Multiple sclerosis is a chronic demyelinating disease of the central nervous system and long-term disabling. Different disease-modifying treatments are available. These patients, despite being generally young, have high comorbidity and risk of polymedication due to their complex symptomatology and disability.

Objective primaryTo determine the type of disease-modifying treatment in patients seen in Spanish hospital pharmacy departments. Secondary objectives: to determine concomitant treatments, determine the prevalence of polypharmacy, identify the prevalence of interactions and analyze pharmacotherapeutic complexity.

MethodObservational, cross-sectional, multicentre study. All patients with a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and active disease-modifying treatment who were seen in outpatient clinics or day hospitals during the second week of February 2021 were included. Modifying treatment, comorbidities and concomitant treatments were collected to determine multimorbidity pattern, polypharmacy, pharmacotherapeutic complexity (Medication Regimen Complexity Index) and drug–drug interactions.

Results1407 patients from 57 centres in 15 autonomous communities were included. The most frequent form of disease presentation was the relapsing remitting form (89.3%). The most prescribed disease-modifying treatment was dimethyl fumarate (19.1%), followed by teriflunomide (14.0%). Of the parenteral disease-modifying treatments, the two most prescribed were glatiramer acetate and natalizumab with 11.1% and 10.8%. 24.7% of the patients had 1 comorbidity and 39.8% had at least 2 comorbidities. 13.3% belonged to at least one of the defined patterns of multimorbidity and 16.5% belonged to 2 or more patterns. The concomitant treatments prescribed were psychotropic drugs (35.5%); antiepileptic drugs (13.9%) and antihypertensive drugs and drugs for cardiovascular pathologies (12.4%). The presence of polypharmacy was 32.7% and extreme polypharmacy 8.1%. The prevalence of interactions was 14.8%. Median pharmacotherapeutic complexity was 8.0 (IQR: 3.3–15.0).

ConclusionsWe have described the disease-modifying treatment of patients with multiple sclerosis seen in Spanish pharmacy services and characterized concomitant treatments, the prevalence of polypharmacy, interactions, and their complexity.

La esclerosis múltiple es una enfermedad desmielinizante crónica del sistema nervioso central y discapacitante a largo plazo. Existen diferentes tratamientos modificadores de la enfermedad. Estos pacientes, a pesar de ser generalmente jóvenes, tienen elevada comorbilidad y riesgo de polimedicación por su compleja sintomatología y discapacidad.

Objetivo principalDeterminar el tipo de tratamiento modificador de la enfermedad en pacientes atendidos en servicios de Farmacia de hospitales españoles. Objetivos secundarios: conocer los tratamientos concomitantes, determinar la prevalencia de polifarmacia, identificar la prevalencia de interacciones y analizar la complejidad farmacoterapéutica.

MétodoEstudio observacional, transversal y multicéntrico. Se incluyeron todos los pacientes con diagnóstico de esclerosis múltiple y tratamiento modificador de la enfermedad activo a los que se atendió en las consultas de pacientes externos o en los hospitales de día durante la segunda semana de febrero 2021. Se recogieron el tratamiento modificador, comorbilidades y tratamientos concomitantes para determinar patrón de multimorbilidad, polifarmacia, complejidad farmacoterapéutica (Medication Regimen Complexity Index) e interacciones medicamentosas.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 1407 pacientes de 57 centros de 15 comunidades autónomas. La forma de presentación de la enfermedad más frecuente fue la forma remitente recurrente (89,3%). El tratamiento modificador de la enfermedad más prescrito fue dimetilfumarato (19,1%), seguido de teriflunomida (14,0%). De los tratamientos modificadores parenterales, los dos más prescritos fueron el acetato de glatirámero y el natalizumab con un 11,1% y 10,8% respectivamente. El 24,7% de los pacientes tenían 1 comorbilidad y el 39,8% al menos 2 comorbilidades. El 13,3% pertenecía al menos a uno de los patrones definidos de multimorbilidad y el 16,5% pertenecían a 2 o más patrones. Los tratamientos concomitantes prescritos fueron los psicofármacos (35,5%), los antiepilépticos (13,9%) y los antihipertensivos y fármacos para patologías cardiovasculares (12,4%). La presencia de polifarmacia fue del 32,7% y de polifarmacia extrema el 8,1%. La prevalencia de interacciones fue del 14,8%. La mediana de complejidad farmacoterapéutica fue de 8,0 (IQR: 3,3 – 15,0).

ConclusionesSe ha descrito el tratamiento modificador de la enfermedad de los pacientes con esclerosis múltiple atendidos en los servicios de farmacia españoles y se ha caracterizado los tratamientos concomitantes, la prevalencia de polifarmacia, las interacciones, y su complejidad farmacoterapéutica.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system that causes disabling neuroaxonal degeneration in the long term and is characterized by relapse and remission periods1.

In Spain, there are 55,000 patients diagnosed with MS, with an annual incidence of 4.2 cases/100,000 population. Age at diagnosis ranges from 20 to 49 years. Prevalence is 120 cases/100,000 population2, with variability across regions3.

There are four clinical patterns of MS4: relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS); progressive-relapsing MS (PRMS); and two progressive forms: secondary progressive MS (SPMS), and primary progressive MS (PPMS). In most patients (85%), onset of disease occurs in the form of relapsing–remitting MS2. The natural history of the disease begins as RRMS (10–15 years) and evolves into SPMS.

Treatment is aimed at reducing the frequency of flare-ups, decreasing accumulated lesion load, and slowing disability progression. At the moment where this study was conducted, there were 13 disease-modifying treatments available (DMT) which were either immunomodulators or immunosuppressants. DMT have traditionally been classified into first-line and second-line treatments, as a function of their effectiveness and safety. First-line treatments for relapsing presentations are based on immunomodulators (IM interferon beta 1a and SC interferon beta 1b; SC and IM pegylated interferon beta 1a; SC glatiramer acetate; oral teriflunomide; and oral dimethyl fumarate). Second-line treatments are based on immunosuppressants (oral fingolimod, oral cladribine, IV natalizumab, IV ocrelizumab, and IV alemtuzumab). Most of these treatments are indicated for RRMS, whereas Ocrelizumab can be administered for active PPMS, and oral siponimod is only indicated for SPMS.

Clinical practice guidelines5,6 and consensus statements7,8 have been developed for the management of MS. However, treatments are most frequently selected on the basis of the clinical status of the patient, severity of disease, profile of adverse events, desire of pregnancy, convenience and cost. In Spain, all DMT are funded by the National Health System. However, differences in health policies have emerged as a result of the decentralization of health services across the different autonomous communities (and even across hospitals). Likewise, the cost of DMT also differs across regions, which may influence therapeutic decision making and prescription patterns. A national registry of MS patients is not available in Spain; therefore, it is difficult to determine the types of DMT administered to patients and assess changes in prescription patterns.

Advances in disease-modifying therapies over the recent years have made it possible to expand treatment options and delay progression into severe disease. However, MS continues to be the second leading cause of disability in young adults (30–40 years), following cranioencephalic trauma, an age that coincides with the most productive period of life9. As disease progresses, symptoms exacerbate, which adds to morbidity even at young ages. The most frequent symptoms include sensory alterations, paresis, spasticity, fatigue, pain, emotional lability, and coordination disorders.

On another note, as it occurs in the general population, other chronic diseases emerge with age, which also contributes to morbidity. Some comorbidities (with comorbidity defined as any additional disease that co-occurs in a patient with an underlying disease and is not a clear complication of the disease) are more prevalent among MS patients. Comorbidities include depression (23.7%); anxiety (21.9%); cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension (18.6%); hypercholesterolemia (10.9%); or chronic lung disease (10.9%)10,11. The incidence of autoimmune disorders is also higher in MS patients, including thyroid gland disorders and inflammatory bowel disease11,12. In addition, the risk for developing thrombotic events is three times higher in patients with primary progressive MS13.

The presence of comorbidities in MS results in delayed diagnosis of MS and an increased risk of polypharmacy, and contributes to disability progression10 and worsening of quality of life, which may even determine DMT selection.

Polypharmacy, defined as using more than five medications daily14, primarily affects elderly people with chronic diseases. However, several studies15,12 demonstrate that, although patients with MS are generally young, they are at a high risk for polypharmacy due to the complexity of their symptoms. In addition, polypharmacy increases as disability progresses16.

Factors such as age, comorbidities and, particularly, polypharmacy, increase the risk for therapeutic cascades, adverse events, and drug interactions. As a result, these factors may have a negative impact on treatment adherence and cause an increase of hospital admissions10.

In Spain, there is no recent evidence on DMT prescription patterns. In addition, no studies have been conducted to estimate the pharmacotherapy complexity index in MS. On another note, although some studies have been carried out to estimate the incidence of polypharmacy or assess drug interactions and treatment adherence in MS patients, no representative multicentric studies have been performed to date.

The primary goal of this study was to determine DMT prescription patterns in patients attended in outpatient units and day hospitals in Spain. Secondary objectives included identifying concomitant treatments to DMT, determining the prevalence of polypharmacy and drug interactions, and assessing pharmacotherapeutic complexity in these patients.

MethodsThis study was conducted within the framework of a larger observational, cross-sectional, multicentric study, the EM-POINT study. The study population was composed of all patients with a diagnosis of MS who were receiving an active DMT dispensed in outpatient hospital pharmacy consultations or administered in the day hospitals of the participating sites. The study period comprised the second week of February 2021, according to the established cross section. Patients taking part in clinical trials were excluded.

The following variables were collected: demographic (age, sex) and clinical variables (Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]); form of disease presentation (RRMS, PRMS, SPMS, PPMS), and most prevalent associated comorbidities. Multimorbidity patterns were classified as: mechanical-obesity-thyroid; cardio-metabolic; depressive; psychogeriatric; and psychiatric-substance abuse17.

Pharmacotherapy variables were also collected, including: DMT, concomitant prescriptions for the syndromes most frequently associated with MS (depression, fatigue, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, urinary incontinence, spasticity, gait disorders and epilepsy). The presence of polypharmacy and extreme polypharmacy was also recorded, defined as the prescription of five or more medications, and ten or more medications, respectively14. Additionally, an analysis was performed of polypharmacy patterns in these patients: depression-anxiety, cardiovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease17.

Pharmacotherapy complexity was assessed using the Medication Regimen Complexity Index (MCRI)18. Thus, we estimated total pharmacotherapy complexity and analyzed it qualitatively and quantitatively by using the different subsections of this tool. Based on Lexicomp® Drug Interactions, interactions between DMT and concomitant treatments were identified. Finally, interactions were categorized into type X (avoid combination) and type D (consider changing treatment).

Sample size was calculated as a function of the incidence of MS in Spain and its total population. We estimated that 50% of patients would have polypharmacy, assumed a 5% precision, and calculated 95% confidence intervals. As a result, we estimated that 381 patients from across the country were needed to achieve a significant cross section.

Statistical analysisData processing was performed by complete case analysis without imputing missing data. Quantitative variables are presented as means and standard deviation (SD) for normally-distributed variables, and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for odd data.

Qualitative variables are presented as frequencies and percentages.

Statistical analysis was performed using the R Studio v. 1.1.456 software package.

ResultsA total of 1407 patients (68.0% women) of the 57 participating sites were included. Fifteen of the 17 autonomous communities were represented. Median age was 45.6 years (IQR: 38.2–53.2).

The most frequent form of presentation was RRMS (89.3%), whereas only 7.2% of patients had SPMS.

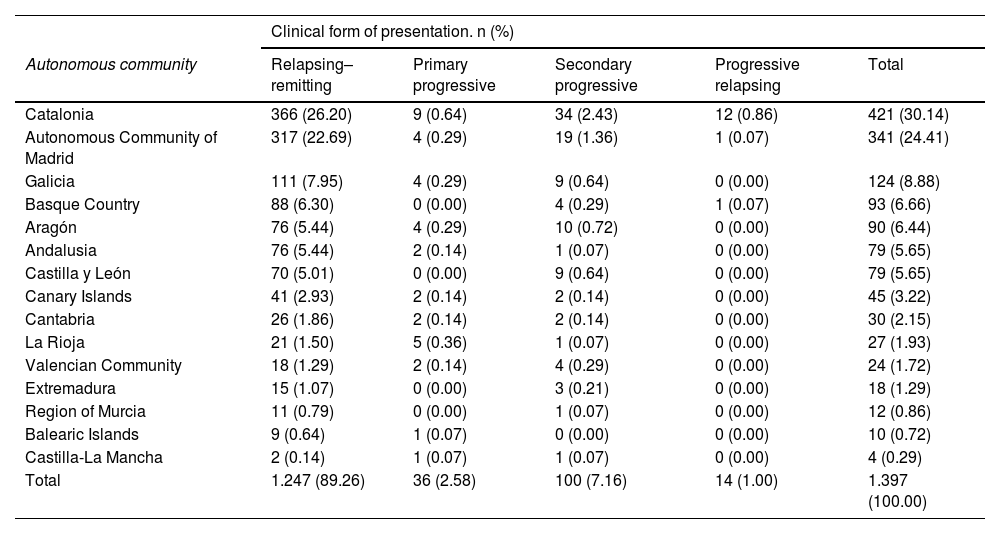

The autonomous communities with the highest representation were: Catalonia, 421 patients; followed by Madrid and Galicia with 341 and 124 patients, respectively. Table 1 shows the representativeness of each autonomous community according to disease symptoms.

Distribution of the clinical form of presentation of the disease by autonomous community.

| Clinical form of presentation. n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous community | Relapsing–remitting | Primary progressive | Secondary progressive | Progressive relapsing | Total |

| Catalonia | 366 (26.20) | 9 (0.64) | 34 (2.43) | 12 (0.86) | 421 (30.14) |

| Autonomous Community of Madrid | 317 (22.69) | 4 (0.29) | 19 (1.36) | 1 (0.07) | 341 (24.41) |

| Galicia | 111 (7.95) | 4 (0.29) | 9 (0.64) | 0 (0.00) | 124 (8.88) |

| Basque Country | 88 (6.30) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (0.29) | 1 (0.07) | 93 (6.66) |

| Aragón | 76 (5.44) | 4 (0.29) | 10 (0.72) | 0 (0.00) | 90 (6.44) |

| Andalusia | 76 (5.44) | 2 (0.14) | 1 (0.07) | 0 (0.00) | 79 (5.65) |

| Castilla y León | 70 (5.01) | 0 (0.00) | 9 (0.64) | 0 (0.00) | 79 (5.65) |

| Canary Islands | 41 (2.93) | 2 (0.14) | 2 (0.14) | 0 (0.00) | 45 (3.22) |

| Cantabria | 26 (1.86) | 2 (0.14) | 2 (0.14) | 0 (0.00) | 30 (2.15) |

| La Rioja | 21 (1.50) | 5 (0.36) | 1 (0.07) | 0 (0.00) | 27 (1.93) |

| Valencian Community | 18 (1.29) | 2 (0.14) | 4 (0.29) | 0 (0.00) | 24 (1.72) |

| Extremadura | 15 (1.07) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (0.21) | 0 (0.00) | 18 (1.29) |

| Region of Murcia | 11 (0.79) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.07) | 0 (0.00) | 12 (0.86) |

| Balearic Islands | 9 (0.64) | 1 (0.07) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 10 (0.72) |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 2 (0.14) | 1 (0.07) | 1 (0.07) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (0.29) |

| Total | 1.247 (89.26) | 36 (2.58) | 100 (7.16) | 14 (1.00) | 1.397 (100.00) |

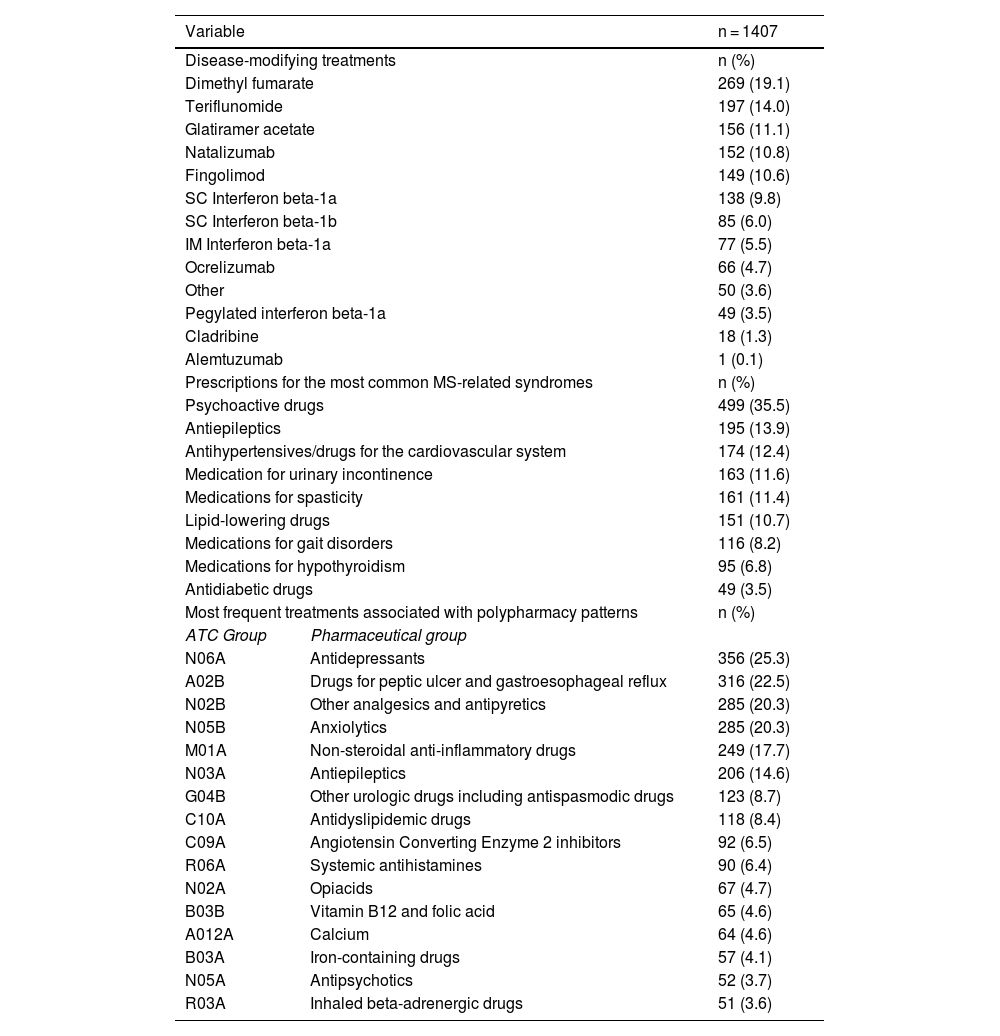

The most frequently prescribed DMT was dimethyl fumarate (19.1%), followed by teriflunomide (14.0%). The two most common parenteral DMT were glatiramer acetate and natalizumab, with 11.1% and 10.8% of use, respectively (Table 2).

Disease-modifying treatments, treatments prescribed for the syndromes most commonly associated with MS, and the most common concomitant treatments associated with polypharmacy patterns.

| Variable | n = 1407 | |

|---|---|---|

| Disease-modifying treatments | n (%) | |

| Dimethyl fumarate | 269 (19.1) | |

| Teriflunomide | 197 (14.0) | |

| Glatiramer acetate | 156 (11.1) | |

| Natalizumab | 152 (10.8) | |

| Fingolimod | 149 (10.6) | |

| SC Interferon beta-1a | 138 (9.8) | |

| SC Interferon beta-1b | 85 (6.0) | |

| IM Interferon beta-1a | 77 (5.5) | |

| Ocrelizumab | 66 (4.7) | |

| Other | 50 (3.6) | |

| Pegylated interferon beta-1a | 49 (3.5) | |

| Cladribine | 18 (1.3) | |

| Alemtuzumab | 1 (0.1) | |

| Prescriptions for the most common MS-related syndromes | n (%) | |

| Psychoactive drugs | 499 (35.5) | |

| Antiepileptics | 195 (13.9) | |

| Antihypertensives/drugs for the cardiovascular system | 174 (12.4) | |

| Medication for urinary incontinence | 163 (11.6) | |

| Medications for spasticity | 161 (11.4) | |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 151 (10.7) | |

| Medications for gait disorders | 116 (8.2) | |

| Medications for hypothyroidism | 95 (6.8) | |

| Antidiabetic drugs | 49 (3.5) | |

| Most frequent treatments associated with polypharmacy patterns | n (%) | |

| ATC Group | Pharmaceutical group | |

| N06A | Antidepressants | 356 (25.3) |

| A02B | Drugs for peptic ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux | 316 (22.5) |

| N02B | Other analgesics and antipyretics | 285 (20.3) |

| N05B | Anxiolytics | 285 (20.3) |

| M01A | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 249 (17.7) |

| N03A | Antiepileptics | 206 (14.6) |

| G04B | Other urologic drugs including antispasmodic drugs | 123 (8.7) |

| C10A | Antidyslipidemic drugs | 118 (8.4) |

| C09A | Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 inhibitors | 92 (6.5) |

| R06A | Systemic antihistamines | 90 (6.4) |

| N02A | Opiacids | 67 (4.7) |

| B03B | Vitamin B12 and folic acid | 65 (4.6) |

| A012A | Calcium | 64 (4.6) |

| B03A | Iron-containing drugs | 57 (4.1) |

| N05A | Antipsychotics | 52 (3.7) |

| R03A | Inhaled beta-adrenergic drugs | 51 (3.6) |

ATC: Anatomical, therapeutic, chemical classification; MS: Multiple sclerosis.

In the autonomous communities with the highest representation, it is worth noting that the most frequent DMT prescriptions in Catalonia and Madrid were the sum of the different forms of interferon and glatiramer acetate (38.5 and 39.6% respectively). In Galicia, the DMT most frequently prescribed DMT included first-line oral DMT (dimethyl fumarate and teriflunomide) with a 35.2% of use vs 33.6% of the sum of interferons and glatiramer acetate.

The median number of comorbidities per patient was (IQR:0–2). Distribution by frequency was as follows: 35.5% of patients did not have any comorbidity; 24.7% had a comorbidity, and 39.8% had two or more comorbidities. Regarding multimorbidity patterns, 21.5% of patients fitted into the mechanical-obesity-thyroid pattern; 8.8% fell into the depressive pattern, and 8.7 and 7.2% fitted into the psychogeriatric and psychiatric-substance abuse pattern, respectively. Additionally, 70.2% of the population did not follow any multimorbidity pattern, whereas 13.3% fitted at least into one of the defined patterns, and 16.5% followed two or more multiborbidity patterns.

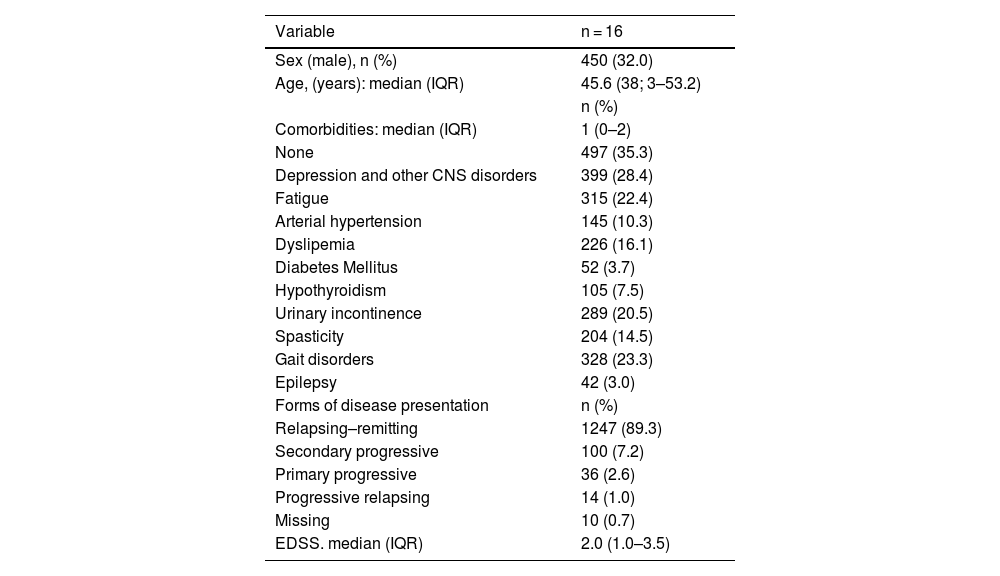

The median EDSS in these patients was 2.0 (IQR 1.0–3.5). Table 3 summarizes the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, form of presentation of MS, and EDSS.

| Variable | n = 16 |

|---|---|

| Sex (male), n (%) | 450 (32.0) |

| Age, (years): median (IQR) | 45.6 (38; 3–53.2) |

| n (%) | |

| Comorbidities: median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) |

| None | 497 (35.3) |

| Depression and other CNS disorders | 399 (28.4) |

| Fatigue | 315 (22.4) |

| Arterial hypertension | 145 (10.3) |

| Dyslipemia | 226 (16.1) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 52 (3.7) |

| Hypothyroidism | 105 (7.5) |

| Urinary incontinence | 289 (20.5) |

| Spasticity | 204 (14.5) |

| Gait disorders | 328 (23.3) |

| Epilepsy | 42 (3.0) |

| Forms of disease presentation | n (%) |

| Relapsing–remitting | 1247 (89.3) |

| Secondary progressive | 100 (7.2) |

| Primary progressive | 36 (2.6) |

| Progressive relapsing | 14 (1.0) |

| Missing | 10 (0.7) |

| EDSS. median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–3.5) |

EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; IQR: Interquartile range; CNS: Central nervous system.

The concomitant prescriptions for the syndromes most frequently associated with MS included psychoactive drugs (35.5%), antiepileptics (13.9%), and antihypertensives and drugs for cardiovascular diseases (12.4%). In addition, the most frequent treatments associated with polypharmacy patterns included antidepressants (25.3%), drugs for peptic ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux (22.5%), other analgesics and antipyretics (NSAIDs not included), and anxiolytics (20.3% each).

Patients were classified by polypharmacy pattern, with 24.9% following the depressive-anxiety pattern; 10.1% the chronic respiratory pattern; and 4.3% the cardiovascular pattern. As many as 39.4% of patients did not fit into any polypharmacy pattern.

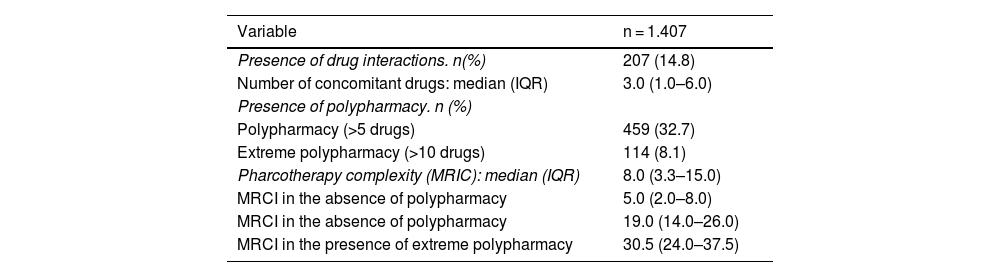

The median of the number of concomitant drugs was 3.0 (IQR: 1.0–6.0); with polypharmacy and extreme polypharmacy having a frequency of 32.7% and 8.1%, respectively, in the study population.

Concerning the presence of drug interactions, prevalence was 14.8%.

Median MRCI was 8.0 (IQR: 3.3–15.0); being dosage regimen the factor with the highest weight in this index. According to the presence or not of polypharmacy, MRCI was lower in patients without polypharmacy: 5.0 (IQR: 2.0–8.0) and increased in patients with extreme polypharmacy: 30.5 (IQR: 24.0–37.5) (Table 4).

Drug interactions, polypharmacy and pharmacotherapy complexity.

| Variable | n = 1.407 |

|---|---|

| Presence of drug interactions. n(%) | 207 (14.8) |

| Number of concomitant drugs: median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–6.0) |

| Presence of polypharmacy. n (%) | |

| Polypharmacy (>5 drugs) | 459 (32.7) |

| Extreme polypharmacy (>10 drugs) | 114 (8.1) |

| Pharcotherapy complexity (MRIC): median (IQR) | 8.0 (3.3–15.0) |

| MRCI in the absence of polypharmacy | 5.0 (2.0–8.0) |

| MRCI in the absence of polypharmacy | 19.0 (14.0–26.0) |

| MRCI in the presence of extreme polypharmacy | 30.5 (24.0–37.5) |

IQR: Interquartile range; MRCI: Medication Regimen Complexity Index.

The characteristics of patients attended in Spanish pharmacy hospitals and their treatments were collected and analyzed, including DMT and other pharmacological treatments. A representative sample was obtained of these patients, both for their characteristics and distribution.

In our study, the most frequent prescriptions were dimethyl fumarate and teriflunomide, two oral first-line medications. Although the active treatment was not reported, Oreja et al.19 performed a national survey over 462 patients with MS and found that the most frequently prescribed medications were fingolimod and natalizumab, which are indicated as second-line treatments. It is worth mentioning that their sample was not representative of the national population, since a large amount of patients were attended at the same center of the autonomous community of Madrid. The authors also obtained a lower EDSS, which indicates that disease was more advanced in their patients, which would explain that the most frequent prescriptions were second line treatments.

Concerning concomitant treatments to DMT, we collected data on the treatments prescribed for common comorbidities in MS. The most prevalent comorbidities were depression, anxiety, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and chronic pulmonary disease11. Notably, these diseases are conditioned by the country of origin of patients. Other comorbidities include diabetes and thyroid gland disorders (not always associated with side effects of DMT). We selected MS symptoms for which there is a specific treatment available12, such as spasticity or urinary incontinence.

In our study, the most frequent prescriptions were psychoactive drugs, followed by antidepressants and medications for peptic ulcer and reflux, all with frequencies exceeding 20% of the study population. These results are not surprising, since depression and anxiety are the most common comorbidities of MS. As opposed to previous studies20, where the most frequent prescriptions were analgesics (27%), contraceptives and hormone therapy (24.3%) and medications for osteoporosis (18.3%). In another study21, the most frequent prescriptions were medications for gastrointestinal disorders (40%), followed by anticoagulants and medications for osteoporosis, both exceeding 30%.

The frequency of polypharmacy has been reported to range from 33 to 90%12. This prevalence should raise concerns, since polypharmacy has been associated with a higher disease burden and poorer self-perception of symptoms such as fatigue and cognitive decline22. Beiske et al. conducted a retrospective study23 to selectively analyze antiepileptic and antidepressant prescriptions in 342 patients. The use of antiepileptic and antidepressant drugs increase polypharmacy in MS patients and the risk for pharmacodynamic interactions due to their action on the CNS. The study revealed that 59% of patients had five or more prescriptions, whereas 7% had 10 or more prescriptions. However, it should be taken into account that mean age of their study population was 53 years vs 45 years in our study, and their mean EDSS was 4.8 vs 2 in our study, two factors that are related to polypharmacy. In another study16, the prevalence of polypharmacy was 56.5% in a population of similar age (48.7 years) but with a higher degree of disability (mean EDSS 3.5), and with a higher proportion of hospitalized patients (52.3%). These factors are associated with a higher number of prescriptions. In a prospective single-center study in 145 outpatients published by the same group 20, the prevalence of polypharmacy was 30.3%. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study to assess DMT in Spain. Our sample size reinforces the consistency of our results. Other studies assessed drug interactions after a new prescription of DMT from a gender-based approach21, whereas other focused on newly diagnosed patients24.

Multiple authors have warned about potential drug interactions in patients with MS and polypharmacy12,16. However, studies on clinically-relevant interactions in specific patient populations are limited. Frahm et al.15 analyzed drug interactions in women of child-bearing age with MS. The authors found antiepileptic and antidepressant and 7.9 potential drug interactions per patients, but only 3% of the total were clinically relevant. In our study, where results are not separated by age or sex, this proportion rises to 14.8%.

Despite its relevance, the prevalence of polypharmacy has not been assessed in the literature. We selected MRCI because it has been validated in our environment. However, there are significant differences in pharmacotherapy complexity, since we focused on a very specific population of patients25.

The main limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design and short study period. As a result, all medications were not represented due to their regimen of administration, a fact that primarily affects second-line DTM. Such is the case of patients receiving alemtuzumab, since it is a long-acting medication that is consequently underrepresented.

In summary, the most frequently prescribed DMT in users of hospital pharmacy services in Spain were oral dimethyl fumarate and teriflunomide, and parenteral glatiramer and natalizumab. The most common concomitant treatments were psychotropic drugs, antiepileptics, antihypertensives and medications for cardiovascular disease. Polypharmacy was present in a third of patients, and another third of patients had extreme polypharmacy. Some patients experienced drug interactions during treatment, with a high pharmacotherapy complexity.

Contribution to the scientific literatureThis paper assesses the frequency and distribution of use of disease-modifying treatments in patients with multiple sclerosis in Spain. The results of this study provide an insight into MS patients using pharmacy services in our country. Secondary objectives include identifying concomitant treatments to DMT, determining the prevalence of polypharmacy, identifying the prevalence of drug interactions and analyzing the pharmacotherapy complexity of these patients.

This study provides valuable information about the characteristics of these MS patients from a very appropriate perspective to hospital pharmacists.

ContributionsAlejandro Santiago Pérez, Santos Esteban Casado and Miriam Álvarez Payero contributed to the design, intellectual content, literature search, clinical trial search, data analysis, drafting, edition and revision of the manuscript.

Santos Esteban Casado and Miriam Álvarez Payero also contributed to data collection.

Santos Esteban Casado contributed to statistical analysis.

Ángel Escolano Pueyo, Ángel Guillermo Arévalo, Nuria Padullés, Pilar Diaz and Ana María López contributed to the definitin of the intellectual content, data collection and revision of the manuscript.

Pilar Diaz and Ana María López also contributed to the study design.

The eight authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Accountability and assignment of rightsAll authors accept responsibility as defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (available at http://www.icmje.org/).

In the event of publication, the authors assign exclusively the right of reproduction, distribution, translation and public presentation (by any sound, audiovisual or electronic means) of our manuscript to Farmacia Hospitalaria and, by extension, to the SEFH.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research on Medicines for Human use of Gregorio Marañón University Hospital of Madrid (April 9, 2021).

We thank the Ethics Committee for Research on Medicines for Human Use of Gregorio Marañón University Hospital for their work, the researchers at participating sites, the Spanish Group of Pharmacy Care of Neurological Diseases for their support, and the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy for funding and supporting this study.