To describe the process of implementing a traceability and safe manufacturing system in the clean room of a pharmacy service to increase patient safety, in accordance with current legislation.

MethodsThe process was carried out between September 2021 and July 2022. The software program integrated all the recommended stages of the manufacturing process outlined in the “Good Practices Guide for Medication Preparation in Pharmacy Services” (GBPP). The following sections were parameterised in the software program: personnel, facilities, equipment, starting materials, packaging materials, standardised work procedures, and quality controls.

ResultsA total of 50 users, 4 elaboration areas and 113 equipments were included. 435 components were parameterized (195 raw materials and 240 pharmaceutical specialties), 54 packaging materials, 376 standardised work procedures (123 of them corresponding to sterile medicines and 253 to non-sterile medicines, of which 52 non-sterile were dangerous), in addition, 17 were high risk, 327 medium risk, and 32 low risk, and 13 quality controls.

ConclusionsThe computerization of the production process has allowed the implementation of a traceability and secure manufacturing system in a controlled environment in accordance with current legislation.

describir el proceso de implantación de un sistema de trazabilidad y elaboración segura en la sala blanca de un Servicio de Farmacia para incrementar la seguridad en el paciente, cumpliendo la legislación vigente.

Métodoel proceso se llevó a cabo entre septiembre de 2.021 y julio de 2.022. El programa informático integró todas las fases del proceso de elaboración que se recomiendan en la «Guía de Buenas Prácticas de preparación de medicamentos en los Servicios de Farmacia» (GBBPP). Se parametrizaron los siguientes apartados en el programa informático: personal, instalaciones, equipos, materiales de partida, material de acondicionamiento, procedimientos normalizados de trabajo y controles de calidad.

Resultadosse incluyeron un total de 50 usuarios, 4 zonas de elaboración y 113 equipos. Se parametrizaron 435 componentes (195 materias primas y 240 especialidades farmacéuticas), 54 materiales de acondicionamiento, 376 procedimientos normalizados de trabajo (123 de ellos correspondientes a medicamentos estériles y 253 a medicamentos no estériles, de los cuales 52 no estériles eran peligrosos), además 17 eran de alto riesgo, 327 de riesgo medio y 32 de riesgo bajo, y 13 controles de calidad.

Conclusionesla informatización del proceso de elaboración ha permitido la implantación de un sistema de trazabilidad y elaboración segura en sala blanca, que cumple con la legislación vigente.

The therapeutic arsenal continues to expand daily as we learn more about various diseases, with the aim of preventing or treating them. However, in certain cases, commercially available medicines do not meet treatment needs, particularly in paediatric settings. Children can face challenges such as swallowing difficulties, metabolic and neurological conditions necessitating invasive devices like catheters, and dosages that do not match the available formulations.1

To address such issues, existing medicines need to be tailored to the needs of individual patients, while maintaining high standards of quality and safety. Guidelines to ensure quality and safety in the preparation of medicinal products in hospitals have been provided through European legislation in the form of the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) “Guide to Good Practices for the Preparation of Medicinal Products in Healthcare Establishments”,2 and through Spanish legislation in the form of Royal Decree 16/2012 of 20 April 2012 on the Handling and Suitability of Medicinal Preparations3 and Royal Decree 175/2001, approving the “Rules for the correct preparation and quality control of magistral formulas and official preparations”.4

In 2014, the Spanish Ministry of Health published the “Guide to Good Practice in the Preparation of Medicines in Hospital Pharmacy Services” (Spanish acronym: GBBPP),5 aiming to harmonise existing recommendations. In 2022, the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH) also published a document on the traceability and safe use of medicines in hospitals,6 highlighting improvements in efficiency and safety by applying traceability through the application of technologies such as electronic prescribing and automated dispensing systems.

The aim of this study was to describe the process of implementing a traceability and safety system in the drug preparation area within a clean room of a pharmacy service in accordance with current regulations.

MethodsThe implementation process was conducted between September 2021 and July 2022, commencing with a first phase for non-sterile preparations, followed by a second phase for sterile preparations.

The software was configured based on the chapters of the GBBPP.5

StaffThe personal data (name, surname, and Spanish National Identity Number) of all drug preparers were recorded and they were categorised according to a defined level of responsibility.

Facilities and equipmentThe characteristics of the facilities and the various medicine preparation areas were defined.

A file was created for each piece of equipment containing details of the name, model, serial number, manufacturer, revision record, and user manual.

Raw materials and packaging materialsThe following characteristics were defined for the raw materials and pharmaceutical products: active ingredient, presentation, trade name, manufacturer, usual supplier, technical data sheet, national code, barcode or manufacturer's 2D code (datamatrix), storage, location, accounting unit (grams, tablets, capsules, vials, etc), quantity per container, dosage per unit, physical state, hazard level according to the recommendations of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and type of label.

The characteristics were also defined of all available packaging materials.

Preparation and standard operating proceduresAll standard operating procedures (SOPs) for medicines prepared by the pharmacy service were parameterised. The following details were recorded for each procedure: name of the preparation (active ingredient, dose or concentration, and pharmaceutical form), whether it was a sterile or non-sterile preparation, risk level according to the GBBPP risk matrix, category of the preparation staff, preparation area, equipment used, work protocol, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) group, type of patient for whom it is dispensed, raw materials and quantity, pharmaceutical form and route of administration, storage requirements, expiry date, quality controls, packaging material, excipients subject to notification, references, authors, observations, and galenic validation. Each protocol had to be validated by a pharmacist.

Quality controlsThe quality controls were parameterised according to the recommendations of the GBBPP and the Spanish National Formulary, depending on the type of preparation. The monograph from the Spanish National Formulary monograph containing the described controls was attached.

ResultsStaffA total of 50 users were parameterised, comprising 21 pharmacists, 25 nurses, 3 pharmacy technicians, and 1 computer technician, each with a different level of responsibility.

Facilities and equipmentFour preparation areas were defined: pharmacotechnical laboratory, oral hazards preparation area, horizontal laminar flow cabinet room, and vertical laminar flow cabinet room. The first 2 areas are classified as class C and the last 2 areas as class B.

A total of 113 pieces of equipment were parameterised, comprising 6 balances, 5 cabinets, 11 computers, 7 printers, 4 optical readers, 33 laboratory materials, and 47 consumables. We recorded the location and type of cabinets, including 2 vertical laminar flow cabinets, 2 horizontal laminar flow cabinets, and a type 1 biosafety cabinet.

Raw materials and packaging materialsA total of 435 components were parameterised, of which 195 were raw materials and 240 were pharmaceutical specialities. In total, 8.5% of the starting materials were hazardous.

The datamatrix code was entered for all raw materials and pharmaceutical specialities to ensure traceability and safety in the preparation process.

A total of 54 packaging materials were also parameterised.

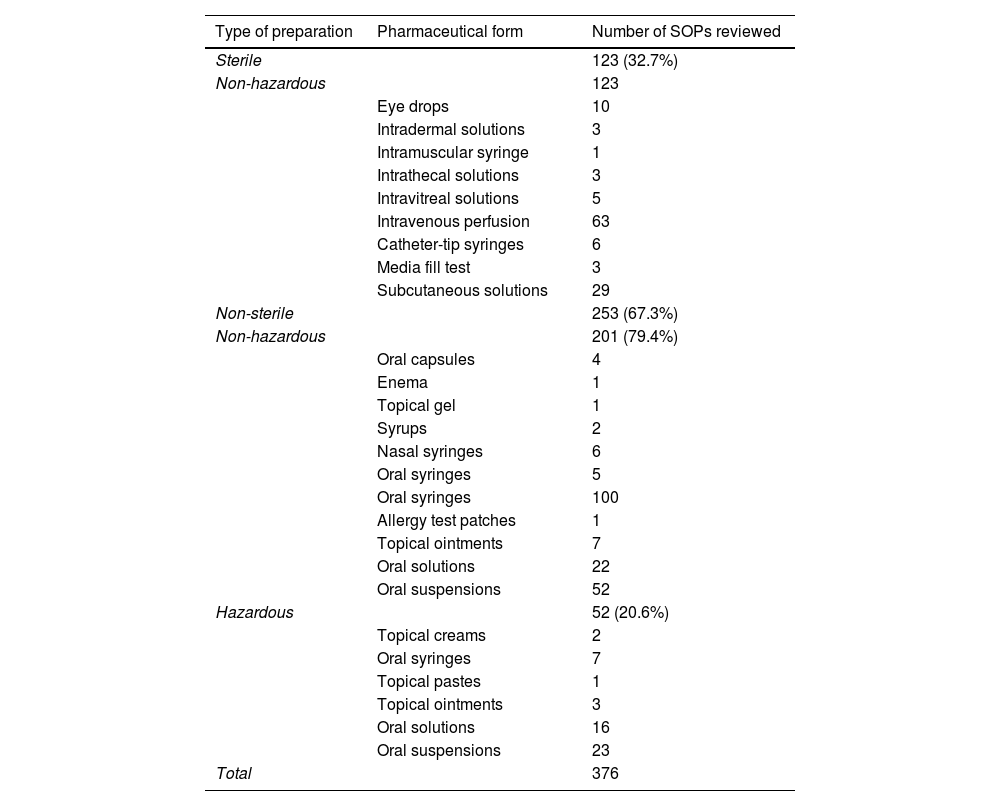

Preparation and standard operating proceduresA total of 376 SOPs were parameterised (Table 1), of which 123 (32.7%) addressed sterile preparations. Hazardous sterile preparations were not included because their preparation is managed by a different software programme.

Total number of SOPs for non-sterile preparations classified by dosage form and hazard.

| Type of preparation | Pharmaceutical form | Number of SOPs reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| Sterile | 123 (32.7%) | |

| Non-hazardous | 123 | |

| Eye drops | 10 | |

| Intradermal solutions | 3 | |

| Intramuscular syringe | 1 | |

| Intrathecal solutions | 3 | |

| Intravitreal solutions | 5 | |

| Intravenous perfusion | 63 | |

| Catheter-tip syringes | 6 | |

| Media fill test | 3 | |

| Subcutaneous solutions | 29 | |

| Non-sterile | 253 (67.3%) | |

| Non-hazardous | 201 (79.4%) | |

| Oral capsules | 4 | |

| Enema | 1 | |

| Topical gel | 1 | |

| Syrups | 2 | |

| Nasal syringes | 6 | |

| Oral syringes | 5 | |

| Oral syringes | 100 | |

| Allergy test patches | 1 | |

| Topical ointments | 7 | |

| Oral solutions | 22 | |

| Oral suspensions | 52 | |

| Hazardous | 52 (20.6%) | |

| Topical creams | 2 | |

| Oral syringes | 7 | |

| Topical pastes | 1 | |

| Topical ointments | 3 | |

| Oral solutions | 16 | |

| Oral suspensions | 23 | |

| Total | 376 |

Abbreviation: SOPs, standard operating procedures.

Of the procedures, 67.3% were non-sterile, with 80% of these involving non-hazardous active ingredients.

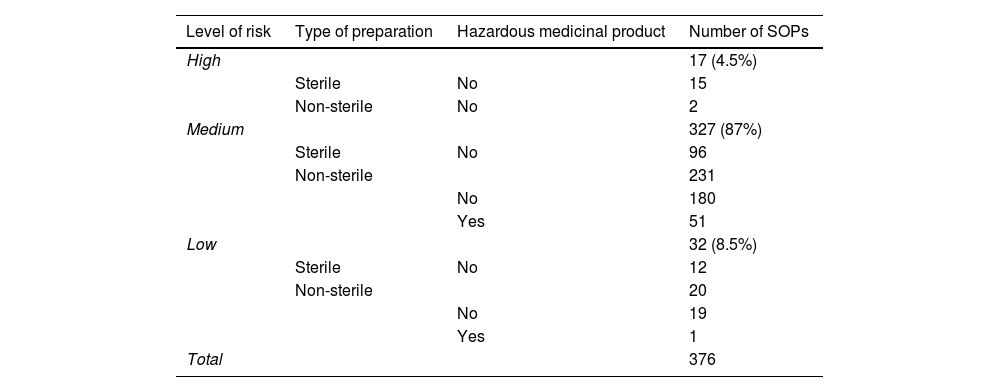

In turn, the application of the risk matrix for sterile and non-sterile preparations of the GBBPP shows that of the 376 parameterised SOPs, 17 (4.5%) were categorised as high risk, 327 (87%) as medium risk, and 32 (8.5%) as low risk. Table 2 shows a more detailed breakdown of the types of preparations by risk level.

Number and type of preparations by risk level.

| Level of risk | Type of preparation | Hazardous medicinal product | Number of SOPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | 17 (4.5%) | ||

| Sterile | No | 15 | |

| Non-sterile | No | 2 | |

| Medium | 327 (87%) | ||

| Sterile | No | 96 | |

| Non-sterile | 231 | ||

| No | 180 | ||

| Yes | 51 | ||

| Low | 32 (8.5%) | ||

| Sterile | No | 12 | |

| Non-sterile | 20 | ||

| No | 19 | ||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| Total | 376 |

Abbreviation: SOPs, standard operating procedures.

For each SOP, we recorded data related to the most common type of patient for whom the preparation is dispensed: outpatient, inpatient, pharmacotechnical store, general store, home care, palliative care, medical day hospital, home hospitalisation unit, and oncology day hospital.

Quality controlsA total of 13 quality controls were recorded, to be conducted by the preparation staff or by the pharmacists validating each preparation. As indicated in the GBBPP and the National Formulary, non-sterile preparations should undergo checks for pH, final appearance, and organoleptic characteristics. Sterile preparations require gravimetric control, as well as checks for clarity and final appearance.

DiscussionAll medicines produced by pharmacy services must be safe and effective. To this end, Spanish and European regulations must be followed.

Pharmacists are technically responsible for preparing medicines and must take the actions needed to ensure that preparations are suitable for use, safe, effective, and meet defined quality standards. Hence, the computerisation of the preparation process will enable and facilitate the achievement of all these objectives.

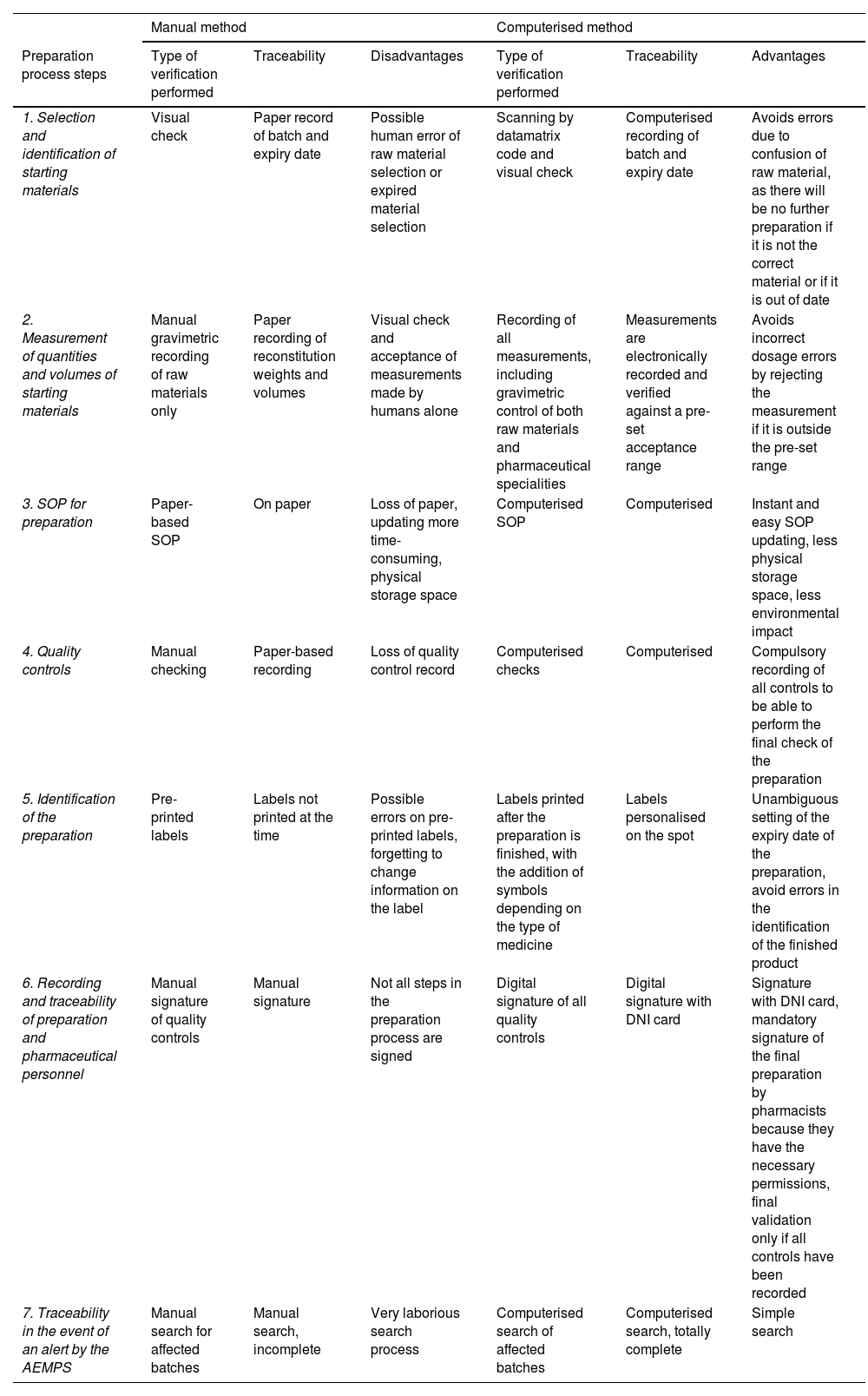

An advantage of computerisation in the preparation area is the complete traceability of the final product, from the preparation order to the final pharmaceutical validation (Table 3).

Comparison of manual and computerised workflow preparation and traceability systems.

| Manual method | Computerised method | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation process steps | Type of verification performed | Traceability | Disadvantages | Type of verification performed | Traceability | Advantages |

| 1. Selection and identification of starting materials | Visual check | Paper record of batch and expiry date | Possible human error of raw material selection or expired material selection | Scanning by datamatrix code and visual check | Computerised recording of batch and expiry date | Avoids errors due to confusion of raw material, as there will be no further preparation if it is not the correct material or if it is out of date |

| 2. Measurement of quantities and volumes of starting materials | Manual gravimetric recording of raw materials only | Paper recording of reconstitution weights and volumes | Visual check and acceptance of measurements made by humans alone | Recording of all measurements, including gravimetric control of both raw materials and pharmaceutical specialities | Measurements are electronically recorded and verified against a pre-set acceptance range | Avoids incorrect dosage errors by rejecting the measurement if it is outside the pre-set range |

| 3. SOP for preparation | Paper-based SOP | On paper | Loss of paper, updating more time-consuming, physical storage space | Computerised SOP | Computerised | Instant and easy SOP updating, less physical storage space, less environmental impact |

| 4. Quality controls | Manual checking | Paper-based recording | Loss of quality control record | Computerised checks | Computerised | Compulsory recording of all controls to be able to perform the final check of the preparation |

| 5. Identification of the preparation | Pre-printed labels | Labels not printed at the time | Possible errors on pre-printed labels, forgetting to change information on the label | Labels printed after the preparation is finished, with the addition of symbols depending on the type of medicine | Labels personalised on the spot | Unambiguous setting of the expiry date of the preparation, avoid errors in the identification of the finished product |

| 6. Recording and traceability of preparation and pharmaceutical personnel | Manual signature of quality controls | Manual signature | Not all steps in the preparation process are signed | Digital signature of all quality controls | Digital signature with DNI card | Signature with DNI card, mandatory signature of the final preparation by pharmacists because they have the necessary permissions, final validation only if all controls have been recorded |

| 7. Traceability in the event of an alert by the AEMPS | Manual search for affected batches | Manual search, incomplete | Very laborious search process | Computerised search of affected batches | Computerised search, totally complete | Simple search |

Abbreviations: AEMPS, Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products; DNI, Spanish national identity number; SOPs, standard operating procedures.

One of the strengths of the study is that the results obtained are real-world data collected from the preparation area of a hospital pharmacy service. These results also represent initial data on implementing a computerised system for the safe preparation of medicines in a clean room within a Spanish pharmacy service. These data could potentially aid in the adoption of this system in other pharmacy services.

Limitations include the high cost of traceability technologies and the absence of standardised identification codes, which implies the need to re-label raw materials and pharmaceutical specialities prior to the preparation process. Hazardous sterile preparations were not included in this system because there is no single working system in the preparation area.

In conclusion, we highlight that the complete traceability of the preparation process ensures an extremely high level of safety, thereby meeting the established quality standards for the preparation of medicines in Spanish hospital pharmacy services.

Contribution to the scientific literatureThe results and conclusions of this study may serve as a valuable starting point for other pharmacy services wishing to implement a traceability and safe drug preparation system in a clean room.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe corresponding author declares that all authors have consented to the submission and publication of the article submitted for review.

The article is original, has not been previously published, and has not been simultaneously submitted for review by any other journal.

The article does not include unpublished material copied from other authors without their consent.

FundingNone declared.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMarta Echávarri de Miguel: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Belén Riva de la Hoz: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Margarita Cuervas-Mons Vendrell: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Beatriz Leal Pino: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision. Luis Fernandez Romero: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision.

Noe González Rodríguez, co-founder and manager at Basesoft.