To evaluate the impact of an intervention algorithm on penicillin allergy label reassessment in emergency department patients, aiming to optimize antibiotic selection and improve patient safety.

MethodsA retrospective observational study was conducted in a 450-bed hospital, including adult patients with a penicillin allergy label admitted to the emergency department between November 2023 and August 2024. An algorithm developed by the pharmacy service in collaboration with the ASP team was applied, based on validated tools such as the Penicillin Allergy De-Labelling Toolkit, PEN-FAST, and Antibiotic Allergy Assessment Tool. Demographic data, allergy history, and clinical outcomes were collected. The acceptance of recommendations and the incidence of adverse reactions were analyzed.

ResultsA total of 66 patients were evaluated. Delabeling was proposed in 35 (53.03%) patients, skin testing in 13 (19.69%), oral provocation testing in 9 (13.63%), and label maintenance in 9 (13.63%). A total of 89.39% of the recommendations were accepted, achieving effective delabeling in 42 patients. No adverse reactions were recorded. In 21 cases, antibiotic therapy was optimized following the intervention.

ConclusionsThe implementation of a structured algorithm for penicillin allergy reassessment in emergency settings is both effective and safe. Its application facilitates antibiotic optimization, improves patient safety, and reduces broad-spectrum antibiotic use. This study highlights the role of hospital pharmacists in drug allergy management and antimicrobial stewardship.

evaluar el impacto de un algoritmo de intervención en la reevaluación de etiquetas de alergia a penicilinas en pacientes ingresados en urgencias, con el objetivo de optimizar la selección antibiótica y mejorar la seguridad del paciente.

Métodosestudio observacional retrospectivo, realizado en un hospital de 450 camas, incluyendo pacientes adultos con etiqueta de alergia a la penicilina, ingresados en urgencias entre noviembre de 2023 y agosto de 2024. Se aplicó un algoritmo desarrollado por el servicio de farmacia en colaboración con el equipo PROA, basado en herramientas validadas como Penicillin Allergy De-Labelling Toolkit, PEN-FAST y Antibiotic Allergy Assessment Tool. Se recogieron datos demográficos, antecedentes alérgicos y resultados clínicos. Se analizó la aceptación de las recomendaciones y la incidencia de efectos adversos.

Resultadosse evaluaron 66 pacientes. Se propuso el desetiquetado en 35 (53,03%) pacientes, pruebas cutáneas en 13 (19,69%), prueba de provocación oral en 9 (13,63%) y mantenimiento de la etiqueta en 9 (13,63%). El 89,39% de las propuestas fueron aceptadas, logrando el desetiquetado efectivo en 42 pacientes. No se registraron reacciones adversas. En 21 casos, se optimizó la antibioticoterapia tras la intervención.

Conclusionesla implementación de un algoritmo estructurado para la reevaluación de alergias a penicilinas en urgencias es efectiva y segura. Su aplicación facilita la optimización de la antibioticoterapia, mejora la seguridad del paciente y reduce el uso de antibióticos de amplio espectro. Este estudio subraya el papel del farmacéutico hospitalario en la gestión de alergias a medicamentos y en la optimización del tratamiento antimicrobiano.

Infectious processes are among the most common causes of visits to hospital EDs, with antibiotics being one of the most frequently prescribed types of medications in these settings.1,2 It is therefore necessary to increase surveillance of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing to avoid short- and long-term complications for patients. Classifying, or labeling, a patient as allergic to β-lactams, mainly penicillins, is a common practice in hospitals, impacting approximately 10% of the world's population.3 The consequences of incorrectly labeling patients as having a penicillin allergy are significant. These patients receive broader-spectrum antibiotics, which increases their risk of infection from resistant organisms, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile.4–6 They also have higher rates of surgical site infections and adverse effects, as well as healthcare-associated infections. The aforementioned complications can result in longer hospitalisation, which can have a negative impact on patient health and lead to increased healthcare costs.7

It has been determined that the majority of patients who report a penicillin allergy are not actually allergic. In fact, several studies have shown that as many as 95% of patients labeled as penicillin-allergic can tolerate this class of antimicrobial without complication.3,8 In addition, a significant percentage of patients who have experienced a genuine hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin lose this sensitivity over time. It is estimated that 80% of these patients are no longer allergic after 10 years.3,8

This issue can be addressed using clinical decision algorithms and assessment tools. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness and safety of involving hospital pharmacists in assessing and removing penicillin allergy labels. This can be achieved by creating these types of algorithms, conducting clinical interviews, reviewing electronic records, and conducting oral challenge tests and skin allergy tests.9–20 The involvement of hospital pharmacists has facilitated the accurate confirmation or ruling out of penicillin allergies, optimized antibiotic use, reduced the unnecessary prescription of broad-spectrum alternatives, and enhanced patient clinical outcomes.9–20

This retrospective observational study analyzed the impact of using an intervention algorithm to evaluate penicillin allergy labels in patients admitted to the emergency department (ED). The aim of the study was to provide evidence of the effectiveness and safety of this approach in a real hospital setting.

Materials and methodsStudy design, population, and sampleA retrospective observational study was conducted in a 450-bed hospital with approximately 26,000 admissions per year. The study period ran from 1 November 2023 to 31 August 2024. The study population included all adult patients admitted to the ED during the study period. The following inclusion criteria were applied: patients aged over 18 years, with a stay in the ED of more than 16 hours, receiving antibiotic treatment, with a penicillin allergy label, and available for a clinical interview by ED pharmacists during working hours (8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., Monday to Friday).

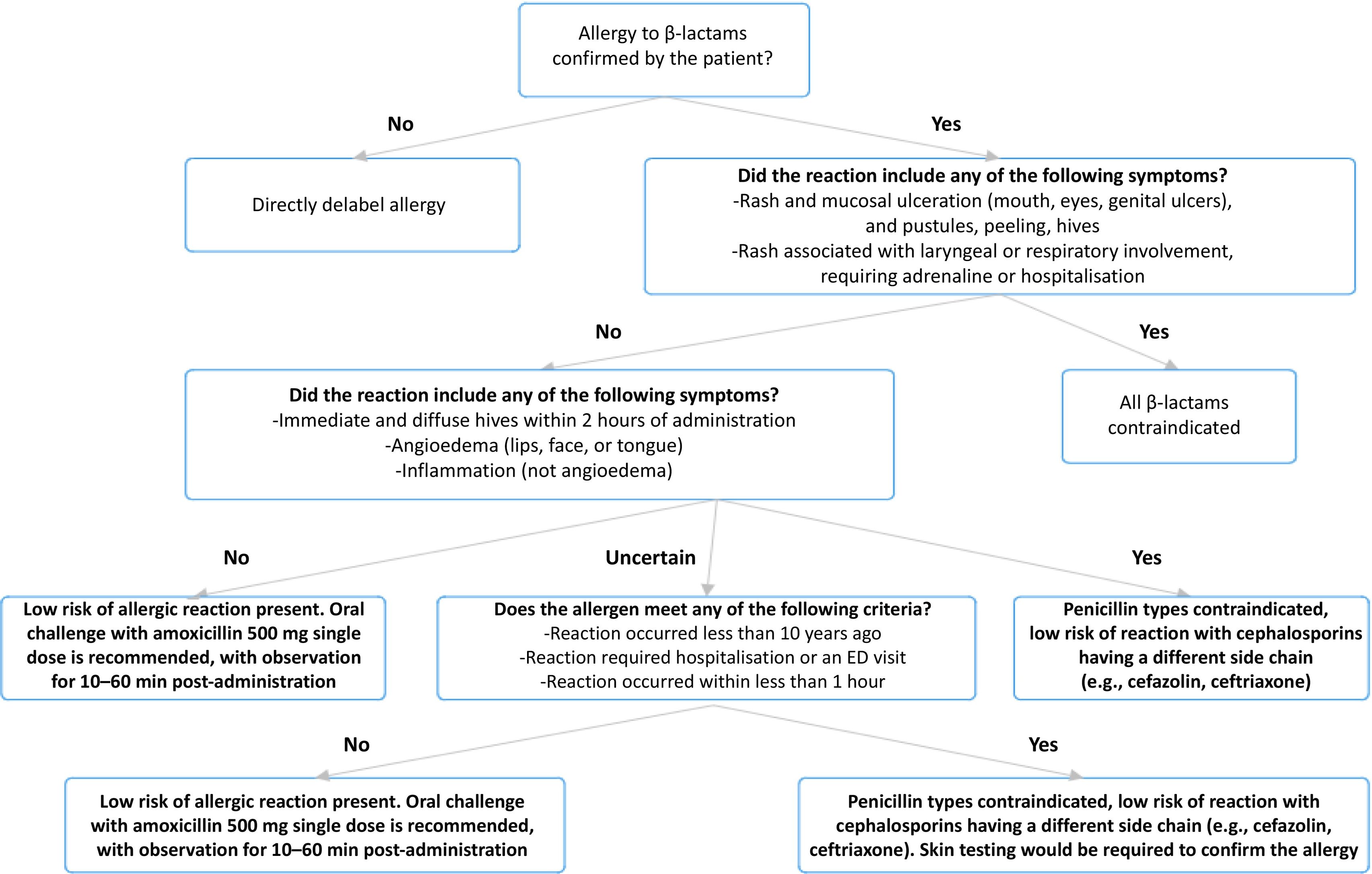

Intervention algorithmThe intervention algorithm was developed by the pharmacy service in consultation with the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program (ASP) team (see Fig. 1). This tool has been digitized and integrated with the electronic medical record system, enabling automated implementation and monitoring in the clinical setting. The following three tools were in used in the algorithm:

- •

Penicillin Allergy De-Labelling Toolkit: This toolkit provides structured guidance on assessing and potentially removing penicillin allergy labels.21

- •

Penicillin Allergy Decision Rule (PEN-FAST): This clinical decision-making instrument may help to classify patients according to their risk of having an actual penicillin allergy.22

- •

Antibiotic Allergy Assessment Tool: This tool helps to assess/classify allergies according to different phenotypes and previous allergic reactions, and to determine the best management strategy.23

The following demographic and clinical data were collected from patients: sex (nominal qualitative variable); age (continuous quantitative variable); allergy-triggering drug (nominal qualitative variable); type of allergy (nominal qualitative variable); previous allergy study (dichotomous qualitative variable [yes/no]); adequate documentation of the allergy in the medical record, including the offending drug, period of occurrence, signs and symptoms, and need for treatment (dichotomous qualitative variable [yes/no]); administration of penicillins after labeling (dichotomous qualitative variable [yes/no]); proposed action according to the algorithm (nominal qualitative variable); acceptance of the proposal (dichotomous qualitative variable [yes/no]); incidents related to the intervention (dichotomous qualitative variable [yes/no]); change of antibiotic after the intervention (dichotomous qualitative variable [yes/no]); and antibiotic initially prescribed (nominal qualitative variable).

These data were extracted from the patients' electronic medical records.

Descriptive statistical methods were used to analyze the collected data. Continuous variables are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables are expressed as relative frequencies. The analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (IBM, NY).

The identification, assessment, and intervention process comprised several steps:

Patient identification: A daily report was generated from the electronic medical record system to identify patients admitted to the ED with a penicillin allergy label who met the inclusion criteria.

Initial assessment: Three pharmacists—one of whom was a member of the ASP team—conducted an initial review of each patient's medical history to assess the relevance of the allergy label.

The previously mentioned clinical decision-making tools were used to develop an algorithm that was then employed to classify patients according to their allergy phenotype.21–23 This classification led to proposal of a specific intervention for each patient, which included options such as direct delabeling, referral to the allergy service for skin tests, oral challenge tests, or maintaining the allergy label.

Intervention and follow-up: The proposed action was recorded in the patient's medical record. The recommended intervention was then performed and shared with the medical team responsible for the patient. Patients were followed up to assess whether the proposal was accepted by the medical team and to identify any incidents related to the intervention. In addition, the patients were informed of the final proposal.

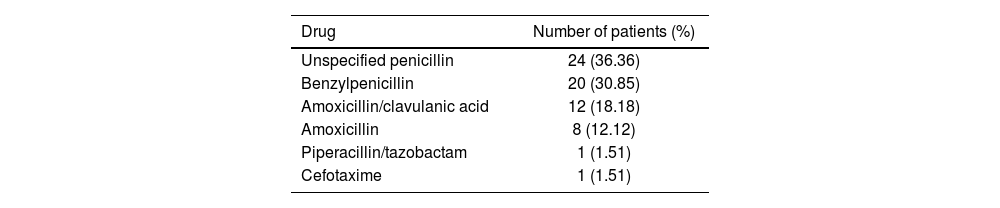

ResultsA total of 66 patients were evaluated. Of these, 30 (45.45%) were male and 36 (54.54%) were female. The median age was 77.38 years (IQR: 16.87). The drugs that prompted the initial allergy labelling were as follows: unspecified penicillin in 24 patients, benzylpenicillin in 20, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in 12, amoxicillin in 8, cefotaxime in 1, and piperacillin/tazobactam in 1 (see Table 1).

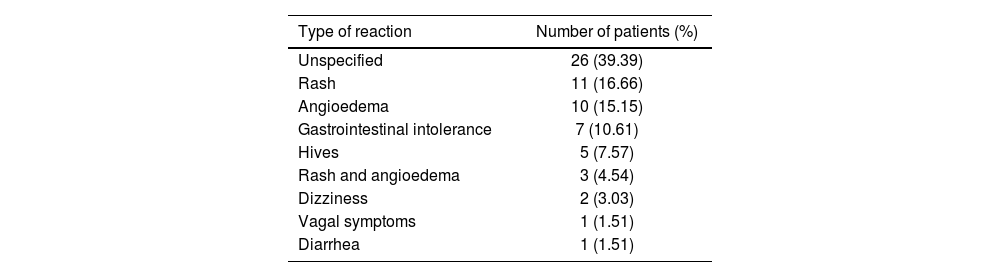

The allergic reactions reported varied: 26 patients experienced unspecified reactions; 11 had rash; 10 had angioedema; 7 had gastrointestinal intolerance; 5 had hives; 3 had both rash and angioedema; 2 had dizziness; 1 had vagal symptoms; and 1 had diarrhea (Table 2).

Of the total number of patients studied, 19 had previously undergone an allergy assessment; the allergy was adequately documented in 3 patients, and 50 had received penicillin after being labeled as allergic.

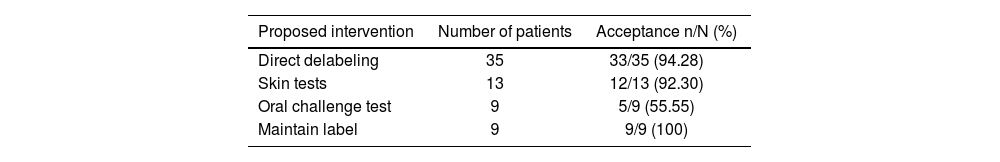

Based on the intervention algorithm, direct delabeling was proposed for 35 patients (53.03%), allergy confirmation through skin tests for 13 patients (19.69%), oral challenge tests for 9 patients (13.63%), and maintaining the allergy label for 9 patients (13.63%).

Of the 66 proposals made, 59 (89.39%) were accepted: 33/35 proposals for direct delabeling, 12/13 proposals for skin tests, 5/9 proposals for oral challenge tests, and 9/9 proposals to maintain the label. Finally, 42 (63.63%) patients were delabeled: 33 were directly delabeled, 2 through skin testing (10 patients are still awaiting testing at the time of writing), and 6 with negative oral challenge test results (see Table 3).

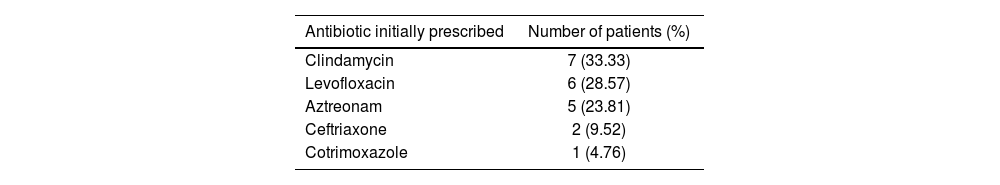

It is important to note thatt none of the patients who were delabeled experienced any incidents related to the intervention. The antibiotic therapy was changed after label assessment in 21 patients. The drugs initially prescribed were as follows: clindamycin in 7 patients; levofloxacin in 6; aztreonam in 5; ceftriaxone in 2; and cotrimoxazole in 1 (see Table 4).

DiscussionThis study demonstrates that an intervention algorithm is an effective and safe tool for assessing penicillin allergy labeling in a hospital setting. The implemention of the algorithm developed by the pharmacy service in collaboration with the ASP team significantly improved the management of penicillin allergy labelling and the antibiotic therapy received by these patients. The high acceptance rate of the intervention proposals (89.39%) indicates that the algorithm was well received by both healthcare professionals and patients. In particular, the acceptance rate for direct detachment was 94.28%, which suggests a high level of confidence in both the algorithm and the clinical assessment tools used. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies that have demonstrated the effectiveness of penicillin allergy detagging programs in reducing the inappropriate use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and improving clinical outcomes.15,24 Although antibiotic treatment was not modified for a significant number of patients following the delabeling process, the initial regimen was considered appropriate in many of these cases based on the patient's clinical progression or was in line with the center's ASP recommendations. Nevertheless, we consider delabeling to have a clinically relevant impact in the ED setting. On the one hand, it broadens the therapeutic options for potential subsequent treatment adjustments, whether due to clinical progression in the patient, the availability of microbiological results indicating targeted therapy, or the need to initiate or modify the antibiotic regimen upon hospital admission. In this sense, delabeling forms an ongoing part of the care process that can facilitate safer and more effective therapeutic decisions throughout the patient's treatment.

In general, allergies are not properly recorded, as shown by the fact that 95.46% of patients have inadequate allergy documentation in their medical records. This makes it difficult to assess them, which can result in mislabeling or suboptimal antibiotic treatment. Although a subgroup of patients had previously undergone allergy testing, they were included in the analysis because the allergy was still incorrectly documented in the medical record. The algorithm enabled a structured and up-to-date reassessment, which proved particularly pertinent for patients who had undergone tests many years earlier or who had ambiguous clinical information.

Our study provides an innovative approach to assessing penicillin allergies in emergency settings, as conducted by hospital pharmacists. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the effectiveness of a hospital pharmacist-led approach in the critical and dynamic context of hospital EDs. It shows how a well-designed algorithm, together with assessment by a pharmacist, can be effectively applied in time-critical situations. This not only introduces an additional layer of complexity but also underscores its usefulness in real clinical practice. Implementing the algorithm in ED settings enables rapid and accurate assessment of penicillin allergies, thus ensuring informed clinical decision-making. Reviewing penicillin allergy labeling during ED visits provides an opportunity to obtain up-to-date clinical information at the time of admission, allowing empirical and targeted antibiotic therapy to be adjusted, if necessary. In addition, it ensures that this information is available upon hospital discharge from EDs, thus ensuring the correct choice of treatment in the event of future clinical episodes.

These measures improve both the selection of the most appropriate antibiotic treatment for each patient and the safety of the treatment. It also has important economic implications, as it reduces the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and minimizes the length of hospital stays due to suboptimally treated infections.6,25

The preceding evidence demonstrates that these assessments can be integrated into a streamlined workflow without compromising patient safety, as demonstrated by the absence of incidents related to the interventions performed.

The findings of this study are consistent with those of previous research, which has shown that a significant number of patients labeled as penicillin-allergic can tolerate these antibiotics without experiencing any adverse effects.3,8 It has also been observed that up to 95% of patients labeled as allergic to penicillin are not actually allergic, underscoring the importance of reevaluating these labels in order to optimize antibiotic treatment.5

Numerous studies have also shown that implementing allergy assessment and detagging programs can significantly reduce the utilisation of alternative, less effective, and more expensive antibiotics, such as carbapenems and fluoroquinolones.24 This study corroborates these findings, demonstrating that a systematic, algorithm-based approach can be efficaciously implemented in a large hospital setting.

While the results are encouraging, it should be noted that this study is not without its limitations. Firstly, the retrospective design may have introduced bias as a result of the quality and availability of data contained in the electronic medical records. Due to the limited sample size, the findings are not generasible to other hospital settings. Therefore, studies conducted with larger samples and in different healthcare contexts are needed to validate these results. The limited availability of hospital pharmacists outside of the 8:00–16:00, Monday–Friday schedule, may have prevented penicillin allergy labels from being assessed for some patients during their ED stay. As skin testing is not available at our hospital, referrals to the allergology department were not made. Instead, an agreement was made to refer these patients to another hospital in the city with this medical specialty. However, at the end of this study, several patients were still awaiting skin testing to confirm or rule out this allergy. Although the intervention algorithm is based on previously validated tools, it has not itself been validated as an integrated tool. Therefore, external validation studies should be conducted.

Further research is recommended to evaluate the long-term impact of implementing the algorithm on bacterial resistance and treatment costs. It would also be beneficial to examine the use of artificial intelligence tools to facilitate the identification of suitable patients and automated decision-making, thereby reducing the time healthcare personnel need to spend on the task.

The results suggest that applying this algorithm in clinical practice could reduce the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and improve clinical outcomes. This highlights the relevance of hospital pharmacists in managing drug allergies.

Contribution to the scientific literatureThis study demonstrates the effectiveness and safety of an algorithm implemented by hospital pharmacists to reassess and correct penicillin allergy labels for patients admitted to EDs, thereby helping to optimize antibiotic use and improve patient safety.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe study was approved by the Drug Research Ethics Committee of the Fundació Assistencial Mútua Terrassa on February 26, 2025, under the reference number P/25–021/.

Declaration of authorshipFernando Salazar González and Mireia Iglesias Rodrigo (co-authors): study conception and design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and writing the article. Gemma Garreta Fontelles: study conception and design, critical review with relevant intellectual contributions, and approval of the final version for publication. Mireia Mensa Vendrell: critical review with relevant intellectual contributions, and approval of the final version for publication. Jordi Nicolás Picó: review of the manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statementFernando Salazar González: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mireia Iglesias Rodrigo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Gemma Garreta Fontelles: Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation. Mireia Mensa Vendrell: Validation, Supervision, Resources. Jordi Nicolás Picó: Validation.

FundingNone declared.

None declared.