We aimed to develop of a risk stratification model for the pharmaceutical care of patients with solid or hematologic neoplasms who required antineoplastic agents or supportive treatments.

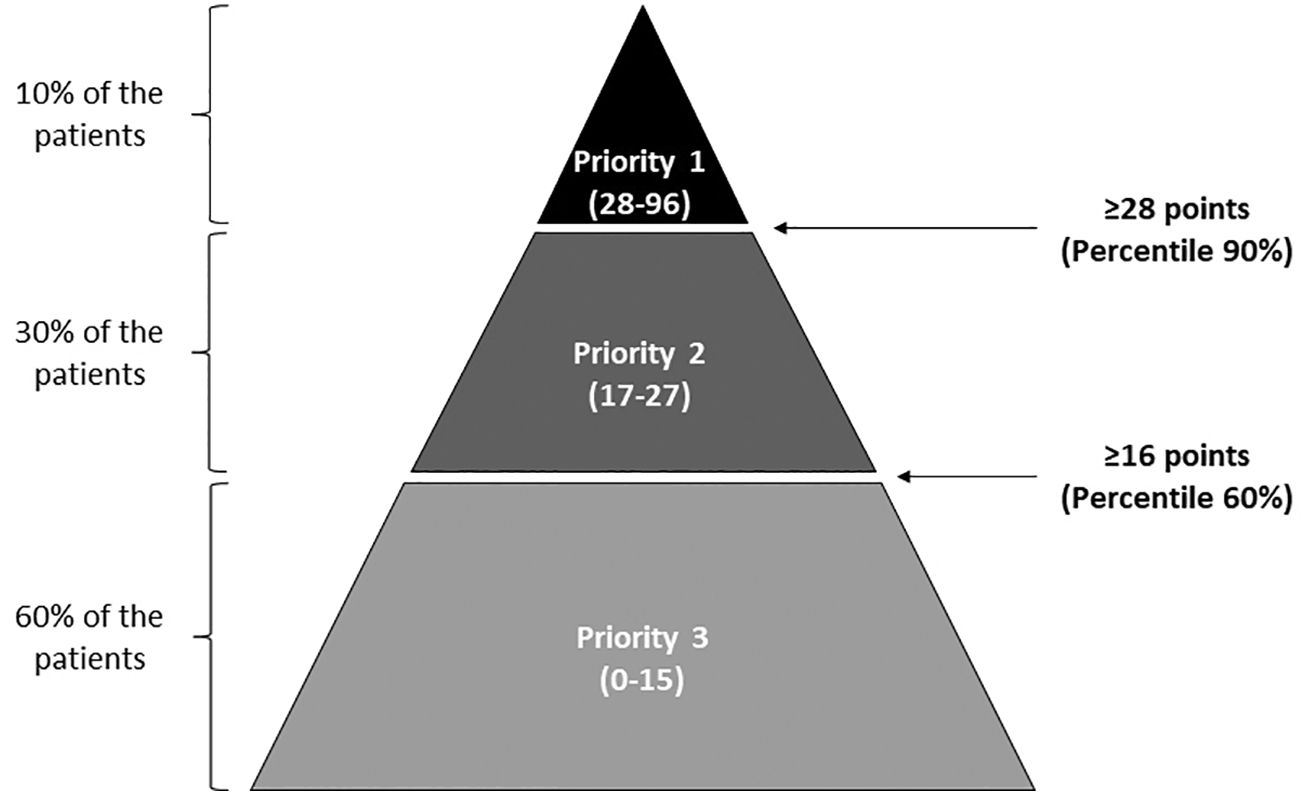

MethodThe risk stratification model was collaboratively developed by oncology pharmacists from the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH). It underwent refinement through 3 workshops and a pilot study. Variables were defined, grouped into 4 dimensions, and assigned relative weights. The pilot study collected and analyzed data from participating centers to determine priority levels and evaluate variable contributions. The study followed the Kaiser Permanente pyramid model, categorizing patients into 3 priority levels: Priority 1 (intensive PC, 90th percentile), Priority 2 (60th-90th percentiles), and Priority 3 (60th percentile). Cut-off points were determined based on this stratification. Participating centers recorded variables in an Excel sheet, calculating mean weight scores for each priority level and the total risk score.

ResultsThe participants agreed to complete a questionnaire that comprised 22 variables grouped into 4 dimensions: demographic (maximum score=11); social and health variables and cognitive and functional status (maximum=19); clinical and health services utilization (maximum=25); and treatment-related (maximum=41). From the results of applying the model to the 199 patients enrolled, the cut-off points for categorization were 28 or more points for priority 1, 16–27 points for priority 2, and less than 16 for priority 3; more than 80% of the total score was based on the dimensions of “clinical and health services utilization” and “treatment-related.” Interventions based on the pharmaceutical care model were recommended for patients with solid or hematological neoplasms, according to their prioritization level.

ConclusionThis stratification model enables the identification of cancer patients requiring a higher level of pharmaceutical care and facilitates the adjustment of care capacity. Validation of the model in a representative population is necessary to establish its effectiveness.

Desarrollar un modelo de estratificación de riesgo para la atención farmacéutica de pacientes con tumores sólidos o hematológicos que requieran agentes antineoplásicos o tratamientos de soporte.

MétodoEl modelo de estratificación de riesgo fue desarrollado de forma colaborativa por farmacéuticos oncológicos de la Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria (SEFH). Se realizó mediante tres talleres y un estudio piloto. Se definieron las variables, se agruparon en cuatro dimensiones y se asignaron pesos relativos. El estudio piloto recogió y analizó datos de los centros participantes para determinar los niveles de prioridad y evaluar las contribuciones de las variables. El estudio siguió el modelo piramidal de Kaiser Permanente, clasificando a los pacientes en tres niveles de prioridad: Prioridad 1 (percentil 90), Prioridad 2 (percentiles 60-90) y Prioridad 3 (percentil 60). Los puntos de corte se determinaron en función de esta estratificación. Los centros participantes registraron las variables en una hoja de Excel, calculando las puntuaciones medias de peso para cada nivel de prioridad y la puntuación total de riesgo.

ResultadosLos participantes accedieron a cumplimentar un cuestionario que comprendía 22 variables agrupadas en 4 dimensiones: demográfica (puntuación máxima =11); variables sociosanitarias y estado cognitivo y funcional (máximo=19); clínica y utilización de servicios sanitarios (máximo=25); y relacionada con el tratamiento (máximo=41). A partir de los resultados de la aplicación del modelo a los 199 pacientes reclutados, los puntos de corte para la categorización fueron 28 o más puntos para la prioridad 1, de 16 a 27 puntos para la prioridad 2 y menos de 16 para la prioridad 3; más del 80% de la puntuación total se basó en las dimensiones de "utilización de servicios clínicos y sanitarios" y "relacionada con el tratamiento". Se recomendaron intervenciones basadas en el modelo AF para pacientes con neoplasias sólidas o hematológicas, según su nivel de priorización.

ConclusiónEste modelo de estratificación permite identificar a los pacientes oncológicos que requieren un mayor nivel de atención farmacéutica y favorece el ajuste de la capacidad asistencial. Es necesaria la validación del modelo en una población representativa para establecer su efectividad.

Cancer is associated with a large and increasing burden due to its growing incidence, improved survival, and rapid availability of new treatments such as targeted molecules and immunological and cellular therapies, which make its management increasingly complex.1 As with other chronic conditions, this increasing burden together with the constraints in human and economic resources has led to a change in the way healthcare is delivered, from fragmented health services to integrated care.2 This integrated care will improve health outcomes and the effectiveness and sustainability of the heathcare systems.2

Integrated care may be defined as an approach to strengthen people-centered health systems through the promotion of the comprehensive delivery of quality services across the life-course, designed according to the multidimensional needs of the population and the individual and delivered by a coordinated multidisciplinary team of providers working across settings and levels of care.3 The oncology pharmacists are an essential part of the multidisciplinary team involved in all aspects of the care of patients with cancer.4 The evidence has shown that the oncology pharmacist benefits patients in terms of clinical care, by improving adherence to supportive care, reducing medication-related problems and lowering risk of drug-related morbidity.5 Oncology pharmacists also benefit patients by offering patient education, increasing use of information technology, and saving costs.5 In addition to their traditional roles6 in Spain are responsible for preparing parenteral antineoplastic drugs, dispensing targeted molecules for the treatment of cancer, and providing most oral antineoplastics and supportive treatments.

Among the integrated care models, the Kaiser Permanente model represents a population-based model and consists of the stratification of the population and delivery of services depending on the patients’ needs.7 Within this context and with the aim of improving the pharmaceutical care (PC) of chronically ill patients, the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH by its Spanish acronym) in 2012 published the “Strategic Plan of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy about the PC to the Chronic Patient”8 and established 6 main action lines, including the “Patient-Centered Approach: Stratification as a tool of the new care model” as the essential means of improving PC. In 2014, the SEFH established the Strategic Map for PC of Outpatients (MAPEX by its Spanish acronym) with the objective of “contributing to the improvement of the patient's health from the dispensing and/or pharmacotherapeutic follow-up through PC that adds value to the healthcare process and that promotes/allows the effective, safe use and efficient use of medicines in a framework of a continuous and comprehensive care.”9 These initiatives have led to the development by the SEFH of risk stratification model (SM) for specific pathologies, such as the risk SM for Pediatric Chronic Patients10 and for the PC of HIV patients.11

The stratification of patients with solid or hematological neoplasms was established as one of the strategic initiatives within the MAPEX strategic map for improving PC in the context of an increasing number of patients and the complexity of their treatments.

We present the pilot study with the objective of the development of a risk SM for the PC of patients with solid or hematologic neoplasms who require antineoplastic agents or supportive treatments. We aim to identify the patients who require the highest level of PC to optimize their cancer treatment. The level of PC offered should be proportionate to the needs of each patient.

MethodsThe risk SM was developed with the participation of a working group made up of 7 oncology pharmacists from centers all over Spain with experience in pharmaceutical care of cancer patients, most of whom are Board Certified Oncology Pharmacist® members of the Spanish Group of Oncology and Hematology Pharmacy (GEDEFO by its Spanish acronym), and a working group of the SEFH.

The risk SM was developed over a period of about a year, through 3 face-to-face workshops and fieldwork, our pilot study.

The first workshop took place in June 2017 and was devoted to defining the variables to be included in the risk SM based on those included in previous SEFH models. The variables were grouped into 4 dimensions: demographics, social and health variables and cognitive and functional status, clinical and health services utilization variables, and medication-related variables. Each variable was assigned a relative weight to measure the risk based on the expert opinion of the participants. The weight was scored from 1 to 4 depending on the relevance estimated for evaluating the global risk of the patient, with greater scores indicating greater relevance.

The fieldwork, which we have called the pilot study, served as the basis for the final redefinition of the model that was established at the second workshop in April 2018. Each of the variables, their impact and outcome was discussed. Adding clarifications favoring its application in the care field. All decisions were taken by unanimous vote.

The third workshop was held in May 2018 to define the actions of the PC model for outpatients with solid or hematological malignancies according to the 3 levels of prioritization and the design of the validation study. Actions in line with the other SEFH models involve a much more comprehensive level of PC with a high level of care coordination for patients at risk level 1.

The pilot study is the core of this work, and the experimental part of the development of this model.

Between November 2017 and February 2018, this research study was conducted with the aim of following the Kaiser Permanente pyramid model, establishing 3 levels of priority: Priority 1, i.e., patients requiring more intensive PC, including patients in the 90th percentile; Priority 2, patients between the 60th and 90th percentiles; and Priority 3, patients in the 60th percentile; cut-off points were established based on this stratification. Participating centers recorded information on the variables included in the model using an MS Excel sheet. Mean weight scores were obtained for each priority level for the total score of the risk SM as well as for the scores of the 4 dimensions of the model. Excluding the variable from the model and assessing the impact of exclusion on the number of patients who would change priority level analyzed the contribution of each variable to the SM.

Our non-interventional observational study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova (Lleida, Spain) and by the Spanish Medicines Agency as an observational, non-post-marketing study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the pilot study.

As there are no previous literature references to determine a sample of patients on a total population basis for a given safety and potency, to estimate the sample size for the validation study, the number of oncology and oncohematology patients seen in hospital pharmacy consultations was considered. The GEDEFO group estimated 1769 patients per year per hospital based on a survey12 conducted in 2016 in 95 centers, totaling 168 055 patients per year. With a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence level, the minimum sample size for the validation study should be 664 patients.

This pilot study was conducted as an interim study to determine potential futility. Including at least 10% of the estimated total number of patients was deemed sufficient. Ultimately, with the participation of 7 hospitals, the analysis was performed with 25% of the estimated total.

ResultsThe initial risk SMThe participants agreed to complete a questionnaire that comprised 22 variables. The demographic variables were age, weight, and pregnancy status and had a maximum score of 11. The social and health variables concerned cognitive and functional status and asked about unhealthy lifestyle habits, healthcare professional–patient relationships, mental disorders, cognitive impairment, and functional dependency (e.g., information on patient’s mental health history and psychiatric symptoms, evaluated by tools such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] distress thermometer, and the ECOG performance status), and the availability of social support and/or socioeconomic status, which had a maximum score of 19 points; the clinical and health services utilization variables included pluripathology/comorbidities, analytical variables, or other parameters that could have an impact on dosage adjustment, pain with poor pain control, hospitalization or visits to the emergency department in the previous month, swallowing difficulties, and number of antineoplastic treatment lines, which had a maximum score of 25. The treatment-related variables included polypharmacy, changes in the route of administration/pharmaceutical form/to a generic or biosimilar, modifications of the regular medication regimen, medication risk, complexity of the dose regimen, interactions, treatment-associated toxicity, treatment adherence, and treatment under special conditions (e.g., with a maximum score of 44). After the second meeting, it was decided that pediatric patients, patients who are pregnant, or patients with social or economic conditions that do not allow him or her to carry out the treatment properly should be categorized as priority 1, regardless of the total score in the tool. The details of the questions and criteria for scoring each variable are shown in Table 1.

Variables and relative weights of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH) Stratification Model for patients with solid or hematologic malignancies.

| Variable scope | Variable | Definition | Weighta | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLOCK 1. Demographic variables | Age | Pediatric patient (0–18 years)b | 4 | ||

| Weight: Nutritional risk | Determination of the patient's percentage of weight loss: Patient has unintentional weight loss >5% in the last 3 months.* For information purposes, the patient's current weight and the weight 3 months ago will be recorded. The tool automatically calculates the weight loss %. | 3 | |||

| Pregnant patientb | 4 | ||||

| Maximum block 1 score | 11 points | ||||

| BLOCK 2. Socio-health variables and cognitive and functional status | Unhealthy lifestyle | Drug and/or alcohol use >17 SD/week in women and >28 SD/week in men | 3 | ||

| Factors related to the patient–healthcare professional relationship | Patient with cultural and/or communication barriers | 2 | |||

| Mental disorders, cognitive impairment, and functional dependency | Patient with psychiatric history, including depression | 2 | |||

| Patient with symptoms of anxiety, depression, and/or psychological distress (sadness, worry, and anguish)c: | |||||

| HADS Questionnaire*For information purposes, the HADS questionnaire score will be recorded. | Questionnaire score ≥15. Depression (even items) or anxiety (odd items) scores >10. | 3 | |||

| Questionnaire score ≥15. Depression (even items) or anxiety (odd items) scores <10. | 2 | ||||

| NCCN Distress VAS*For information purposes, the Distress VAS score will be recorded. | Distress VAS=7–10 | 3 | |||

| Distress VAS=5–6 | 2 | ||||

| Cognitive impairment: In case of suspected difficulty in comprehension, determination of cognitive impairment will be determined by the Pfeiffer Index (Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire).*For information purposes, the Pfeiffer Index score will be recorded. | The patient can read and write | Questionnaire errors ≥3 | 2 | ||

| The patient cannot read and write | Questionnaire errors ≥4 | 2 | |||

| Functional dependency: ECOG-PS *For information purposes, the ECOG-PS score will be recorded. | ECOG-PS=3 | 3 | |||

| ECOG-PS=2 | 2 | ||||

| Social support and socioeconomic conditions | Patient without social support and or with socioeconomic conditions that do not allow him or her to carry out the treatment properly.b | 4 | |||

| Maximum block 2 score | 19 points | ||||

| BLOCK 3. Clinical and health services utilization variables | Pluripathology/comorbidities | The patient has 2 or more chronic diseases (excluding malignancies). | 4 | ||

| Analytical variables and other parameters that have an impact on dose adjustment | The patient has altered analytical variables and other parameters that affect the dose adjustment. E.g.: Hepatic alterations, renal alterations, FEV1, and drug-associated toxicities. | 4 | |||

| Patient with poor pain control | Determination of pain intensity by means of the VAS scale. Poor control defined by Pain VAS score ≥7.*For information purposes, the Pain VAS score will be recorded. | 4 | |||

| No. hospitalizations and emergency room visits | Patient has had at least 1 admission/visit to the ED in the last month | 1 | |||

| Swallowing difficulty | The patient presents swallowing difficulties | 4 | |||

| Treatment lines | First course of treatmentb or change of treatment | 4 | |||

| Third or subsequent line of treatment | 4 | ||||

| Maximum block 3 score | 25 points | ||||

| BLOCK 4. Treatment-related variables | Polypharmacy | The patient takes 6 or more medications (home treatment), understanding as medication the pharmaceutical form accompanied by dosage and route (excluding treatment that is part of the oncological process). | 3 | ||

| Change of route of administration or pharmaceutical form, switching to a generic or biosimilar | 1 | ||||

| Modification of the regular medication regimen | The patient, due to his or her clinical situation, has required an adjustment or delay of doses of antineoplastic medication in the last 2 months. | 4 | |||

| Medication risk | In addition to the antineoplastic treatment, the patient takes any other high-alert drug (included in the Spanish ISMP list of high-alert drugs in chronic patients and/or in the American ISMP list of high-alert ambulatory drugs). | 3 | |||

| The patient takes medications with special storage/conservation conditions (e.g., medications that require a certain temperature, protection from light, humidity conditions, etc.). | 1 | ||||

| Complexity of the dosing regimen | The patient takes an oral antineoplastic drug (excluding supportive care) on a discontinuous schedule. E.g.: capecitabine, sunitinib. | 2 | |||

| Patient takes 2 or more oral antineoplastic drugs (excluding supportive care) with discontinuous schedules and/or different administration schedules. E.g.: lapatinib+capecitabine; MPV, KRD; Lena+Dexa; palbociclib+letrozole; palbociclib+fulvestrant; abiraterone+prednisone. | 4 | ||||

| InteractionsThe Lexicomp or Medinteract database will be used. | CAM Interactions Consultation (Complementary and Alternative Medicine) | 3 | |||

| Initiation of oncological treatment with complex pharmacokinetic profile | 3 | ||||

| Level C interactions | 3 | ||||

| Level D or X interactions | 4 | ||||

| Treatment-associated toxicity | The patient has presented/presents grade ≥2 treatment-associated toxicity in the last 3 cycles.Assessment of toxicity using the American National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC) Scale (WHO). | 4 | |||

| Adherence to treatment | If there is suspicion or evidence that the patient is not adherent to his or her oncological treatment, determination of adherence by 2 indirect validation methods: computerized dispensing records+Morinsky-Green-Levine Questionnaire. | Non-adherent patient: dispensing record ≤90% and in questionnaire does not answer any of the 4 questions correctly. | 4 | ||

| Treatment under special conditions | Patient in clinical trial | 4 | |||

| Patient with special use treatment | 3 | ||||

| Patient with recently marketed treatment (first year of authorization) | 2 | ||||

| Maximum block 4 score | 41 points | ||||

HADS, Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale; ISPM, Institute for Safe Medication Practices; SEFH, Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (“Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria”); VAS, visual analog scale.

Note: The tool is also available for the member of the SEFH at: https://www.sefh.es/mapex/documentacion.php.

Patients who score in these items are categorized as priority 1 regardless the total score in the tool.

In case of suspected patient with symptoms of anxiety, depression, and/or psychological distress (sadness, worry, and panic), only 1 of the 2 questionnaires (HADS or Distress VAS) will be completed. In the case of completing both questionnaires, the score obtained in the HADS questionnaire will be taken into account.

Pilot study: Risk stratification pyramid and contribution of the variables to the risk prioritization levels

The 7 participant sites included 199 patients whose characteristics are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Most patients were over age 50 and were evenly distributed regarding sex; the most common malignancies were colorectal cancer (n=44, 22.0%), breast cancer (n=33, 16.5%), lung cancer (n=20, 10.0%), prostate cancer (n=13, 6.5%), and multiple myeloma (n=10, 5.0%). Of the 199 patients, 18 were categorized as priority 1, 59 as priority 2, and 122 as priority 3. The resultant cut-off points for that categorization were 28 or more points for priority 1, between 16 and 27 points for priority 2, and less than 16 points for priority 3 (Fig. 1). The mean total score and mean scores of the 4 dimensions of the tool for the total sample are presented in Fig. 2; over 80% of the risk total score was based on the dimensions of “clinical and health services utilization” and “treatment-related variables” (Fig. 2).

Distribution of the weight scores for the total sample.

Numbers inside the columns represent the mean weight scores and between brackets the score range; the height of the column demonstrates the % of the contribution of the corresponding dimension to the mean total score. In the legends, between brackets, the maximum score for each dimension of the risk stratification tool appears.

Table 1 shows the distribution of patients who were scored on each variable and the impact of excluding a variable on the categorization of the priority level as defined above. There were variables that were scored in a minority of patients (i.e., <5%), namely, “pregnancy,” “unhealthy lifestyle,” “factors related to the patient-health care professional relationship,” “cognitive impairment,” and “treatment adherence” (Supplementary Table 2). The variables that had the greatest impact on the priority categorization (i.e., excluding that variable changed the priority level in ≥3% of the patients) were “pluripathology/comorbidities” (n=24, 12.1%), “analytical variables and other parameters that have an impact on dose adjustment” (n=20, 10.1%), “modification of the regular medication regimen” (n=18, 9.0%), “high-alert drugs” (n=18, 9.0%), “treatment-associated toxicity” (n=18, 9.0%), “polypharmacy” (n=17, 18.3%), “interactions” (n=15, 7.5%), “first course of treatment or change of treatment” (n=14, 7.0%), “third or subsequent line of treatment” (n=13, 6.5%), “antineoplastic drugs with a discontinuous schedule” (n=10, 5.0%), “swallowing difficulty” (n=8, 4.0%), and “nutritional risk” (n=8, 4.0%).

Recommendation for PC interventionThe experts’ recommendations of interventions that form the PC model for patients with solid or hematological malignancies according to their prioritization level are summarized in Table 2.

Main intervention for pharmaceutical care according to the area of intervention and the priority level.

| Area of intervention | Priority level | Recommended interventionsa |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacotherapeutic monitoring | Priority 3 | Validation of antineoplastic and supportive treatment.Reconciliation and review of concomitant medication (self-medication, alternative medicine, etc.) and monitoring of all potential interactions, offering the physician an alternative.Application of a single method of adherence monitoring. |

| Priority 2 | Monitoring and follow-up of antineoplastic treatment activity.Recording of Patient-Related Outcomes (PRO) at each visit.Application of dual method of adherence monitoring. | |

| Priority 1 | Additional contact with the patient between visits by means of teleassistance.Planning of the next visit to the unit in coordination with the health care team to ensure close monitoring.Conducting a clinical interview at every treatment cycle.Involvement of the patient in the Pharmacotherapeutic Plan, sharing with him or her the evolution of his or her objectives and agreeing on actions. | |

| Patient training, education and follow-up | Priority 3 and 2 | Provision of information and resolution of doubts about treatment, prevention, and minimization of adverse reactions.Provision of written information on treatment.Use of tools for self-management: list of reliable websites and apps available.Promotion of the culture of adherence and coresponsibility for treatment results.Adaptation to the patient's needs.Promotion of a healthy lifestyle. |

| Priority 1 | Development of personalized material for each patient and/or caregiver (e.g.: Medication sheet, diary, or similar), in paper or electronic format.Training and education of family members and/or caregivers for the correct follow-up of the patient.Encourage the need to communicate any new process with the patient (new disease, new medication, social problem, etc.).Patient follow-up between visits: Telepharmacy (sms, phone calls, etc.). | |

| Coordination with the health care team | Priority 3 | Information on the telephone number and contact hours with the pharmacist.Unification of criteria and messages between the several health care professionals of the multidisciplinary team (bidirectional communication).Passive coordination with other levels of care, preferably through the EHRcDevelopment of programs aimed at meeting objectives in relation to pharmacotherapy. |

| Priority 2 | Specialized intrahospital coordination (Psycho-Oncology, Psychiatry, and/or Social Services).Provision of scheduled face-to-face Pharmaceutical Care (coinciding with medical visits) or by means of tele-assistance.Recommendation or information on the use of Monitored Dosage System (MDS) in coordination with Community Pharmacy. | |

| Priority 1 | Active coordination with care levels (Pharmacy Offices for Monitored Dosage System (MDS), Social and Health Centers for verification of pharmacological plans).Preparation of periodical reports for the remaining members of the multidisciplinary team on cases of priority level 1 patients (by telephone, registration in the EHR, or in multidisciplinary sessions) and establishment of action algorithms.Provide information to the multidisciplinary team (communication channel to be determined by each center) on priority level 1 patients. E.g.: Call for attention in the information system. |

In the current context of an increased number and duration of oncological treatments and limited healthcare resources, the SM for patients with cancer we have developed is, to our knowledge, the first tool designed to select patients depending on the extent of PC needed. The current available models that define the risk of patients with cancer are mainly based on evaluating the risk of progression in specific types of cancer or on the difficulty for timely diagnostic processes that do not compromise the prognosis of the patients.

The success of cancer treatment is based on the active participation of patients in their treatment. To this end, multidisciplinary care is the starting point, and offering PC tailored to the needs of each patient is needed due to limited resources.

Factors influencing adherence in patients with cancer include demographics, social and health factors, cognitive factors, and clinical factors related to the use of health services.13 To develop this pilot risk SM model and remain consistent with other SM developed by the SEFH,11 we considered most of those factors in order to select patients who can benefit from more extensive PC.

Our results show that several variables seem to contribute to the risk SM, including “pregnancy,” “unhealthy lifestyle,” “factors related to the patient-health care professional relationship,” “cognitive impairment,” and “treatment adherence.” However, in our view, these variables are key for the selection of special patients with more needs because they are important for achieving therapeutic goals. It is possible that the relatively low weight in our model will be the consequence of a low frequency in these patients. Thus, it is estimated that approximately 1 in 1000 pregnancies occur in patients with cancer.14 In the event that cancer treatment cannot be delayed in a patient who is pregnant, exhaustive monitoring should be carried out to respond to and minimize chemotherapy toxicities; this will entail selecting the most appropriate drugs during pregnancy and trying to reduce exposure of the fetus because chemotherapy side effects can have lifelong consequences.15 In this setting, the role of the oncology pharmacist is especially important in designing the patient’s therapeutic plan. In our model, pregnancy raises the patient’s risk to priority 1 indicating their need for more extensive PC.

Regarding variables with relatively low weight in our model, we discuss below the reasons for keeping them in the model. “Unhealthy lifestyle” was defined according to drug and/or alcohol consumption; these are well-known factors associated with nonadherence to treatments,16 and therefore, we considered that they could not be dismissed in our tool. Poor “patient–health professional relationships” are considered one of the main determinants of a lack of adherence to medication.17 Interventions aimed at improving patient–professional communication improve adherence to oral chemotherapy.18 Some cancer treatments are associated with cognitive impairment,19 which, in turn, may condition daily activities, including adherence to medication and/or medical recommendations. The use of the Pfeiffer index in oncology pharmacy consultations is not typical, but it may facilitate the early detection of cognitive impairment and has been recommended by experts for evaluating cognitive function in this setting.20 Lack of adherence is related to lack of response, for example, in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia.21 Although there are no robust figures, data suggest that adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies is an issue for a substantial proportion of patients,22 and pharmacy programs are able to improve adherence to oral chemotherapy.23 Therefore, monitoring adherence is imperative in patients receiving oral antineoplastic drugs, although the results of the monitoring largely depend on the method of assessment.24 In our stratification tool, adherence is evaluated in cases of “suspected nonadherence” by 2 methods, one quantitative and the other qualitative. However, there is solid evidence that health professionals overestimate the adherence of our patients.25 Therefore, it will be necessary to minimize interpretation bias with this item.

We found that the variables that affect the priority level were “pluripathology/comorbidities,” “analytical variables and other parameters that have an impact on dose adjustment,” “modification of the regular medication regimen,” “high-alert drugs,” “treatment-associated toxicity,” “polypharmacy,” “interactions,” “first course of treatment or change of treatment,” “third or subsequent line of treatment,” “antineoplastic drugs with a discontinuous schedule,” “swallowing difficulty,” and “nutritional risk.” These results are not surprising since the vast majority of them were directly related to antineoplastic therapy and its complexity, including its duration and toxicity. Regarding comorbidity, approximately half of patients with cancer show multimorbidity. The presence of multimorbidity potentially affects the development, stage at diagnosis, treatment and outcomes of patients with cancer, including survival.26 Dosage adjustments are related to the toxicity of antineoplastic treatment and compromise dosage intensity, which has been associated with a reduced overall survival.27 Pharmacological interactions pose a potential risk to patient safety and clinical efficacy and, ultimately, can affect patients’ quality of life.28 The role of the oncology pharmacist in detecting both drug–drug interactions and drug interactions with complementary medicines is essential. The expert panel considered that a patient receiving more than 3 lines of treatment for advanced disease is more likely to feel burned out and more difficult to maintain adherence. The first oncology treatment may also be more complex, as it requires rapid adaptation to a cancer diagnosis situation. Dysphagia is related to various conditions, neoplasm type, surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and newer therapies such as epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. It is important to recognize swallowing difficulties to tailor treatments, recommend exercises and specific treatments for concomitant oral complications. Swallowing difficulties have a direct impact on the quality of life of cancer patients.29 Malnutrition is common in cancer patients and is due to both the presence of the tumor and the medical and surgical treatments for cancer. It has a negative impact on quality of life and treatment toxicities, and it has been estimated that up to 10–20% of cancer patients die due to malnutrition rather than from the neoplasm. There is evidence that nutritional issues should be taken into account from the time of cancer diagnosis, and the patient's nutritional risk should be assessed, which is recommended in the ESPEN guidelines.30

Strengths of this project include an expert group of mostly BCOP oncology pharmacists with over 5 years of experience in the field. They are active GEDEFO members, work in hospitals of varying levels, and are located in different regions of Spain. This pilot model was developed based on expert opinions to create a comprehensive framework encompassing all factors influencing the increasing care needs of cancer patients. Cut-off points have been established to identify patients requiring higher levels of PC.

However, the model requires validation in a representative population. A study with over 800 patients across 14 hospital centers has already been conducted, and the results will be published separately. The model defines PC actions aligned with other SEFH models, serving as the ultimate objective. Additionally, assessing whether implementing these actions improves outcomes in cancer patients is crucial.

Contribution to the scientific literatureThis study represents the first published approach to sizing one aspect of healthcare to the needs of an oncology patient. It is a comprehensive model that, once validated in a representative population, will be incorporated into the portfolio of hospital oncology pharmacy services, allowing the best oncology pharmaceutical care to be tailored to the needs of patients.

Ethical considerations and conflicts of interestAll the undersigned authors meet the requirements for authorship. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest directly or indirectly related to the contents of the manuscript. The instructions for manuscript submission and ethical responsibilities have been taken into account in the present work.

FundingThe Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy funded the development of MAPEX, the support of the ASCENDO consultancy and the collaboration Fernando Rico-Villademoros who has collaborated in the writing of the manuscript

The authors would like to thank the SEFH for their efforts in the development and implementation of MAPEX and the MAPEX coordinators for their vision and work, especially Ramón Morillo for his collaborative work and inspiration. Fernando Rico-Villademoros for his help in the preparation of a draft of this manuscript. The ASCENDO consultancy for their support in the development of the Stratification Tool, especially Dolores Mateos, Ana Martinho and Alicia Olivas. All the hospitals where this research has been carried out, especially the collaborating researchers from each hospital who have made this work possible. From the Hospital Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida: Marta Gilabert Sotoca and Judith Rius Perera; from the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela: Manuel Tourís Lores, Elena López Montero, Goretti Durán Piñeiro, Sara Blanco Dorado, Alicia Mosquera Torre, Bibiana Sánchez Iglesias, Eugenia Giugovaz and María Jesús Lamas Díaz; from the Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla: María Ochogavía Sufrategui; from Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca: Laura Menéndez Naranjo and Almudena Mancebo González; from Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Macarena: Úrsula Baños Roldán; from Hospital Corporació de Salut del Maresme i la Selva, Calella: Anna Estefanell Tejero, Dolores Ruíz Poza and Nuria Sabaté Frías; and from Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cádiz.: José Huertas Fernández.

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families who are seen every day in the oncology and oncohaematology pharmacies for their willingness to collaborate with our projects, especially each patient included in this study.