Analyze scientific literature on qualitative research that studies the medication experience—MedExp—and related pharmaceutical interventions that bring changes in patients' health. Through the content analysis of this scoping review, we intend to: (1) understand how pharmacists analyze the MedExp of their patients who receive Comprehensive Medication Management CMM and (2) explain which categories they establish and how they explain the individual, psychological, and cultural dimensions of MedExp.

MethodsThe scoping review followed recommendations from PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews. Medline (Pubmed), SCOPUS, Web of Science, and Psycinfo were used to identify research on MedExp from patients attended by pharmacists; and that they comply with quality standards, Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research. Articles published in English and Spanish were included.

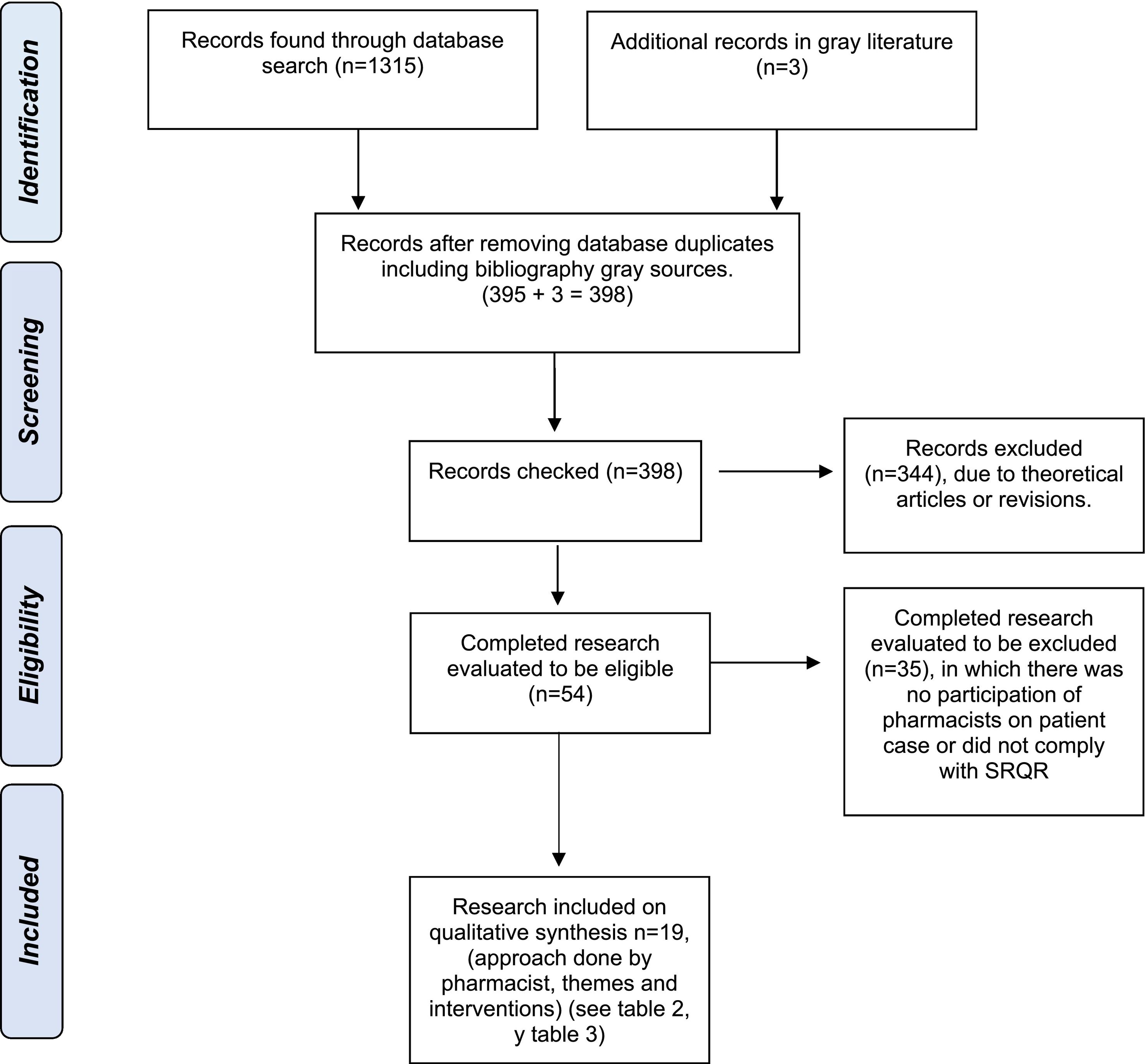

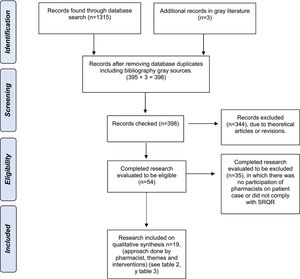

Results395 qualitative investigations were identified, 344 were excluded. In total, 19 investigations met the inclusion criteria. Agreement between reviewers, kappa index 0.923, 95% CI (0.836–1.010).

The units of analysis of the patients' speeches were related to how they were progressing in their medications and how it was built through MedExp, the influence it has on the experience of becoming ill, the connection with socioeconomic aspects, and beliefs. Based on MedExp, the pharmacists raised cultural proposals, support networks, health policies, and provide education and information about medication and disease. Additionally, characteristics of the interventions were identified, such as a dialogic model, therapeutic relationship, shared decision-making, comprehensive approach, and referrals to other professionals.

ConclusionsThe MedExp is an extensive concept, which encompasses people's life experience who use medications based on their individual, psychological, and social qualities. This MedExp is corporal, intentional, intersubjective, and relational, expanding to the collective because it implies beliefs, culture, ethics, and the socioeconomic and political reality of each person located in their context.

Analizar la literatura científica sobre investigaciones cualitativas que estudian la experiencia con la medicación -MedExp- y las intervenciones farmacéuticas relacionadas que aportan cambios en la salud de pacientes. A través del análisis de contenido de esta revisión de alcance se pretende (1) comprender cómo analizan los farmacéuticos la MedExp de sus pacientes que reciben Comprehensive Medication Management (CMM) y (2) explicar cuáles categorías establecen y cómo explican las dimensiones individuales, psicológicas y culturales de MedExp.

Métodosla revisión de alcance siguió las recomendaciones PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews. Se hizo una búsqueda en Medline (Pubmed), SCOPUS, Web of Science y Psycinfo para identificar investigaciones sobre MedExp de pacientes atendidos por farmacéuticos; y que cumplieran con estándares de calidad, Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research. Se incluyeron artículos publicados en inglés y español.

ResultadosSe identificaron 395 investigaciones cualitativas, se excluyeron 344. En total 19 investigaciones cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión. Concordancia entre los revisores, índice de kappa 0,923, IC 95% (0,836-1,010).

Las unidades de análisis de los discursos de los pacientes se relacionaron con una construcción de la MedExp en el transitar de las personas con sus medicamentos, la influencia que tiene en la experiencia de enfermar, la conexión con aspectos socioeconómicos, y las creencias. A partir de la MedExp, los farmacéuticos plantearon propuestas culturales, redes de apoyo, a nivel de políticas sanitarias, y brindar educación e información acerca de la medicación y enfermedad. Adicionalmente, se identificaron características de las intervenciones como modelo dialógico, relación terapéutica, toma de decisiones compartidas, abordaje integral y derivaciones a otros profesionales.

ConclusionesLa MedExp es un concepto extenso, que abarca la experiencia vivida de las personas que utilizan medicamentos partiendo de sus cualidades individuales, psicológicas y sociales. Esta MedExp es corporal, intencional, intersubjetiva y relacional, ampliándose a lo colectivo porque implica las creencias, la cultura, la ética y la realidad socioeconómica y política de cada persona situada en su contexto.

Aunque se vive individualmente, la experiencia con la medicación es colectiva y requiere un enfoque relacional para realizar prácticas clínicas contextualizadas.

Implicaciones de los resultados obtenidosComprender la experiencia con la medicación permite brindar intervenciones farmacéuticas contextualizadas, mejorando la salud de cada paciente.

IntroductionThe expression “medication experience” (MedEx) has emerged in the context of Comprehensive Medication Management (CMM). The term was first coined by Cipolle et al.1–3 as the lived experience of patients with their medications, which shapes their attitudes, beliefs, and preferences in relation to medication and determines their behavior when taking medication. To develop this concept, the same authors1 resorted to terms from the field of medical anthropology, such as illness narratives described by Kleinman.4 This expression explains how patients express and understand illness. The authors also consider the link described by Brown et al.5 between behavior and illness experience, i.e., the experience of being ill. Thus, the authors translated these concepts into pharmaceutical care and examined whether ideas about disease, feelings, and clinician's expectations, along with the effects of disease on patient's functionality may directly influence MedExp. As stated by Good,6 “the experience, suffering, distress, and perils that threat people” are a subject of study of medical anthropology. Thus, qualitative studies are conducted on “human experience and the existential ground of culture” take theoretic frameworks from social sciences “to comparatively analyze disease and healthcare practices”, including CMM. Based on this humanistic approach, Cipolle et al.1,2 argue that patients have stories to tell health professionals, who can learn much from patients. Narratives are a major source of information that should be the core of pharmacotherapy history and could be used to design pharmacy care plans.6,7

Qualitative studies consider that experience is communicated in the language of culture, patient's symptoms are coded in cultural language and the “primary interpretative task of the clinician is to decode patient's symbolic expressions”.6 According to these 2 approaches, understanding MedExp will help incorporate into CMM practices the bodily phenomena linked to sociocultural phenomena that patients experience when their illnesses are treated with medications. This approach will help professionals adopt a holistic strategy for the development of personalized solutions to pharmacotherapy-related problems. In clinical pharmacy practice, Shoemaker et al.8 and Ramalho-de-Oliveira et al.9 recognize the relationship between MedExp and pharmacotherapy problems. MedExp has also been analyzed from a phenomenological perspective6,10,11 based on existential categories such as time, space, relationships with others, and sexuality, which are integral to the lived body.10,12 Silva-Castro13 considers that it is necessary that the pharmacist adopts this perspective. This way, the pharmacist will understand how patients make decisions when taking their medications, their actual behaviors, along with bodily, social, and political expressions concerning “the experiential dimension of human suffering”. The author states that it is necessary to contextualize each MedExp in patient's culture to obtain clinical outcomes that improve the health of people.14

When pharmacists engage in patient care through CMM, MedExp serves as a link, since it involves examining pharmacy interventions qualitatively, in terms of patient's beliefs, understanding of medication, preferences, concerns, and behaviors.15 Interestingly, the first principle proposed by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society to help patients make the most of medicines was Medicines Optimization.16 In the same line, Schommer et al.17 note that clinicians' perception of diagnosis, drug-therapy decision-making, and risk weighting may differ from patient's perceptions. Thus, the authors highlight the relevance of understanding patient's MedExp in their context to determine their preferences as to medications. Machuca18 adds that MedExp depends on patient's ability to process data and absorb information and on interaction with their sociocultural and political environment. When contextualizing the situation of a patient to improve their MedExp, Viana et al.19 remark that MedExp is crucial in decision-making, as it is often expressed as an understanding and concern regarding medication. Care should be taken not to judge the attended person when assessing their experience.

Now, we understand the relevance of adopting a humanistic approach in pharmacy practices through the analysis of medication experience. The aim of this review was to understand how the pharmacists who provide CMM services assess MedExp in their patients. We also analyzed the categories established in pharmaceutical interventions and how individual, psychological, and cultural dimensions of MedExp are explained. The objective of this study was to perform a review of the literature on MedExp and the related interventions that generate a change in the health of patients receiving pharmaceutical care.

MethodsDesignA scoping review was conducted based on PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines (PRISMA-ScR).20 The purpose was to identify, select, analyze, and summarize qualitative studies on the MedExp of patients attended by healthcare teams that included a pharmacist.

Selection criteriaA selection was performed of qualitative studies that complied with Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR).21 Studies based on qualitative and ethnographic techniques were also included. Works only focused on quantifying adherence and assessing medication errors or side effects were excluded. Studies available in languages other than English or Spanish were excluded.

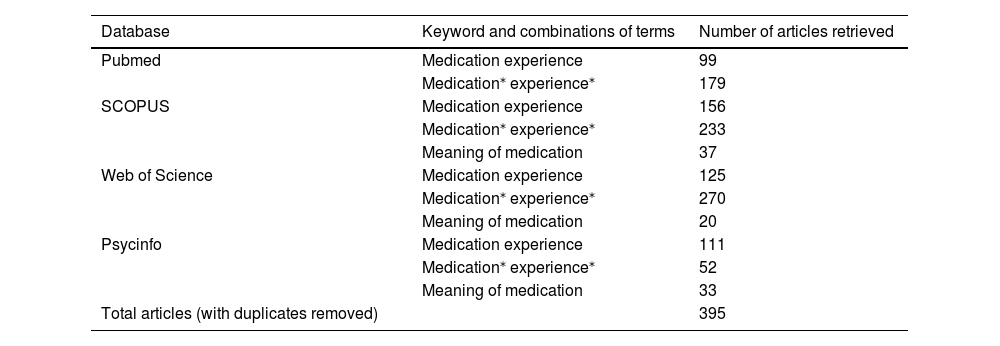

Information and search sourcesA literature search was conducted of articles published before October 30, 2021 using Medline (Pubmed), SCOPUS, Web of Science, and Psycinfo. The same keywords were used on all databases (Table 1), except for Medline (Pubmed), where the MeSH term meaning of medication was not included owing to the document noise it generated. The MeSH term qualitative research, or the Boolean operator AND, were not used due to the high amount of articles retrieved. We used the asterisk (*) to extend search using alternative words.

Database search strategy.

| Database | Keyword and combinations of terms | Number of articles retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| Pubmed | Medication experience | 99 |

| Medication⁎ experience⁎ | 179 | |

| SCOPUS | Medication experience | 156 |

| Medication⁎ experience⁎ | 233 | |

| Meaning of medication | 37 | |

| Web of Science | Medication experience | 125 |

| Medication⁎ experience⁎ | 270 | |

| Meaning of medication | 20 | |

| Psycinfo | Medication experience | 111 |

| Medication⁎ experience⁎ | 52 | |

| Meaning of medication | 33 | |

| Total articles (with duplicates removed) | 395 |

Additionally, 3 studies22–24 were identified in gray literature not indexed in the databases searched. Meta synthesis25 (indexed in databases) included 3 articles26–28 not indexed in our databases.

Study selectionStudy selection was performed by 2 pharmacists. Controversies and methodological concerns were solved by the author, who is a pharmacist and an anthropologist.

Data collectionAbstracts were first reviewed to preliminarily apply inclusion/exclusion criteria. Then, potentially eligible studies underwent full-text reading. Information was entered onto an MS Excel® spreadsheet, including authors, country, participant profiles, qualitative techniques used, diseases, SRQR quality parameters (supplementary material available at: https://www.sfthospital.com/documents/articles/farmhosp2023_orozcosilvamachuca_experienciamedicacion_tabla1_SRQR.pdf), emergent themes on medication experience, the interventions proposed, and representative narratives.

Information collection and synthesisInformation was collected in relation to MedExp and the interventions that could drive a change in patient's health. Patient narratives on their beliefs and MedExp were identified.

ResultsStudy selection and data collectionCategorization of studies is shown in Fig. 1.

Study selection flowchart based on Prisma Extension for Scoping Reviews.20

Kappa index was 0.923 (0.836–1.010), which indicates a very good interrater reliability (supplementary material available at: https://www.sfthospital.com/documents/articles/farmhosp2023_orozcosilvamachuca_experienciamedicacion_tabla2_kappa.pdf).

Quality assessmentThe 19 studies included complied with most of the SRQR quality recommendations for qualitative studies.21 In some studies, limited information is provided on the context where interaction with patients occurred, which makes it more difficult to define patient profile. Several studies were conducted in the hospital setting, where semi-structured interviews were most frequently used. However, unlike in-depth interviews, semi-structured interviews do not provide a detailed insight into the context of the patient. Participant observation, taken from ethnographic studies, by which researchers visit the communities where medications are used also provides valuable information about routine practices. Regarding the reliability and validity of the studies included, reflexibility was poorly presented in the studies. Seven studies were complied with this item.23,29,30–34 Limitations were described in some studies25,29,31–33,35–42 and two35,36 studies do not detail the technique used to validate their findings. As a constructive criticism, most of the studies do not adopt a gender-based approach43,44 when analyzing narratives. Indeed, several studies do not explain the reason why the gender of their respondents is not reported. Other limitations have been identified regarding cross-sectional issues45 such as race, ethnicity, migration, poverty, social class, and health inequalities, which were considered in a limited number of studies.29,31,46

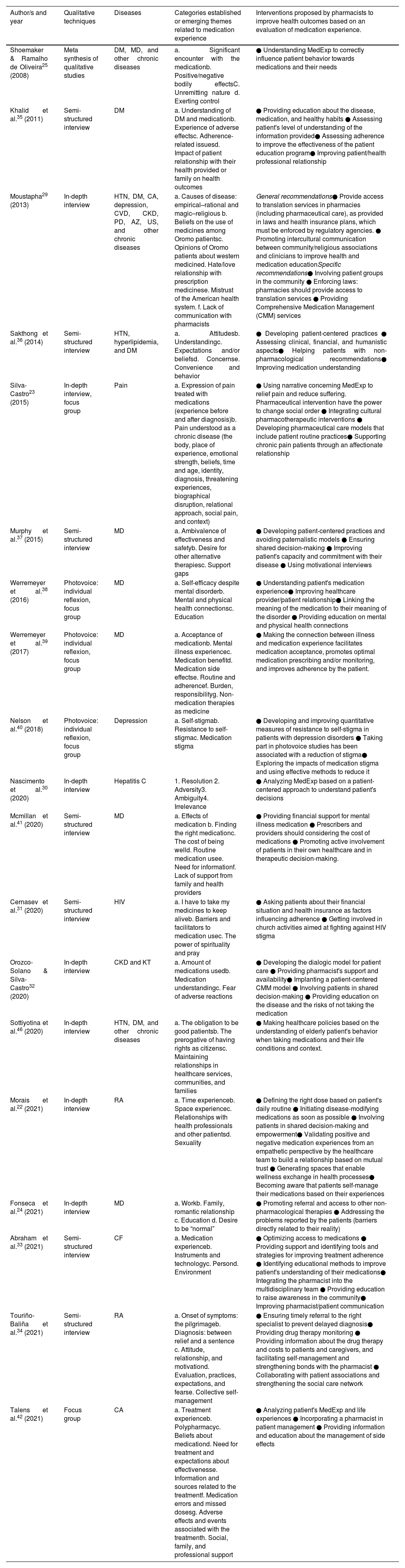

Analysis of contentsThe thematic category «transit of patients with their medications» was established in studies on chronic diseases25,29; mental illness39;41; rheumatoid arthritis22;34; cancer42; and pain23; in USA25;29; Spain23;34;42; Australia41; and Brazil.22 Whereas the «experience of side effects» was the main theme of studies on chronic diseases25;29;35;36; pain23; mental illnesses37;39;40;41; hepatitis C30; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)31; chronic kidney disease (CKD)32; cystic fibrosis33; rheumatoid arthritis34; and cancer42; conducted in USA25;29;31;33;39;40; Thailand36; Spain23;34;42; Canada37; Australia41; Brazil30; and Costa Rica.32 Family support was relevant in the discourse of patients with pain23; mental illness37;41; rheumatoid arthritis34; cancer42; and diabetes mellitus35; in Spain23;34;42; Canada37; Australia41; and Malaysia.35 The relevance of the relationship with healthcare professionals was the theme of studies on chronic diseases29;35;46; mental illnesses37;41; pain23; rheumatoid arthritis22;34; cystic fibrosis33; and cancer42; in Malaysia35; USA29;33; Canada37; Australia41; Thailand46; Spain23;34;42; and Brazil.22;34 The use of alternative therapies was suggested by patients with pain23; chronic29 and mental diseases37;39 in USA29;39; Spain23; and Canada.37 Socioeconomic factors were mentioned by patients with diabetes mellitus35; cystic fibrosis33; mental illnesses41; HIV31; and rheumatoid arthritis34 living in Malaysia35; USA31;33; Australia41; and Spain34.

How is MedExp built from comprehensive medication management, a patient-centered practice?Pharmacists generated MedExp categories from the individual experience of patients who received CMM services. In the earliest study included25, 4 categories were established: significant encounter, bodily effects, unremitting nature, and exerting control over medications. Later studies22,23,29,34,39,41,42 consider MedExp as a dynamic chronological process, by which patients start to notice the benefits of medication but may progressively experience its side effects.23,25,29,30–37,39–42 Patients transition from welfare into fear, which normalizes over the time, when the patient assumes his or her illness and chronic medication.

Pharmacists realized that patients started using and took medications regularly not only for biomedical reasons related to their disease, but also to empirical–rational causes, magical–religious beliefs,29 difficulties at work,24 problems with their partner,24 and the desire to be “normal”.24 Nascimiento et al.30 used the phenomenological framework11,47 and categorized MedExp into: (a) resolution; (b) adversity, as they experience side effects, but also as a representation of the disease; (c) ambiguity, as they do not want to use them, but acknowledge that they need them; and (d) irrelevance, asymptomatic people without drug-related problems.

Other studies adopt a more culturalist and socioeconomic approach and assess the impact of taking medication on their family relationships.23,34,35,37,41,42 This way, MedEx was assessed from a relational perspective.23 These studies reveal support gaps37 and explore how taking medication affects their relationships with others, their sexuality,22 romantic relationships, freedom to make decisions about their medications and what self-care involves in their community.34 These studies integrate patient/pharmacist/healthcare professional relationship as a category influencing MedExp and patient's behavior towards their medications.22,23,29,33,34,35,37,41,42,46 When a therapeutic relationship is established, pharmacists often notice that patients prefer other alternative/complementary therapies.23,29,37,39 Thus, they are aware that patients ask physicians to allow them use treatments from other healthcare models, such as the traditional medicine of their country of origin,29 holistic therapies,37 and medicinal herbs,23 which they consider more healthy and associated with fewer side effects than drug therapies.

Regarding the impact of factors related to the healthcare system, some patients reported mistrust of the healthcare they received.29 In a study,46 older adults had access to medicines through 2 welfare systems. Other authors34 describe MedExp as a pilgrimage across different healthcare services before the adequate treatment is found.

MedExp in the transformation of becoming illThis review reveals that disease experience may change by understanding MedExp. Hence, pain and suffering may improve when patients realize how they understand medication, become aware of their experience with medication22,23,29,34,38–40 and explain their MedExp to the healthcare professional.23 Understanding MedExp, including both positive and negative experiences, facilitates self-care,22 and enables the pharmacist and the patient to reevaluate daily routine in medication regimens.22 Nelson et al.40 proposed reducing self-stigma and self-blame in depression to positively influence the social functioning of a patient. In contrast, if a patient is not aware or conscious about his/her disease they may question the need for taking the medication, as observed by Morais et al.22 and Moustapha.29

Association between socioeconomic status and MedExpKhalid et al.35 included the cost of medication as a MedExp category, since they consider it influences patient decision-making, according to the sociosanitary context. Abraham et al.33 identify collecting medications from different pharmacies as a barrier. McMillan et al.41, Cernasev et al.31, and Touriño-Baliña et al.34 found that MedExp is influenced by the cost of medication, the financial situation of patients, and access to health insurance, of which pharmacist should be cognizant.

Integration of patient beliefs in MedExpSix studies23,25,29–31,35 describe how religion determines MedEXp. According to patient narratives, patients take their mediations with faith,23 the effects of medication reveal as the experience of a magic elixir,25 and religion helps them endure disease and medications.31 Taking medications represents health, but also discomfort when they cause side effects. However, 2 studies29,35uncovered that it is essential that pharmacists are aware of patient beliefs and religion and how they influence MedExp. Interestingly, Mousthapa29 provides the perspective of the Oromo migrants living in USA. The author explains how Oromo beliefs and medicine practices in Ethiopia are in conflict with western biomedical practices. Khalid et al.35 highlight the influence of religion when taking medications during periods of religious significance. The authors identified a significant narrative, since a patient accepts that their health provider reduces insulin dose in periods of fasting during Ramadan. As a result, other patients may make dose adjustments during this religious period, based on their beliefs and without prior consultation. Talens et al.42 categorized beliefs in relation to treatment effectiveness instead of symbolic or religious aspects.

Pharmaceutical interventions proposed after assessing MedExpFollowing MedExp evaluation, pharmacists proposed interventions when providing CMM services (Table 2). The analysis of narratives (Table 3) enabled pharmacists to identify drug-related needs,25,38,39 drug therapy problems, develop care plans,33,38,39,42 and develop contextualized patient education programs,29 by adapting to the financial situation of patients.31 These interventions were aimed at ensuring that medications were correctly indicated, effective, and safe, thereby improving treatment adherence.35 Other studies also explored the association between self-care34 and interaction with their community.22,23,29,31,33,34,40,42,46 Experiences have also been reported of patients who received CMM based on a prior evaluation of MedExp. Thus, pharmacists designed effective interventions that were not only based on biomedical considerations, but also on emotional and social factors, which was effective in improving health outcomes.

Summary of the reviewed studies on medication experience and interventions involving a pharmacist.

| Author/s and year | Qualitative techniques | Diseases | Categories established or emerging themes related to medication experience | Interventions proposed by pharmacists to improve health outcomes based on an evaluation of medication experience. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoemaker & Ramalho de Oliveira25 (2008) | Meta synthesis of qualitative studies | DM, MD, and other chronic diseases | a. Significant encounter with the medicationb. Positive/negative bodily effectsC. Unremitting nature d. Exerting control | ● Understanding MedExp to correctly influence patient behavior towards medications and their needs |

| Khalid et al.35 (2011) | Semi-structured interview | DM | a. Understanding of DM and medicationb. Experience of adverse effectsc. Adherence-related issuesd. Impact of patient relationship with their health provided or family on health outcomes | ● Providing education about the disease, medication, and healthy habits ● Assessing patient's level of understanding of the information provided● Assessing adherence to improve the effectiveness of the patient education program● Improving patient/health professional relationship |

| Moustapha29 (2013) | In-depth interview | HTN, DM, CA, depression, CVD, CKD, PD, AZ, US, and other chronic diseases | a. Causes of disease: empirical–rational and magic–religious b. Beliefs on the use of medicines among Oromo patientsc. Opinions of Oromo patients about western medicined. Hate/love relationship with prescription medicinese. Mistrust of the American health system. f. Lack of communication with pharmacists | General recommendations● Provide access to translation services in pharmacies (including pharmaceutical care), as provided in laws and health insurance plans, which must be enforced by regulatory agencies. ● Promoting intercultural communication between community/religious associations and clinicians to improve health and medication educationSpecific recommendations● Involving patient groups in the community ● Enforcing laws: pharmacies should provide access to translation services ● Providing Comprehensive Medication Management (CMM) services |

| Sakthong et al.36 (2014) | Semi-structured interview | HTN, hyperlipidemia, and DM | a. Attitudesb. Understandingc. Expectations and/or beliefsd. Concernse. Convenience and behavior | ● Developing patient-centered practices ● Assessing clinical, financial, and humanistic aspects● Helping patients with non-pharmacological recommendations● Improving medication understanding |

| Silva-Castro23 (2015) | In-depth interview, focus group | Pain | a. Expression of pain treated with medications (experience before and after diagnosis)b. Pain understood as a chronic disease (the body, place of experience, emotional strength, beliefs, time and age, identity, diagnosis, threatening experiences, biographical disruption, relational approach, social pain, and context) | ● Using narrative concerning MedExp to relief pain and reduce suffering. Pharmaceutical intervention have the power to change social order ● Integrating cultural pharmacotherapeutic interventions ● Developing pharmaceutical care models that include patient routine practices● Supporting chronic pain patients through an affectionate relationship |

| Murphy et al.37 (2015) | Semi-structured interview | MD | a. Ambivalence of effectiveness and safetyb. Desire for other alternative therapiesc. Support gaps | ● Developing patient-centered practices and avoiding paternalistic models ● Ensuring shared decision-making ● Improving patient's capacity and commitment with their disease ● Using motivational interviews |

| Werremeyer et al.38 (2016) | Photovoice: individual reflexion, focus group | MD | a. Self-efficacy despite mental disorderb. Mental and physical health connectionsc. Education | ● Understanding patient's medication experience● Improving healthcare provider/patient relationship● Linking the meaning of the medication to their meaning of the disorder ● Providing education on mental and physical health connections |

| Werremeyer et al.39 (2017) | Photovoice: individual reflexion, focus group | MD | a. Acceptance of medicationb. Mental illness experiencec. Medication benefitd. Medication side effectse. Routine and adherencef. Burden, responsibilityg. Non-medication therapies as medicine | ● Making the connection between illness and medication experience facilitates medication acceptance, promotes optimal medication prescribing and/or monitoring, and improves adherence by the patient. |

| Nelson et al.40 (2018) | Photovoice: individual reflexion, focus group | Depression | a. Self-stigmab. Resistance to self-stigmac. Medication stigma | ● Developing and improving quantitative measures of resistance to self-stigma in patients with depression disorders ● Taking part in photovoice studies has been associated with a reduction of stigma● Exploring the impacts of medication stigma and using effective methods to reduce it |

| Nascimento et al.30 (2020) | In-depth interview | Hepatitis C | 1. Resolution 2. Adversity3. Ambiguity4. Irrelevance | ● Analyzing MedExp based on a patient-centered approach to understand patient's decisions |

| Mcmillan et al.41 (2020) | Semi-structured interview | MD | a. Effects of medication b. Finding the right medicationc. The cost of being welld. Routine medication usee. Need for informationf. Lack of support from family and health providers | ● Providing financial support for mental illness medication ● Prescribers and providers should considering the cost of medications ● Promoting active involvement of patients in their own healthcare and in therapeutic decision-making. |

| Cernasev et al.31 (2020) | Semi-structured interview | HIV | a. I have to take my medicines to keep aliveb. Barriers and facilitators to medication usec. The power of spirituality and pray | ● Asking patients about their financial situation and health insurance as factors influencing adherence ● Getting involved in church activities aimed at fighting against HIV stigma |

| Orozco-Solano & Silva-Castro32 (2020) | In-depth interview | CKD and KT | a. Amount of medications usedb. Medication understandingc. Fear of adverse reactions | ● Developing the dialogic model for patient care ● Providing pharmacist's support and availability● Implanting a patient-centered CMM model ● Involving patients in shared decision-making ● Providing education on the disease and the risks of not taking the medication |

| Sottiyotina et al.46 (2020) | In-depth interview | HTN, DM, and other chronic diseases | a. The obligation to be good patientsb. The prerogative of having rights as citizensc. Maintaining relationships in healthcare services, communities, and families | ● Making healthcare policies based on the understanding of elderly patient's behavior when taking medications and their life conditions and context. |

| Morais et al.22 (2021) | In-depth interview | RA | a. Time experienceb. Space experiencec. Relationships with health professionals and other patientsd. Sexuality | ● Defining the right dose based on patient's daily routine ● Initiating disease-modifying medications as soon as possible ● Involving patients in shared decision-making and empowerment● Validating positive and negative medication experiences from an empathetic perspective by the healthcare team to build a relationship based on mutual trust ● Generating spaces that enable wellness exchange in health processes● Becoming aware that patients self-manage their medications based on their experiences |

| Fonseca et al.24 (2021) | In-depth interview | MD | a. Workb. Family, romantic relationship c. Education d. Desire to be “normal” | ● Promoting referral and access to other non-pharmacological therapies ● Addressing the problems reported by the patients (barriers directly related to their reality) |

| Abraham et al.33 (2021) | Semi-structured interview | CF | a. Medication experienceb. Instruments and technologyc. Persond. Environment | ● Optimizing access to medications ● Providing support and identifying tools and strategies for improving treatment adherence ● Identifying educational methods to improve patient's understanding of their medications● Integrating the pharmacist into the multidisciplinary team ● Providing education to raise awareness in the community● Improving pharmacist/patient communication |

| Touriño-Baliña et al.34 (2021) | Semi-structured interview | RA | a. Onset of symptoms: the pilgrimageb. Diagnosis: between relief and a sentence c. Attitude, relationship, and motivationd. Evaluation, practices, expectations, and fearse. Collective self-management | ● Ensuring timely referral to the right specialist to prevent delayed diagnosis● Providing drug therapy monitoring ● Providing information about the drug therapy and costs to patients and caregivers, and facilitating self-management and strengthening bonds with the pharmacist ● Collaborating with patient associations and strengthening the social care network |

| Talens et al.42 (2021) | Focus group | CA | a. Treatment experienceb. Polypharmacyc. Beliefs about medicationd. Need for treatment and expectations about effectivenesse. Information and sources related to the treatmentf. Medication errors and missed dosesg. Adverse effects and events associated with the treatmenth. Social, family, and professional support | ● Analyzing patient's MedExp and life experiences ● Incorporating a pharmacist in patient management ● Providing information and education about the management of side effects |

RA: rheumatoid arthritis; AZ: Alzheimer's disease CA: cancer; DM: diabetes mellitus; CVD: cardiovascular disease; MI: mental disorders; PD: pulmonary disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CF: cystic fibrosis; HTN: arterial hypertension; US: upset stomach; KT: kidney transplantation; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

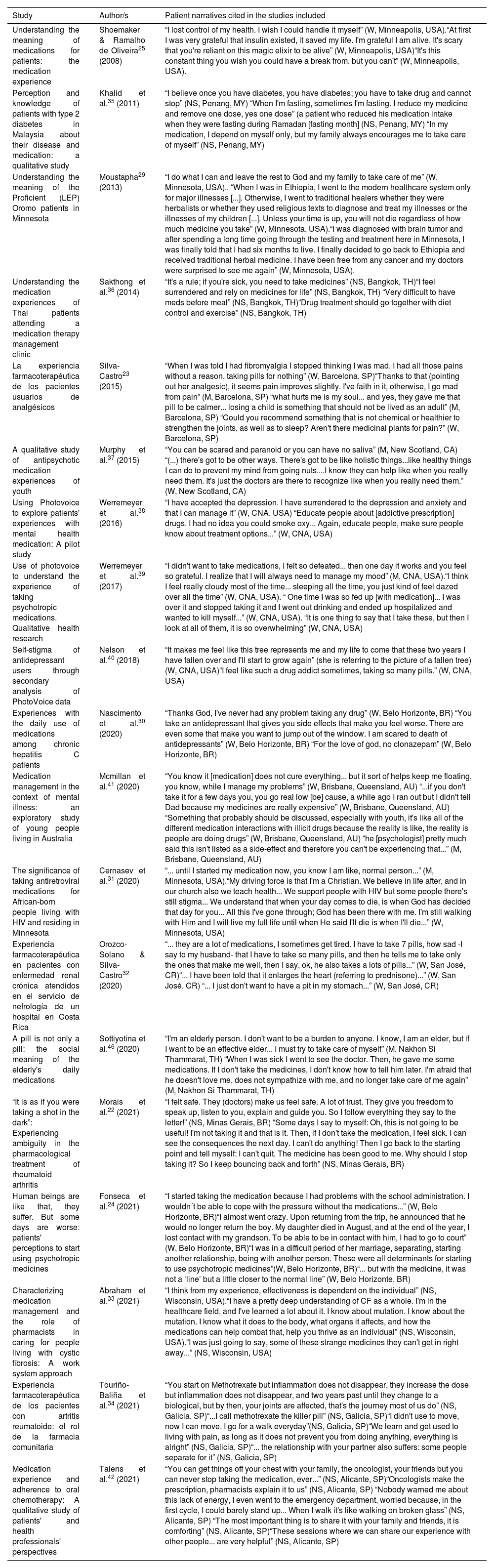

Patient narratives considered for the development of pharmaceutical interventions.

| Study | Author/s | Patient narratives cited in the studies included |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding the meaning of medications for patients: the medication experience | Shoemaker & Ramalho de Oliveira25 (2008) | “I lost control of my health. I wish I could handle it myself” (W, Minneapolis, USA).“At first I was very grateful that insulin existed, it saved my life. I'm grateful I am alive. It's scary that you're reliant on this magic elixir to be alive” (W, Minneapolis, USA)“It's this constant thing you wish you could have a break from, but you can't” (W, Minneapolis, USA). |

| Perception and knowledge of patients with type 2 diabetes in Malaysia about their disease and medication: a qualitative study | Khalid et al.35 (2011) | “I believe once you have diabetes, you have diabetes; you have to take drug and cannot stop” (NS, Penang, MY) “When I'm fasting, sometimes I'm fasting. I reduce my medicine and remove one dose, yes one dose” (a patient who reduced his medication intake when they were fasting during Ramadan [fasting month] (NS, Penang, MY) “In my medication, I depend on myself only, but my family always encourages me to take care of myself” (NS, Penang, MY) |

| Understanding the meaning of the Proficient (LEP) Oromo patients in Minnesota | Moustapha29 (2013) | “I do what I can and leave the rest to God and my family to take care of me” (W, Minnesota, USA).. “When I was in Ethiopia, I went to the modern healthcare system only for major illnesses [...]. Otherwise, I went to traditional healers whether they were herbalists or whether they used religious texts to diagnose and treat my illnesses or the illnesses of my children [...]. Unless your time is up, you will not die regardless of how much medicine you take” (W, Minnesota, USA).“I was diagnosed with brain tumor and after spending a long time going through the testing and treatment here in Minnesota, I was finally told that I had six months to live. I finally decided to go back to Ethiopia and received traditional herbal medicine. I have been free from any cancer and my doctors were surprised to see me again” (W, Minnesota, USA). |

| Understanding the medication experiences of Thai patients attending a medication therapy management clinic | Sakthong et al.36 (2014) | “It's a rule; if you're sick, you need to take medicines” (NS, Bangkok, TH)“I feel surrendered and rely on medicines for life” (NS, Bangkok, TH) “Very difficult to have meds before meal” (NS, Bangkok, TH)“Drug treatment should go together with diet control and exercise” (NS, Bangkok, TH) |

| La experiencia farmacoterapéutica de los pacientes usuarios de analgésicos | Silva-Castro23 (2015) | “When I was told I had fibromyalgia I stopped thinking I was mad. I had all those pains without a reason, taking pills for nothing” (W, Barcelona, SP)“Thanks to that (pointing out her analgesic), it seems pain improves slightly. I've faith in it, otherwise, I go mad from pain” (M, Barcelona, SP) “what hurts me is my soul... and yes, they gave me that pill to be calmer... losing a child is something that should not be lived as an adult” (M, Barcelona, SP) “Could you recommend something that is not chemical or healthier to strengthen the joints, as well as to sleep? Aren't there medicinal plants for pain?” (W, Barcelona, SP) |

| A qualitative study of antipsychotic medication experiences of youth | Murphy et al.37 (2015) | “You can be scared and paranoid or you can have no saliva” (M, New Scotland, CA) “(...) there's got to be other ways. There's got to be like holistic things...like healthy things I can do to prevent my mind from going nuts....I know they can help like when you really need them. It's just the doctors are there to recognize like when you really need them.” (W, New Scotland, CA) |

| Using Photovoice to explore patients' experiences with mental health medication: A pilot study | Werremeyer et al.38 (2016) | “I have accepted the depression. I have surrendered to the depression and anxiety and that I can manage it” (W, CNA, USA) “Educate people about [addictive prescription] drugs. I had no idea you could smoke oxy... Again, educate people, make sure people know about treatment options...” (W, CNA, USA) |

| Use of photovoice to understand the experience of taking psychotropic medications. Qualitative health research | Werremeyer et al.39 (2017) | “I didn't want to take medications, I felt so defeated... then one day it works and you feel so grateful. I realize that I will always need to manage my mood” (M, CNA, USA).“I think I feel really cloudy most of the time... sleeping all the time, you just kind of feel dazed over all the time” (W, CNA, USA). “ One time I was so fed up [with medication]... I was over it and stopped taking it and I went out drinking and ended up hospitalized and wanted to kill myself...” (W, CNA, USA). “It is one thing to say that I take these, but then I look at all of them, it is so overwhelming” (W, CNA, USA) |

| Self-stigma of antidepressant users through secondary analysis of PhotoVoice data | Nelson et al.40 (2018) | “It makes me feel like this tree represents me and my life to come that these two years I have fallen over and I'll start to grow again” (she is referring to the picture of a fallen tree) (W, CNA, USA)“I feel like such a drug addict sometimes, taking so many pills.” (W, CNA, USA) |

| Experiences with the daily use of medications among chronic hepatitis C patients | Nascimento et al.30 (2020) | “Thanks God, I've never had any problem taking any drug” (W, Belo Horizonte, BR) “You take an antidepressant that gives you side effects that make you feel worse. There are even some that make you want to jump out of the window. I am scared to death of antidepressants” (W, Belo Horizonte, BR) “For the love of god, no clonazepam” (W, Belo Horizonte, BR) |

| Medication management in the context of mental illness: an exploratory study of young people living in Australia | Mcmillan et al.41 (2020) | “You know it [medication] does not cure everything... but it sort of helps keep me floating, you know, while I manage my problems” (W, Brisbane, Queensland, AU) “...if you don't take it for a few days you, you go real low [be] cause, a while ago I ran out but I didn't tell Dad because my medicines are really expensive” (W, Brisbane, Queensland, AU) “Something that probably should be discussed, especially with youth, it's like all of the different medication interactions with illicit drugs because the reality is like, the reality is people are doing drugs” (W, Brisbane, Queensland, AU) “he [psychologist] pretty much said this isn't listed as a side-effect and therefore you can't be experiencing that...” (M, Brisbane, Queensland, AU) |

| The significance of taking antiretroviral medications for African-born people living with HIV and residing in Minnesota | Cernasev et al.31 (2020) | “... until I started my medication now, you know I am like, normal person...” (M, Minnesota, USA).“My driving force is that I'm a Christian. We believe in life after, and in our church also we teach health... We support people with HIV but some people there's still stigma... We understand that when your day comes to die, is when God has decided that day for you... All this I've gone through; God has been there with me. I'm still walking with Him and I will live my full life until when He said I'll die is when I'll die...” (W, Minnesota, USA) |

| Experiencia farmacoterapéutica en pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica atendidos en el servicio de nefrología de un hospital en Costa Rica | Orozco-Solano & Silva-Castro32 (2020) | “... they are a lot of medications, I sometimes get tired. I have to take 7 pills, how sad -I say to my husband- that I have to take so many pills, and then he tells me to take only the ones that make me well, then I say, ok, he also takes a lots of pills...” (W, San José, CR)“... I have been told that it enlarges the heart (referring to prednisone)...” (W, San José, CR) “... I just don't want to have a pit in my stomach...” (W, San José, CR) |

| A pill is not only a pill: the social meaning of the elderly's daily medications | Sottiyotina et al.46 (2020) | “I'm an elderly person. I don't want to be a burden to anyone. I know, I am an elder, but if I want to be an effective elder... I must try to take care of myself” (M, Nakhon Si Thammarat, TH) “When I was sick I went to see the doctor. Then, he gave me some medications. If I don't take the medicines, I don't know how to tell him later. I'm afraid that he doesn't love me, does not sympathize with me, and no longer take care of me again” (M, Nakhon Si Thammarat, TH) |

| “It is as if you were taking a shot in the dark”: Experiencing ambiguity in the pharmacological treatment of rheumatoid arthritis | Morais et al.22 (2021) | “I felt safe. They (doctors) make us feel safe. A lot of trust. They give you freedom to speak up, listen to you, explain and guide you. So I follow everything they say to the letter!” (NS, Minas Gerais, BR) “Some days I say to myself: Oh, this is not going to be useful! I'm not taking it and that is it. Then, if I don't take the medication, I feel sick. I can see the consequences the next day. I can't do anything! Then I go back to the starting point and tell myself: I can't quit. The medicine has been good to me. Why should I stop taking it? So I keep bouncing back and forth” (NS, Minas Gerais, BR) |

| Human beings are like that, they suffer. But some days are worse: patients' perceptions to start using psychotropic medicines | Fonseca et al.24 (2021) | “I started taking the medication because I had problems with the school administration. I wouldn´t be able to cope with the pressure without the medications...” (W, Belo Horizonte, BR)“I almost went crazy. Upon returning from the trip, he announced that he would no longer return the boy. My daughter died in August, and at the end of the year, I lost contact with my grandson. To be able to be in contact with him, I had to go to court” (W, Belo Horizonte, BR)“I was in a difficult period of her marriage, separating, starting another relationship, being with another person. These were all determinants for starting to use psychotropic medicines”(W, Belo Horizonte, BR)“... but with the medicine, it was not a ‘line’ but a little closer to the normal line” (W, Belo Horizonte, BR) |

| Characterizing medication management and the role of pharmacists in caring for people living with cystic fibrosis: A work system approach | Abraham et al.33 (2021) | “I think from my experience, effectiveness is dependent on the individual” (NS, Wisconsin, USA).“I have a pretty deep understanding of CF as a whole. I'm in the healthcare field, and I've learned a lot about it. I know about mutation. I know about the mutation. I know what it does to the body, what organs it affects, and how the medications can help combat that, help you thrive as an individual” (NS, Wisconsin, USA).“I was just going to say, some of these strange medicines they can't get in right away...” (NS, Wisconsin, USA) |

| Experiencia farmacoterapéutica de los pacientes con artritis reumatoide: el rol de la farmacia comunitaria | Touriño-Baliña et al.34 (2021) | “You start on Methotrexate but inflammation does not disappear, they increase the dose but inflammation does not disappear, and two years past until they change to a biological, but by then, your joints are affected, that's the journey most of us do” (NS, Galicia, SP)“...I call methotrexate the killer pill” (NS, Galicia, SP)“I didn't use to move, now I can move. I go for a walk everyday”(NS, Galicia, SP)“We learn and get used to living with pain, as long as it does not prevent you from doing anything, everything is alright” (NS, Galicia, SP)“... the relationship with your partner also suffers: some people separate for it” (NS, Galicia, SP) |

| Medication experience and adherence to oral chemotherapy: A qualitative study of patients' and health professionals' perspectives | Talens et al.42 (2021) | “You can get things off your chest with your family, the oncologist, your friends but you can never stop taking the medication, ever...” (NS, Alicante, SP)“Oncologists make the prescription, pharmacists explain it to us” (NS, Alicante, SP) “Nobody warned me about this lack of energy, I even went to the emergency department, worried because, in the first cycle, I could barely stand up... When I walk it's like walking on broken glass” (NS, Alicante, SP) “The most important thing is to share it with your family and friends, it is comforting” (NS, Alicante, SP)“These sessions where we can share our experience with other people... are very helpful” (NS, Alicante, SP) |

Narratives from studies published in Spanish were translated into English by a professional translation to enable comparative analysis. Additionally, narratives are identified with the gender reported by the authors and research site. W: woman, M: man, NS: not available in the original study. AU: Australia; BR: Brazil; CA: Canada; CR: Costa Rica; SP: Spain; MY: Malaysia; TH: Thailand; USA: United States; CNA: city not available.

Nine studies29,32–36,38,41,42 revealed the impact of contextualized patient education and information interventions on medication and disease.29 By integrating MedExp into pharmaceutical care programs, pharmacists propose to educate and provide information about the appropriate use,38 therapeutic use, and cost34,41 of medications. In their programs, pharmacists explained potential adverse effects42 to prevent fear and mistrust of medications, 36 and improve adherence.42 These interventions were focused on understanding complications32,35,38 of mental illness38; diabetes mellitus35; CKD32; and cystic fibrosis33, and incorporated healthy habits, once they had verified that the patient had understood the information provided and adherence had been assessed again.35 Authors highlight the relevance of adapting information to the age of the patient.41 From a collective perspective, authors propose getting involved in intercultural community education by collaborating with different associations.33,34

Cultural pharmacotherapeutic interventions, support networks, healthcare policiesNine studies22,23,29,31,33,34,40,42,46 recommend seeking support from the family, community, and patient associations to reduce cultural barriers and improve health outcomes. By adopting a collective and contextualized perspective,23 pharmacists suggest to implement pharmacotherapeutic interventions that involve intercultural communication,29 based on friends,42 relatives,33,42 religion,31 and community34 networks. In photovoice studies,38,39,40 pair interaction created a space for sharing experiences, which improved welfare22 and helped break stigmas.31,40 Regarding healthcare policies, Moustapha29 proposed that public healthcare agencies provide funds to overcome language barriers in contextualized interventions. Sottiyotin et al.46 recommend that healthcare policies are developed to improve quality of life and medication use, according to the life context and cultural practices of the older adult.

Characteristics of the interventions suggestedThe dialogic model, symmetric therapeutic relationships, and shared decision-making were identified as indicators of the quality of interventions in patients with pain,23 CKD,32 mental illnesses,37,41 rheumatoid arthritis,22,34 diabetes mellitus,35 and cystic fibrosis,33 in studies conducted in Spain,23,34 Costa Rica,32 USA,33 Malaysia,35 Brazil,22 Australia,41 and Canada.37 The adoption of an integral approach and referral to other professionals were recommended in patients with chronic diseases36; pain23; cystic fibrosis33; mental illness24; and rheumatoid arthritis,34 in Spain,23,34 USA,33 Brazil,24 and Thailand.36

Dialogic model, symmetric therapeutic relationship and shared decision-makingEight studies22,23,32–35,37,41recommended integrating at least one of the following characteristics in interventions. Promoting the dialogic model23,32 and establishing symmetrical relationships based on empathy, affectiveness, solidarity, and respect for patients will help the pharmacist meet the drug-related needs of patients, thereby leaving the commercial transaction as secondary.23 When the pharmacist–patient relationship improves, the pharmacist becomes more approachable,22,23,32–35 which creates a climate of trust32 where patients and caregivers become aware of their decisions about medications. A good pharmacist–patient relationship favors shared decision-making,22,37,41 medication understanding, motivation,37 and patient empowerment.22

Integral approach and referral to other health professionalsFive studies23,24,33,34,36 highlight that understanding MedExp makes it possible to translate the integral approach into clinical practice and involve other health professionals. This way, the pharmacist provides CMM on the basis of their understanding of the physiological, social (work, relationship),24 and political concerns of the patient, as they consider healthcare pluralism,48 thereby incorporating sociocultural factors into clinical practice.23 By adopting a contextualized approach and on request of the patient, the pharmacist provides advice on the complementary and alternative therapies available36 and refers the patient to the physician in a timely manner to ensure early diagnosis.34

DiscussionThis scoping review improves our understanding of how the idea of MedExp has evolved, as a key concept for pharmacists. The information obtained is useful, given the heterogeneity and complexity of the studies retrieved, selected, and analyzed. PRISMA guidelines were a valuable instrument20 in managing the heterogeneous categorization of MedExp and different types of pharmaceutical interventions implemented. In addition, PRISMA guidelines49 helped us to map the qualitative research techniques used and the results obtained on this broad emergent theme. To such purpose, pharmacists need to use qualitative health research methods that had not been used before in this field.

A limitation of this study is that studies published in languages other than English and Spanish were excluded, which prevented the analysis of MedExp in other sociocultural contexts. Although search was carried out on 4 databases, it may have been inaccurate, given that specific MeSH terms have not yet been established. Thus, the lack of standard keywords may have hindered retrieval of relevant articles due to indexation problems.

Another relevant aspect when performing a scoping review of qualitative research studies is that the aim was to understand what happens in the life of patients taking medications and their context. For this reason, it would have been useful to include qualitative studies that analyzed the progress of MedExp following the implementation of pharmaceutical interventions. When pharmacists get an insight into the symbolic world of the patient and decodify the meaning of medication users, they are able to understand, interpret50and analyze significant events6 to help patients change their medication experience. Access to this world is gained using qualitative research methods. Therefore, future studies should be focused on social practices to analyze what patients actually do and assess relationships between the stakeholders51 involved in patient care.

Regarding the quality of studies, some studies do not describe the research paradigm or theoretical frameworks used. This limitation hinders comparative analysis of contents, since the theoretical rationale for the qualitative analysis performed is not available. As a result of the influence of the biomedical model on CMM, sociocultural problems are not addressed. However, these factors, such as those that would emerge if cross-sectional or gender-based approaches were adopted, are most frequently included in biomedical research. This way, the exclusion from analysis of social determining factors or race-, gender-, or religion-based discrimination, along with other social phenomena affecting medication users, would not be reproduced.

Regarding the analysis of contents, Shoemaker et al.25 laid the foundations for the categorization of MedExp from a phenomenological perspective.22,24,25,30 Hence, categories are based on patient's perceived sensory experience and on the direct relationship between sensory perceptions and learning how to use medicines from the body scheme of each patient.11 This theory is related to the concept of embodiment.47,52 According to Esteban,44 this concept does not only refer to the biological body, but also understands the body as a “conscious, experiential, acting and interpreting entity”.

Other authors23,29,31,34,35,37,41,42,46 categorize MedExp from a social-constructivist53,54 and symbolic interactionism approach.55,56 From these sociological perspectives, the authors explore how patients build and implement what they understand about their medication in socially mediated contexts. Also, these studies reveal that ignoring that social life is built from interactions with others invalidate the individual meaning4,6 assigned to any experience that is interpreted from an individual rather than collective perspective. According to these analytical perspectives,57 experience is a human construct and patient actively takes part in this transformative process. From the social-constructivist and interaction perspective, MedExp cannot be separated from the social processes that compose it or from the context where it develops and evolves. The studies23,29,34,39,41,42 are based on this analytical perspective. Thus, they categorize MedExp as a journey, a dynamic process resulting from interaction with the environment, with special relevance given to the interrelation between MedExp and chronicity.58

The studies that use illness narrative59,60 on how patients use their medications to analyze MedExp focus discourses on individuality. However, although these studies are relevant, they may miss the information provided in the narratives of other stakeholders that interact with the patient, which will determine “the building of MedExp”, with the latter having a collective nature.61

Understanding and contextualizing MedExp may transform illness experience.22,23,29,34,38–40 Psychologists and specialists in social psychology affirm that listening to and reconstructing their own history62 is therapeutical for patients and creates a climate of empathy and trust.60 Some studies have assessed the influence of emotions.63 Thus, MedExp is determined by the psychological characteristics of medicine users, thereby conditioning self-perception of the worsening or improvement of their health.64,65 Good6 defines that the generation of narratives as an individual and social process that may help understand the impact of illness and medication on the life of the patient, and prevent its disappearance or deconstruction. According to the author, “narratives do not only describe the source of suffering, but also help understand its location and origin and find a solution”. Some pharmacists focus their interventions on the discourse of the patient and provide realistic solutions through contextualized pharmaceutical interventions. The studies included confirm the hypothesis of Menéndez66 that despite the high understanding of medication by patients, their personal experience often moves them to quit or use their medications differently to as prescribed. Some health professional could label their patients as “non-adherent” based on a value judgment that ignores the sociocultural determining factors that mediate that decision. However, as uncovered in studies,22,23,29,34,38–40 when a pharmacist takes the time to analyze patient's experience in more detail, they understand the cause and may provide a solution. By understanding MedExp, pharmacists learn about patient's reasons for non-adherence and identify the individual needs or barriers experienced by patients with a particular condition. The attempt to quantify adherence is based on the rationale of the prevailing biomedical model,66,67 which invalidates beliefs and reduces the psychosocial context of a patient to a numerical parameter. In this line, Martínez-Granados68 explain that pharmacists should consider whether they look at the other (the patient) from a position of equal power and mutual respect, where the patient is no imposed to obey an order, or from a perspective based on the understanding of the sociocultural meanings that determine their behaviors.

This review confirmed the influence of socioeconomic conditions in personal experiences.31,33–35,41 The World Health Organization69 defines as a fundamental right of every human being the right to health enjoyed without discrimination on the grounds of race, age, ethnicity, or any other factor. The WHO also highlights the need for states to take steps to redress any discriminatory law, practice, or policy. Finally, the organization establishes that the price of the medication and financial situation of each user of pharmacy services should always be considered when designing individual pharmaceutical interventions. Patients occasionally reduce dose or quit medication to save costs or because they are not subsidized by the public health system.

Considering narratives about beliefs, some studies23,25,31 associate discourses with the symbolic world of patients, consistently with Good's approach.6 This point of view dismisses beliefs as statements that others do about what they think (convictions), which transmit a value judgment to the investigator.36,42 The integration of beliefs has demonstrated that people have capacity of self-care, and knowledge bases its legitimacy on religion.66 Accordingly, patients' beliefs have been considered in some pharmaceutical interventions,35,39 including patient education on diseases and medications8 in contextualized healthcare practices where understanding the religious beliefs of patients was key when providing guidance to patients on their medications.35

With respect to education on medications and disease, studies29,32–36,38,41,42 consistently demonstrate that understanding MedExp helped develop individualized8 and collective34 patient education strategies. However, although education strategies may transform MedExp,2 some studies23,29,34,37,39 reveal that patients have a deep understanding of their disease and medication and develop self-care practices.66 On the basis of the evidence available, it would not be useful to undertake an educational campaign without first knowing the needs of the patient, without imposing biomedical knowledge, or excluding or denying discourses (a power relationship), when symmetrical relationships must be fostered.70 Thus, the patient's “clues” or “their presumptive self-diagnosis” should be first understood.66

The cultural interventions analyzed 22,23,29,31,33,34,40,42,46 reveal the advantages of integrating support networks, and involving relatives and community and patient associations to reduce cultural barriers in CMM. These studies confirm in practice what some authors61,71 warn about the fact that patient-centered practices may be insufficient if they do not involve contextualized practices in the community of the person who gets ill. Only this way pharmacists will be able to provide “contextualized care”.61

In the same line of Martínez-Hernáez,67 the reviewed studies22,23,32–35,37,41 suggest interventions that incorporate the dialogic model, symmetrical therapeutic relationships, and shared decision-making. This approach is based on the fact that the dialogic model is a bidirectional, multidimensional flow of information resulting from a reciprocal relationship of balanced interaction. This approach creates a connection between the health professional and the patient, based on the understanding of mutual knowledge, which helps them build together a new experience and serve as a basis for shared decision-making. With respect to building symmetrical therapeutic relationships, several studies23,32 identify trust as a predictive factor of intervention success.72

The interventions involving a comprehensive approach and timely referrals to other health professionals described in the studies23,24,33,34,36 adopt the biopsychosocial model. Thus, they suggest to analyze disease in the context of patient's life on the basis of their activities, feelings, and behaviors, rather than adopting the hegemonic biomedical model, which emphasizes the mind–body binomial.73,74 Pharmacists are aware of healthcare pluralism48 and that they are part of conventional care models. However, they are also surrounded by traditional, alternative, popular models, such as self-care.75 The latter involve relationships between communities/social subjects; therefore, they understand what living with medication actually involves and how people deal with their health problems in their everyday life. Using this approach, they have analyzed the effectiveness of interventions and optimized pharmacotherapy based on actual patient experiences. Therefore, pharmacists have adopted the vision of CMM as an integrative care practice. With this approach, they can determine whether to refer a patient or seek alliances with other health agents for the sake of the well-being of patients. When healthcare practices are considered as social facts, the relational approach66 is adopted, which enables to advance towards contextualized clinical practices.61,71

In the light of the findings of this scoping review, future research should broaden the definition of MedExp as the experience lived by a person who uses their medications according to their individual, psychological, and social qualities. Experience with medications is bodily, intentional, intersubjective, and relational and extend to the collective context, as it involves the beliefs, culture, ethics, and socioeconomic and political reality of each person in their context.

Contribution to the scientific literatureAlthough it is lived individually, medication experience is collective and requires a relational approach for clinical practices to be contextualized.

Implications of the results obtainedUnderstanding medication experience enables the provision of contextualized pharmaceutical interventions, thereby resulting in improved health outcomes.

FundingNone of the authors received additional support from internal or external entities. This scoping review was conducted as part of the PhD program of San Jorge University, therefore, it is the product of a scholar activity. No funding.