Collecting updated information on the organization of Hospital Pharmacy specialty rotations in different areas across Spanish hospitals, in order to create a map of residency rotations for hospital pharmacy residents, serving as a guideline and reference for hospital pharmacy tutors.

MethodA cross-sectional, multicenter descriptive study on the planning of residency rotations for hospital pharmacy interns in hospitals accredited for specialized healthcare training in Spain. An online survey was designed and distributed via mailing list by the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy between May and June 2024. The survey, validated and tested in a pilot sample, gathered general information about the hospital, rotations by areas of activity (year of residency, duration, complete/partial modality, shared rotations), external and elective rotations, additional training, supervision and assessment of the residents. Data were analyzed descriptively, including measures of central tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables and frequencies for categorical variables.

ResultsThe response rate was 86.8%. A basic initial rotation is present in 88.9% of hospitals, with a median duration of 6.5 weeks. Stock management, compounding, and validation and dispensing to inpatients are primarily carried out during the first year, while nutrition and oncology are concentrated in the 2nd year. Outpatient pharmaceutical care, clinical trials, medication evaluation and selection, drug information, and pharmacokinetics are conducted in the third year, whereas management/administration, primary care, and pharmaceutical care in clinical units are undertaken in the 4th year. The most common clinical rotations include Infectious Diseases (70.7%) and Hematology (67.7%). The duration of rotations varies between 1 and 9 months, with many organized as shared rotations, particularly in drug information and medication evaluation. Rotations not included in the official programme are included in 93.3% of hospitals, 91.9% of residents participate in clinical committees, and 22.2% have the opportunity to pursue a PhD.

ConclusionsThis study shows considerable variability in the organization of training programs across hospital pharmacy teaching units in Spain.

recopilar información actualizada sobre la organización de las rotaciones de la especialidad de farmacia hospitalaria en las distintas áreas en los hospitales españoles, con el fin de elaborar un mapa de las rotaciones de los farmacéuticos internos residentes que sirva de guía y referencia a los tutores de farmacia hospitalaria.

Métodoestudio descriptivo transversal multicéntrico sobre la planificación de las rotaciones de los residentes de farmacia hospitalaria en hospitales acreditados para la formación sanitaria especializada en España. Se diseñó una encuesta online que se distribuyó mediante lista de correo por la Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria entre mayo y junio de 2024. La encuesta, validada y probada en una muestra piloto, recopiló información general del hospital, rotaciones por áreas de actividad (año de residencia, duración, modalidad completa/parcial, rotaciones compartidas), rotaciones externas y libres, formación adicional y supervisión y evaluación de los residentes. Los datos se analizaron descriptivamente, incluyendo medidas de tendencia central y dispersión para las variables cuantitativas y frecuencias para las categóricas.

Resultadosla tasa de respuesta fue del 86,8%. El 88,9% de los hospitales tienen una rotación básica inicial, con una mediana de duración de 6,5 semanas. Las rotaciones de gestión de stocks, farmacotecnia y validación y dispensación al paciente ingresado se realizan principalmente en el primer año de residencia, mientras que nutrición artificial y oncología se concentran en el segundo. Atención farmacéutica al paciente externo, ensayos clínicos, evaluación de medicamentos, información de medicamentos y farmacocinética se llevan a cabo en el tercer año, mientras que dirección/gestión, atención primaria y atención farmacéutica en unidades clínicas se realizan en el cuarto año. Las rotaciones clínicas más comunes incluyen enfermedades infecciosas (70,7%) y hematología (67,7%). La duración media de las rotaciones varía entre 1 y 9 meses, muchas organizadas de manera compartida, especialmente en información y evaluación de medicamentos. El 93,3% de los hospitales incluye rotaciones no contempladas en el programa nacional, el 91,9% de los residentes participa en comisiones clínicas y el 22,2% tiene posibilidad de realizar un doctorado.

Conclusioneseste estudio muestra una considerable variabilidad en la organización de los itinerarios formativos de cada unidad docente de farmacia hospitalaria en España.

The training of hospital pharmacy residents (farmacéuticos internos residentes, FIR in Spanish) began in 1977 with the first call for specialised training positions for pharmacists in Spain.1,2 Since then, this process has been essential for the evolution of the specialty. However, since the last update of the programme in 19993, the profession has undergone significant changes in the scientific, technological, and healthcare fields.4,5

The 4-year programme defines competencies across 12 training areas, including drug information, compounding, oncology pharmacy, clinical pharmacokinetics, outpatient care, and overall management of the pharmacy service. There are also permanent and transversal activities such as research, teaching, and quality improvement. Although the duration of rotations is established at between 3 and 6 months, the programme does not specify their temporal distribution, except for a basic rotation of 6 months in the first year and clinical rotations in the fourth year, which must include inpatient pharmaceutical care, surgical areas, and outpatient areas, without detailing specific departments.3 Under these premises, each hospital accredited for teaching designs their own standard training programme, and the tutor adapts it to an individualised training plan for each resident. This lack of clear guidelines on time schedules provides tutors and centres with the flexibility to adjust the programme, but it can also generate variability in the residents' training.

In addition, the lack of updates in the official programme, excludes key areas that have gained importance in today's hospital pharmacy services. Areas such as transversal skills, pharmaceutical care in advanced therapies (CAR-T, gene therapies), pharmacogenomics, and the management of chronic conditions are not included in the current official programme of the specialty.3,6 Moreover, the need for on-call duty is not described. This lack of updating in the training programmes may also lead to variability in resident education across accredited hospitals.

Given such a flexible structure, the ongoing professional developments, and potentially outdated training programmes, it has become necessary to evaluate the current design of hospital pharmacy residency rotations in Spanish hospitals. This study aimed to collect current data on the organisation of rotations within hospital pharmacy departments across Spanish hospitals. The resulting mapping of resident pharmacist training structures will serve as a practical reference framework for hospital pharmacy tutors.

MethodsA descriptive, cross-sectional, multicentre study was conducted by the Tutors' Working Group of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH) using a voluntary online survey to evaluate the organisation of hospital pharmacy residency rotations.

Study population: hospital pharmacy services (HPS) accredited for specialised healthcare training in Spain. This is a finite and well-defined sample with a total population of 114 teaching units.

Survey designThe survey was designed through consensus by the Tutors' Working Group and implemented in an online self-completion format using Google Forms. Subsequently, a group of specialist training experts reviewed the survey content for clarity and completeness. Following validation, we conducted a pilot test with 5 tutors who completed the survey and provided feedback. Their suggestions guided adjustments to the format and wording of the questionnaire to improve clarity and usability.

The survey included an introductory text outlining the study objectives, emphasising that participation was voluntary and specifying that only 1 survey per hospital should be completed. The survey included 83 questions (Annex 1) that covered the following aspects:

- •

General information about the hospital: autonomous community's location, number of beds available, number of accredited FIR positions per year, number of residents and tutors, academic profile, and affiliation to SEFH Tutors' Working Groups.

- •

Rotations by areas of activity: detailed information was requested about residents' rotations in the activity areas comprising the service's training programme. For each training area, the following data were requested: the residency year, rotation duration (in months or weeks), modality (full-time or part-time), and any additional areas with which the rotation was shared.

- •

External rotations: availability, duration, and residency year when conducted, plus optional elective rotations.

- •

Additional training: participation in clinical committees, courses, master's programmes and congresses, along with research and doctoral activities.

- •

Supervision and evaluation: assessment tools used, frequency of tutor-resident interviews, and existence of written supervision protocols.

The survey employed closed-ended questions with either binary response options (yes/no; full-time/part-time) or single-selection multiple-choice options (presented as dropdown menus where only 1 predefined answer could be selected). Other multiple-choice questions allowed several options to be selected from the drop-down list. The survey also included conditional questions that were triggered based on prior responses. For instance, selecting part-time rotations activated follow-up questions about which clinical areas shared these rotational assignments. Annex 1 provides details of the questionnaire, type of questions, and response options.

Survey distributionThe tutor survey was distributed via the SEFH mailing list between May and June 2024, with instructions for each hospital to submit the survey only once.

To improve the questionnaire return rate, the Tutors' Working Group sent a reminder by email. Additionally, when no response was received from the HPSs' tutors in the first round, follow-up communications were conducted by email or by phone.

Data analysisAs the survey targeted all HPS-accredited hospitals providing specialised healthcare training in Spain, no prior sample size calculation was required, because there was no intent to extrapolate findings to a broader population.

The replies were compiled in an Excel database accessible only to the research team. A preliminary analysis was performed to identify duplicate entries and correct possible errors in variable coding. Subsequent statistical analysis proceeded in 2 phases. For continuous variables, we calculated central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion measures (range, standard deviation).

Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. For questions with a response rate below 100%, percentages were calculated relative to the actual number of responding HPSs per item.

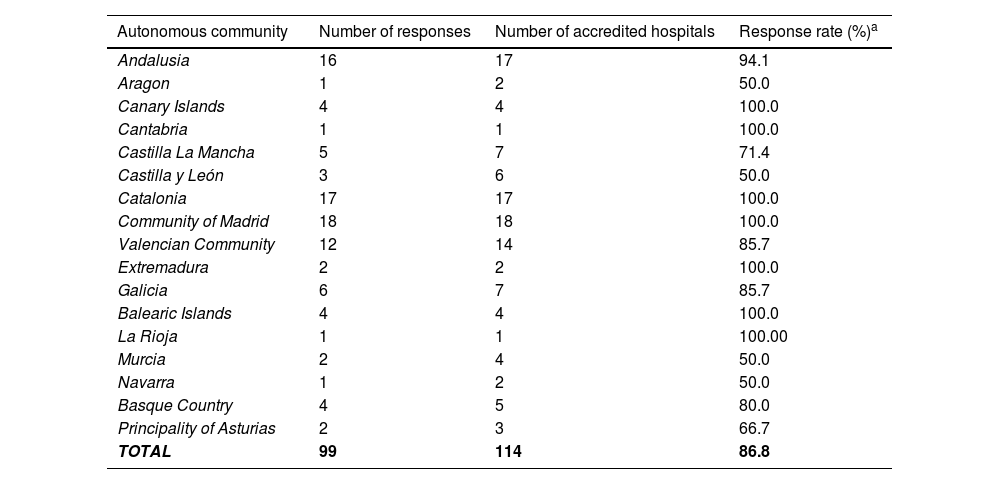

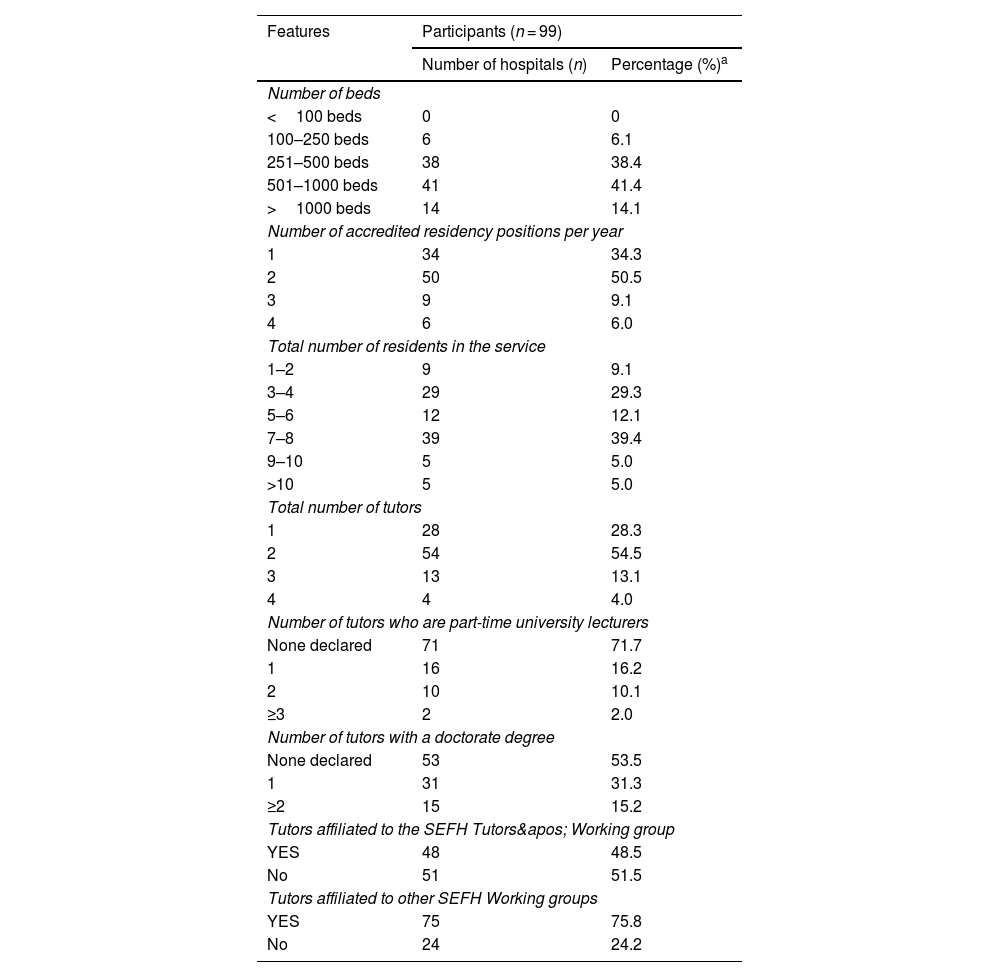

ResultsFrom the 114 hospitals with accredited teaching units, 99 responses were received, representing an 86.8% response rate. Tables 1 and 2 show the response rate by autonomous community and the characteristics of the responding HPSs. Among the accredited HPSs, 79.8% had between 251 and 1000 beds, 84.8% were accredited for 1 to 2 positions annually, and 54.5% had 2 tutors.

Distribution of the response rate by autonomous community in hospital pharmacy residencyaccredited hospitals.

| Autonomous community | Number of responses | Number of accredited hospitals | Response rate (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 16 | 17 | 94.1 |

| Aragon | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| Canary Islands | 4 | 4 | 100.0 |

| Cantabria | 1 | 1 | 100.0 |

| Castilla La Mancha | 5 | 7 | 71.4 |

| Castilla y León | 3 | 6 | 50.0 |

| Catalonia | 17 | 17 | 100.0 |

| Community of Madrid | 18 | 18 | 100.0 |

| Valencian Community | 12 | 14 | 85.7 |

| Extremadura | 2 | 2 | 100.0 |

| Galicia | 6 | 7 | 85.7 |

| Balearic Islands | 4 | 4 | 100.0 |

| La Rioja | 1 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Murcia | 2 | 4 | 50.0 |

| Navarra | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| Basque Country | 4 | 5 | 80.0 |

| Principality of Asturias | 2 | 3 | 66.7 |

| TOTAL | 99 | 114 | 86.8 |

Structural and teaching characteristics of the hospitals participating in the study.

| Features | Participants (n = 99) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of hospitals (n) | Percentage (%)a | |

| Number of beds | ||

| <100 beds | 0 | 0 |

| 100–250 beds | 6 | 6.1 |

| 251–500 beds | 38 | 38.4 |

| 501–1000 beds | 41 | 41.4 |

| >1000 beds | 14 | 14.1 |

| Number of accredited residency positions per year | ||

| 1 | 34 | 34.3 |

| 2 | 50 | 50.5 |

| 3 | 9 | 9.1 |

| 4 | 6 | 6.0 |

| Total number of residents in the service | ||

| 1–2 | 9 | 9.1 |

| 3–4 | 29 | 29.3 |

| 5–6 | 12 | 12.1 |

| 7–8 | 39 | 39.4 |

| 9–10 | 5 | 5.0 |

| >10 | 5 | 5.0 |

| Total number of tutors | ||

| 1 | 28 | 28.3 |

| 2 | 54 | 54.5 |

| 3 | 13 | 13.1 |

| 4 | 4 | 4.0 |

| Number of tutors who are part-time university lecturers | ||

| None declared | 71 | 71.7 |

| 1 | 16 | 16.2 |

| 2 | 10 | 10.1 |

| ≥3 | 2 | 2.0 |

| Number of tutors with a doctorate degree | ||

| None declared | 53 | 53.5 |

| 1 | 31 | 31.3 |

| ≥2 | 15 | 15.2 |

| Tutors affiliated to the SEFH Tutors' Working group | ||

| YES | 48 | 48.5 |

| No | 51 | 51.5 |

| Tutors affiliated to other SEFH Working groups | ||

| YES | 75 | 75.8 |

| No | 24 | 24.2 |

SEFH, Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy.

For first-year residents (R1), 88.9% (88) of HPSs included an initial basic rotation in their training programme, with a median duration of 6.5 (4–12) weeks. Among these HPSs, 61.4% (54) allocated >4 weeks to this rotation: 27.3% (24) allocated 5–8 weeks, 14.8% (13) 9–12 weeks, and 19.3% (17) periods exceeding 12 weeks.

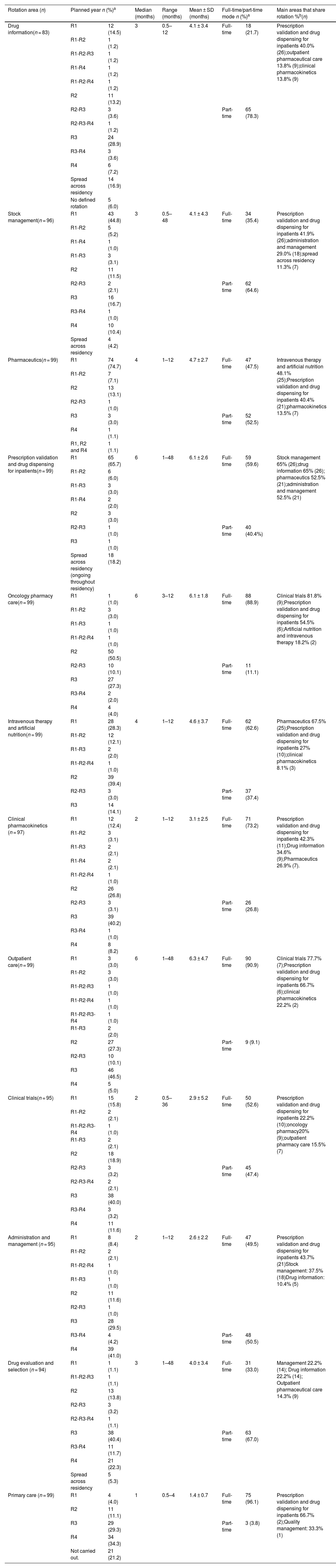

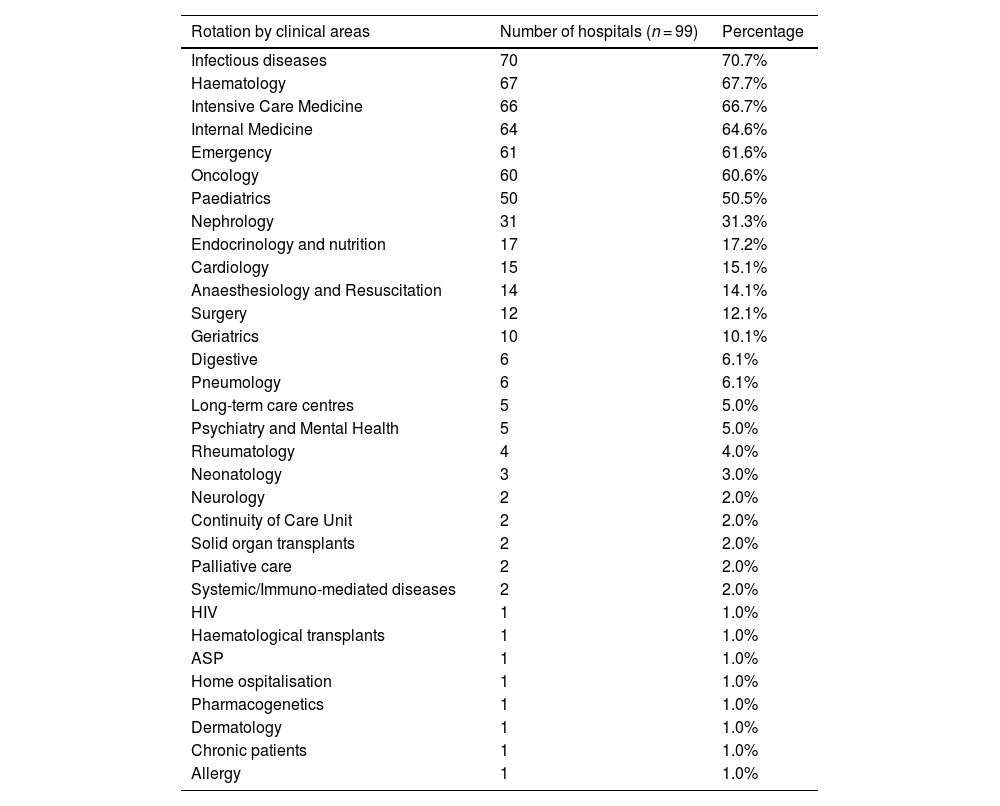

The organisation of rotations is described in Table 3, which includes data on the planned year, duration, and full- or part-time modality for each training area. The rotations by clinical units are detailed in Table 4. By residency year, first-year residents (R1) rotated mainly in basic areas: compounding, prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients, and stock management. Second-year residents (R2) most frequently undertook rotations in oncology pharmacy, artificial nutrition, and intravenous therapy. In their third year (R3), rotations mainly focussed on clinical trials, pharmacokinetics, outpatient pharmaceutical care, along with drug evaluation and information. Fourth-year (R4) residents completed their training with rotations in pharmaceutical care in clinical units, administration and management, and primary care.

Organisation of hospital pharmacy resident rotations according to the official programme in Spanish hospitals accredited for teaching.

| Rotation area (n) | Planned year n (%)a | Median (months) | Range (months) | Mean ± SD (months) | Full-time/part-time mode n (%)a | Main areas that share rotation %b(n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug information(n = 83) | R1 | 12 (14.5) | 3 | 0.5–12 | 4.1 ± 3.4 | Full-time | 18 (21.7) | Prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients 40.0% (26);outpatient pharmaceutical care 13.8% (9);clinical pharmacokinetics 13.8% (9) |

| R1-R2 | 1 (1.2) | |||||||

| R1-R2-R3 | 1 (1.2) | |||||||

| R1-R4 | 1 (1.2) | |||||||

| R1-R2-R4 | 1 (1.2) | |||||||

| R2 | 11 (13.2) | |||||||

| R2-R3 | 3 (3.6) | Part-time | 65 (78.3) | |||||

| R2-R3-R4 | 1 (1.2) | |||||||

| R3 | 24 (28.9) | |||||||

| R3-R4 | 3 (3.6) | |||||||

| R4 | 6 (7.2) | |||||||

| Spread across residency | 14 (16.9) | |||||||

| No defined rotation | 5 (6.0) | |||||||

| Stock management(n = 96) | R1 | 43 (44.8) | 3 | 0.5–48 | 4.1 ± 4.3 | Full-time | 34 (35.4) | Prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients 41.9% (26);administration and management 29.0% (18);spread across residency 11.3% (7) |

| R1-R2 | 5 (5.2) | |||||||

| R1-R4 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R1-R3 | 3 (3.1) | |||||||

| R2 | 11 (11.5) | |||||||

| R2-R3 | 2 (2.1) | Part-time | 62 (64.6) | |||||

| R3 | 16 (16.7) | |||||||

| R3-R4 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R4 | 10 (10.4) | |||||||

| Spread across residency | 4 (4.2) | |||||||

| Pharmaceutics(n = 99) | R1 | 74 (74.7) | 4 | 1–12 | 4.7 ± 2.7 | Full-time | 47 (47.5) | Intravenous therapy and artificial nutrition 48.1% (25);Prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients 40.4% (21);pharmacokinetics 13.5% (7) |

| R1-R2 | 7 (7.1) | |||||||

| R2 | 13 (13.1) | |||||||

| R2-R3 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R3 | 3 (3.0) | Part-time | 52 (52.5) | |||||

| R4 | 1 (1.1) | |||||||

| R1, R2 and R4 | 1 (1.1) | |||||||

| Prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients(n = 99) | R1 | 65 (65.7) | 6 | 1–48 | 6.1 ± 2.6 | Full-time | 59 (59.6) | Stock management 65% (26);drug information 65% (26); pharmaceutics 52.5% (21);administration and management 52.5% (21) |

| R1-R2 | 6 (6.0) | |||||||

| R1-R3 | 3 (3.0) | |||||||

| R1-R4 | 2 (2.0) | |||||||

| R2 | 3 (3.0) | |||||||

| R2-R3 | 1 (1.0) | Part-time | 40 (40.4%) | |||||

| R3 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| Spread across residency (ongoing throughout residency) | 18 (18.2) | |||||||

| Oncology pharmacy care(n = 99) | R1 | 1 (1.0) | 6 | 3–12 | 6.1 ± 1.8 | Full-time | 88 (88.9) | Clinical trials 81.8% (9);Prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients 54.5% (6);Artificial nutrition and intravenous therapy 18.2% (2) |

| R1-R2 | 3 (3.0) | |||||||

| R1-R3 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R1-R2-R4 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R2 | 50 (50.5) | |||||||

| R2-R3 | 10 (10.1) | Part-time | 11 (11.1) | |||||

| R3 | 27 (27.3) | |||||||

| R3-R4 | 2 (2.0) | |||||||

| R4 | 4 (4.0) | |||||||

| Intravenous therapy and artificial nutrition(n = 99) | R1 | 28 (28.3) | 4 | 1–12 | 4.6 ± 3.7 | Full-time | 62 (62.6) | Pharmaceutics 67.5% (25);Prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients 27% (10);clinical pharmacokinetics 8.1% (3) |

| R1-R2 | 12 (12.1) | |||||||

| R1-R3 | 2 (2.0) | |||||||

| R1-R2-R4 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R2 | 39 (39.4) | |||||||

| R2-R3 | 3 (3.0) | Part-time | 37 (37.4) | |||||

| R3 | 14 (14.1) | |||||||

| Clinical pharmacokinetics (n = 97) | R1 | 12 (12.4) | 2 | 1–12 | 3.1 ± 2.5 | Full-time | 71 (73.2) | Prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients 42.3% (11);Drug information 34.6% (9);Pharmaceutics 26.9% (7). |

| R1-R2 | 3 (3.1) | |||||||

| R1-R3 | 2 (2.1) | |||||||

| R1-R4 | 2 (2.1) | |||||||

| R1-R2-R4 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R2 | 26 (26.8) | |||||||

| R2-R3 | 3 (3.1) | Part-time | 26 (26.8) | |||||

| R3 | 39 (40.2) | |||||||

| R3-R4 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R4 | 8 (8.2) | |||||||

| Outpatient care(n = 99) | R1 | 3 (3.0) | 6 | 1–48 | 6.3 ± 4.7 | Full-time | 90 (90.9) | Clinical trials 77.7% (7);Prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients 66.7% (6);clinical pharmacokinetics 22.2% (2) |

| R1-R2 | 3 (3.0) | |||||||

| R1-R2-R3 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R1-R2-R4 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R1-R2-R3-R4 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R1-R3 | 2 (2.0) | |||||||

| R2 | 27 (27.3) | Part-time | 9 (9.1) | |||||

| R2-R3 | 10 (10.1) | |||||||

| R3 | 46 (46.5) | |||||||

| R4 | 5 (5.0) | |||||||

| Clinical trials(n = 95) | R1 | 15 (15.8) | 2 | 0.5–36 | 2.9 ± 5.2 | Full-time | 50 (52.6) | Prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients 22.2% (10);oncology pharmacy20% (9);outpatient pharmacy care 15.5% (7) |

| R1-R2 | 2 (2.1) | |||||||

| R1-R2-R3-R4 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R1-R3 | 2 (2.1) | |||||||

| R2 | 18 (18.9) | |||||||

| R2-R3 | 3 (3.2) | Part-time | 45 (47.4) | |||||

| R2-R3-R4 | 2 (2.1) | |||||||

| R3 | 38 (40.0) | |||||||

| R3-R4 | 3 (3.2) | |||||||

| R4 | 11 (11.6) | |||||||

| Administration and management (n = 95) | R1 | 8 (8.4) | 2 | 1–12 | 2.6 ± 2.2 | Full-time | 47 (49.5) | Prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients 43.7% (21)Stock management: 37.5% (18)Drug information: 10.4% (5) |

| R1-R2 | 2 (2.1) | |||||||

| R1-R2-R4 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R1-R3 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R2 | 11 (11.6) | |||||||

| R2-R3 | 1 (1.0) | |||||||

| R3 | 28 (29.5) | |||||||

| R3-R4 | 4 (4.2) | Part-time | 48 (50.5) | |||||

| R4 | 39 (41.0) | |||||||

| Drug evaluation and selection (n = 94) | R1 | 1 (1.1) | 3 | 1–48 | 4.0 ± 3.4 | Full-time | 31 (33.0) | Management 22.2% (14); Drug information 22.2% (14); Outpatient pharmaceutical care 14.3% (9) |

| R1-R2-R3 | 1 (1.1) | |||||||

| R2 | 13 (13.8) | |||||||

| R2-R3 | 3 (3.2) | |||||||

| R2-R3-R4 | 1 (1.1) | |||||||

| R3 | 38 (40.4) | Part-time | 63 (67.0) | |||||

| R3-R4 | 11 (11.7) | |||||||

| R4 | 21 (22.3) | |||||||

| Spread across residency | 5 (5.3) | |||||||

| Primary care (n = 99) | R1 | 4 (4.0) | 1 | 0.5–4 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | Full-time | 75 (96.1) | Prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients 66.7% (2);Quality management: 33.3% (1) |

| R2 | 11 (11.1) | |||||||

| R3 | 29 (29.3) | Part-time | 3 (3.8) | |||||

| R4 | 34 (34.3) | |||||||

| Not carried out. | 21 (21.2) | |||||||

SD, standard deviation; n, number of HPS responders; R1, first-year resident; R2, second-year resident; R3, third-year resident; R4, fourth-year resident.

Distribution of planned clinical rotations in Hospital Pharmacy Training Programme in Spain.

| Rotation by clinical areas | Number of hospitals (n = 99) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Infectious diseases | 70 | 70.7% |

| Haematology | 67 | 67.7% |

| Intensive Care Medicine | 66 | 66.7% |

| Internal Medicine | 64 | 64.6% |

| Emergency | 61 | 61.6% |

| Oncology | 60 | 60.6% |

| Paediatrics | 50 | 50.5% |

| Nephrology | 31 | 31.3% |

| Endocrinology and nutrition | 17 | 17.2% |

| Cardiology | 15 | 15.1% |

| Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation | 14 | 14.1% |

| Surgery | 12 | 12.1% |

| Geriatrics | 10 | 10.1% |

| Digestive | 6 | 6.1% |

| Pneumology | 6 | 6.1% |

| Long-term care centres | 5 | 5.0% |

| Psychiatry and Mental Health | 5 | 5.0% |

| Rheumatology | 4 | 4.0% |

| Neonatology | 3 | 3.0% |

| Neurology | 2 | 2.0% |

| Continuity of Care Unit | 2 | 2.0% |

| Solid organ transplants | 2 | 2.0% |

| Palliative care | 2 | 2.0% |

| Systemic/Immuno-mediated diseases | 2 | 2.0% |

| HIV | 1 | 1.0% |

| Haematological transplants | 1 | 1.0% |

| ASP | 1 | 1.0% |

| Home ospitalisation | 1 | 1.0% |

| Pharmacogenetics | 1 | 1.0% |

| Dermatology | 1 | 1.0% |

| Chronic patients | 1 | 1.0% |

| Allergy | 1 | 1.0% |

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; ASP, Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs.

Full-time rotations in most HPSs included primary care (96.1%), outpatient pharmaceutical care (90.9%), and oncology pharmacy (88.9%). Part-time rotations were less common than full-time ones and included drug information (78.3%), drug evaluation and selection (67.0%), and stock management (64.6%).

External rotations not included in the official specialty programme and elective rotationsA total of 93.9% (99) of the hospitals offered rotations not included in the official specialty training programme, most commonly carried out during the third and fourth years of residency (R3–R4) (69.95%), with a median duration of 8 weeks (range: 1–16), the most common being 4 weeks. Additionally, 91.2% (91) of the hospitals provided elective rotations, allowing residents to tailor their training according to personal interests, with a median duration of 8 weeks (range: 2–32).

Additional training: commissions, teaching, and researchIn 91.9% (91) of the hospitals, residents participated in clinical committees. A total of 95.9% (95) of the accredited units include in the educational itinerary the courses, master's programs, and conferences that residents are required to complete in order to finalize their training, with 91.9% (91) allowing attendance at courses aligned with their specific areas of interest. The mean number of classroom-based courses completed during the residency was 5.1 ± 2.6. A total of 22.2% (22) of hospitals included at least one master's degree in the training programme, while 9.1% (9) offered it as an optional component.

Regarding the doctorate, only 22.2% (22) of the hospitals had residents enrolled in a PhD at the time of the survey, although 46.5% (46) of HPS had tutors who held a doctoral degree (Table 2).

Supervision and evaluationIn 72.7% (72) of HPSs, tutor-resident meetings were held quarterly, while 20.2% (20) took place less frequently and 7.1% (7) more frequently.

A total of 98.0% (97) of departments provided residents with a training plan at the beginning of each academic year, which included different levels of responsibility in 78.8% (78) of cases.

Overall, 63.6% (6) of HPSs had a written general-supervision protocol for residents, but only 46.5% (46) had a specific supervision protocol for each rotation. With regard to on-call duties, 39.4% (39) of HPSs had a HPS protocol establishing supervision during these shifts.

In terms of evaluation, 65.6% (65) of departments reported using specific assessment tools. The teaching portfolio is the most frequently used, implemented in 45.4% of cases. Examinations were used in 22.2%, 360° evaluations in 19.2%, and audits and Mini-CEX (Mini Clinical Evaluation Exercise) in 7.1% and 6.1% of cases, respectively.

DiscussionThis is the first study to comprehensively map the organisation of hospital pharmacy residency training programmes in Spain. The high response rate (87%), with representation from all autonomous communities, provides a broad and reliable overview of the current training of hospital pharmacy residents. We did not analyse potential non-response bias (13% of the population), as we considered that there were no substantial differences between respondents and non-respondents. This assumption is supported by the descriptive nature of the study and the fact that it involved a finite population clearly defined by the Spanish Ministry of Health's teaching accreditation.

Our findings reveal considerable variability in the duration and organisation of rotations across hospitals, ranging from 1 to 12 months. Additionally, some hospitals do not define a fixed rotation schedule; instead, some training is spread across the residency period. This heterogeneity can be partly attributed to the use of shared or part-time rotations in many centres, which enables residents to train in multiple areas concurrently during the 4-year programme. The introduction of new fields5 such as pharmacogenetics and digital health, alongside the increase of accredited residency positions in some hospitals, may also be contributing to this variability.

The high proportion of part-time rotations—reported in over 60% of hospitals—reflects an evolution in HPSs towards a more integrated model of care. This contrasts with the traditional departmental structure,7 where, for instance, a pharmacist might have been exclusively assigned to parenteral nutrition. At present, many departments operate through teams that manage a patient's entire pharmacological treatment, promoting a more integrative model of care that may influence the organisation of rotations.7 Future research should investigate how this model affects both resident training outcomes and satisfaction, particularly when comparing full-time and part-time rotations.

In some hospitals, responses to questions about specific rotations were incomplete, or indicated that certain areas—such as prescription validation and drug dispensing for inpatients, or drug evaluation—are delivered longitudinally across the training period rather than within specific timeframes. In these cases, training is integrated into day-to-day clinical activities without a formally defined rotation. This is due to the decentralisation of these activities, and the training being organized across the 4-year residency period. Nonetheless, we believe that the acquisition of skills requires clearly defined objectives and a structured evaluation process to ensure consistent educational standards.8

The organisation of clinical rotations includes common areas such as infectious diseases, haematology, and oncology, but considerable variability exists in other areas. Similarly, although the training programme stipulates that clinical rotations should be carried out in the fourth year3, an increasing number of hospitals are distributing them across the entire residency period. This allows us to integrate them with non-clinical rotations, offering a more ongoing and cohesive learning experience. This reorganisation may be related to the growing involvement of hospital pharmacists in patient care teams,9–11 which facilitates residents' participation in clinical activities from the early stages of training. Such early engagement can help reinforce previously acquired knowledge and contribute to a more sustained and integrated development of clinical competencies.

Despite the fact that nearly 33% of hospitals currently provide pharmaceutical care in long-term care centres,9 the low rate of rotations in these settings is noteworthy. This is a particularly relevant issue, because regional pharmaceutical regulations are increasingly addressing the provision of care in long-term care centres in response to the growing needs of institutionalised patients.12–14

Rotation in primary care is already included in the training programme of nearly 80% of hospitals in Spain. This reflects ongoing changes in the role of hospital pharmacists, due to the increasing demand for pharmaceutical care able to support continuity of care across different levels of the healthcare system.15,16 It is essential to clearly define the skills to be acquired during primary care rotation and to formally incorporate it into the next version of the official specialty training programme.17

The considerable variability observed in our study highlights the urgent need to revise and update the hospital pharmacy training programme. Such a revision should reflect current professional practice and promote more consistent training that aligns with both present and future healthcare needs. The fact that 93% of hospitals offer rotations not included in the official programme underscores the relevance of incorporating emerging fields18 and transversal skills19 into the formal curriculum. To address this variability, the Tutors' Working Group is collaborating with other working groups within the SEFH to develop standardised, competency-based training models. These models will include recommendations on content, duration, and the appropriate year of residency for each rotation.20–24 These models aim to assist tutors in structuring resident training and minimising variability in rotation organisation.

Among the strengths of this study are a high participation rate and broad geographic representation, which together provide a reliable overview of the Spanish national scenario. One limitation, however, is that transversal skills were not assessed. These may already be incorporated in some hospitals and should be examined in future research to gain a more comprehensive understanding of current training practices. Furthermore, this study focused on the organisation and duration of rotations, without exploring how these are structured in each HPS in terms of defined competencies and the educational methods used to achieve them. Investigating these aspects could offer valuable insights and support greater consistency across training programmes.

In conclusion, this study highlights considerable variability in the organisation of training programmes across hospital pharmacy teaching units in Spain. Moving towards greater standardisation of rotations, the incorporation of transversal skills, and the revision of the national training programme are essential steps to ensure high-quality, equitable training that meets the demands of today's healthcare landscape.

Contribution to scientific literatureThis is the first study to describe the organisation of the training rotations of hospital pharmacy intern pharmacist residents (FIR) in Spain, providing a comprehensive view of the current situation in hospitals accredited for specialised health training.

The results obtained should be of great interest for hospital pharmacy tutors, since they can serve as a guide and reference for the organisation of the specific training itineraries of each HPS. This will contribute to promote a more homogeneous training aligned with the current needs of the specialty. Furthermore, our results show the need to update the training programme of the specialty and to move towards the standardisation of rotations, guaranteeing equitable training adapted to the current demands of hospital pharmacy.

CRediT authorship contribution statementClaudia Colomer Aguilar: Writing - review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Eva Negro-Vega: Writing - review & editing, Writing - original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Edurne Fernández de Gamarra-Martínez: Writing - review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Beatriz Martínez Castro: Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. María Pérez Abánades: Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Susana Redondo Capafons: Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Covadonga Pérez Menéndez Conde: Writing - review & editing, Writing - original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization.

FundingNone declared.

None declared.