To present the results of a survey about the Telemedicine outpatients experience and satisfaction of a pharmaceutical care program through Telepharmacy, carried out from hospital pharmacy departments in Spain during COVID-19 Pandemic (ENOPEX survey), and identify differences across regions in Spain.

MethodAn analysis of results of the national survey ENOPEX on outpatient Telepharmacy services during the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, analyzed by autonomous community in Spain. Data was collected in relation to point of delivery; pharmacotherapeutic follow-up; patient's opinion and satisfaction with Telemedicine; confidentiality; future development of pharmaceutical care, through Telepharmacy services; and coordination with the patient care team. Four multilevel regressions were performed to evaluate the differences between Spanish regions on the most relevant variables of the study, using the R version 4.0.3 software.

ResultsA total of 8,079 interviews were valid, 52.8% of respondents were female, age was 41-65 years in 54.3% of participants; 42.7% had been receiving treatment for more than 5 years; 42.8% lived 10-50 km from the hospital; the journey to hospital took more than one hour for 60.2% of participants. Globally, 85.7% received medicines at home. However, medicines were delivered at a community pharmacy in some communities, such as Cantabria (95.8%), or at primary care centers as in Castile La Mancha (16.5%). In total, 96.7% of participants were satisfied or very satisfied with Telemedicine pharmaceutical care, through Telepharmacy services, with differences across communities, with users in Andalusia reporting the highest satisfaction (OR = 1.58), and users in Castile-Leon being less satisfied with Telepharmacy services (OR = 0.66). Users in Catalonia are the ones more clearly in favor of Telemedicine pharmaceutical care, through Telepharmacy services as a complementary service, with an OR = 5.85 with respect to other users. The Telemedicine most frequently mentioned advantage was that Telepharmacy services avoided visits, especially in Cantabria (92.5%) and Extremadura (88.4%). Most patients prefer informed delivery of medicines at home when they do not have an appointment at the hospital: total of 75.6 %, from 50.1% of users in Cantabria to 96.3% in Catalonia (p < 0.001). The users less willing to pay for Telepharmacy services were the ones from Castile-Leon and Galicia, with users in Catalonia and Navarra showing higher willingness.

ConclusionsIn general terms, patients were satisfied with Telemedicine pharmaceutical care, through Telepharmacy services during the COVID-19 pandemic, being mostly in favor of maintaining these services to avoid travels.

Describir los resultados de la encuesta sobre experiencia y satisfacción de la Telemedicina en pacientes externos relativo a un programa de atención farmacéutica a través de la Telefarmacia, realizado desde los servicios de farmacia durante la pandemia COVID-19 (encuesta ENOPEX) e identificar las diferencias entre las comunidades autónomas de España.

MétodoSe analizaron los resultados de la encuesta nacional ENOPEX sobre Telefarmacia en pacientes externos durante el confinamiento debido a la pandemia COVID-19, realizado en las diferentes comunidades autónomas de España. Se recogieron datos relativos a lugar de entrega, seguimiento farmacoterapéutico, opinión y satisfacción del paciente con la Telefarmacia, confidencialidad, desarrollo futuro de la atención farmacéutica a través de los servicios de Telefarmacia, y coordinación con el equipo de atención al paciente. Se realizaron cuatro regresiones multinivel para evaluar las diferencias entre comunidades autónomas sobre las variables más relevantes del estudio por medio del software R versión 4.0.3.

ResultadosUn total de 8.079 entrevistas fueron válidas: el 52,8% eran mujeres, el 54,3% tenía entre 41-65 años, el 42,9% estaban en tratamiento desde hacía más de 5 años, el 42,8% vivía a 10-50 km del hospital y el 60,2% tardaba más de una hora en acudir al hospital. Globalmente, el 85,7% recibieron medicación a domicilio, aunque hubo comunidades autónomas en las que se optó también por las oficinas de farmacia, como en Cantabria (95,8%), o los centros de atención primaria, como en Castilla-La Mancha (16,5%). El 96,7% de los pacientes refirieron estar satisfechos o muy satisfechos con la Telemedicina en la atención farmacéutica mediante el uso de la Telefarmacia, detectándose variabilidad en cuanto a la opinión entre comunidades, desde la mejor opinión en Andalucía (odds ratio =1,58) y la menos favorable en Castilla y León (odds ratio = 0,66). Por su parte, Cataluña es la comunidad que estaría más claramente a favor de la Telemedicina en la atención farmacéutica de usar la Telefarmacia como actividad complementaria, con una odds ratio de 5,85 respecto al resto. Las ventajas más mencionadas de la Telemedicina fue que los servicios de Telefarmacia evitaban desplazamientos, especialmente en Cantabria (92,5%) y Extremadura (88,4%). Los pacientes mayoritariamente prefieren el acercamiento y entrega informada de la medicación a domicilio cuando no tienen que acudir al hospital, el 75,6% globalmente, desde el 50,1% de pacientes de Cantabria al 96,3% en Cataluña (p < 0,001). Las comunidades autónomas menos dispuestas a pagar por el servicio de Telefarmacia fueron Castilla y León y Galicia, y las que más, Cataluña y Navarra.

ConclusionesEn líneas generales, los pacientes están satisfechos con la Telemedicina aplicada a la atención farmacéutica a través de los servicios de Telefarmacia durante la pandemia COVID-19, estando mayoritariamente a favor de mantenerla para evitar desplazamientos.

National healthcare laws regulate drug dispensation in Spain and require that some therapeutic groups or medicines be dispensed at the Hospital Pharmacy (HP). This method ensures close monitoring of medicine use by a specialist pharmacist1–4, following the guidelines of the national projects of the Marco Estratégico de Atención a los Pacientes Externos (MAPEX)5 and the Capacidad-Motivación-Oportunidad (CMO)6 program of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH).

Technological advances have played a key role in facilitating Telemedicine7, which use has increased substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The declaration of the state of emergency in Spain8 led to an urgent amendment of national laws to permit the delivery of medicines to HP patients at home, community pharmacies, or primary care centers, to facilitate access to their medicines during the pandemic9. This scenario forced HPs in Spain to establish Telepharmacy services, which had never been available before, except in research studies. Telepharmacy users received their medicines at home, which spared them from traveling to the hospital, and allowed adequate remote pharmacotherapy follow-up. This phenomenon occurred worldwide10–14.

In May 2020, SEFH researchers conducted ad hoc interviews to assess the level of implementation and development of outpatient Telepharmacy services in HP in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic15. The survey involved 185 hospitals over the country. Notably, before the pandemic, Telepharmacy services involving home delivery of medicines were not available in 83.2% of HPs, whereas all HPs offered this service during the pandemic. Throughout the study period, 119,972 patients received their medicines remotely, and 134,142 deliveries were performed. Of the total number of participants, 87.6% had a teleconsultation prior to the delivery of medicines, and near 60% had the Telepharmacy activity recorded in their record of appointments. HPs most frequently offered informed home delivery of medicines, followed by delivery at the closest primary care center and community pharmacy. This information is essential for the future development of Telepharmacy after the pandemic. The results of this survey will help redesign Pharmacy Hospital pathways and activities in relation to Telepharmacy, following the current national laws in force.

The ENOPEX survey was conducted subsequently to the national Survey on the Situation of Telepharmacy in Spain16 (see interview script in Appendix 1) to poll the opinions and experiences of users of outpatient Telepharmacy services. To such purpose, we used an ad hoc questionnaire. A total of 9,442 questionnaires were distributed (8,079 were considered valid) among patients from 81 hospitals; 52.8% of respondents were female; age was 41-65 years in 54.3% of users; 42.7% had been receiving treatment for more than 5 years; 42.8 % lived 10-50 km from the hospital; and the journey to hospital took more than one hour for 60.2% of participants. The ENOPEX survey demonstrated that 96.7% of patients were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with Telepharmacy procedures. As many as 97.5% considered Telepharmacy as a complementary service to regular follow-up; 55.9% preferred face-to-face hospital pharmacy care if they have an appointment at the hospital; and 75.6% showed preference for receiving their medicines at home.

The main objective of this study is to report the results of the ENOPEX study through an analysis of the opinions and experiences of users of outpatient Telepharmacy services from a geographic perspective, and identify differences among autonomous communities.

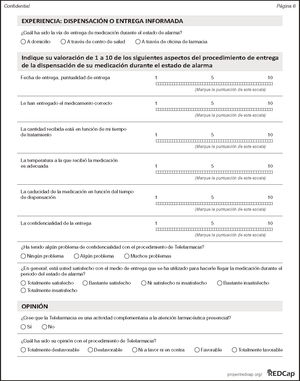

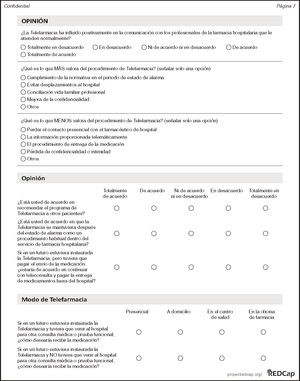

MethodsWe analyzed the results of the national survey ENOPEX16 by autonomous community. The survey involved users of outpatient Telepharmacy services during the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The data collected included point of delivery, pharmacotherapy follow-up, opinion on Telepharmacy, future development of Telepharmacy, confidentiality, satisfaction, and coordination with patient care teams. Participants were asked to answer the ENOPEX (see Appendix 1) questionnaire designed by a panel of HP experts in Telepharmacy.

SampleThe population of the study included adult (> 18 years) users of outpatient HP services in Spain, who voluntarily participated in the interview between March 15 and May 15, 2020. Prior informed consent was obtained either in written or telephonically.

Sample size was calculated based on a representative sample of 119,972 Telepharmacy users (data provided by the participating centers through a questionnaire about the situation of Telepharmacy services in Spain carried out by the SEFH some months before15). Sampling error was 99%, with a beta error of 20%. Twenty five percent of questionnaires were not returned.

Prior to the statistical analysis, sample size was calculated for a power of 80% (Cohen's coefficient). All statistical analyses were performed using the R software, assuming that 75% of subjects would be in favor of Telepharmacy services.

Calculations revealed that a sample of 16,588 users was required.

Data collectionEach participating center collected data based on the number of users to be recruited per hospital. Information was included on the online questionnaire available at (www.sefh.es). Study data were collected and provided using the TEDCap web application available on the SEFH server. Each center was assigned a unique code. Anonymization was performed through the allocation of an alphanumeric code for the identification of each recruited patient.

Questionnaires were completed anonymously in face-to-face visits, telephonically or online. Access to online questionnaires was given through a QR code. Express informed consent to participate in the study was requested on the first page of the questionnaire.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis included an initial collection of data, descriptive analysis of demographic characteristics, and an analysis of data related to questionnaire items, both globally and by autonomous community. Quantitative variables were expressed as means and standard deviations or as median values and quartiles in case of asymmetrical distribution. Qualitative variables were expressed as percentages. Comparison of quantitative variables across communities was performed using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Associations between independent qua litative variables were analyzed on the basis of contingency tables and residuals using Chi-square test or Monte Carlo methods and Fisher's exact test.

To assess the effect of autonomous community, four multilevel regressions were performed. This way, we analyzed user's acceptance of Telepharmacy as complementary to face-to-face hospital pharmacy care. Users’ willingness to pay for Telepharmacy services was also assessed. The four multilevel regressions were used as generalized mixed models adjusted for the maximum likelihood coefficient, Laplace approximation. Dependent variables were used following binomial distribution in the models for complementary service, satisfaction, and willingness to pay, and a linear regression model for the score given by users (1-10 points). Fixed effects are models identified as significant on bivariate analysis. Autonomous communities were introduced in random effects. All analyses were performed using the R software package version 4.0.3.

Ethical considerationsENOPEX was conducted in compliance with the international ethical standards for scientific research applicable to this type of study. The Spanish Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices of the Spanish Ministry of Health classified this study as a non post-authorization observational study in June 2020. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hospital Valme in Seville, on June 30, 2020 with code 1524-N-20.

Patients were identified with a code recorded on the Case Report Form, which guaranteed the confidentiality of data and preserved the identity of study participants. Once the inclusion phase was completed, data were anonymized and entered into specific biostatistical analysis programmes using the ID code initially assigned to each participant.

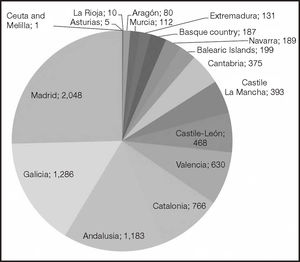

ResultsA total of 9,442 interviews were performed, of which 8,079 were considered valid (see Appendix 2 and Figure 1).

Eighty-one public and private hospitals of all levels of healthcare located in 16 of the 17 health systems in Spain took part in the study (Appendix 3).

Data from Asturias (5 patients), La Rioja (10 patients), Ceuta, and Melilla were excluded from analysis due to the small sample of patients.

Five autonomous communities represented 72% of patients; 25.3% of patients lived in the Community of Madrid, 15.9% in Galicia, 14.6% in Andalusia, 9.5% in Catalonia and 7.8% lived in the Autonomous Community of Valencia. Overall data by autonomous community are shown in Appendix 2.

Demographic data revealed that Extremadura and Aragón included more patients older than 41 years (88.9% and 87.5% respectively); Navarra and Catalonia showed a higher percentage of women (65.1% and 59.8% respectively).

There were a higher percentage of patients who had been on follow-up for more than 5 years in Murcia (66.1%) and Navarra (63.5%).

The autonomous communities with the highest number of patients living more than 10 km from the hospital were Andalusia (70.8%) and the Basque Country (64.2%).

The patients who had the longest journey to the HP lived in Andalusia and Aragón.

Finally, the highest percentage of employed patients was observed in Castile la Mancha (44.3%) and the Balearic islands (44.2%).

The methods of delivery differed across communities, ranging from home delivery only, as in the case of Navarra (100%), Extremadura (99.2%) or Galicia (99.1%) to other modalities involving informed delivery at a community pharmacy, as in Cantabria (95.8%). Some communities opted for mixed models, such as in the case of Andalusia, which offered delivery at home (67.3%), a community pharmacy (23.6%) or at the closest primary care center (9.1%) (Table 1). Confidentiality issues were reported by 5.8% of patients in Cantabria, whereas no reports were recorded in Andalusia, Basque Country, Galicia or Murcia (Table 1). Confidentiality issues were more frequent when the point of delivery was the community pharmacy (5.4%) vs home delivery (1.6%).

Experience with follow-up and dispensation/delivery by A.C

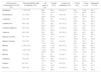

| Autonomous community | N = 8,079 (%) | Telepharmacy was useful to keep informed I agree or I totally agree (%%) | COVID-19-related questions solved I agree or totally agree (%) | Questions unrelated to COVID-19 solved I agree or I totally agree (%) | Home delivery n (%%) | Delivery at primary care center n (%) | Delivery at community pharmacy n (%) | No confidentiality problems n (%) | Satisfied with the method of delivery I agree or I totally agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Andalusia | 1,183 (100) | 1,006 (85.1) | 674 (82.4) | 960 (81.2) | 796 (67.3) | 108 (9.1) | 279 (23.6) | 1,183 (100.0) | 1,147 (97) |

| Extremadura | 131 (100) | 126 (96.3) | 88 (67.4) | 80 (61.2) | 131 (99.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 131 (99.5) | 130 (99.5) |

| Cantabria | 375 (100) | 285 (76.1) | 277 (73.9) | 239 (63.9) | 8 (2.1) | 6 (1.6) | 360 (95.8) | 353 (94.2) | 343 (91.6) |

| Castile-León | 468 (100) | 390 (83.4) | 400 (85.6) | 369 (78.9) | 438 (93.6) | 10 (2.1) | 20 (4.3) | 460 (98.5) | 450 (96.2) |

| Castile La Mancha | 393 (100) | 337 (85.9) | 339 (86.3) | 289 (73.6) | 328 (83.5) | 65 (16.5) | 0 (0.0) | 386 (98.4) | 381 (97.2) |

| Valencia | 630 (100) | 531 (84.3) | 555 (88.1) | 506 (80.4) | 630 (97.7) | 3 (0.5) | 12 (1.9) | 633 (98.2) | 623 (96.7) |

| Basque country | 187 (100) | 135 (72.2) | 80 (42.8) | 114 (61.0) | 185 (98.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 187 (100.0) | 168 (89.9) |

| Balearic Islands | 199 (100) | 168 (84.5) | 170 (85.5) | 169 (85.0) | 158 (79.4) | 32 (16.1) | 9 (4.5) | 202 (98.4) | 192 (96.8) |

| Madrid | 2,048 (100) | 1,812 (88.5) | 1,789 (87.4) | 1,701 (83.1) | 1,939 (94.7) | 23 (1.1) | 86 (4.2) | 1,933 (99.4) | 1,994 (97.4) |

| Galicia | 1,286 (100) | 1,127 (87.7) | 1,069 (83.2) | 978 (76.1) | 1,275 (99.1) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (0.9) | 1,286 (100.0) | 1,251 (97.3) |

| Murcia | 112 (100) | 103 (92.0) | 100 (89.3) | 91 (82.1) | 110 (98.2) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 112 (100.0) | 109 (97.5) |

| Catalonia | 766 (100) | 621 (81.2) | 645 (84.3) | 624 (81.5) | 658 (85.9) | 22 (2.9) | 86 (11.2) | 746 (97.5) | 736 (96.2) |

| Aragón | 80 (100) | 70 (87.6) | 73 (91.3) | 68 (85.0) | 78 (97.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.5) | 387 (98.5) | 381 (97.2) |

| Navarra | 189 (100) | 109 (58.2) | 93 (49.7) | 103 (55.0) | 189 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 186 (98.6) | 183 (97.1) |

In total, 71.6% of patients learned about the service of informed dispensation and delivery through direct information provided by the hospital pharmacist (from 88.1% of patients in Extremadura to 53.3% in Valencia). In 86.3 % of cases, a remote clinical follow-up consultation was held prior to the delivery of medicines (from 97.5% of patients in Aragón to 74.9% in the Basque Country).

As many as 6,915 patients (85.6%) stated that Telepharmacy helped them keep informed about their medications. By autonomous community (Table 1), we found that 58.2% and 72.2% of patients in Navarra and the Basque Country were satisfied with the Telepharmacy service, respectively, versus 96.3% and 92 % in Extremadura and Murcia, respectively.

As to whether they had been given the opportunity to make questions and/or solve doubts or resolve issues in relation to their medicines arising from the state of emergency, 91.3% of patients in Aragon answered “I agree” or “I totally agree” vs 42.8% of patients in the Basque Country. With regard to doubts or issues related to their medicines unrelated to the state of emergency, 85% of patients in Aragon answered “I agree” or “I totally agree” vs 55% of patients in Navarra.

In terms of general satisfaction, the communities with the lowest level of satisfaction (coefficient < 0) were Valencia (–0.14), Castile-León (–0.08) and Castile La Mancha (–0.10).

Informed drug deliveryA percentage of 85.8% of patients received their medicines at home, vs 10.8% of patients who received their medicines at a community pharmacy, and 3.4% who received them at their primary care center.

The autonomous communities with the highest level of satisfaction with the method of delivery (Table 1) were Murcia and Extremadura 97.5% and 99.5%, respectively, with patients living in the Basque Country and Cantabria showing the lowest level of satisfaction, 89.9% and 91.6%, respectively.

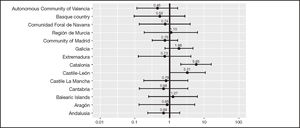

Acceptance as complementary procedureTelepharmacy was considered a complementary service to face-to-face hospital pharmacy (HP) care by 97.8% of patients. Acceptance ranged from 98.9% in the Basque Country to 95.4% in Catalonia or Castile La Mancha (Table 2). One of the factors with an independent effect on acceptance that Telepharmacy be considered a complementary service to face-to-face HP care included the time patients had been on follow-up by the HP. Thus, the longer the time on follow-up, the higher the acceptance that Telepharmacy is established as a complementary service. Other factors with independent effects were not having ever used a Telepharmacy service or having faced confidentiality issues. The time devoted to attend face-to-face visits negatively affects consideration of Telepharmacy as a complementary service. The autonomous communities most willing to use Telepharmacy as a complementary service included Catalonia and Castile-León, as compared to the other communities, OR = 5.85 and OR = 3.31, respectively (see Figure 2).

Opinions by A.C. about the most valued advantage, willingness to pay, en future method of delivery based on whether the patient has to visit the hospital or not.

| A.C. N= 8 079 (%) | Considers Telepharmacy complementary to face-to-face pharmacy care (%) | Favorable or totally favorable opinion with the Telepharmacy procedure (%) | Telepharmacy has improved communication with Hospital Pharmacy professionals I agree or I totally agree (%) | I would recommend the TP programm I agree or I totally agree (%) | I would maintain TP after the state of alarm I agree or I totally agree (%) | I most value that TP avoids travels (%) | Willingness to pain I agree or I totally agree (%) | If I visit the hospital in the future, I would like to receive face-to-face phamacy care (%%) | I I don't have to visit the hospital in the future, I would prefer receiving my medicines at home (%%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia 1,183 (14.6) | 1,160 (98.19) | 1,130 (95.69) | 883 (74.7) | 1,156 (97.8) | 1,129 (95.5) | 932 (78.8) | 557 (47.1) | 649 (54.9) | 709 (60.0) |

| Extremadura 131 (1.62) | 129 (98.5) | 130 (99.3) | 123 (94.0) | 131 (100.0) | 125 (95.5) | 121 (92.5) | 66 (50.8) | 115 (88.1) | 126 (96.3) |

| Cantabria 375 (4.6) | 371 (99.9) | 343 (91.6) | 259 (69.3) | 363 (96.8) | 354 (94.5) | 263 (70.3) | 163 (43.5) | 213 (57.0) | 187 (50.1) |

| Castile-León 468 (5.8) | 458 (98.0) | 317 (67.9) | 329 (70.5) | 354 (75.8) | 421 (90.1) | 326 (69.8) | 159 (34.1) | 297 (63.6) | 326 (69.7) |

| Castile La Mancha 393 (4.86) | 374 (95.4) | 366 (93.2) | 271 (69.2) | 312 (79.4) | 327 (83.4) | 278 (70.8) | 169 (43.2) | 204 (52.1) | 314 (80.1) |

| Valencia 630 (7.8) | 621 (98.6) | 598 (95.4) | 481 (76.5) | 611 (97.1) | 589 (93.5) | 503 (79.9) | 291 (46.2) | 279 (44.3) | 537 (85.3) |

| Basque Country 187 (2.3) | 184 (98.9) | 180 (96.7) | 132 (71.1) | 182 (97.4) | 170 (91.4) | 149 (80.2) | 80 (43.3) | 111 (59.4) | 143 (77.0) |

| Balearic Islands 199 (2.46) | 192 (96.6) | 179 (90.3) | 145 (73.2) | 185 (93.2) | 169 (85.0) | 138 (69.4) | 67 (33.8) | 97 (49.0) | 135 (68.0) |

| Madrid 2,048 (25.3) | 2,002 (97.8) | 1,941 (94.8) | 1,658 (81.0) | 1,986 (97.0) | 1,857 (90.7) | 1,470 (71.8) | 862 (42.1) | 1,146 (56) | 1,660 (81.1) |

| Galicia 1,286 (15.9) | 1,248 (97.1) | 1,237 (96.2) | 882 (68.6) | 1,221 (95.0) | 1,158 (90.1) | 938 (73.0) | 466 (36.3) | 712 (55.4) | 1,071 (83.3) |

| Murcia 112 (1.38) | 108 (97.3) | 105 (94.6) | 90 (80.4) | 107 (95.5) | 97 (86.6) | 79 (71.4) | 59 (52.7) | 54 (49.1) | 81 (73.2) |

| Catalonia 766 (9.48) | 95.4 | 724 (94.6) | 590 (77.1) | 743 (97.1) | 707 (92.3) | 533 (69.7) | 391 (51.1) | 425 (55.6) | 564 (73.7) |

| Aragón 80 (0.9) | 79 (98.8) | 79 (98.8) | 76 (95.1) | 77 (96.3) | 79 (98.8) | 63 (78.8) | 47 (58.8) | 22 (27.5) | 62 (77.5) |

| Navarra 189 (2.3) | 185 (98.4) | 174 (92.1) | 130 (68.8) | 186 (98.5) | 175 (92.6) | 167 (88.4) | 113 (60.3) | 141 (75.1) | 141 (75.1) |

TP: Telepharmacy.

In relation to the opinion of patients about the Telepharmacy procedures, 96.9% of users were “satisfied” or “very satisfied”, ranging from 99.3% in Extremadura to 67.9% in Castile-León.

Communication with the hospital pharmacist had improved with Telepharmacy, ranging from 94% of patients in Extremadura and 68.6% in Galicia.

In the multilevel regression model of opinion about Telepharmacy, having received medicines at home had positive independent effects. In contrast, not having had any contact with the hospital pharmacist before, being unemployed, and having had confidentiality problems had independent negative effects. In general, the community with the best opinions about Telepharmacy was Andalusia, contrasting with Castile-Leon.

For 81.5% of patients, the most valued advantage of Telepharmacy was not having to travel to the hospital, especially in Cantabria (92.5%) and the Basque Country (80.2%)

In total, 17.3% of patients found the disadvantage that Telepharmacy hindered face-to-face contact with a hospital pharmacist.

All patients in Extremadura would recommend the Telepharmacy program vs 75.8% of patients in Castile-León.

A percentage as high as 95.5% of patients in Andalusia and Extremadura vs 83.4% in Castile La Mancha would agree to maintaining the Telepharmacy service after the state of emergency.

Willingness to payThe factors with an independent positive effect on willingness to pay for Telepharmacy included living at a greater distance from the hospital and having received medicines at home or at a community pharmacy. In contrast, being 41-65 years old, having been more than 10 years on follow-up, being unemployed or a student, and having faced confidentiality issues had independent negative effects on willingness to pay for the service. The communities with the lowest willingness to pay were Castile-León OR = 0.7, the Balearic islands (OR = 0.76) and Galicia (OR = 0.65) vs Navarra (OR = 1.44), Aragón (OR = 1.25) and Catalonia (OR = 1.21), where patients exhibited a higher willingness to pay for the service.

All patients who had to visit the hospital preferred face-to-face dispensation, except for patients from Valencia (45.3%) and Aragon (56.3%), where the preferred option was informed delivery at home or at a close point of delivery.

When patients did not have to visit the hospital, the preferred option in all communities was home delivery, ranging from 50.1% in Cantabria to 96.3% in Extremadura.

DiscussionSince the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple Telepharmacy programs have been launched worldwide, as reported by Unni et al.17. In their review, Unnit described Telepharmacy initiatives launched over the world, which primarily involved remote consultation, home delivery of medicines, and patient education programs10,18–23. These initiatives provided valuable experiences and guidance for a proper, safe, effective, and efficient implementation of remote pharmacy care.

The Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency24,25 require that outcomes and patients’ experiences are evaluated. They advocate for a patient-centered model of shared decision-making to transition from models based on cost-effectiveness to value-based models26. In compliance with this mandate, this study describes the SEFH's ENOPEX study to evaluate the experiences of patients in Spain by autonomous community, in relation to pharmacotherapeutic follow-up, mode of dispensation, opinions about Telepharmacy, and validity of the questionnaire, as described by Margusino-Framiñán et al.16.

A thorough analysis by autonomous community reveals that the experience with Telepharmacy in terms of pharmacotherapeutic follow-up during the state of emergency was highly satisfactory for patients from all autonomous communities. Satisfaction was lower in relation to confidentiality, although confidentiality problems were not frequent. Ensuring the confidentiality of data during dispensing and home delivery of medicines is an important aspect of the SEFH Telepharmacy strategy and other international programs14,27. For instance, packets must be opaque, and the privacy of their contents must be guaranteed. Other recent initiatives also identify confidentiality as a point for improvement for the future development of Telepharmacy19,20. Hence, safety problems have been detected in some video conferencing platforms, which do not comply with HIPAA regulations in the USA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)28.

Patients were generally satisfied with Telepharmacy, although they considered it complementary to face-to-face hospital pharmacy care. The satisfactory experiences of patients with Telepharmacy offers the opportunity to improve their commitment and empowerment, which ultimately improves treatment adherence and clinical outcomes29,30.

In most autonomous communities, the model of remote informed delivery primarily involved home delivery of medicines, except for Cantabria, where medicines were mainly delivered at community pharmacies. This is relevant to the future standardization of Telepharmacy. This study reveals that patients prefer approximation and informed delivery of medicines when they do not have to visit the hospital, including patients in Cantabria. Telepharmacy reduces travels to hospital, prevents interference of treatment with daily life activity, involves cost savings, reduces the accumulation of medicines at home, is more convenient for the patient, and reduces dependence on caregivers14.

The survey documented that claims for confidentiality problems were 3.3 higher in the patients who collected their medicines at a community pharmacy vs those who received them at home. This may also explain patients’ preference for receiving medicines at home if they do not have to visit to the hospital.

In any case, patients should be offered several delivery options to discuss the best option in each case. This will be key to ensuring treatment adherence31. A recent small survey on 50 patients who collected their medicines at a community pharmacy during the COVID-19 in Spain32 revealed a high general satisfaction with the experience, with a mean score of 9.84 over 10. The broad collection times, convenience, and rapid service were some of the advantages reported by patients. Therefore, further research is required to identify the best methods of delivery in Telepharmacy.

Further evidence is necessary to measure the influence of Telepharmacy on clinical outcomes, and the cost-effectiveness of this service for patients and health systems. In this line, the randomized study conducted by Hefti et al.33 shows that the increase in the rate of hospitalizations during the COVID-19 pandemic was lower in patients who received Telepharmacy care between 2019 and 2020, as compared to a group without access to Telepharmacy (Telepharmacy group +12.9 % vs face-to-face group +40.2 %; p < 0.05), which resulted in savings of 1.57 million dollars.

Although it is out of the scope of this study, there are numerous reasons that explain that patients who received remote pharmacotherapy follow-up exhibited lower hospitalization rates. Pharmacotherapy care provided by pharmacists reduces adverse drug reactions, improves patient education, and enhances treatment adherence, thereby reducing admissions34–38.

The ENOPEX study provides guidance for future studies on Telepharmacy in relation to a correct pharmacotherapeutic follow-up.

One of the challenges to the provision of Telepharmacy services after the end of the pandemic is that legal guarantees at national and regional level are maintained. So far, laws supported the informed delivery of medicines9 at home or at the closest primary care center or community pharmacy, under the supervision of a hospital pharmacist.

The results of the ENOPEX survey are a starting point for each community to identify relevant variables to the classification of patients. These results will also help determine patient's preferences, which is essential to identify the patients who will benefit the most from Telepharmacy in the future, and the patients who need face-to-face pharmaceutical care. At national level, Margusino et al.16 detected five variables with independent effects on consideration of Telepharmacy as complementary to face-to-face pharmaceutical care, namely: time on follow-up, travel time to hospital, point of delivery, option of previous teleconsultation, and confidentiality during delivery.

Another relevant aspect is patients’ willingness to pay for Telepharmacy services. In this sense, patients in Navarra, Catalonia and Aragón were the most willing to pay for this service. For the sake of equity, this should not represent a barrier to remote delivery of medicines, although it reveals the relevance that patients give to Telepharmacy39,40.

The different studies and documents in relation to Telepharmacy conducted by the SEFH during the COVID-19 pandemic10,14–16 demonstrate that hospital pharmacies have the capacity to provide outpatient Telepharmacy services, as proven by the successful implementation of these services during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there is still room for improvement in the procedures. The SEFH is preparing seven methodological support documents, as follows: Guidelines on Telepharmacy for professions, Guidelines on Telepharmacy for patients, Effective and safe provision of Telepharmacy services, Validation of technological tools for Telepharmacy, prioritization of patients in Telepharmacy, guidelines for Telepharmacy consultation, and Indicators in Telepharmacy41.

A limitation of the ENOPEX survey is that a preliminary test was not performed to determine whether patients could understand, process, and answer the items of the questionnaire. In addition, participation in the study was not based on demographic or clinical criteria, but on willingness to take part, which may have resulted in a lack of geographical representativity. Nevertheless, a large sample was achieved, with patients from 16 of the 17 autonomous communities in Spain.

Although we did not reach the estimated sample size (16,588 interviews), 8,079 valid questionnaires were finally received, the sample is representative, and sample size does not affect the quality of the study.

The survey was conducted in the context of a pandemic and state of emergency, which may have influenced patients’ opinions.

The results of the ENOPEX survey on outpatient Telepharmacy services during the state of emergency demonstrate that patients from all autonomous communities were very satisfied with these services during the pandemic. Thus, most patients were in favor of maintaining these services to prevent travels to hospital and preferred receiving their medicines at home when they do not have an appointment at the hospital.

This study shows that patients consider outpatient Telepharmacy services as complementary to face-to-face pharmaceutical care. These services facilitate pharmacotherapeutic follow-up, patient education, coordination with the patient care team, and remote informed dispensing and delivery of medicines.

FundingNo funding.

AcknowledgementTo all co-investigators of the ENOPREX survey (Appendix 3).

Conflict of interestsNo conflict of interests.

| Autonomous Community N = 8 079 (%) | Telecansultatian priar ta delivery n (%) | > 40 years n (%) | Female n (%) | > 5 years on treatment n (%) | > 10 km n (%) | > 1 haur n < (%) | Emplayed n < (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 1,183 (100) | 998 (84.4) | 569 (46.0) | 569 (48.1) | 838 (70.8) | 1,022 (86.4) | 397 (33.6) |

| Extremadura | 131 (100) | 116 (88.9) | 60 (45.9) | 76 (57.8) | 70 (53.8) | 58 (44.4) | 35 (26.7) |

| Cantabria | 375 (100) | 308 (82.2) | 201 (53.5) | 130 (34.7) | 213 (56.7) | 162 (43.3) | 152 (40.4) |

| Castile-León | 468 (100) | 375 (80.2) | 248 (52.9) | 241 (51.5) | 169 (36.1) | 192 (41.0) | 204 (43.5) |

| Castile La Mancha | 393 (100) | 303 (77.0) | 217 (55.3) | 144 (36.6) | 128 (32.6) | 309 (78.5) | 174 (44.3) |

| Valencia | 630 (100) | 495 (78.5) | 353 (56.0) | 287 (45.5) | 403 (64.0) | 442 (70.1) | 240 (38.1) |

| Basque Country | 187 (100) | 153 (81.8) | 111 (59.4) | 75 (40.1) | 120 (64.2) | 96 (51.3) | 69 (36.9) |

| Balearic Islands | 199 (100) | 154 (77.3) | 112 (56.5) | 92 (46.4) | 126 (63.1) | 108 (54.4) | 88 (44.2) |

| Madrid | 2,048 (100) | 1,626 (79.4) | 1,106 (54.0) | 864 (42.2) | 770 (37.6) | 983 (48.0) | 893 (43.6) |

| Galicia | 1,286 (100) | 1,029 (80.0) | 642 (49.9) | 710 (55.2) | 738 (57.4) | 912 (70.9) | 520 (40.4) |

| Murcia | 112 (100) | 90 (80.4) | 66 (58.9) | 74 (66.1) | 70 (62.5) | 72 (64.3) | 27 (24.1) |

| Catalonia | 766 (100) | 597 (77.9) | 458 (59.8) | 470 (61.3) | 437 (57.0) | 470 (61.3) | 303 (39.5) |

| Aragón | 80 (100) | 70 (87.5) | 35 (43.8) | 28 (35.0) | 51 (63.7) | 67 (83.7) | 25 (31.3) |

| Navarra | 189 (100) | 159 (84.1) | 123 (65.1) | 120 (63.5) | 114 (60.3) | 134 (70.9) | 47 (24.9) |

| N° | AUTONOMOUS C. | Hospital | Name | Type of collaboration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andalusia | Agencia Sanitaria Costa del Sol | Begoña Tortajada Goitia | Co-investigator |

| 2 | Andalusia | Hospital de Poniente | Joaquín Urda Romacho | Principal Investigator |

| 3 | Andalusia | Hospital de Valme | Ramon A. Morillo Verdugo | Co-investigator |

| 4 | Andalusia | Hospital Juan Ramón Jimenez | M. de las Aguas Robustillo Cortés | Co-investigator |

| 5 | Andalusia | Hospital Punta de Europa | Ma Paz Quesada Sanz | Principal Investigator |

| 6 | Andalusia | Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar | M. Hosé Huertas Fernández | Principal Investigator |

| 7 | Andalusia | Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar | Rosa M. Ramos Guerrero | Co-investigator |

| 8 | Andalusia | Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena | Miguel Angel Calleja Hernández | Co-investigator |

| 9 | Andalusia | Hospital Virgen del Rocío | Trinidad Desongles Corrales | Co-investigator |

| 10 | Andalusia | Hospital San Juan de la Cruz | M. Teresa Ruiz-Rico Ruiz-Morón-NO SOCIA | Co-investigator |

| 11 | Aragón | Centro Neuropsiquiátrico N. S. del Carmen | Cristina Cirujeda | Principal Investigator |

| 12 | Aragón | Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa de Zaragoza | Mercedes Gimeno Gracia | Principal Investigator |

| 13 | Aragón | Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa de Zaragoza | Raquel Fresquet Molina | Co-investigator |

| 14 | Aragón | Hospital San Juan de Dios de Zaragoza | Alejandro J. Sastre Heres | Principal Investigator |

| 15 | Balearic Islands | Hospital de Manacor | M. Antonia Maestre Fullana | Co-investigator |

| 16 | Balearic Islands | Hospital Mateu Orfila | Gabriel Mercadal | Co-investigator |

| 17 | Balearic Islands | Hospital Universitario Son Espases | Ana Gómez Lobón | Co-investigator |

| 18 | Balearic Islands | Hospital Universitario Son Llàtzer | Joaquin Ignacio Serrano López de las Hazas | Principal Investigator |

| 19 | Cantabria | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla | David Gómez Gómez | Principal Investigator |

| 20 | Castile-León | Complejo Asistencial Soria | Maria Elisa Fernández García | Principal Investigator |

| 21 | Castile-León | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid | Encarnación Abad Lecha | Principal Investigator |

| 22 | Castile-León | Hospital de León | Ortega Valin, Luis | Principal Investigator |

| 23 | Castile-León | Santos Reyes | Virginia Benito Ibáñez | Principal Investigator |

| 24 | Castilla León | COMPLEJO ASISTENCIAL SORIA | María Elisa Fernandez García | Co-investigator |

| 25 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital de Guadalajara | Alicia Lázaro López | Co-investigator |

| 26 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital de Guadalajara | Clara Deán Barahona | Co-investigator |

| 27 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital de Guadalajara | Elvira Martínez Ruiz | Co-investigator |

| 28 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital de Guadalajara | Gema Isabel Casarrubios Lázaro | Co-investigator |

| 29 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital de Guadalajara | Inés Mendoza Acosta | Co-investigator |

| 30 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital de Guadalajara | Isabel María Carrión Madroñal | Co-investigator |

| 31 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital de Guadalajara | María Blanco Crespo | Co-investigator |

| 32 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital de Guadalajara | María Lavandeira Pérez | Co-investigator |

| 33 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital de Guadalajara | Patricia Tardáguila Molina | Co-investigator |

| 34 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital General La Mancha Centro | Beatriz Proy Vega | Principal Investigator |

| 35 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara | Ana M. Horta Hernández | Co-investigator |

| 36 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital Virgen de La Luz | Amparo Flor García | Co-investigator |

| 37 | Castile La Mancha | Hospital Virgen de La Salud | Araceli Fernández-Colada Sánhez | Principal Investigator |

| 38 | Catalonia | Durán y Reynals (Ico Hospitalet) | Eduardo Fort Casamartina | Co-investigator |

| 39 | Catalonia | Fundació Hospital Esperit Sant | Marcos López Novelle | Co-investigator |

| 40 | Catalonia | Fundació Hospital Esperit Sant | Miriam Maroto Hernando | Principal Investigator |

| 41 | Catalonia | Fundació Hospital Sant Joan de Deu Martorell | Ylenia Campos Baeta | Co-investigator |

| 42 | Catalonia | FUNDACIÓN SANITARIA DE MOLLET | Maria Priegue Gonzalez | Co-investigator |

| 43 | Catalonia | Fundación Sanitaria de Mollet | María Priegue González | Principal Investigator |

| 44 | Catalonia | Hospital Comarcal Blanes | Eva M. Martínez Bernabé | Co-investigator |

| 45 | Catalonia | Hospital General de Catalunya | Gemma Morla Clavero | Co-investigator |

| 46 | Catalonia | Hospital General de Granollers | Carlos Segui Solanes | Co-investigator |

| 47 | Catalonia | Hospital Infantil Vall d'Hebron | Aurora Fernández Polo | Co-investigator |

| 48 | Catalonia | HOSPITAL ST JAUME CALELLA | Nuria Sabate Frias | Co-investigator |

| 49 | Catalonia | Hospital Sta. Caterina | Magdalena Perpinya Gombau | Co-investigator |

| 50 | Catalonia | Hospital Sta. Caterina | Misael Rodriguez Goicoechea | Principal Investigator |

| 51 | Catalonia | Hospital Universitari de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta | Laura Viñas Sagué | Principal Investigator |

| 52 | Catalonia | Hospital Universitari Mutua Terrassa | Julia Pardo Pastor | Co-investigator |

| 53 | Catalonia | Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron (Traumatología) | Juan Carlos Juarez Gimenez | Co-investigator |

| 54 | Catalonia | Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron. Area General | Ignacio Cardona Pascual | Co-investigator |

| 55 | Catalonia | Hospital Universitario Sagrat Cor | Leticia Galofré Mestre | Principal Investigator |

| 56 | Catalonia | Ico Badalona | Cristina Ibáñez Collado | Principal Investigator |

| 57 | Catalonia | Institut Catalá d'oncologia de Girona | Nuri Quer Margall | Principal Investigator |

| 58 | Catalonia | Parc Tauli Sabadell | Belen López García | Co-investigator |

| 59 | Extremadura | Complejo Hospitalario Badajoz | Raquel Medina | Co-investigator |

| 60 | Galicia | Arquitecto Marcide-Prof Novoa Santos | Antonia Casas Martínez | Co-investigator |

| 61 | Galicia | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña | Luis Margusino Framiñán | Co-investigator |

| 62 | Galicia | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense | Belén Padrón Rodríguez | Co-investigator |

| 63 | Galicia | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela | M. Sol Rodríguez Cobos | Co-investigator |

| 64 | Galicia | Virxe Da Xunqueira | José Luis Rodríguez Sánchez | Co-investigator |

| 65 | La Rioja | Hospital San Pedro | Jara Gallardo Anciano | Principal Investigator |

| 66 | La Rioja | HOSPITAL SAN PEDRO | M. Carmen Obaldia Alaña | Co-investigator |

| 67 | Madrid | H. Infanta Leonor | Irene Cañamares Orbis | Co-investigator |

| 68 | Madrid | Hospital Clínico San Carlos | Ana García Sacristán | Co-investigator |

| 69 | Madrid | Hospital del Henares | M. Angeles Campos Fernández de Sevilla | Co-investigator |

| 70 | Madrid | Hospital del Tajo | Luis Pedraza | Co-investigator |

| 71 | Madrid | HOSPITAL EL ESCORIAL | Carolina Aguilar Guisado | Co-investigator |

| 72 | Madrid | HOSPITAL EL ESCORIAL | M. Isabel Barcía Martín | Co-investigator |

| 73 | Madrid | Hospital El Escorial | Susana Sánchez Suárez | Investigador Principal |

| 74 | Madrid | HOSPITAL GENERAL UNIVERSITARIO GREGORIO MARAÑÓN | Carmen Guadalupe Rodríguez Gonzalez | Co-investigator |

| 75 | Madrid | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón | Cecilia M. Fernández-Llamazares | Principal Investigator |

| 76 | Madrid | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón | Roberto Collado Borrell | Principal Investigator |

| 77 | Madrid | Hospital Ramon Y Cajal | M. de los Angeles Parro Martín | Co-investigator |

| 78 | Madrid | Hospital U. Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda | Amelia Sánchez Guerrero | Co-investigator |

| 79 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre | Marta González Sevilla | Co-investigator |

| 80 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada | Ana Ontañón Nasarre | Co-investigator |

| 81 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada | Belen Hernández Muniesa | Co-investigator |

| 82 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada | Carolina Mariño Martínez | Co-investigator |

| 83 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada | Cristina Bravo Lázaro | Principal Investigator |

| 84 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada | Mario García Gil | Co-investigator |

| 85 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada | Nuria Guerrero Muñoz | Co-investigator |

| 86 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario de Getafe | Alberto Onteniente González | Co-investigator |

| 87 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario de Getafe | Cristina Capilla Montes | Co-investigator |

| 88 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario de Getafe | Eva Negro Vega | Principal Investigator |

| 89 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario de La Princesa | Alberto Morell Baladron | Investigador Colaborador |

| 90 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario de Torrejón | Marta Blasco Guerrero | Principal Investigator |

| 91 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón | Patricia Sanmartin Fenollera | Co-investigator |

| 92 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario Hm Sanchinarro | Lara Martín Rizo | Investigador Principal |

| 93 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía | Cristina García Yubero | Co-investigator |

| 94 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario La Paz | Francisco Moreno Ramos | Co-investigator |

| 95 | Madrid | Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias | Marta Herrero Fernández | Co-investigator |

| 96 | Murcia | Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de La Arrixaca | Almudena Mancebo González | Co-investigator |

| 97 | Murcia | Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de La Arrixaca | Laura Menendez Naranjo | Co-investigator |

| 98 | Murcia | Hospital Comarcal del Noroeste | Isabel Susana Robles García | Co-investigator |

| 99 | Murcia | Hospital Reina Sofia de Murcia | María García Coronel | Co-investigator |

| 100 | Murcia | Hospital Universitario Los Arcos del Mar Menor María | Onteniente Candela | Co-investigator |

| 101 | Navarra | Clínica Universidad de Navarra | María Serrano Alonso | Co-investigator |

| 102 | Navarra | Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra | M. Teresa Sarobe Caricas | Co-investigator |

| 103 | Basque Country | Hospital de Urduliz- Alfredo Espinosa | M. Olatz Ibarra Barrueta | Co-investigator |

| 104 | Basque Country | Hospital Universitario Donostia | M. Asunción Aranguren | Co-investigator |

| 105 | Principado de Asturias | FUNDACIÓN HOSPITAL DE JOVE | Alba León Barbosa | Co-investigator |

| 106 | Valencia | Arnau de Vilanova-Lliria | M. Dolores Edo Solsona | Co-investigator |

| 107 | Valencia | Hospital General de Ontinyent | Ma Jose Martinez Pascual | Co-investigator |

| 108 | Valencia | Hospital General Universitario Castellón | Esther Vicente Escrig | Principal Investigator |

| 109 | Valencia | Hospital General Universitario de Alicante | Rosa Ruiz Fuster de Apodaca | Co-investigator |

| 110 | Valencia | Hospital General Universitario de Elx | Ana García Monsalve | Co-investigator |

| 111 | Valencia | Hospital Universitari I Politécnic La Fe | Emilio Monte Boquet | Principal Investigator |

| 112 | Valencia | Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset | Marta Hermenegildo Caudevilla | Co-investigator |