This study reports on the results of a project conducted by the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy with patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, with the following objectives: to understand the experience of patients living with these diseases and the role of healthcare workers in such experience, and to identify opportunities to promote or boost humanization in hospital pharmacy units.

MethodA user-centered design methodology was used, implementing exploratory and qualitative research tools. Led by a managing team made up of experts in the methodology, a variety of people participated in this project. The team comprised representatives of patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, healthcare workers responsible for their care, members of the immune-mediated inflammatory disease working group of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy, and members of two patient advocacy organizations (Spanish Association of Persons with Chronic Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases and the Spanish Association of Patients with Psoriasis). The research tools used included in-depth interviews, patients’ diaries, ethnographic studies, and co-creation workshops.

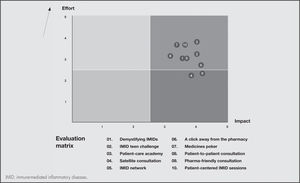

ResultsFive initiatives were identified as best practices to be implemented: The creation of functional or comprehensive care units; shared medical records; integration of patient-reported outcomes with patient experiences; implementation of the “capacity, motivation, opportunity” pharmaceutical care model; and a closer interaction with patient advocacy organizations. Six opportunities to improve the current situation were selected as priority areas for hospital pharmacy departments: spreading knowledge about immune-mediated inflammatory diseases; promoting a multidisciplinary approach to these diseases; generating awareness on the role of hospital pharmacists; revisiting the internal organization of pharmacy departments; establishing closer relationships with patients; and seeing things from the patients’ point of view. Ten smart humanization initiatives were proposed and classified in an impact-effort matrix: “Demystifying IMID”, “IMID teen challenge”, “Patient-care academy”, “Satellite consultation”, “IMID network”, “A click away from the pharmacy”, Medicines poker”, “Patient-to-patient consultation”, “Pharma-friendly consultation”, and “Patient-centered IMID sessions”.

ConclusionsThis Annex to the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy’s Guidelines for the Humanization of Hospital Pharmacy Units intends to promote a humanizing culture, bringing to the fore the unique value of every single patient suffering from an immune-mediated inflammatory disease, including their family and friends and their beliefs and needs, preserving their dignity.

Describir el proyecto de humanización para los pacientes con enfermedades inflamatorias mediadas por la inmunidad de la Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria encaminado a comprender la experiencia de los pacientes con enfermedades inmunomediadas inflamatorias, comprender el papel de los profesionales en la experiencia del paciente e identificar oportunidades para impulsar la humanización desde los servicios de farmacia hospitalaria.

MétodoSe empleó la metodología del diseño centrado en las personas, aplicando herramientas de investigación cualitativa y exploratoria. Participaron pacientes con enfermedades inflamatorias mediadas por la inmunidad, profesionales de todos los perfiles que les atienden, el Grupo de trabajo de Enfermedades Inmunomediadas Inflamatorias de la Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria y representantes de pacientes (Asociación de personas con enfermedades crónicas inflamatorias inmunomediadas y Asociación de pacientes Acción Psoriasis). Todo ello con la dirección de un equipo experto en diseño centrado en las personas. Entre las dinámicas empleadas se encuentran: entrevistas en profundidad, diarios de pacientes, observaciones etnográficas y talleres de cocreación.

ResultadosSe identificaron cinco iniciativas consideradas buenas prácticas a implementar (creación de unidades funcionales o de atención integrada, historia clínica compartida, integración de los resultados reportados por los pacientes y de su experiencia, modelo “capacidad, motivación y oportunidad” de atención farmacéutica y acercamiento a las asociaciones de pacientes). Se seleccionaron seis oportunidades sobre las que diseñar soluciones en los servicios de farmacia (favorecer el conocimiento de estas enfermedades, impulsar su abordaje multidisciplinar, difundir las atribuciones del farmacéutico de hospital, revisar la organización interna del servicio, establecer el vínculo con el paciente y adoptar la visión del paciente). Se propusieron diez grandes ideas para humanizar clasificadas en una matriz de impacto-esfuerzo (“Remitente IMID”, “IMID teen challenge“, “Escuela de familiares”, “Consulta satélite”, “Redemid”, “A un botón de farmacia”, “Póquer de fármacos”, “Consulta de paciente a paciente”, “Farma friendly”, “Sesiones IMID Patient-Centric”).

ConclusionesCon este anexo a la Guía de Humanización de la Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria se pretende promover una cultura de humanización, que ponga en valor a la persona que hay detrás de todo paciente con enfermedades inmunomediadas inflamatorias, teniendo en consideración su familia, entorno, creencias y necesidades y preservando su dignidad.

Over the last few years there has been a growing interest in developing processes and systems that place the patient at the center of health and social services. In the words of the Picker Principles, a “person-centered approach” places patients at the center, providing them with the care, support and education they need. According to this approach, users are recognized as individuals who are encouraged to play an active role in their care. The healthcare system should understand and respect their needs and preferences. Picker’s Eight Principles of Person-Centered Care, developed from original research with patients, their family members and healthcare providers, establish a framework designed to better understand most people’s priorities and what constitutes high-quality person-centered care1.

This approach is key to offer patients value-based care. However, gaining an understanding of such needs and preferences requires novel and creative strategies and the development of innovative and effective solutions adapted to each patient. In this regard, different organizations from the health sector have started to apply the so-called user-centered design (UCD) process to resolve complex issues, from process optimization to product design2–4. UCD can be defined as an iterative, collaborative and person-centered process employed to design products, services and systems. It has been claimed to be particularly appropriate for complex challenges5.

The Humanization movement has adopted the person-centered care principles to provide a holistic view that embraces all the stakeholders involved in the care process as well as their mutual interactions6. In short, the goal is to organize care around the person’s health needs and life expectations rather than around a disease.

In line with this goal, in June 2020, the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacists (SEFH) presented its Guidelines for the Humanization of Hospital Pharmacy Units (GHHPU)7, a project aimed at guiding hospital pharmacy units (HPUs) in creating and implementing humanizing initiatives, with an essentially practical orientation. Based on the UCD methodology, the project benefited from the active participation of both healthcare professionals and patients. The most ambitious goal of the GHHPU was to get all HPUs in Spain to embrace it, thus incorporating humanization as a pivotal strategy. The GHHPU could also be used to design and improve the quality of care provided to the patients who participated in their preparation, who were afflicted with a wide range of conditions including infectious, hematooncological, pediatric, rare and complex chronic diseases. The GHHPU have always been understood as a living document, which would feed on the experience gained through other projects. It is with this spirit in mind that it was recently decided to extend their recommendations to patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) by adding an specific Annex to this effect.

The purpose of this study was to describe SEFH’s specific humanization project for IMID patients, which is geared toward gaining an insight into the experience of patients with IMIDs, understanding the role healthcare professionals play in shaping the experience of IMID patients, and identifying ways in which HPUs can promote humanization.

MethodA UCD-based methodology was selected, comprising both qualitative and exploratory research tools. The methodology was designed based on the active collaboration of patients diagnosed with an IMID; the healthcare providers in charge of their care (hospital pharmacists; physicians specializing in gastroenterology, rheumatology, dermatology, the Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis, nursing staff and psychologists); SEFH’s Working Group on Inflammatory Diseases; and patient representatives (Spanish Association of Persons with Chronic Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases and the Spanish Association of Patients with Psoriasis). The work was carried out under the supervision and with the support of a team of strategic designers specializing in UCD.

Table 1 shows the project’s roadmap and provides a sequential description of the dynamics used for the development of the present Annex.

Description of the activities carried out under the project

| Activity | Description |

|---|---|

| Kick-off workshop | Identification of relevant information that may serve as a starting point for the design of a research script adjusted to the project's context. By means of different activities and tools, a map of the system was built and a series of patient typologies were identified that were used to plan the patient onboarding process. |

| In-depth interviews | Through open and semi-structured questions, this technique makes it possible to select a group of people who are then asked to talk about their experiences, expectations, motivations and needs with respect to a topic proposed by the design team further to the results of the kick-off workshop and of a documentary analysis. |

| Patient diaries | This tool provides information about patients' day-to-day lives placing particular emphasis on the influence of their disease on their emotions, difficulties, needs, etc. Patients were asked to involve the care team in their day-to-day lives by sending in comments, photographs, videos, etc that may provide an understanding of how the disease impacted on their lives. |

| Ethnographic observations | This qualitative research technique is aimed at complementing and verifying the information obtained from other techniques and tools applied. During the observation process, informants are accompanied in the performance of their tasks and their interaction with others using the resources available at the site where the observation takes place. |

| Definitions workshop | Once the investigation process was completed, the researchers submitted the results of their work to the project team. At this stage, new perspectives were contributed and a series of challenging questions were developed that were fed into the second phase of the project: the co-creation phase. |

| Co-creation workshop | This was a joint work session between patients and health professionals where participants had to make use of their creativity to take their thoughts to unchartered territories. This exploratory phase served as a platform to develop solutions to the proposed challenges. |

| Prototyping workshop | This was a joint work session between patients and health professionals intended to conceptually develop the ideas contributed. Using a storyboard, participants developed solutions with a prototyping tool that made it possible to transform ideas into tangible realities. |

| Development sprint | The project team, together with the design team, worked together on a series of iterations of the final document that became the Annex. |

The information obtained was grouped into three sections, replicating the structure of SEFH’s GHHPU:

- 1.

Vision: It is defined in the GHHPU by means of the Eight Humanization Principles.

- 2.

Initial situation of patients with IMID: This is a set of different critical scenarios related with IMIDs as seen from the point of view of patients and health professionals. The investigation helped the team propose different solutions for enhanced humanization. Some best practices were also identified, which can be used by hospital pharmacists and other professionals to embrace humanization when dealing with this group of patients.

- 3.

Toolkit for humanizing HPUs: This is a set of tools designed to help address the challenge of humanization. In addition to the tools contained in the GHHPU (humanization profile, blueprint, and 50 humanization initiatives), a new tool was put together (the Patient Journey Map) as well as a group of 10 specific initiatives for patients with IMID, prioritized in an impact effort matrix and described in factsheet form foe easier implementation.

Table 2 summarizes the initial situation of patients with IMID in terms of the experiences or circumstances mentioned by the participants.

Initial situation: summary of the experiences or circumstances expressed by participants and humanization opportunities in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases patients

| Circumstances expressed by patients | ||

|---|---|---|

| Experiences of IMID patients | IMID patients feel their case is different from anybody else's | Patients consider IMIDs to be rare and socially unrecognized conditions. They believe their cases are unique and feel nobody understands them as, on occasion, people around them criticize them for exaggerating their suffering. |

| Guilt feelings and healing through discipline | Patients suffer from a chronic condition for which they partly consider themselves responsible as they tend to attribute it to their own personal circumstances. This supposed responsibility sometimes induces a feeling of guilt, particularly when new symptoms appear. | |

| IMIDs result in social estrangement | Patients feel they are subject to the judgement of their family and friends. This increases the feeling that they are “the odd man out” and drives them to self-isolation. | |

| Patients demand a holistic approach | Patients want to feel that the different specialists in charge of their case communicate with one another. They tend to adopt a cross-sectional view and expect their own personal experience to be taken into consideration as they regard themselves as experts in their daily disease process. | |

| Treatment | Uncertainty and mistrust with regard to the treatment | Some of the visits of IMID patients to the hospital pharmacy unit may result from a worsening of their condition and it is not uncommon for them to have doubts about the efficacy of their treatment at this point. |

| Is the treatment making me weaker? | IMID patients know that their treatment weakens their immune system. This makes them feel vulnerable and could make them decide to abandon their treatment thinking that this may protect them. | |

| Pharmacy department | The Hospital Pharmacy Unit should be a place where patients feel welcome rather than just a drug dispensing point | At times patients may feel that their relationship with the hospital pharmacy unit is merely mechanical, consisting basically in being dispensed their medications following an interview with the pharmacist, which typically takes place at the beginning of their treatment or when their medication is switched. |

| Hospital pharmacists: the invisible professionals | The organization of hospital pharmacy departments into different areas of specialization has improved the patients' experience but, at the same time, new challenges are involved. Clinical records do not always make reference to the pharmaceutical interview, which adds to the invisibility of hospital pharmacists as compared with other healthcare professionals. | |

| Telepharmacy: the missing link | Patients that have availed themself of telepharmcy are generally satisfied with the service. However, it would be desirable for patients to be required to schedule their telepharmacy appointments so as to maximize the effectiveness of the service for both hospital pharmacists and patients. | |

IMID: immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.

Five initiatives were identified, regarded as best practices to be implemented in this group of patients:

- 1.

Establishment of functional or integrated care units: Hospital do not always find it easy to coordinate the different patient-centered services they offer to ensure a right delivery of care. In order to improve this situation, different centers have implemented functional patient-centered structures aimed at coordinating the work of healthcare professionals around IMIDs so as to enable an effective use of the available resources and improve the patients’ experience and health outcomes8.

- 2.

Shared clinical records: Access of hospital pharmacists to the clinical records of patients with IMIDs is crucial. Indeed, a team made up of professionals with different backgrounds enriches the work of the multidisciplinary team and results in an improvement of the standard of care delivered to the patient. Under the shared clinical records scheme, HPUs can contribute valuable information related, for example, with Patient-Reported Experience Measures (PREMs) and Patient Reported Outcomes Measures (PROMs).

- 3.

Integration of PROMs and PREMs: Value-based healthcare involves a paradigm shift based on embracing a new approach geared towards achieving the best health outcomes at the lowest cost, maintaining high levels of efficient and taking into consideration the outcomes that patients care most about8,9.

- 4.

The CMO model: The CMO model (Capacity, Motivation, Opportunity) for IMIDs seeks a reconfiguration of outpatient pharmaceutical practice. It is based on the three basic qualities that define the pharmaceutical care model advocated by SEFH, which responds to the current challenges and needs of patients, the health system and society at large10.

- 5.

Interaction with IMID patient organizations: Patient organizations have a great deal to contribute. Their expertise can help improve the way patients are taken care of, which can result in higher levels of satisfaction and, consequently, better health outcomes11.

Six opportunities were detected around which to design solutions:

- 1.

Promoting knowledge about IMIDs: Patients consider that neither society in general nor their immediate circle understand the nature of their disease or its repercussions. Patients also tend to believe that IMIDs are rare, chronic diseases associated with a short life expectancy.

- 2.

Fostering a multidisciplinary approach to IMIDs: At the present time, the fragmentation of information across different hospital units makes it necessary for patients to act as a link between the different professionals involved in their treatment.

- 3.

Publicizing the competencies of hospital pharmacists: Although HPUs are integrated within the hospitals’ structure, there is a dearth of information about their capabilities, particularly those concerning the counseling of IMID patients.

- 4.

Reviewing the internal organization of HPUs: HPUs have in recent years experienced a significant internal evolution, which has resulted in them being organized into different specialties. Although this change has increased efficiency, it is essential to prevent it from negatively affecting the care provided to patients with IMIDs.

- 5.

Connecting with the patient: Although patients claim to be satisfied with the work of HPUs, they tend to identify them with a “medicine dispensation office”, and state that they only interact with pharmacists at the beginning of their treatment. They also express their wish to be assigned a pharmacist who specializes in IMIDs.

- 6.

Adopting the perspective of IMID patients: Patients have resigned themselves to long waits, unexpected calls, the impossibility of resolving doubts on the spur of the moment, long intervals between appointments, being seen to by someone different every time, and the difficulty of locating the HPU, which is often in remote or difficult-to-access areas. This situation needs to be reevaluated so as to more effectively meet the needs of patients with IMIDs.

Finally, ten smart humanization initiatives were proposed based on the previous work carried out. They were classified in an impact-effort matrix (Figure 1):

- –

01. Demystifying IMIDs: Testimonials from expert patients intended to dispel the common feeling among patients that their case is worse than everybody else’s and address their mistrust regarding their treatment.

- –

02. IMID teen challenge: A gamified interview format, specifically designed for adolescent patients.

- –

03. Patient-care academy: A patient-managed academy where family members are made aware of the specificities of IMIDs. It is a space where patients’ family members are given details about IMIDs and about the impact of the disease on the patients’ and their own lives, beyond the most critical episodes.

- –

04. Satellite consultation: An informal gathering of patients with IMIDs, medical specialists and nursing staff intended to drive home the significance of hospital pharmacists as the professionals in charge of delivering the medications they need for their treatment, and the importance of interacting with hospital pharmacists in case of emergency.

- –

05. IMID network: This is an information-sharing network, coordinated by SEFH’s IMID Working Group, where HPUs can exchange information about IMID treatments. The network facilitates access to information on innovative treatments, making it available to all HPUs. Each unit constitutes an active node in a network dedicated to offering solutions.

- –

06. A click away from the pharmacy: Direct real-time (physical or virtual) access point, from which medical specialists alert HPUs of a need for interaction. The purpose of the system is to facilitates communication.

- –

07. Medicines poker: This is a series of informative materials presented as a deck of cards of three suits: DMDs (disease-modifying drugs), small oral disease-modifying molecules, and biologic drugs. An initial flashcard shows the characteristics shared by each suit as well as their potential benefits and drawbacks. These materials are developed by HPUs with the support of medical specialists and nursing staff, with the potential collaboration of other professionals such as psychologists or nutritionists.

- –

08. Patient-to-patient consultation: A format that brings together IMID patients and IMID patient associations, led by expert patients connected with the associations.

- –

09. Pharma-friendly consultation: A consultation specifically designed for IMID patients presenting to the HPU for the first time.

- –

10. Patient-centered IMID sessions: These are HPU-led sessions where IMID patients and the healthcare providers involved in their treatment are brought together to spearhead the creation of cross-sectional functional units that place IMID patients at the center of the care process.

Humanization of care is a complex challenge requiring a multidisciplinary approach. It is intended to ensure that patients are provided with comprehensive information on their disease, take more responsibility for their condition, make the necessary changes to their lifestyles and improve their adherence to their medication. Hospital pharmacists are well-equipped to play an active role in improving humanization, offering information about diseases and their treatment, fostering shared decision-making, adapting healthcare circuits to the patients’ needs, and improving patients’ access to and satisfaction with consultations, day hospitals, etc.

IMID patients are among the most vulnerable ones, and typically experience a reduction in their quality of life in the physical, psychological and social domains, with a significant deterioration of their social and work relationships, among others12,13.

The project described in this article helped identify a series of best practices that should be extended to the care of all patients with IMIDs. Integrated care units seek to adapt healthcare and psychosocial interventions to the patients’ situation, empowering them to participate in the identification of their own needs and in the selection of treatment strategies based on the goals of their therapy. To do that:

- •

Patient education must be enhanced making sure patients feel they too are responsible for the management of their condition.

- •

Healthcare education activities should be organized, focusing on health promotion and prevention measures adapted to patients and their environment.

- •

The participation, commitment and leadership of the healthcare professionals involved are essential to support the development and evolution of the model.

- •

A clear identification of those responsible for the different processes and subprocesses is required.

A successful example of this integrated model is the Center for Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases of the Gregorio Marañón General University Hospital, whose mission is to “improve the health and quality of life of persons with IMID through specialized and innovative healthcare and clinical services based on new patient-centered care models, characterized by technical and human excellence and inspired by research and development”. This mission statement clearly embodies the philosophy inherent in the care model advocated in this article.

Improving patients’ function and wellbeing should be a fundamental goal of healthcare, particularly in the later stages of life, characterized by a higher prevalence of chronic conditions. In the specific case of IMID patients, disability and reduced quality of life are very significant aspects that should be measured and evaluated to take the steps required to limit their impact. A PROM-based approach is a significant step in this direction, provided that the patients’ perspective is taken into consideration. However, PREMs must also be included as they measure important aspects about perceived quality in healthcare, including treatments and the support provided, and are a valuable complement to PROMs as indispensable healthcare quality indicators. In Spain, all these procedures must be aligned with SEFH’s MAPEX initiative, according to which the work of hospital pharmacists should adopt a patient- and health-outcomes-centered perspective. At the same time, stratification of outcomes provides for an efficient management of healthcare, where technology and, particularly, ePROMs play a crucial role in a process that is driven by digitalization.

It is essential for any initiative, project or process to meet the needs of patients and be attuned to their circumstances. For that reason, both patients and the organizations that represent them must be involved in the design of healthcare processes as this is bound to bring about a real change in the structure of public policies, in the organization and management of healthcare, and in the healthcare provider-patient relationship.

Working in the field of humanization means understanding the need to ensure that every human being, particularly the most vulnerable ones, are treated with dignity. In this regard, we still have a long way to go, hand in hand with IMID patients14.

In a context dominated by value-based medicine, listening to and empathizing with patients, and taking into account their points of view is an indispensable requirement, inherent in an inclusive healthcare model that effectively places the patient at the very center of the system. To achieve that goal, the care delivered to patients with IMIDs should be based on a collaborative cross-sectional model. We all need to learn to listen, understand and share, on top of more usual activities like informing, instructing and educating.

Humanized healthcare should place less emphasis on efficiency and shift its focus toward the more humane components of healthcare, trying to strike a balance that brings scientific evidence closer to each patient’s persona, thereby boosting clinical effectiveness.

In this regard, Picker’s Eight Principles of Patient-Centered Care1 are of paramount importance:

- 1.

Respect for patients’ values, preferences and needs.

- 2.

Coordination and integration of care.

- 3.

Ensuring availability of clear, easy-to-understand and relevant information.

- 4.

Maximizing quality of life, especially regarding pain control.

- 5.

Emotional support and alleviation of fear and anxiety.

- 6.

Involving family and friends in the process to the extent that patients consider it necessary.

- 7.

Receiving continued care regardless of where it is administered.

- 8.

Maximizing accessibility to required services.

SEFH, for its part, defined its view on humanization through eight principles7 (Table 3).

Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacists's Guidelines for the Humanization of Hospital Pharmacy Units

| Humanization principies |

|---|

|

An example of this will to promote a paradigm shift is to be found in a recent Danish randomized study by Hjuler et al.15, which sets about demonstrating that coordinated multidisciplinary work with IMID patients is more effective than standard management, resulting in fewer symptoms and better patient-reported outcomes, which is aligned with the goals of humanized patient care.

In short, this Annex to SEFH’s GHHPU seeks to promote a humanization culture that recognizes the values of the human being that lies behind every IMID patient, taking into consideration their family, the environment around them, and their beliefs, needs and dignity.

FundingThis project was promoted by the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacists and sponsored by Janssen through a collaboration agreement.

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to thank the patients and professionals who participated in the project. The patients’ identity is not disclosed out of respect for their privacy. A special thank you goes to the professionals on the core working group: Carina Escobar Manero, Juan Carlos Torre Alonso, Laura Marín Sánchez, Pablo de la Cueva Dobao and Miquel Sans Cuffí; to those in the extended working group: Daniel Ginard Vicens, José Luis Sánchez

Carazo, Sandra Ros Abarca and Santiago Alfonso Zamora; and to those on the oopen Diseño Estratégico S.L team: Gelo Álvarez, Jesús Sotelo, Nacho Álvarez, María Calabuig, and Irene Porro.

Conflict of interestThe Pharmacy Department of the Ramón y Cajal Hospital benefits from a grant for preparing an overall humanization project for the Department under an institutional agreement.

Presentation at congressesThe project was preented at a webinar organized by SEFH and is due to be published on the website of SEFH’s Guidelines for the Humanization of Hospital Pharmacy Units.

Contribution to the scientific literatureThis is the first user-centered design-based project that describes the needs of patients with immune-mediated inflammatory conditions.

This is an innovative project aimed at enriching SEFH’s Guidelines for the Humanization of Hospital Pharmacy Units, proposing solutions intended to improve humanization of pharmacy units and the care they provide to their patients.

Early Access date (11/14/2022).