To identify sociodemographic, clinical, and pharmacological factors associated with nonadherence to antiretroviral treatment in patients with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome treated between 2017 and 2020 in four cities in Colombia.

MethodAn observational, cross-sectional, retrospective study was conducted of a population of patients with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome treated between 2017 and 2020. The Morisky-Green scale, the simplified medication adherence questionnaire, and the simplified scale to detect adherence problems to antiretroviral treatment were applied to determine patient adherence. A binomial multiple logistic regression was performed to evaluate the factors that best explain nonadherence.

ResultsA total of 9,835 patients were evaluated, of whom 74.4% were men, 71.1% were aged between 18 and 44 years, 76.0% had attended at most secondary school, 78.1% were single, and 97.6% resided in an urban area. After applying three different scales to each patient, 10% of the study population were identified as nonadherent to treatment. The risk of nonadherence was significantly higher in patients who presented any drug-related problem or had an adverse reaction to antiretroviral drugs.

ConclusionsThe variables most strongly associated with nonadherence to antiretroviral treatment were drug-related problems, adverse drug reactions, a history of nonadherence to treatment, and psychoactive substance use.

Identificar los factores sociodemográficos, clínicos y farmacológicos asociados a la no adherencia al tratamiento antirretroviral en pacientes con infección por virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana/sida atendidos entre 2017 y 2020 en diferentes ciudades de Colombia.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio observacional, de corte transversal y retrospectivo, con una población de pacientes con infección por virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana/sida atendidos entre 2017 a 2020. Se aplicaron las escalas Morisky-Green, el cuestionario simplificado de adherencia a la medicación y la escala simplificada para detectar problemas de adherencia al tratamiento antirretroviral, para determinar la adherencia de los pacientes. Se realizó una regresión logística múltiple para evaluar los factores que mejor explican la no adherencia.

ResultadosSe evaluaron 9.835 pacientes, de los cuales el 74,4% eran hombres, el 71,1%% tenían una edad entre 18 a 44 años, el 76,0% cursó como máximo hasta secundaria, el 78,1% eran solteros y el 97,6% residían en zona urbana. Se encontró una proporción de no adherencia al tratamiento del 10% después de aplicar tres escalas diferentes a cada paciente. Las personas que presentaron algún problema relacionado con los medicamentos tuvieron un riesgo significativamente mayor de no ser adherentes, al igual que aquellos que tuvieron alguna reacción adversa a los medicamentos antirretrovirales.

ConclusionesLos problemas relacionados con el uso de medicamentos, las reacciones adversas a medicamentos, los antecedentes de no adherencia al tratamiento y el consumo de sustancias psicoactivas fueron las variables que más se asociaron con la no adherencia al tratamiento antirretroviral.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) continues to be a global public health problem. According to figures provided by the World Health Organization (WHO), at the end of 2018, there were approximately 38 million people with HIV. Over time, this disease has claimed more than 32 million lives1. Human immunodeficiency virus is a chronic infection. Resources are aimed at increasing its prevention and improving access to health care. Its control at the individual level depends largely on adherence to antiretroviral treatment (ARV)2,3.

According to the WHO, and based on the definitions of Haynes and Rand4 adherence to treatment can be understood as “The degree to which a person’s behaviour (taking medication, following a diet, and making lifestyle changes) corresponds to the recommendations agreed upon by a health care provider”. In HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients, the rapid rate of virus replication and mutation requires high adherence to drug treatment to reduce the viral load and ensure that drug therapy is effective3,5.

ARV treatment is the most effective intervention in terms of survival and reduced morbidity and mortality in HIV patients6. However, a significant percentage of patients still present virological treatment failure7,8, mainly due to nonadherence to therapy. Adherence to ARV treatment can be affected by multiple factors. Several studies have shown how these factors can vary according to the population in which they are studied. In general, low adherence to ARV treatment has been found to be associated with variables such as low educational levels, sexual orientation (homosexual), age (younger people), low income, unemployment, and time on treatment9,10. Similarly, associations have been found between nonadherence to ARV treatment and the use of psychoactive substances such as cannabis, cocaine, methadone, heroin, and alcohol10,11.

In Colombia, the Ministry of Social Protection and Health affirms that pharmaceutical chemists are responsible for evaluating and monitoring adherence to ARV; however, no specific methodology has been defined12 and pharmacists are responsible for measuring adherence by using different methodologies, such as questionnaires/scales and dispensing records13.

Variability in the factors that lead to nonadherence to ARV treatment makes it relevant to evaluate these factors in specific populations and thus identify and focus health interventions on those aspects that can have a positive impact on adherence, thus improving health outcomes for patients.

The objective of this study was to identify the sociodemographic, clinical, and pharmacological factors associated with nonadherence to ARV treatment in HIV patients treated in health care provider institutions in Colombia.

MethodsAn observational, cross-sectional, retrospective study was conducted of patients diagnosed with HIV. Between 2017 and 2020, the study included patients with active ARV treatment who had agreed to participate in a pharmacotherapeutic follow-up program in a Colombian health institution in the cities of Medellin, Cali, Bogota, and Barranquilla. We excluded minors when the individuals responsible for them did not authorize participation in the pharmacotherapeutic follow-up program.

During the pharmacotherapeutic follow-up consultation, pharmacists measured adherence in each patient by administering the Morisky-Green scale14, the Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire (SMAQ)15, and the simplified scale to detect problems with adherence (ESPA) to ARV treatment16. After completing the three scales, patients with a result of nonadherence on at least one of the scales were nonadherent. Three different scales were used to measure adherence to reduce potential information bias because experience has indicated that patients tend to memorize the questionnaires and respond intuitively.

A database was used to include and store the variables identified during the medical and pharmaceutical consultations regularly attended by patients. For the purposes of analysis, these variables were first grouped into sociodemographic ones, such as age, sex, educational level, marital status, area of residence, occupation, economic dependence, health regime, sexual preference, children and partner, and socioeconomic level. The latter variable was measured according to housing conditions and environment on a scale of 1 to 6 as defined by the National Administrative Department of Statistics of Colombia, where 1 indicates the worst conditions and 6 is the best conditions. We also included clinical variables (stage at admission, psychoactive substance use, psychological illnesses, emergencies in the last year) and pharmacological variables (time on treatment, ARV regimen, a history of nonadherence, adverse drug reactions [ADRs], polymedication, and drug-related problems [DRPs]). Definitions provided by the WHO were used to classify ADRs. The identification and classification of DRPs and their interventions were based on the Dader method, which defines DRPs as negative clinical outcomes resulting from pharmacotherapy that for many reasons lead to the nonachievement of the therapeutic objective or to the appearance of unwanted effects.

We conducted a univariate analysis. Qualitative variables are expressed as absolute and relative frequencies (simple and cumulative) and quantitative variables are expressed as summary measures, such as central tendency, dispersion, and position (Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test). We performed contingency tables and the chi-square test and used Odds Ratios (OR) and their respective 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) to measure statistical power.

The variables that showed statistical differences in the bivariate analysis were entered into a multivariate model for explanatory purposes (binary logistic regression: 95% confidence interval; alpha = 0.05). R statistical software was used.

As stated in Act No. 260 of June 2, 2021, this study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Human Research of University CES. It was also endorsed by the Scientific Management of the insurer and the research committee of the health institution.

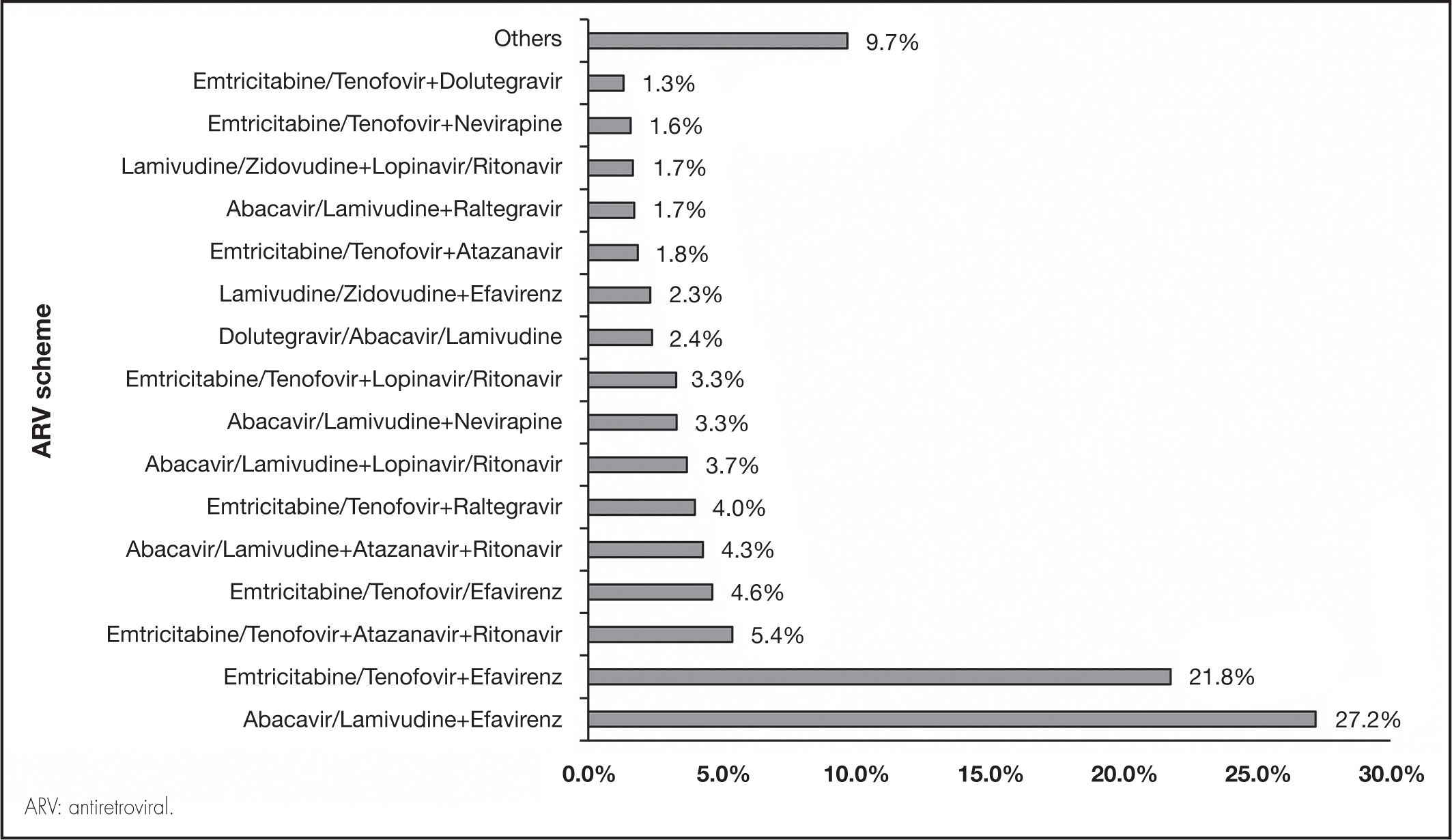

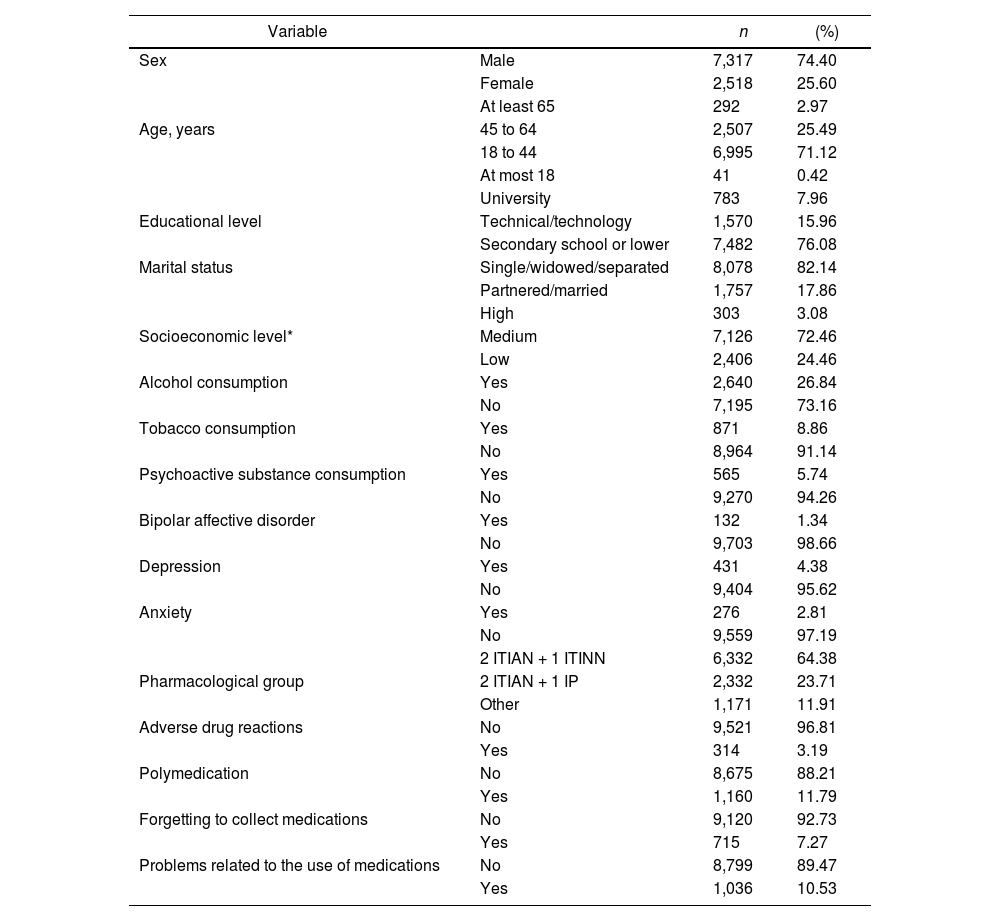

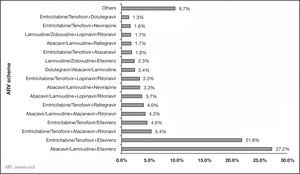

ResultsThe analysis included a total of 9,835 patients with HIV/AIDS on ARV treatment. Of these patients, 74.4% were men, 71.1% were between 18 and 44 years of age, 76.0% had at most secondary education, 78.1% were single, 97.6% resided in urban areas, 72.4% had a medium socioeconomic level (levels 3 and 4), and 82.1% did not have an active partner. Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics of the study population. Most patients received the ARV treatments abacavir/lamivudine plus efavirenz (27.2%) and emtricitabine/tenofovir plus efavirenz (21.8%). Figure 1 shows the different treatments in the study population.

General characteristics of the HIV patient population on antiretroviral treatment (2017-2020)

| Variable | n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 7,317 | 74.40 |

| Female | 2,518 | 25.60 | |

| At least 65 | 292 | 2.97 | |

| Age, years | 45 to 64 | 2,507 | 25.49 |

| 18 to 44 | 6,995 | 71.12 | |

| At most 18 | 41 | 0.42 | |

| University | 783 | 7.96 | |

| Educational level | Technical/technology | 1,570 | 15.96 |

| Secondary school or lower | 7,482 | 76.08 | |

| Marital status | Single/widowed/separated | 8,078 | 82.14 |

| Partnered/married | 1,757 | 17.86 | |

| High | 303 | 3.08 | |

| Socioeconomic level* | Medium | 7,126 | 72.46 |

| Low | 2,406 | 24.46 | |

| Alcohol consumption | Yes | 2,640 | 26.84 |

| No | 7,195 | 73.16 | |

| Tobacco consumption | Yes | 871 | 8.86 |

| No | 8,964 | 91.14 | |

| Psychoactive substance consumption | Yes | 565 | 5.74 |

| No | 9,270 | 94.26 | |

| Bipolar affective disorder | Yes | 132 | 1.34 |

| No | 9,703 | 98.66 | |

| Depression | Yes | 431 | 4.38 |

| No | 9,404 | 95.62 | |

| Anxiety | Yes | 276 | 2.81 |

| No | 9,559 | 97.19 | |

| 2 ITIAN + 1 ITINN | 6,332 | 64.38 | |

| Pharmacological group | 2 ITIAN + 1 IP | 2,332 | 23.71 |

| Other | 1,171 | 11.91 | |

| Adverse drug reactions | No | 9,521 | 96.81 |

| Yes | 314 | 3.19 | |

| Polymedication | No | 8,675 | 88.21 |

| Yes | 1,160 | 11.79 | |

| Forgetting to collect medications | No | 9,120 | 92.73 |

| Yes | 715 | 7.27 | |

| Problems related to the use of medications | No | 8,799 | 89.47 |

| Yes | 1,036 | 10.53 |

TIAN: Nucleotide analogue reverse-transcriptase inhibitor; ITINN: non-nucleotide reverse-transcriptase inhibitor; IP: protease inhibitor.

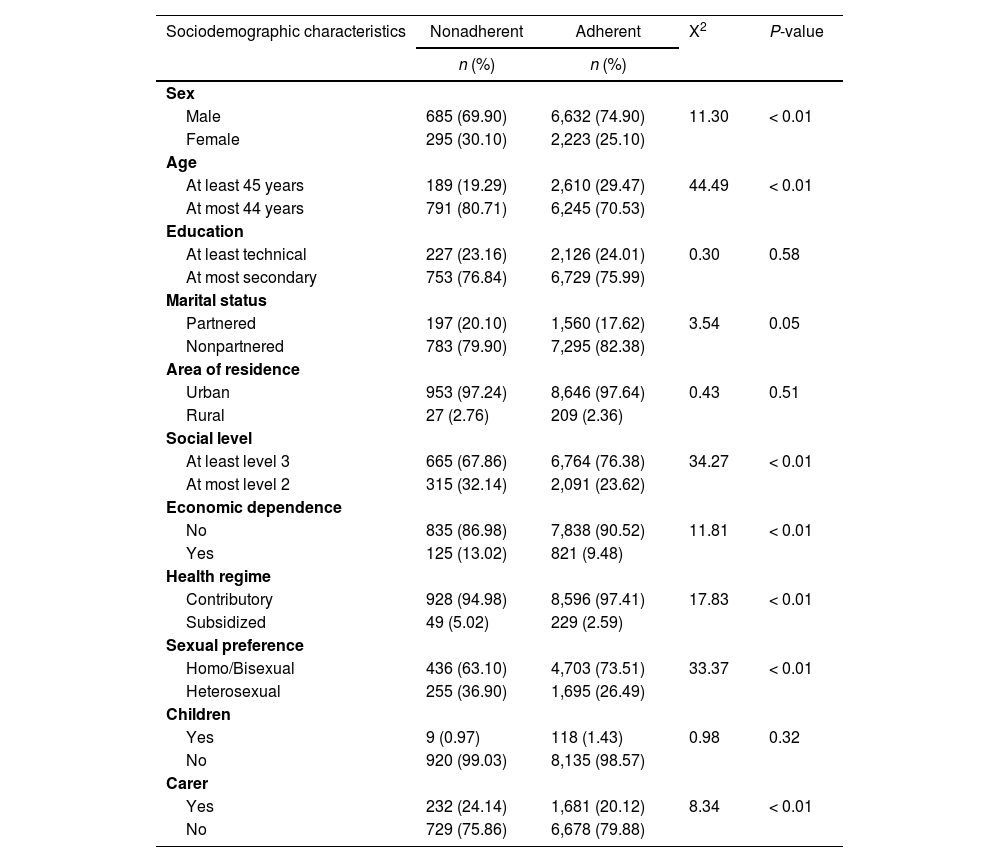

In total, 10.0% of patients were classified as nonadherent. This population was sociodemographically characterized by being male (69.9%), less than 45 years of age (80.7%), without a partner (79.9%), having a medium socioeconomic level of at least 3 (67.9%), being economically independent (87.0%), affiliated to the contributory health regimen (95.0%), and having homo/bisexual sexual tendencies (63.1%) (Table 2).

Sociodemographic characteristics associated with nonadherence in HIV patients on antiretroviral treatment (2017-2020)

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Nonadherent | Adherent | X2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 685 (69.90) | 6,632 (74.90) | 11.30 | < 0.01 |

| Female | 295 (30.10) | 2,223 (25.10) | ||

| Age | ||||

| At least 45 years | 189 (19.29) | 2,610 (29.47) | 44.49 | < 0.01 |

| At most 44 years | 791 (80.71) | 6,245 (70.53) | ||

| Education | ||||

| At least technical | 227 (23.16) | 2,126 (24.01) | 0.30 | 0.58 |

| At most secondary | 753 (76.84) | 6,729 (75.99) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Partnered | 197 (20.10) | 1,560 (17.62) | 3.54 | 0.05 |

| Nonpartnered | 783 (79.90) | 7,295 (82.38) | ||

| Area of residence | ||||

| Urban | 953 (97.24) | 8,646 (97.64) | 0.43 | 0.51 |

| Rural | 27 (2.76) | 209 (2.36) | ||

| Social level | ||||

| At least level 3 | 665 (67.86) | 6,764 (76.38) | 34.27 | < 0.01 |

| At most level 2 | 315 (32.14) | 2,091 (23.62) | ||

| Economic dependence | ||||

| No | 835 (86.98) | 7,838 (90.52) | 11.81 | < 0.01 |

| Yes | 125 (13.02) | 821 (9.48) | ||

| Health regime | ||||

| Contributory | 928 (94.98) | 8,596 (97.41) | 17.83 | < 0.01 |

| Subsidized | 49 (5.02) | 229 (2.59) | ||

| Sexual preference | ||||

| Homo/Bisexual | 436 (63.10) | 4,703 (73.51) | 33.37 | < 0.01 |

| Heterosexual | 255 (36.90) | 1,695 (26.49) | ||

| Children | ||||

| Yes | 9 (0.97) | 118 (1.43) | 0.98 | 0.32 |

| No | 920 (99.03) | 8,135 (98.57) | ||

| Carer | ||||

| Yes | 232 (24.14) | 1,681 (20.12) | 8.34 | < 0.01 |

| No | 729 (75.86) | 6,678 (79.88) | ||

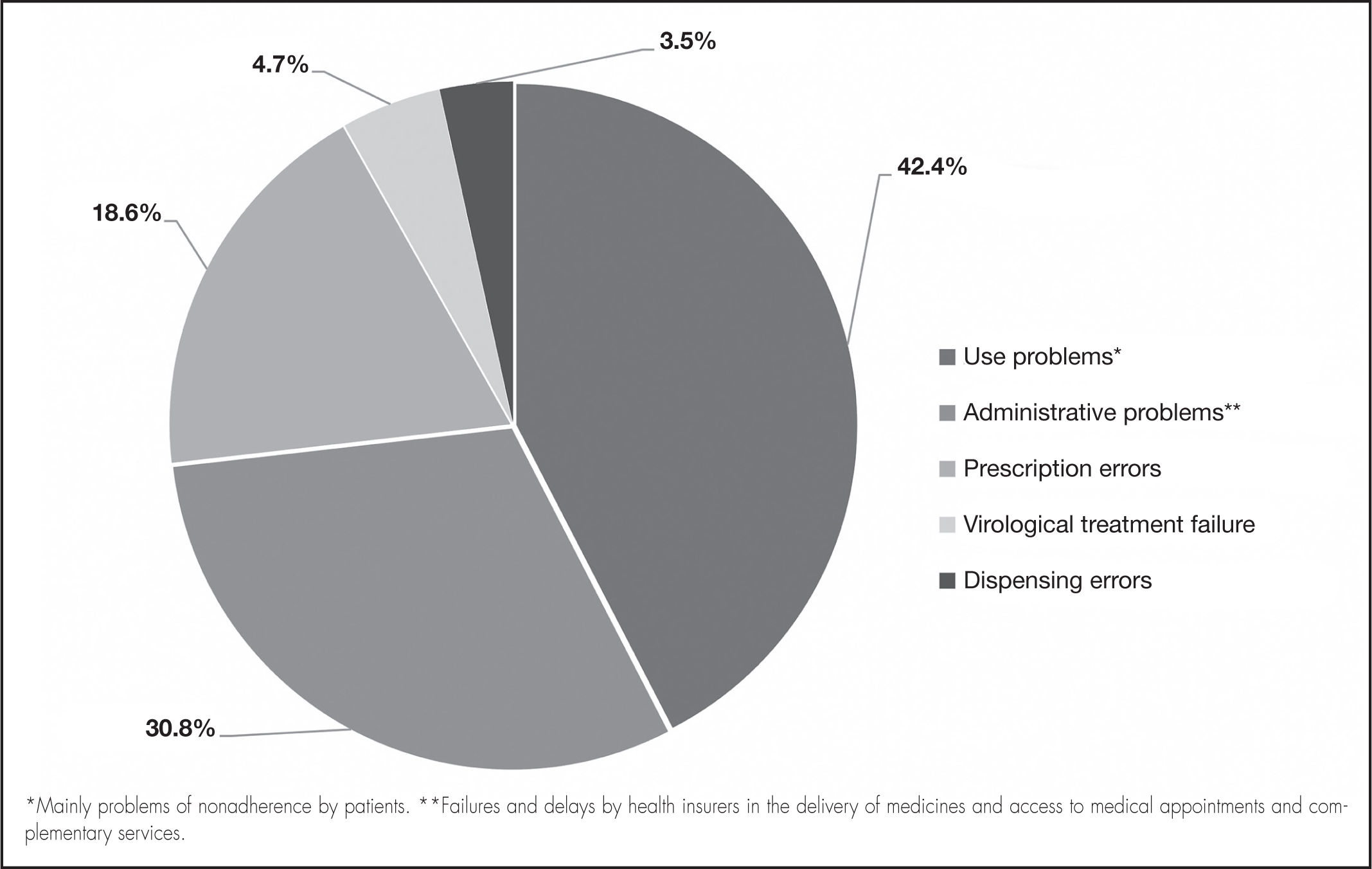

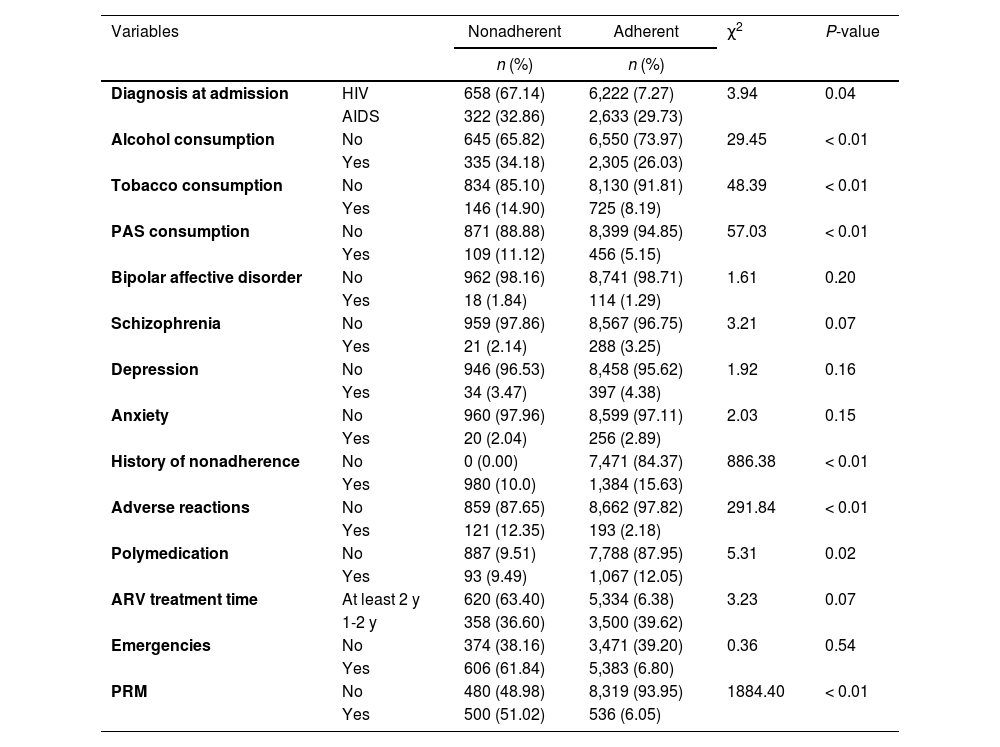

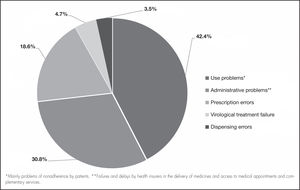

Regarding the clinical and pharmacological variables, the nonadherent patients differed in terms of having an HIV diagnosis (not yet classified as AIDS) at admission (67.1%), not consuming alcohol (65.8%), not smoking tobacco (85.1%), and denying the consumption of psychoactive substances (88.9%). Of the nonadherent patients, 100% had a history of nonadherence, 50% had presented with medication-related problems (Figure 2), and 12.4% had presented with adverse reactions (Table 3).

Clinical and pharmacological characteristics associated with nonadherence in HIV patients on antiretroviral treatment (2017-2020)

| Variables | Nonadherent | Adherent | χ2 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Diagnosis at admission | HIV | 658 (67.14) | 6,222 (7.27) | 3.94 | 0.04 |

| AIDS | 322 (32.86) | 2,633 (29.73) | |||

| Alcohol consumption | No | 645 (65.82) | 6,550 (73.97) | 29.45 | < 0.01 |

| Yes | 335 (34.18) | 2,305 (26.03) | |||

| Tobacco consumption | No | 834 (85.10) | 8,130 (91.81) | 48.39 | < 0.01 |

| Yes | 146 (14.90) | 725 (8.19) | |||

| PAS consumption | No | 871 (88.88) | 8,399 (94.85) | 57.03 | < 0.01 |

| Yes | 109 (11.12) | 456 (5.15) | |||

| Bipolar affective disorder | No | 962 (98.16) | 8,741 (98.71) | 1.61 | 0.20 |

| Yes | 18 (1.84) | 114 (1.29) | |||

| Schizophrenia | No | 959 (97.86) | 8,567 (96.75) | 3.21 | 0.07 |

| Yes | 21 (2.14) | 288 (3.25) | |||

| Depression | No | 946 (96.53) | 8,458 (95.62) | 1.92 | 0.16 |

| Yes | 34 (3.47) | 397 (4.38) | |||

| Anxiety | No | 960 (97.96) | 8,599 (97.11) | 2.03 | 0.15 |

| Yes | 20 (2.04) | 256 (2.89) | |||

| History of nonadherence | No | 0 (0.00) | 7,471 (84.37) | 886.38 | < 0.01 |

| Yes | 980 (10.0) | 1,384 (15.63) | |||

| Adverse reactions | No | 859 (87.65) | 8,662 (97.82) | 291.84 | < 0.01 |

| Yes | 121 (12.35) | 193 (2.18) | |||

| Polymedication | No | 887 (9.51) | 7,788 (87.95) | 5.31 | 0.02 |

| Yes | 93 (9.49) | 1,067 (12.05) | |||

| ARV treatment time | At least 2 y | 620 (63.40) | 5,334 (6.38) | 3.23 | 0.07 |

| 1-2 y | 358 (36.60) | 3,500 (39.62) | |||

| Emergencies | No | 374 (38.16) | 3,471 (39.20) | 0.36 | 0.54 |

| Yes | 606 (61.84) | 5,383 (6.80) | |||

| PRM | No | 480 (48.98) | 8,319 (93.95) | 1884.40 | < 0.01 |

| Yes | 500 (51.02) | 536 (6.05) | |||

ARV: antiretroviral; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PAS: psychoactive substances; PRM: problems related to medication.

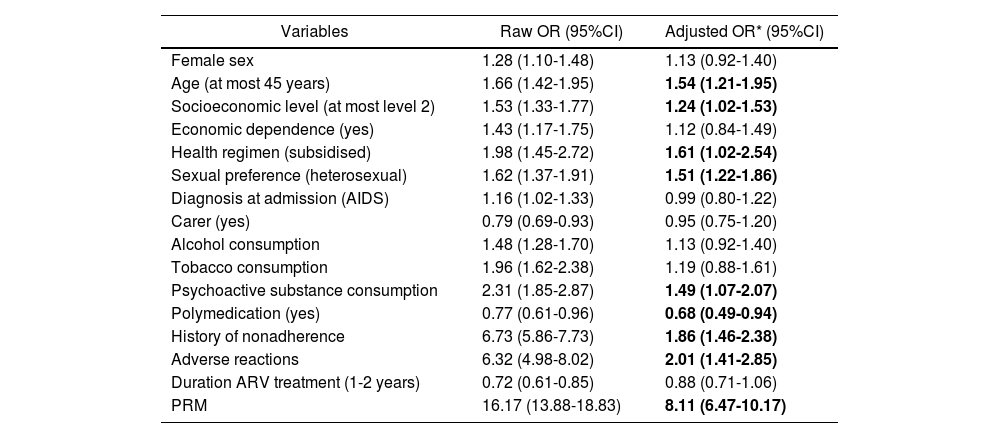

The multivariate analysis found significant associations between nonadherence and DRPs, ADRs, a history of nonadherence, health affiliation regime, age (at most 45 years), sexual preference (heterosexual), psychoactive substance use, socioeconomic level (2 or lower), and polymedication. The latter variable was a “protective factor” for adherence (adjusted OR: 0.68; CI: 0.49–0.94). Of note, Table 4 shows that the ratio of nonadherence to adherence is 8 times higher in patients with DRPs than in those without DRPs (adjusted OR: 8.11; CI: 6.47–10.17). Adverse reactions and history of nonadherence also acted as risk factors (adjusted OR: 1.86; CI: 1.46–2.38 and adjusted OR: 2.01; CI: 1.41–2.85, respectively).

Variables that explain nonadherence in patient with HIV/AIDS under antiretroviral treatment (2017-2020)

| Variables | Raw OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR* (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 1.28 (1.10-1.48) | 1.13 (0.92-1.40) |

| Age (at most 45 years) | 1.66 (1.42-1.95) | 1.54 (1.21-1.95) |

| Socioeconomic level (at most level 2) | 1.53 (1.33-1.77) | 1.24 (1.02-1.53) |

| Economic dependence (yes) | 1.43 (1.17-1.75) | 1.12 (0.84-1.49) |

| Health regimen (subsidised) | 1.98 (1.45-2.72) | 1.61 (1.02-2.54) |

| Sexual preference (heterosexual) | 1.62 (1.37-1.91) | 1.51 (1.22-1.86) |

| Diagnosis at admission (AIDS) | 1.16 (1.02-1.33) | 0.99 (0.80-1.22) |

| Carer (yes) | 0.79 (0.69-0.93) | 0.95 (0.75-1.20) |

| Alcohol consumption | 1.48 (1.28-1.70) | 1.13 (0.92-1.40) |

| Tobacco consumption | 1.96 (1.62-2.38) | 1.19 (0.88-1.61) |

| Psychoactive substance consumption | 2.31 (1.85-2.87) | 1.49 (1.07-2.07) |

| Polymedication (yes) | 0.77 (0.61-0.96) | 0.68 (0.49-0.94) |

| History of nonadherence | 6.73 (5.86-7.73) | 1.86 (1.46-2.38) |

| Adverse reactions | 6.32 (4.98-8.02) | 2.01 (1.41-2.85) |

| Duration ARV treatment (1-2 years) | 0.72 (0.61-0.85) | 0.88 (0.71-1.06) |

| PRM | 16.17 (13.88-18.83) | 8.11 (6.47-10.17) |

ARV: antiretroviral; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; PRM: problems related to medication.

In total, 10% of the study population were identified as nonadherent. This percentage is lower than the percentages reported by Sung-Hee Kim et al.17 (47%, 38%, and 33% in North America, Europe, and South America, respectively). However, it should be noted that most of the studies referred to in their work used viral load and dispensing records to measure adherence. Although some of the scales used to measure adherence have not been validated in HIV patients, it should be noted that they are widely used given the high cost or lack of availability of other methods18.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 53 studies conducted in Latin America and the Caribbean19 showed that overall adherence to treatment was 70%: thus, the percentage of nonadherent patients was higher in those studies than in our study. Suárez et al.20 evaluated adherence to ARV treatment in patients in the Caribbean region of Colombia. They used the Morisky-Green test as a measure and found that 89.0% were nonadherent. Adherence levels are highly variable and depend mainly on the population studied (variability between regions) and the measurement instrument used21.

The presence of adverse reactions represents a strong barrier to adherence to ARV treatment. Associations were found between nonadherence to ARV therapy and adverse drug reactions and DRPs. These results are consistent with recent findings obtained by Urizar et al.22, who found that patients receiving ARV treatment in a hospital in Paraguay were eight times more likely to be nonadherent to treatment when adverse reactions occurred. Similarly, Pérez and Viana23 found that the risk of nonadherence to ARV treatment was four times higher in patients who had adverse drug reactions.

In this study, DRPs were the most relevant factor associated with nonadherence. This result is significant given that few studies have evaluated the association between nonadherence to ARV treatment and the presence of DRPs. In general, the most frequently evaluated variable has been the presence of adverse drug reactions; however, Ospina et al.24 conducted a review in 2011 and found that, regarding medication, safety problems (including adverse drug reactions) only form a small percentage of all the potential problems that can occur during medication use.

Overall, the available evidence suggests that treatment adherence worsens as the number of pills the patients must take increases25. According to our results, and contrary to expectations, it is striking that polymedication (taking more than five drugs, including ARVs) was found to be a protective factor for adherence. The reasons for this situation remain unclear; however, polymedicated patients are generally older, which may explain adherence in this group of patients.

Significant associations were also found between nonadherence and other sociodemographic factors (being less than 45 years of age and low income). The results suggest that young people are at increased risk of nonadherence. This situation may be related to social behaviour and the young patients’ environment, which may be less strict in terms of the importance of adherence to taking medications. This result is very similar to that found in a systematic review conducted by Ghidei et al.26, who found that older patients were at a lower risk of nonadherence. Income level is widely recognized as a factor that can act as a strong barrier to patient access to medical appointments and medications9–11.

In Colombia, people access health services through affiliation with the General Social Security Health System. In 2018, according to data provided by the national health survey, 93.5% of Colombians were affiliated with the system: 58.0% were affiliated through the contributory regimen (employed people contribute resources to the health system) and the remaining 42.0% were affiliated through the subsidized regimen (unemployed people receive coverage by the state)27. The affiliation regimen is related to the income of the individuals; in general, people affiliated with the subsidized regimen have scarce economic resources and are not actively employed. According to our results, there is an association between being affiliated with the subsidized regimen and an increased risk of nonadherence to treatment. This may be explained by the relationship between the affiliation regimen and the lack of formal work and scarce economic resources.

The results also suggest that adherence to medication is lower in heterosexual patients than in homo/bisexual patients. It remains unclear if there is an association between sexual preference and an increase in nonadherence. Neupane et al.28 found that adherence was higher among women than among men (OR: 10.5; CI: 1.8–60.1), although no association was found with sexual preference.

No differences in adherence were found between people who consumed alcohol and tobacco (after multivariate analysis); however, an association was found between the consumption of psychoactive substances and nonadherence to ARV treatment. These results differ from those obtained by Velloza et al.29, who conducted a systematic review and found that patients who consumed alcohol were at a higher risk of nonadherence (OR: 2.47; CI: 1.58–3.87). Similar results were obtained by González-Álvarez et al.30 They found that the risk of nonadherence was higher among alcohol-consuming patients (OR: 4.33; CI: 1.16–16.21), whereas they found no differences in adherence among cocaine-, cannabis- and heroin-consuming patients.

These disparities in the results may be due to differences and variability in the dynamics of the consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and psychoactive substances among the study populations. It may be the case that the percentage of alcohol and tobacco use is higher than that reported in the study, given that patients may avoid providing information that they feel is inappropriate to disclose to their treating physicians.

It is noteworthy that a history of anxiety and depression appeared to be factors associated with adherence, although without reaching statistical significance. This result contrasts with those found in a systematic review conducted in India10, which found that patients with depressive symptoms were at an increased risk of nonadherence to ARV treatment. It is noteworthy that no information was included on the level of control of psychological disorders in the study patients, given that the management or otherwise of these comorbidities directly affects adherence to ARV treatment.

Other results suggest that patients who have previously been assessed as nonadherent are more likely to be associated with new nonadherence behaviour. According to the results shown in Table 4, patients who at some points have been assessed as nonadherent are almost twice as likely to continue to present adherence problems in the future.

Finally, it is important to highlight the diversity of factors that can lead to inadequate adherence to ARV treatment. There is a need for comprehensive management and interventions directed at modifiable variables and at patients who are at increased risk of nonadherence, with pharmaceutical education being a high priority given the impact of adverse drug reactions and the need for the prevention of DRPs.

This study has some limitations. The three scales used to measure levels of adherence are indirect methods and there will always be a risk that patients, in the attempt to avoid stigmatization, will answer the questions based on what they consider to be the most appropriate response. It would have been useful to have incorporated other types of measurement, such as dispensing records and cross-checking them against the qualitative results of adherence to further ensure that patients classified as nonadherent are in fact nonadherent. On the other hand, there may have been information bias regarding some relevant variables, such as alcohol, tobacco, and psychoactive substance use, because there is always a risk that patients may fail to provide adequate information, especially when, in this case, such information was collected during the normal care process rather than during a study.

In conclusion, the variables that were most strongly associated with nonadherence to ARV treatment were DRPs, adverse drug reactions, a history of nonadherence to treatment, and psychoactive substance use.

FundingNo funding.

AcknowledgmentsWe would like to thank Helpharma and the health care sponsor for their support and access to the information needed to conduct the study.

Conflicts of interestNo conflicts of interest.

Contribution to the scientific literatureThis study provides new information by analysing variables derived from pharmacotherapeutic follow-up and their relationship with nonadherence —such as problems related to medication— and integrates these variables into a multivariate model that includes other social, demographic, and clinical factors.

The results may help in the development of interventions to prevent and manage nonadherence to antiretroviral treatment in a population of almost 10,000 patients with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. They may also open the door to designing a predictive model of nonadherence, which will help to improve health outcomes in the population studied and apply timely interventions in nonadherent patients. Thus, it will be possible to avoid the negative clinical outcomes associated with nonadherence, such as virological treatment failure and resistance to antiretroviral drugs.

Early Access date (10/26/2022).