To determine the perception of patients and practitioners regarding the role of the hospital pharmacist along the care continuum.

MethodThis was a multicenter cross-sectional observational analytical study, carried out in two phases between 15 October and 31 December 2020. In the first phase, a literature search was carried out to identify specific questionnaires that measured the overall satisfaction of patients in relation to the work of hospital pharmacists. Subsequently, a specific consensus-based questionnaire was developed, structured into three areas: care, relationships, and capacity-building and training. The study included patients treated in the participating centers and served by patient associations. They had to be older than 18 years, present with a chronic condition, and be treated with medication for hospital use. In the second phase, a qualitative study was carried out using focus group discussions to analyze how hospital pharmacists are perceived and how they would like to be recognized by patients. Four meetings were held in different territories of Spain. Previously, the research team agreed on the questions to be asked, which were grouped into four sections: healthcare, relational, training and information.

ResultsA total of 482 surveys were obtained. The percentage of patients who expressed a positive view of the role of the hospital pharmacist was 88.0% (n = 424). In the multivariate analysis, the most positive opinions about these professionals were expressed by women and by patients who had received previous care in the hospital, those who had a high opinion of the coordination of these professionals with the rest of the care team, and those who had received the greatest amount of emotional support. Integration of the pharmacist with the healthcare team was found to vary across different hospitals and the hospitals’ public image we seen to be related to the way they were pharmacoeconomically managed. In the sections related to capacity-building and training and challenges for the future, respondents emphasized the need to promote the introduction of new patient monitoring technologies.

ConclusionsPatients have a good opinion of the service provided by hospital pharmacists, although many are unaware of the significance of their role.

Determinar la percepción de los pacientes y profesionales respecto al papel del farmacéutico de hospital en el proceso asistencial sanitario.

MétodoEstudio multicéntrico, observacional, analítico y transversal, realizado en dos fases entre el 15 de octubre y el 31 de diciembre de 2020. En la primera fase se realizó una búsqueda bibliográfica para identificar cuestionarios específicos que midieran la satisfacción global de los pacientes en relación con la actividad asistencial de los farmacéuticos de hospital. Al no identificarse ninguno validado y adaptado, se elaboró un cuestionario específico. Se estructuró en tres áreas: asistencial, relacional y de capacitación y formación. Se incluyeron pacientes atendidos en los centros participantes y asociaciones de pacientes colaboradoras en el proyecto, mayores de 18 años, con patología crónica y tratamiento con medicación de uso hospitalario. En la segunda fase se llevó a cabo un estudio cualitativo en formato focus group para analizar cómo son percibidos y cómo les gustaría ser reconocidos a los farmacéuticos de hospital por parte de los pacientes. Se realizaron cuatro reuniones en diferentes territorios de España. Previamente el equipo investigador acordó el guion y las preguntas a llevar a cabo, incluyéndose 13, agrupadas por bloques: asistencial, relacional, formación e información.

ResultadosSSe obtuvieron un total de 482 encuestas. El porcentaje de pacientes que valoraron positivamente el papel del farmacéutico de hospital fue del 88,0% (n = 424). Se identificó que tienen mejor opinión sobre los farmacéuticos hospitalarios las mujeres, los pacientes que habían recibido atención previa en el hospital, los que valoraron mejor la coordinación de estos profesionales con el resto del equipo y aquellos con mayor apoyo emocional previo recibido. En la segunda fase se identificó que la integración del farmacéutico con el equipo varía en función de los centros y que la imagen que se tiene es la relacionada con la gestión farmacoeconómica. En el bloque de capacitación y formación, así como retos de futuro, se identificó la necesidad de fomentar la introducción de nuevas tecnologías para el seguimiento de los pacientes.

ConclusionesLos pacientes tienen una buena opinión del servicio prestado por el farmacéutico de hospital, aunque muchos desconocen su papel.

The increased life expectancy that goes with the improvement of social conditions, and especially healthcare conditions, is leading to an ageing population1. An older average age is associated with larger numbers of patients suffering from chronic conditions. However, there are more and more patients who develop chronic conditions at earlier ages, mainly because of therapeutic advances that have made it possible for certain diseases that were untreatable in the past to be dealt with as chronic conditions today2. The greater complexity of care and higher consumption of resources that these conditions demand have necessitated a series of initiatives aimed at preserving the system's sustainability, leading to the design of stratification models, chronicity plans or personalized medicine strategies3,4. Patient management is thus evolving towards a greater clinical complexity, which demands multidisciplinary care in order to address chronification of diseases, pluripathology and polypharmacy5,6.

Furthermore, in recent years the role of patients with regard to their disease has changed, since they have shifted from the position of consumers of healthcare and social resources to that of individuals who are much more involved in the decision-making process surrounding their conditions. This situation generates a dynamic, two-way bond with healthcare professionals which contributes to the improvement of the patient's health. One of the reasons behind this change in the relationship between patients and caregivers is the social and technological evolution that has been brought about by modern Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and the development of social media. At the same time, patients’ rights movements are continually gaining strength, and the demands of patient associations have become increasingly important, relevant and influential in healthcare decision-making processes7.

The evolution of patient needs and expectations, of the health system as a whole and of the conditions of health professionals in particular, is driving the inevitable process of transformation that currently envelops the field of hospital pharmacy4,8,9. This emerges as a professional opportunity to reassess the role the health system wishes to play in the context of its care activities, to determine what potential gaps should be addressed in order to meet the expectations of the system and its stakeholders, and to define the challenges that must be overcome in the present scenario if such a goal is to be achieved with success. Different international societies and experts have singled out patient-focused professional guidance as the main lever for advancing the effort to meet the needs and expectations of the health system and its professionals10-13. As the improvement of healthcare has evolved, including the patient's perspective, there has been in recent years a growing interest in aspects having to do with the humanization of care. A reflection of this is the development of the respective plans that have been launched by the health authorities, aimed at large spaces of intervention (autonomous regions, hospitals14-16), or the more recent publication of the “Guide for the Humanization of Hospital Pharmacy Services” by the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH)17.

Although some studies have identified patient satisfaction or experience within certain healthcare environments of hospital pharmacy that reflect the above mentioned evolution, in recent years most of these papers refer to local or -at most- regional settings and focus on a single specific activity. There is thus a need to gain knowledge regarding the perception patients have of how this transformation of healthcare is impacting the delivery of care in the different professional settings in which hospital pharmacists (HP) do their work, with a view to taking whatever corrective measures may be required. Knowledge of the professional's point of view is also needed, in order to push the improvement process forward more appropriately.

The main aim of the present study was to evaluate the perception patients have of the role of the HP in the overall process of healthcare provision. The study's secondary aims were to learn the patients’ opinion of HPs in terms of the latter's specific performance of their healthcare duties and to analyze how HP professionals are perceived and would like to be recognized by the public.

MethodsA multicentric, observational, analytic and cross-sectional study carried out between 15 October and 31 December 2020.

To analyze the study's main goal, the literature was searched to identify specific questionnaires measuring patient perception of HP services or, as the case may be, the overall evaluation of patients regarding their interaction with HP services in healthcare. Since none that had been validated and adapted were identified, the study research team designed, by consensus, a specific questionnaire for the purpose. The questionnaire included 25 questions, of which 13 were designed for Likert-type answers, 8 were dichotomous (yes/no) and the rest were multiple-choice. The demographically characterized questionnaire was divided into three contextual areas: care, relational aspects and capacity building and training. The question regarding how patients valued the role of HPs within the healthcare provision process was determined to be the main variable of the study. Based on that main variable, bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed of all the variables relating to the patients’ opinion of HP performance.

Patients were drawn, consecutively, from those who had visited the hospital pharmacy departments of the four participating centers during the study period. They were all over 18 years of age, had chronic pathologies and were receiving treatment with hospital-grade medication. Additionally, during the same period, participants were recruited through 29 patient associations from all over Spain who had a collaboration agreement with the organizer of the study.

The variables collected in the questionnaire to assess the positive or negative perception of patients regarding the role of HPs covered demographics, clinical aspects, healthcare knowledge and abilities and relations between patients and HP departments.

To calculate the required sample size, the most favorable variability was ascribed to the primary objective (p = 0.5, q = 0.5, p x q = 0.25) with a confidence level of 95% (Z = 1.96), an error of 5% and losses of 20%. Using the qualitative variable formula for infinite populations, adjusted for finite populations with the expected losses, a sample size of 480 patients was determined. Patients were selected through convenience sampling. The sample universe was determined from the latest update of the SEFH 2020 White Paper on Hospital Pharmacy. The statistical analysis was carried out in accordance with the type of analyzed variable. Absolute and relative frequencies were calculated for the qualitative and median variables and the standard deviation was calculated for the quantitative variables. The chi-square test was used to analyze proportions and the Student's t-test was used to compare averages. A step-by-step binary logistic multivariate analysis was performed in order to minimize the confusion bias. The odds ratio was calculated with a 95% confidence limit. The area under the ROC curve was calculated with a confidence limit of 95% to assess the discriminatory power of the obtained model. A binary logistic regression multivariate analysis of all the factors considered in the study, in terms of whether the role of HPs was perceived as positive or not, was carried out to confirm the above points and ascertain what factors were of greatest importance. This was performed using forward stepwise selection, by adding variables until the best adjustment model was obtained.

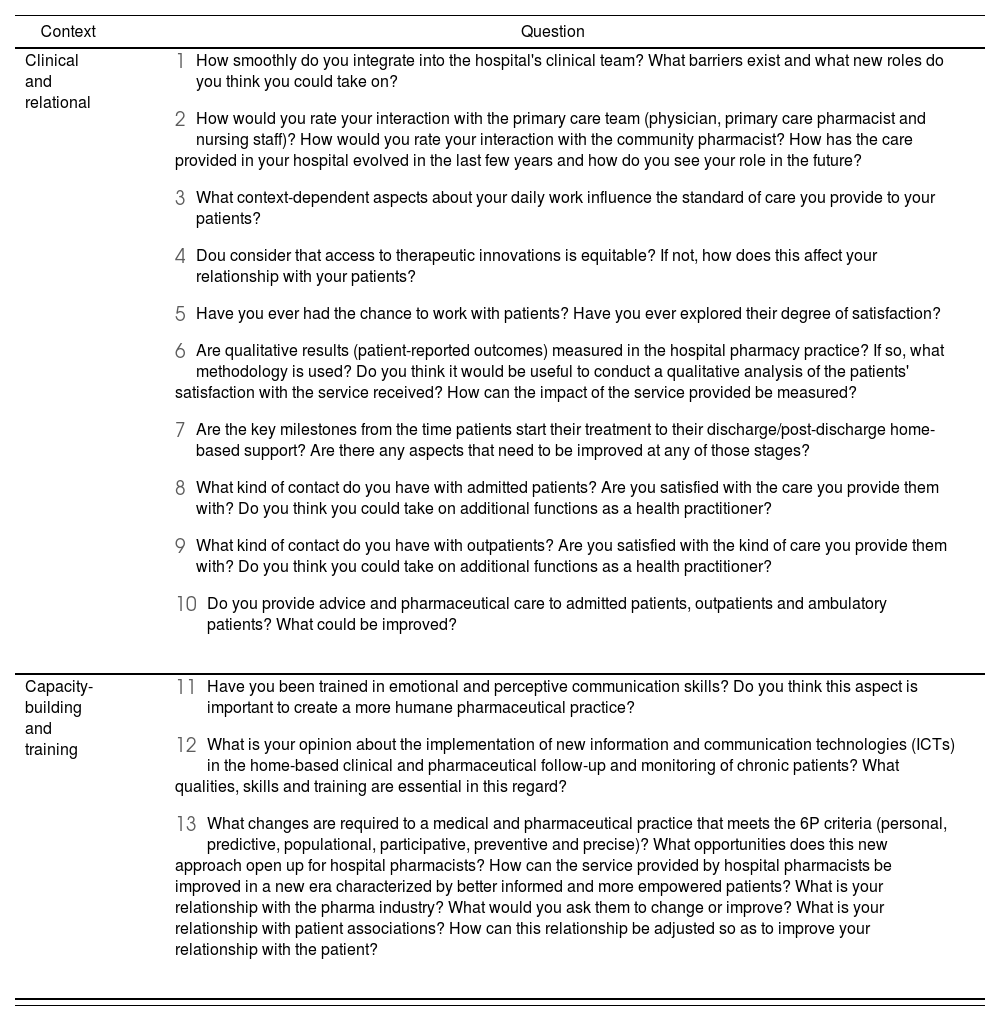

To respond to the study's secondary objectives of getting to know the patients’ opinion of HP performance and analyzing how HP professionals were perceived and would like to be recognized, qualitative data were collected. To this end, focus group sessions were organized in conjunction with HPs. Four sessions were held in different regions of Spain, in gatherings including a maximum of eight hospital pharmacy specialists, led by an expert in group discussion techniques who encouraged the lively exchange of opinions. The basic idea in these focus groups was for all participants to express their positions, ideas and thoughts about each of the points brought up for discussion. The project research team wrote the script and drew up 13 questions, not validated in advance, which were divided into sections, including: healthcare context; relational context; and training and information context (Table 1).

Questions asked at the focus group discussion with hospital pharmacy practitioners

| Context | Question |

|---|---|

| Clinical and relational |

|

| Capacity-building and training |

|

The study adhered to good practice standards. No identification details were included in the data collection notebook. The analysis, which was strictly anonymous and subject to encryption, required no informed consent procedure. Approvals for the study were secured from the Patient Chair Committee and the Ethical Committee of the University of Alicante (code UA-2020-11-18).

ResultsA total of 482 questionnaires were obtained. Of these, 336 came from patient associations and 146 came from patients treated at the participating hospitals. Most of the respondents were women (61%) with an average age of 50 (IQR: 59-41). The most frequent pathologies among the patients were: 24% arthritis; 18% HIV infection; 13% cancer. The rest, up to 16 different conditions, accounted for less than 5% each.

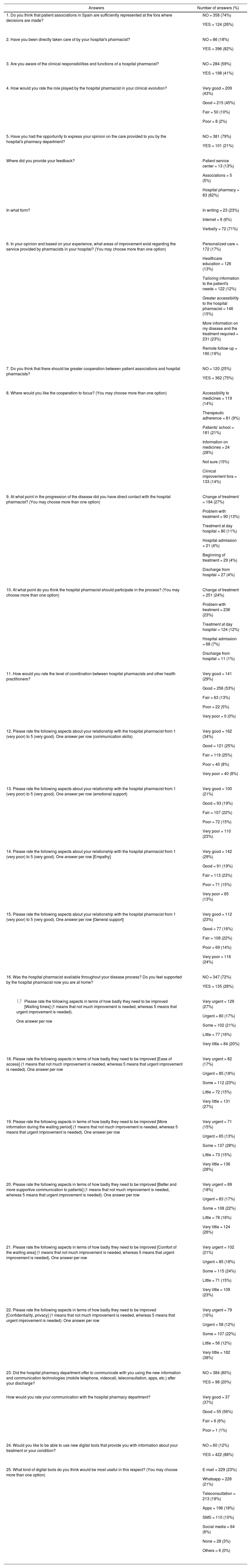

The answers, recorded for full questionnaires including every section (healthcare context, relational context and capacity-building and training context), are shown in table 2.

Answers to the survey administered to patients

| Answers | Number of answers (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. Do you think that patient associations in Spain are sufficiently represented at the fora where decisions are made? |

|

| 2. Have you been directly taken care of by your hospital's pharmacist? |

|

| 3. Are you aware of the clinical responsibilities and functions of a hospital pharmacist? |

|

| 4. How would you rate the role played by the hospital pharmacist in your clinical evolution? |

|

| 5. Have you had the opportunity to express your opinion on the care provided to you by the hospital's pharmacy department? |

|

| Where did you provide your feedback? |

|

| In what form? |

|

| 6. In your opinion and based on your experience, what areas of improvement exist regarding the service provided by pharmacists in your hospital? (You may choose more than one option) |

|

| 7. Do you think that there should be greater cooperation between patient associations and hospital pharmacists? |

|

| 8. Where would you like the cooperation to focus? (You may choose more than one option) |

|

| 9. At what point in the progression of the disease did you have direct contact with the hospital pharmacist? (You may choose more than one option) |

|

| 10. At what point do you think the hospital pharmacist should participate in the process? (You may choose more than one option) |

|

| 11. How would you rate the level of coordination between hospital pharmacists and other health practitioners? |

|

| 12. Please rate the following aspects about your relationship with the hospital pharmacist from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very good). One answer per row (communication skills) |

|

| 13. Please rate the following aspects about your relationship with the hospital pharmacist from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very good). One answer per row (emotional support) |

|

| 14. Please rate the following aspects about your relationship with the hospital pharmacist from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very good). One answer per row [Empathy] |

|

| 15. Please rate the following aspects about your relationship with the hospital pharmacist from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very good). One answer per row [General support] |

|

| 16. Was the hospital pharmacist available throughout your disease process? Do you feel supported by the hospital pharmacist now you are at home? |

|

|

|

| 18. Please rate the following aspects in terms of how badly they need to be improved [Ease of access] (1 means that not much improvement is needed, whereas 5 means that urgent improvement is needed). One answer per row |

|

| 19. Please rate the following aspects in terms of how badly they need to be improved [More information during the waiting period] (1 means that not much improvement is needed, whereas 5 means that urgent improvement is needed). One answer per row |

|

| 20. Please rate the following aspects in terms of how badly they need to be improved [Better and more supportive communication to patients] (1 means that not much improvement is needed, whereas 5 means that urgent improvement is needed). One answer per row |

|

| 21. Please rate the following aspects in terms of how badly they need to be improved [Comfort of the waiting area] (1 means that not much improvement is needed, whereas 5 means that urgent improvement is needed). One answer per row |

|

| 22. Please rate the following aspects in terms of how badly they need to be improved [Confidentiality, privacy] (1 means that not much improvement is needed, whereas 5 means that urgent improvement is needed). One answer per row |

|

| 23. Did the hospital pharmacy department offer to communicate with you using the new information and communication technologies (mobile telephone, videocall, teleconsultation, apps, etc.) after your discharge? |

|

| How would you rate your communication with the hospital pharmacy department? |

|

| 24. Would you like to be able to use new digital tools that provide you with information about your treatment or your condition? |

|

| 25. What kind of digital tools do you think would be most useful in this respect? (You may choose more than one option) |

|

In this regard, 88% (n = 424) of the patients had a positive perception of the pharmacist's role (“good” or “very good”), while 12% (rest of replies; n = 58) had a negative perception.

To the question regarding the degree of knowledge patients have about the HP's responsibilities, most respondents (59%) replied that they were not familiar with them, versus 41%, who said they were.

The relationship with the HP was good or very good in 59% of cases. Among aspects that could be improved, most respondents stated they would welcome greater emotional support, more empathy and better personal guidance throughout the treatment process.

Patients with a positive opinion of the role of HPs stated that they were adequately taken care of, although they thought there was room for improvement in terms of information, personal care, outpatient follow-up, accessibility, health education and general cooperation. They also demanded greater collaboration from patient associations with regard to schools for patients, joint discussion forums, accessibility to medication and adherence to treatment, among other highlighted issues.

For patients the best time to interact with the HP was at the beginning of treatment, followed by times when changes in medication were required or treatment issues arose.

Additionally, patients valued the possibility of using ITC tools very highly, but stated they had only been offered them 20% of the time.

In spite of their good opinion about the coordination between the HP and other healthcare professionals, patients thought it would be desirable to improve communication, emotional support, empathy and personal guidance. They also demanded improvements in waiting times, ease of access, comfort and confidentiality and information.

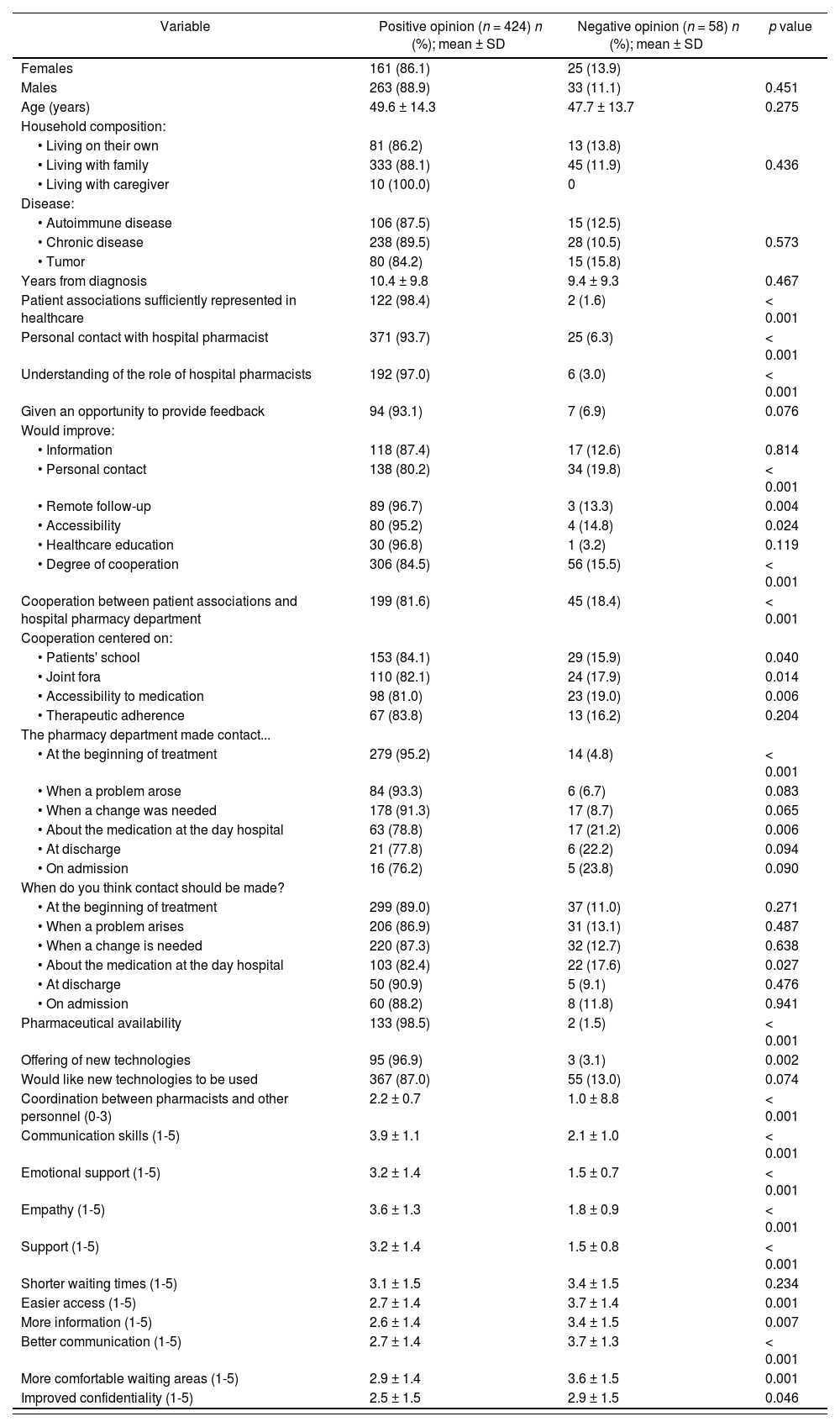

Table 3 shows the variables included in the bivariate and logistic regression model applied to the factors associated with positive or negative opinions of the HP's role.

Bivariate analysis of the variables related to the patients' opinion on hospital pharmacists

| Variable | Positive opinion (n = 424) n (%); mean ± SD | Negative opinion (n = 58) n (%); mean ± SD | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 161 (86.1) | 25 (13.9) | |

| Males | 263 (88.9) | 33 (11.1) | 0.451 |

| Age (years) | 49.6 ± 14.3 | 47.7 ± 13.7 | 0.275 |

| Household composition: | |||

| • Living on their own | 81 (86.2) | 13 (13.8) | |

| • Living with family | 333 (88.1) | 45 (11.9) | 0.436 |

| • Living with caregiver | 10 (100.0) | 0 | |

| Disease: | |||

| • Autoimmune disease | 106 (87.5) | 15 (12.5) | |

| • Chronic disease | 238 (89.5) | 28 (10.5) | 0.573 |

| • Tumor | 80 (84.2) | 15 (15.8) | |

| Years from diagnosis | 10.4 ± 9.8 | 9.4 ± 9.3 | 0.467 |

| Patient associations sufficiently represented in healthcare | 122 (98.4) | 2 (1.6) | < 0.001 |

| Personal contact with hospital pharmacist | 371 (93.7) | 25 (6.3) | < 0.001 |

| Understanding of the role of hospital pharmacists | 192 (97.0) | 6 (3.0) | < 0.001 |

| Given an opportunity to provide feedback | 94 (93.1) | 7 (6.9) | 0.076 |

| Would improve: | |||

| • Information | 118 (87.4) | 17 (12.6) | 0.814 |

| • Personal contact | 138 (80.2) | 34 (19.8) | < 0.001 |

| • Remote follow-up | 89 (96.7) | 3 (13.3) | 0.004 |

| • Accessibility | 80 (95.2) | 4 (14.8) | 0.024 |

| • Healthcare education | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | 0.119 |

| • Degree of cooperation | 306 (84.5) | 56 (15.5) | < 0.001 |

| Cooperation between patient associations and hospital pharmacy department | 199 (81.6) | 45 (18.4) | < 0.001 |

| Cooperation centered on: | |||

| • Patients' school | 153 (84.1) | 29 (15.9) | 0.040 |

| • Joint fora | 110 (82.1) | 24 (17.9) | 0.014 |

| • Accessibility to medication | 98 (81.0) | 23 (19.0) | 0.006 |

| • Therapeutic adherence | 67 (83.8) | 13 (16.2) | 0.204 |

| The pharmacy department made contact... | |||

| • At the beginning of treatment | 279 (95.2) | 14 (4.8) | < 0.001 |

| • When a problem arose | 84 (93.3) | 6 (6.7) | 0.083 |

| • When a change was needed | 178 (91.3) | 17 (8.7) | 0.065 |

| • About the medication at the day hospital | 63 (78.8) | 17 (21.2) | 0.006 |

| • At discharge | 21 (77.8) | 6 (22.2) | 0.094 |

| • On admission | 16 (76.2) | 5 (23.8) | 0.090 |

| When do you think contact should be made? | |||

| • At the beginning of treatment | 299 (89.0) | 37 (11.0) | 0.271 |

| • When a problem arises | 206 (86.9) | 31 (13.1) | 0.487 |

| • When a change is needed | 220 (87.3) | 32 (12.7) | 0.638 |

| • About the medication at the day hospital | 103 (82.4) | 22 (17.6) | 0.027 |

| • At discharge | 50 (90.9) | 5 (9.1) | 0.476 |

| • On admission | 60 (88.2) | 8 (11.8) | 0.941 |

| Pharmaceutical availability | 133 (98.5) | 2 (1.5) | < 0.001 |

| Offering of new technologies | 95 (96.9) | 3 (3.1) | 0.002 |

| Would like new technologies to be used | 367 (87.0) | 55 (13.0) | 0.074 |

| Coordination between pharmacists and other personnel (0-3) | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 8.8 | < 0.001 |

| Communication skills (1-5) | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| Emotional support (1-5) | 3.2 ± 1.4 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| Empathy (1-5) | 3.6 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| Support (1-5) | 3.2 ± 1.4 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

| Shorter waiting times (1-5) | 3.1 ± 1.5 | 3.4 ± 1.5 | 0.234 |

| Easier access (1-5) | 2.7 ± 1.4 | 3.7 ± 1.4 | 0.001 |

| More information (1-5) | 2.6 ± 1.4 | 3.4 ± 1.5 | 0.007 |

| Better communication (1-5) | 2.7 ± 1.4 | 3.7 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

| More comfortable waiting areas (1-5) | 2.9 ± 1.4 | 3.6 ± 1.5 | 0.001 |

| Improved confidentiality (1-5) | 2.5 ± 1.5 | 2.9 ± 1.5 | 0.046 |

SD: standard deviation.

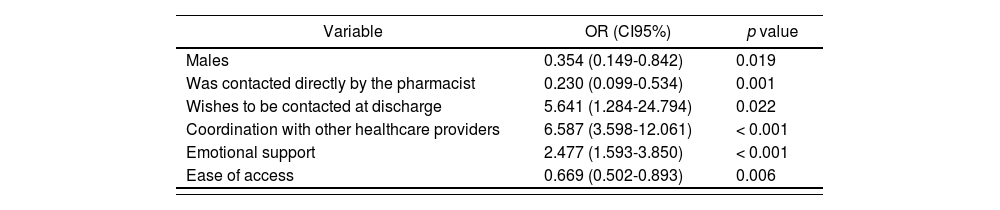

The multivariate analysis was completed with six variables and a model whose chi-square value was 176.926 (p < 0.001). Respondents who were most positive about the HP's role included the following groups: women (p = 0.019); patients who wished to have in-person interaction at the time of discharge (p = 0.022); patients who had received direct care from HP professionals at the hospital (p < 0.001); patients with a more positive opinion regarding coordination between the latter and the rest of the healthcare personnel (p < 0.001); patients who valued ease of access (p = 0.006); and patients who had received greater emotional support from the HP department (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Multivariate analysis on the opinion of patients about hospital pharmacists

| Variable | OR (CI95%) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Males | 0.354 (0.149-0.842) | 0.019 |

| Was contacted directly by the pharmacist | 0.230 (0.099-0.534) | 0.001 |

| Wishes to be contacted at discharge | 5.641 (1.284-24.794) | 0.022 |

| Coordination with other healthcare providers | 6.587 (3.598-12.061) | < 0.001 |

| Emotional support | 2.477 (1.593-3.850) | < 0.001 |

| Ease of access | 0.669 (0.502-0.893) | 0.006 |

CI: confidence interval; OR: odss ratio.

The model had a high specificity and a high sensitivity, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.947 (CI 95% 0.018-0.976; p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

The qualitative section of the study assessed the answers most frequently given by the pharmacists in the focus groups. Regarding the healthcare and relational contexts, the general opinion was that the HP's integration with the rest of the healthcare team varied from center to center. HPs were perceived mainly in their role as pharmaceutical and financial managers and their performance was viewed as highly bureaucratized. It was pointed out that interaction between HPs and primary care teams did not flow smoothly, and that communication with community pharmacists was very limited.

Different contextual aspects were identified as having an impact on the HP's daily tasks. These included the pressures of a growing healthcare demand, the need to tailor available resources to existing functions and performance, knowledge and information requirements regarding HP duties, the indispensable legal precautions that must be observed in the different treatment scenarios, the greater importance of personalized pharmaceutical care and the emergence of a different hospital pharmacy model with new roles and responsibilities which must be adapted to present and future contexts.

Furthermore, an exhaustive analysis of the patient's experience was deemed essential, but was not considered to be implemented consistently in all the different territories and centers.

It was observed that personal interaction between HPs and hospitalized and ambulatory patients was limited or even nonexistent in some healthcare territories, centers and districts. In general, HPs were not satisfied with the level of information they were given regarding their job description, their tasks and their duties. In the case of external patients, although certain schedules were in place, staff shortages made it difficult to provide adequate pharmaceutical care. Ambulatory patients were sometimes referred to HP departments or to nursing departments at random, and hospitalized patients were not always given pharmaceutical care as a matter of course. Considering the limited nature of resources, there was clearly room for improvement in terms of pharmaceutical care in all three populations (hospitalized patients, patients in ambulatory care and external patients). Longitudinality in patient follow-up and a greater emphasis on explaining treatments, resolving doubts and issues and facilitating proper and adequately persistent adherence to therapeutic protocols were identified as key improvement areas. Other aspects that were identified as requiring improvement included interaction between primary care and hospital departments and the use and application of ICTs.

Among the suggested new tasks and duties that HPs could take on as agents for health, the following were listed: more specifically clinical functions; guidance in all matters having to do with prescription drugs; and a more important role in the promotion and instilment of healthy habits. All this should be based on closer personal interaction with patients and a greater empathy and trust, which were deemed to result in better health outcomes.

Regarding the capacity-building and training area, a need was identified to promote, at university and through postgraduate studies, knowledge and skills associated with emotional and perceptive communication, which should at any rate be part of standard learning programs.

It was also considered indispensable to implement ICTs in the process of clinical and pharmaceutical follow-up and monitoring of remote patients, and especially those with chronic conditions. Furthermore, the sharing of communication systems between hospital pharmacy departments and other facilities was considered to be indispensable, since it was important to set up healthcare circuits that responded to identified needs, particularly as regards interoperability.

With reference to future challenges, it was deemed essential to give HPs greater visibility and weight, to increase the levels of specialization and training in cross-sectional fields of expertise, and to further develop the concept of excellence in all services rendered, through greater personalization of care and the provision of adequate resources, of different kinds, to cover every different circumstance.

Finally, as regards relations between HPs and patient associations, it was considered important for either party to be familiar with the other's needs and concerns through the improvement of mutual communication and the development of joint projects and initiatives.

DiscussionThe present study has revealed that patients have a good or very good opinion of the services provided by HPs in healthcare, although a significant percentage of them are unaware of the HP's exact role. However, there are aspects that patients would like to see improved: information, personalized care, distance follow-up, accessibility, health education, and general cooperation. On the other hand, professionals seem to perceive their own activity as too weighted down by bureaucratic and pharmacoeconomic considerations. They would like their work to be more clinically orientated, and to have the resources they need to perform their duties more adequately, in closer proximity to patients at all levels of the healthcare system (hospitalization, outpatient care and external care). Both patients and professionals consider that the deployment and use of ICTs are indispensable in order to guarantee the continuity and longitudinality of patient follow-up and care.

As can be seen from the multivariate analysis, the variables that predict a more positive opinion of the HP's activity are related to aspects identifying prior personal interaction and direct contact with patients. In other words, once the patients become aware of the professional's activity they value the HP's role within the healthcare system very positively.

The present study signals the need to establish a new healthcare model and bring about a new relational approach regarding interaction with patients. Much of what is here expressed, however, reflects the strategic lines of action for the advancement of the pharmaceutical profession that have been traced by international scientific societies in the last few years18-20 and in recent research, which has expressly pointed out the benefits of such a new healthcare model both in general terms and with regard to specific types of patients21-24.

Nonetheless, one of the key aspects of this study is that it highlights the fact that a significant percentage of patients are unaware of the duties and responsibilities of HPs. Bridging that gap is essential in order to improve all other areas: if patients are not familiar with the value and the key role of hospital pharmacists in all matters having to do with their pharmacological therapies, they will not be in a position to demand the HP's services, nor will they clearly understand the latter's role and how to make the most of it.

In this respect it becomes clear that pharmacy departments could develop closer ties with patient associations. Initiatives based on the design of information tools regarding drugs, collaborative training activities such as patient schools or discussion groups or the co-creation of technological solutions are some of the initial possibilities that could currently be explored, modelled on positive experiences of the present and the recent past25-28.

Another element that could contribute significantly to improving healthcare models would be to make HPs more available and accessible to patients, and to introduce strategies aimed at building the former's capacities in emotional and perceptive communication. This aspect, one of the most highly valued by the participants in the study, would create a better experience for the patient. To further this goal, patients and professionals both agreed on the fundamental importance of incorporating new technologies into pharmaceutical practice. The COVID-19 pandemic has in this respect catalyzed the development and implementation of telepharmacy, which covers within its sphere of action many of the demands voiced by patients: pharmacological and therapeutic follow-up, information and training, coordination of care and informed delivery of medication, under permanent guidance and in conditions of remote pharmaceutical practice29.

Patients and professionals are equally committed to a model of care that is based on planning, integrating and sharing, throughout the different levels of the healthcare system, and is conducive to improving the health outcomes and the experience of patients. Given the latter's new role and the need to work jointly with patient associations, there is a particular need to measure and refine new concepts based on patient experience30. A detailed analysis that identifies each and every one of the stages of the patient's interaction with the hospital pharmacy department is of fundamental importance, since in no other way is it possible to gain knowledge of the key areas that require improvement in terms of excellence of service and provided care. In this respect, for example, changes in medication are perceived by patients as very important instances in their therapeutic experience. Although gaps have been identified and defined in so-called external care, improvements during hospitalization or at the time of discharge are somewhat more demanded by patients at this time.

In view of these findings, HPs could perhaps take the initiative and begin to lay the groundwork for resolving the proposed demands. The recently published new definition of pharmaceutical care19 stresses all these issues and favors a working strategy that is not only multidisciplinary but also, and especially, multidimensional in its approach to patients. It is essential to define the parameters and indicators that determine excellence in care, and to that end the common denominator lies in transformational leadership, based on communication, social responsibility and reputational impact at all levels. It would be equally advisable to introduce the concept of “patient experience” and further educate the community of patients, making regular use of questionnaires that are drawn up and validated with the help of experts. Departments of HP would thus be able to assess their results and introduce whatever improvements were required in specific aspects of their process of care.

The present conclusions must nonetheless be considered with caution, since the study, mainly due to its design, has several limitations. Firstly, given its cross-sectional nature, it cannot establish relationships of cause and effect. Neither was a cohort available for comparison of the analyzed data. Other limitations include a measurement bias -since the questions were not validated- and a selection bias, given the fact that sampling was performed using the convenience method, and not at random. However, these biases are accepted in studies based on qualitative designs. A detailed multivariate analysis was carried out to minimize the confusion bias. Additionally, the study included a limited number of professionals, who accounted for a very small percentage of the total population of active HPs in Spain. Nonetheless, the autonomous regions and hospitals that were chosen to take part in the study had the highest percentages of pharmacists in the country and were governed by rules and regulations that are representative of the current situation in Spain.

Research projects carried out over the next few years will reveal, by performing regular surveys with the aid of the same methodology and tools described in the present study, whether the introduction of the proposed areas for improvement has had a true impact on the overall perceptions of patients. There is even the possibility of contrasting the opinion of these hospital pharmacy professionals with the views of other members of the healthcare team, in order to identify potential shifts that have taken place and assess the level of visibility that has been achieved.

In conclusion, patients have a good opinion of the role of HPs. However, patients and professionals have both identified areas where progress is required in order to improve patient experience and collaboration and afford greater visibility to the care provided by HPs.

FundingNo funding.

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to thank all the participating patient associations as well as the hospital pharmacists who participated in the focus group discussions.

Conflict of interestNo conflict of interests.

Contribution to the scientific literature

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study devoted to analyzing the perception of patients with respect to the role played by hospital pharmacists in their care process. Although patients are in general highly appreciative of the service provided by pharmacists, many of them are not fully aware of the contribution made by those professionals. Despite their positive opinion, patients believe that some aspects of pharmaceutical services could be improved and ask for greater cooperation.

Moreover, the study also presents the point of view of hospital pharmacists themselves, who consider it necessary for their job to have a greater clinical component and to be provided with enough resources to accompany patients across the different areas of care (in-hospital, ambulatory and outpatient care).

Both patients and hospital pharmacists consider the incorporation and use of new technologies indispensable for a more continuous and longitudinal follow-up of the care provided.

Early Access date (09/08/2021).