that influence outcomes has limitations. Lack of stratification or heterogeneous populations in non-randomised trials can lead to significant bias in indirect comparisons. Therefore, the establishment of reliable indirect comparisons requires common comparator drugs for proper therapeutic positioning. Adjusted indirect comparisons or network meta-analyses require common treatments such as comparator linkages. In addition, no mature results on an endpoint such as OS have been obtained in some of the trials discussed. Even no OS data were detailed in other CTs. On the other hand, ORR is a surrogate endpoint that could lead to bias and it was frequently used as a primary endpoint. Therefore, some trials –such as Oaknin et al.5 and Marabelle et al.16– incorporated an independent committee to assess ORR and reduce the subjective influence of investigators.

Subgroup analyses should be carefully designed. A minimum sample size of 50 patients per arm is required to assess the results for each factor evaluated.36 In our review, we found only three trials with more than 100 patients.5,20,26 In order to interpret outcomes by subgroups, it would be advisable to design larger comparative studies exclusively for the population of EC with MSI previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. In this way, subgroup analyses could be developed within these CTs that could adequately assess the impact of biomarkers such as PD-1 or PD-L1. Until now, the contribution of results according to PD-L1 expression is almost non-existent. There are some cases where low-quality data were reported from heterogeneous populations or mixing of multiple biomarkers. André et al.26 presented ORR by biomarker status in a combined analysis of patients with dMMR solid tumours (not exclusively of our target population with EC). The results were described according to tumour mutational burden (TMB) and PD-L1: TMB-high/PD-L1–high tumours had ORR (60.4%), TMB-low/PD-L1–low (25.0%), TMB-high/PD-L1–low (32.3%) and TMB-low/PD-L1–high (42.9%). These data are difficult to compare with the rest of the data from other trials.

Characterisation of the MS profile in EC could be important to identify which patients may benefit most from treatments. However, comparative phase III trials are essential to correctly position the results of all therapeutic alternatives. Few CTs have shown mature data in OS. Studies with larger sample size, longer follow-up and better designs are needed, as well as appropriately designed subgroup analyses based on differences in MS repair mechanisms.

Conference PresentationsIt has not been presented at any conference previously.

Conflicts of interestGil-Sierra Manuel David: advisory board membership (consultancy fees) for Janssen Pharmaceutica and reimbursement for symposium attendance for Pfizer for other cancer drugs. The rest of the authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication. It is declared that the authors have read and approved the manuscript, and that the authorship requirements are met:

- –

Moreno-Ramos Cristina: Conception and design of the study, data search and processing, clinical interpretation of the data, literature review on the study and background, manuscript preparation, as well as its review and submission management, final approval of the version to be published.

- –

Gil-Sierra Manuel David: Conception and design of the study, data search and processing, clinical interpretation of the data, literature review on the study and background, manuscript preparation, as well as its review and submission management, final approval of the version to be published.

- –

Briceño-Casado Maria del Pilar: Conception and design of the study, data search and processing, clinical interpretation of the data, literature review on the study and background, manuscript preparation, as well as its review and submission management, final approval of the version to be published.

In addition to the activities described above, all authors confirm their participation in the following contributions:

- –

Conception and design of the work, data collection, or data analysis and interpretation.

- –

Writing the article or critically reviewing it with significant intellectual contributions.

- –

Approval of the final version for publication.

- –

Taking responsibility and being accountable that all aspects of the manuscript have been reviewed and discussed among the authors to ensure they are presented with maximum accuracy and integrity.

This clause is accepted by all signing authors of the manuscript.

The authors explicitly declare that the work has not been previously published nor is it under review elsewhere.

The authors state that they have followed the instructions for authors and ethical responsibilities, including that all signing authors meet authorship criteria and have declared their respective conflicts of interest.

All necessary ethical responsibilities regarding authorship and redundant publication have been fulfilled (protection of research subjects, including humans and animals, and informed consent were not required due to the study design).

We, the authors, accept the responsibilities defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (available at http://www.icmje.org/).

The authors transfer, in the event of publication, exclusive rights of reproduction, distribution, translation, and public communication (by any means or support—sound, audiovisual, or electronic) of our work to Farmacia Hospitalaria and, by extension, to SEFH. A rights transfer letter will be signed at the time of manuscript submission through the online manuscript management system.

CRediT authorship contribution statementCristina Moreno-Ramos: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Manuel David Gil-Sierra: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. María del Pilar Briceño-Casado: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

AcknowledgmentsThis study was funded as “Research Project” for one of the “Grants 2023” from the Andalusian Hospital Pharmacy Foundation of the Andalusian Society of Hospital Pharmacists.