Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use has grown considerably, although there is little research on the topic in Spain. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of complementary medicine use in adult cancer patients at the same time as they were receiving conventional treatment in a Spanish referral cancer centre.

MethodAn observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted in the Ambulatory Treatment Unit during 2 consecutive weeks in March 2015. Adult patients who were receiving intravenous chemotherapy were included. Study variables were obtained from a questionnaire and medical records.

Results316 patients were included. 32.3% of the patients reported complementary medicine use during this period and 89% were ingesting products by mouth, herbs and natural products being the most commonly used. 81% of patients started to use complementary medicine after diagnosis, and family/friends were the main source of information. 65% of the patients reported improvements, especially in their physical and psychological well-being. Significant predictors of CAM use were female gender (P=0.028), younger age (P<0.001), and secondary education (P=0.009). Conclusions: A large proportion of cancer patients receiving intravenous chemotherapy also use complementary medicine, which they mainly take by mouth. Due to the risk of chemotherapy-CAM interactions, it is important for health-professionals to keep abreast of research on this issue, in order to provide advice on its potential benefits and risks.

La popularidad de la medicina alternativa y complementaria entre los pacientes oncológicos ha incrementado, pero aún se dispone de poca información acerca de su empleo en España. El objetivo principal de este estudio fue determinar la prevalencia del uso de medicina complementaria en pacientes oncológicos adultos que reciben tratamiento en un centro autonómico español de referencia.

MétodoEstudio observacional, descriptivo y transversal llevado a cabo en un Hospital de Día de oncología durante 2 semanas de marzo de 2015. Se incluyeron pacientes adultos que recibían tratamiento con quimioterapia intravenosa. Las variables del estudio se obtuvieron a través de un cuestionario y de la historia clínica.

ResultadosFueron incluidos 316 pacientes; el 32,3% estaba usando algún tipo de medicina complementaria en ese momento, y el 89% de ellos lo hacía a base de una ingesta oral de sustancias, principalmente hierbas y productos naturales. El 81% de los pacientes inició la medicina complementaria tras el diagnóstico, siendo la fuente de información principal familiares/amigos. El 65% refirió sentir mejoría, principalmente bienestar físico y psíquico. Los predictores significativos de uso de MAC fueron: ser mujer (p=0,028), edad joven (p<0,001) y un nivel educativo medio (p=0,009).

ConclusionesUna proporción importante de los pacientes oncológicos que reciben quimioterapia intravenosa usan simultáneamente medicina complementaria, y esta consiste principalmente en una ingesta oral de preparados. Debido al riesgo de interacción con el tratamiento, es importante la formación de los profesionales sanitarios en este ámbito, con el fin de poder aconsejar a los pacientes acerca de sus potenciales beneficios y riesgos.

The use of CAM among cancer patients is high and is also higher than its use in the general population1-2. Most of the information on this topic has been provided by studies conducted in the United States, which show that up to 90% of these patients use complementary medicine3-5. However, there are few European studies on this topic. In 2005, a European study was conducted across 14 countries. It was found that the overall prevalence of CAM use among cancer patients was 35.9%. Spain had the fourth lowest consumption (29.8%)6.

CAM users are more likely to be younger, women, and married and to have a high educational level and annual income6-7. CAM use is more common in patients with breast, lung, and gastrointestinal cancer8,9. Dietary supplements, herbal remedies, homeopathic remedies, vitamins, and minerals are some of the most popular types of CAM used by these patients10-11. These types of products are taken by mouth and therefore could affect the therapeutic safety of patients, as suggested by studies that have found interactions between a range of substances, mainly herbs, and chemotherapy12-13.

In Spain, the prevalence of CAM use is unknown in patients diagnosed with cancer and, in particular, in those who continue treatment. This aspect is of particular interest because of the potential risk of interaction.

The main objective of this study was to determine the proportion of cancer patients who use complementary medicine while receiving intravenous chemotherapy prescribed according to usual clinical practice.

Secondary objectives were: to investigate the type and duration of CAM use, the sources of information used, the effect of CAM as perceived by patients, and to characterise the socio-demographic and clinical profile of CAM users.

MethodsDesign and patientsAn observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted in the ambulatory treatment unit of the reference hospital of the Autonomous Community of Navarre, Spain.

Patients referred for treatment during 2 consecutive weeks in March 2015 were invited to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were: being at least 18 years, having a confirmed diagnosis of cancer, and receiving intravenous chemotherapy. The exclusion criterion was: language difficulties in the oral and written comprehension of the questionnaire.

The participants gave informed written consent in which they authorized access to their clinical history. They were also given an information sheet with a contact telephone number.

The variables studied were obtained through electronic medical records and a interviewer-guided questionnaire, which was completed in the treatment rooms. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and current Spanish legislation (ministerial order SAS/3470/2009 for observational studies). The protocol was assessed by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Autonomous Community of Navarre and classified by the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency as a “Postauthorization Study with a design other than prospective follow-up” (Spanish acronym: EPA-OD).

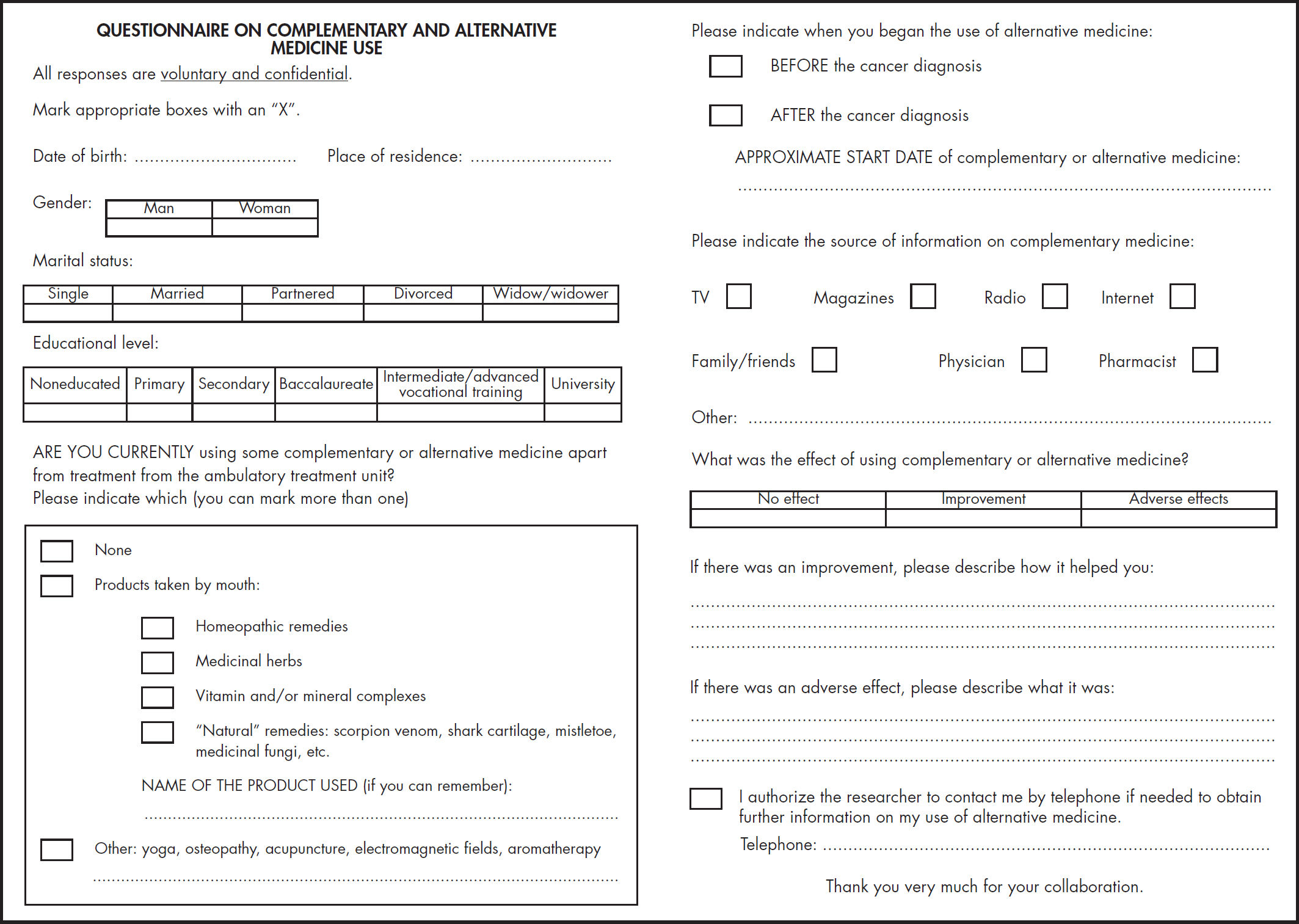

QuestionnaireIn the absence of a validated questionnaire, one was designed following a review of the literature and subsequently assessed by an oncologist, two epidemiologists, and a clinical pharmacist (Figure 1). The questionnaire comprised 9 questions that collected the following information:

- •

Socio-demographic data: gender, age, place of residence, marital status, and educational level.

- •

Current CAM use: type of CAM used, beginning of CAM use (before or after cancer diagnosis), duration of CAM use, sources of information, and perceived results (no result, improvement, or adverse effects).

Based on whether the complementary medicine was taken by mouth or otherwise, the types of CAM were classified into two large groups: “Oral intake of some product” or “Other”. If the patient marked the box “Oral intake”, they were asked to identify the products as homeopathic remedies, herbs, vitamins and/or minerals, or natural remedies. Changes in diet and food were not considered as CAM, except for food marketed in the form of capsules and tablets, among others, and products from traditional Chinese medicine taken by the patient with therapeutic intent. If the patient marked the box “Other”, they were asked to identify the approach (e.g., yoga, osteopathy, acupuncture, electromagnetic fields, etc). Both sections contained a free field for further comments. The last item requested a telephone number. If authorized by the participant, the researcher could call the patient to obtain more information on the type of CAM used.

Subsequently, the clinical data of the patients were collected using the electronic medical history system of the Navarre Health Service:

- •

Cancer diagnosis (type of tumour, stage, and time of diagnosis).

- •

Number of cancer treatment lines received.

- •

Surgery and/or radiotherapy as treatment.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS V22.0 software package for Windows. A descriptive study was conducted using frequency and proportion analysis for qualitative variables (expressed as number and percentage), and position measurements for the quantitative variables age and duration of CAM use.

Simple logistic regression analysis was used to determine the potential predictors of CAM. We estimated the raw odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

ResultsParticipantsDuring the 2-week sampling period, 539 people attended the ambulatory cancer treatment unit for intravenous treatment. Of these patients, 58 (10.8%) did not receive treatment and therefore did not access the rooms in which the study was being conducted. A further 108 patients could not be contacted. At this point the initial sample comprised 373 patients.

However, 53 patients decided not to take part and 4 patients were excluded: 3 were excluded due to their inability to understand the questionnaire because of their lack of knowledge of the Spanish language, and 1 patient was excluded due to a psychiatric diagnosis.

Thus, the final sample comprised 316 patients (84.7% of the initial sample). Twelve patients (3.8%) were contacted by telephone to obtain further information.

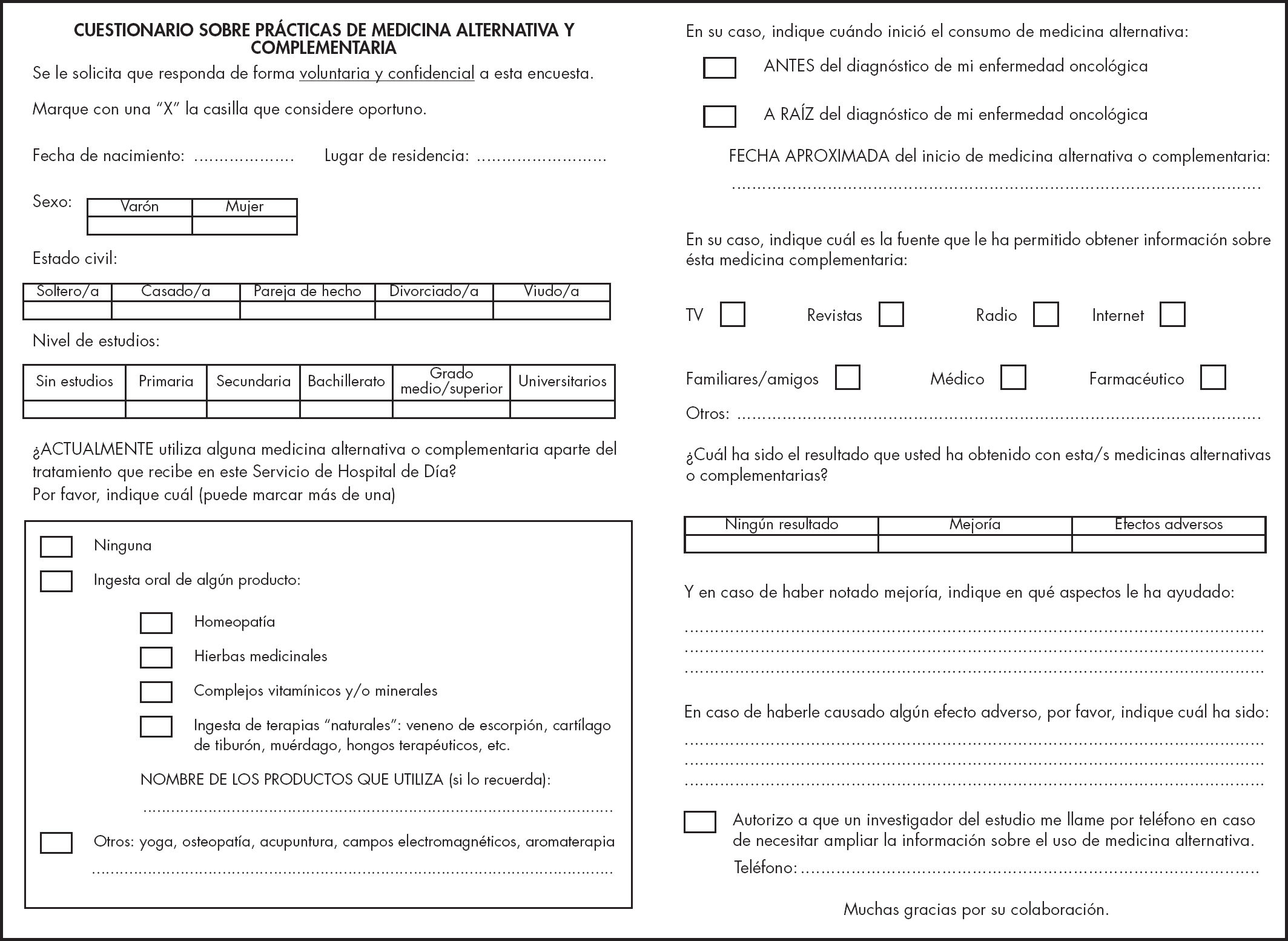

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristicsThe sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Woman | 173 | 54.7 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 166 | 52.5 |

| Rural | 150 | 47.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 47 | 14.9 |

| Married | 228 | 72.2 |

| Partnered | 9 | 2.8 |

| Divorced | 10 | 3.2 |

| Widow/widower | 21 | 6.6 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.3 |

| Age | ||

| ≤ 55 y | 94 | 29.7 |

| > 55 y | 222 | 70.3 |

| Educational level | ||

| No education or primary | 144 | 45.6 |

| Secondary* | 122 | 38.6 |

| Higher† | 50 | 15.8 |

| Type of cancer | ||

| Breast | 102 | 32.3 |

| Colorectal | 80 | 25.3 |

| Lung | 44 | 13.9 |

| Gynaecological | 20 | 6.3 |

| Head-neck | 15 | 4.7 |

| Gastric | 11 | 3.5 |

| Pancreatic | 10 | 3.2 |

| Other‡ | 32 | 10.2 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.6 |

| Cancer grade§ | ||

| I | 34 | 10.8 |

| II | 42 | 13.3 |

| III | 37 | 11.7 |

| IV | 202 | 63.9 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.3 |

| No. treatment lines|| | ||

| 1 | 152 | 48.1 |

| 2-3 | 115 | 36.4 |

| ≥ 4 | 48 | 15.2 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.3 |

| Total | 316 | 100 |

A total of 173 women (54.7%) participated in the study, and the mean age of the patients was 61 years (range, 24-85 years). Almost half of the participants lived in rural areas and almost three-quarters of the participants were married. In total, 16% had a university degree.

The most common diagnosis was breast cancer (32.3%), followed by colorectal and lung cancer. The median time elapsed since diagnosis was 12 months (range, 0-266 months). A total of 222 patients (70%) had undergone surgical intervention and 138 (44%) had received radiotherapy. Ten (3.2%) patients were participating in clinical trials at the time of their inclusion in the study.

CAM UseThe simultaneous use of CAM and conventional treatment with chemotherapy was reported by 102 patients (32.3%).

In total, 89% of the participants who used CAM took preparations by mouth. The most commonly ingested products were herbs (n = 60, 66%), followed by natural remedies (n = 35, 38.5%), vitamins/minerals (n = 32, 35.2%), and homeopathic remedies (n = 16, 17.6%).

A total of 51 different herbs were being used. The most commonly used herbs were turmeric (11.7%) followed by cat's claw (8.3%), liquorice (8.3%), thyme (8.3%), thistle (6.7%), melissa (6.7%), and echinacea (5%). A total of 33 different natural remedies were in use. Of these, the most common were medicinal fungi used in traditional Chinese medicine (14.3%), lactobacillus (14.3%), royal jelly (11.4%), propolis (11.4%), algae such as spirulina and blue-green algae (8.6%), saccharomyces (8.6%), radish (5.7%), black garlic (5.7%), and ginger (5.7%). The most common vitamin supplements used were vitamin C (50%), followed by B vitamins (31.3%), and vitamin E (18.8%). The most common mineral salts used were zinc (21.9%), followed by magnesium (15.6%), bicarbonate (9.5%), and copper (9.4%). The most common homeopathic products used were Miracle Mineral Supplement (MMS; composition sodium chlorite, hemlock, and carcinosinum), which was taken by 43.8% of the participants who used homeopathy, and Schussler's Salts (31.3%).

Of the total number of CAM users, 37 (36.3%) practiced “mind-body interventions”, “manipulation and body-based methods”, and/or “energy therapies”. Of these practices, the most common were yoga, reiki, the application of electromagnetic fields, salt water baths, acupuncture, hyperthermia, and relaxation exercises.

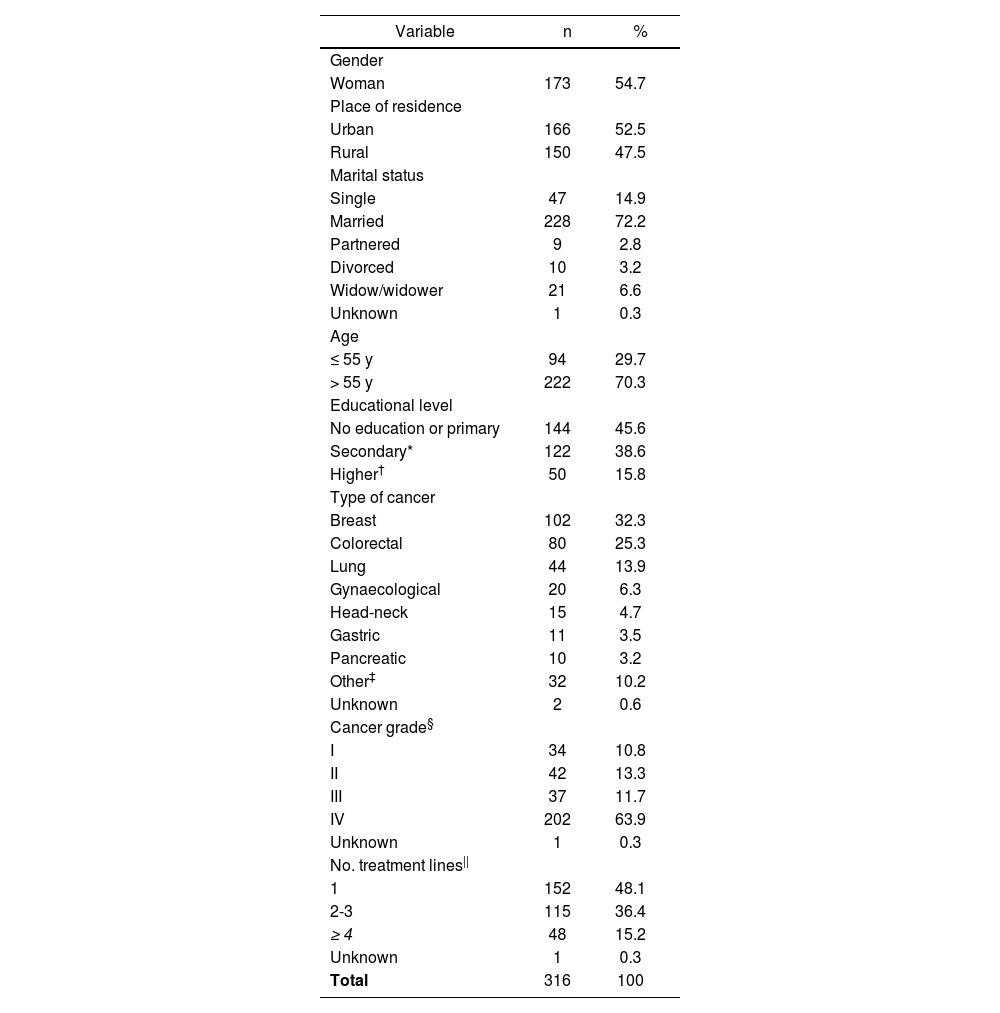

In total, 81.4% of the CAM users started to use it after cancer diagnosis (Table 2). The median duration of use was 4.5 months (range, 0-180 months).

Answers regarding the use of Complementary Medicine

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Beginning of CAM use (n=102) | ||

| Before the diagnosis | 16 | 15.6 |

| After the diagnosis | 83 | 81.4 |

| NN/NR | 3 | 3 |

| Sources of information* | ||

| Television | 0 | 0 |

| Magazines | 2 | 2 |

| Radio | 1 | 1 |

| Internet | 9 | 8.8 |

| Family/friends | 70 | 68.6 |

| Health care professionals† | 8 | 7.8 |

| Other | 19 | 18.6 |

| NN/NR | 7 | 6. 9 |

| Perceived effect (n=102) | ||

| None | 27 | 26.5 |

| Improvement | 66 | 64.7 |

| Adverse effects | 1 | 1 |

| NN/NR | 8 | 7.8 |

Abbreviations: NN/NR, not known/did not reply.

The most common sources of information about CAM were relatives or friends (Table 2). Four patients learned of CAM through a homeopath and 3 through herbalisms.

A total of 64.7% of the CAM users perceived some kind of improvement with its use (Table 2). One adverse effect was reported, which was described as stomach acidity after taking a commercial preparation of echinacea and cat's claw. Of the patients who started using CAM after the cancer diagnosis, 52 (63%) reported that CAM was helping them in some way: 24 (29%) considered that CAM improved their physical and mental strength, 20 (24.1%) thought that it helped to alleviate the adverse effects of treatment, 14 (16.9%) believed that it helped to strengthen their immune system, and 2 (2.4%) considered that it helped them fight cancer.

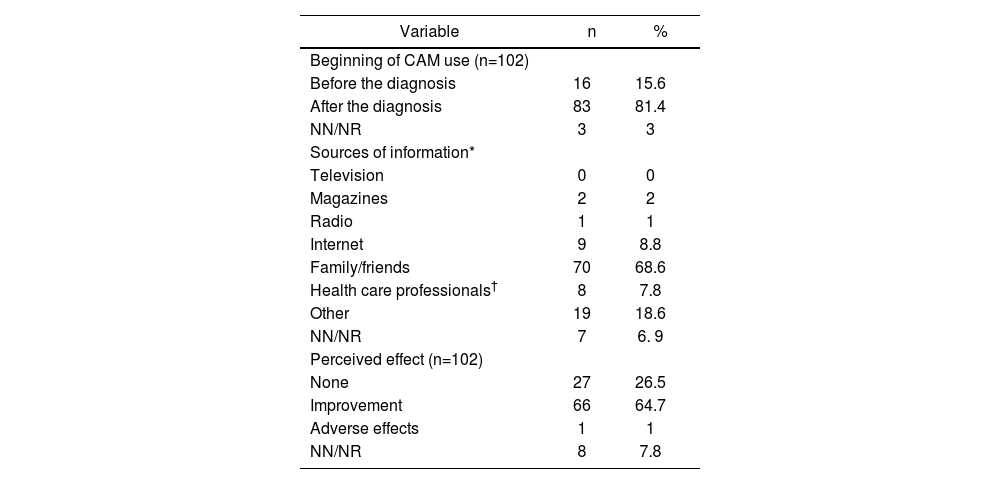

Characteristics that influence CAM useThe potential predictors of CAM use in relation to sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 3. Female gender was positively associated with CAM use. Women were estimated to have 1.72 times (95%CI 1.06-2.80, P = 0.028) more risk of CAM use than men. Significant differences were found in CAM use by age. Taking age as a continuous variable, it was found that CAM use decreased per completed year (OR: 0.96; 95%CI 0.94-0.98; P<.001). The risk of CAM use in patients with secondary education was double that of patients with no or primary education (95%CI 1.19-3.38; P = 0.009).

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics influencing CAM use

| Variable | CAM use | OR (95%CI)* | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO n (%) | Yes n (%) | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Man | 106 (74.1) | 37 (25.9) | (reference) | |

| Woman | 108 (62.4) | 65 (37.6) | 1.72 (1.06-2.80) | 0.028 |

| Age | ||||

| < 55 y | 50 (53.2) | 44 (46.8) | (reference) | |

| > 55 y | 164 (73.9) | 58 (26.1) | 0.40 (0.24-0.66) | <0.001 |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 117 (70.5) | 49 (29.5) | (reference) | |

| Rural | 97 (64.7) | 53 (35.3) | 1.31 (0.81-2.09) | 0.270 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 36 (76.6) | 11 (23.4) | (reference) | |

| Married | 148 (64.9) | 80 (35.1) | 1.77 (0.85-3.67) | 0.125 |

| Partnered | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | 2.62 (0.60-11.48) | 0.202 |

| Divorced | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | 1.40 (0.31-6.36) | 0.661 |

| Widow/widower | 17 (81.0) | 4 (19.0) | 0.77 (0.21-2.77) | 0.689 |

| Educational level | ||||

| No/primary | 107 (74.3) | 37 (25.7) | (reference) | |

| Secondary‡ | 72 (59.0) | 50 (41.0) | 2.01 (1.19-3.38) | 0.009 |

| Higher§ | 35 (70.0) | 15 (30.0) | 1.24 (0.61-2.52) | 0.554 |

| Type of cancer | ||||

| Breast | 68 (66.7) | 34 (33.3) | (reference) | |

| Colorectal | 55 (68.8) | 25 (31.2) | 0.91 (0.49-1.70) | 0.766 |

| Lung | 31 (70.5) | 13 (29.5) | 0.84 (0.39-1.81) | 0.653 |

| Other | 60 (66.7) | 30 (33.3) | 1.00 (0.55-1.82) | 1.000 |

| Time of diagnosis | ||||

| < 12 mo | 107 (65.6) | 56 (34.4) | (reference) | |

| 13-35 mo | 45 (62.5) | 27 (37.5) | 1.15 (0.64-2.04) | 0.642 |

| > 36 mo | 62 (76.5) | 19 (23.5) | 0.59 (0.32-1.08) | 0.084 |

| Cancer grade | ||||

| IV | 135 (66.8) | 67 (33.2) | (reference) | |

| Other | 79 (69.9) | 34 (30.1) | 0.87 (0.53-1.43) | 0.574 |

| Surgery† | ||||

| No | 68 (73.1) | 25 (26.9) | (reference) | |

| Yes | 146 (65.8) | 76 (34.2) | 1.42 (0.83-2.42) | 0.203 |

| Radiotherapy† | ||||

| No | 114 (64.4) | 63 (35.6) | (reference) | |

| Yes | 100 (72.5) | 38 (27.5) | 0.69 (0.42-1.12) | 0.129 |

| No. treatment lines | ||||

| 1 line | 104 (68.4) | 48 (31.6) | (reference) | |

| >1 lines | 110 (67.1) | 54 (32.9) | 1.06 (0.66-1.71) | 0.798 |

Abbreviations: CAM, complementary and alternative medicine.

Around half of the patients participating in clinical trials stated that they were using CAM at the time of the study. However, no statistical difference was found in CAM use between these patients and those not participating in trials (OR: 2.16; 95%CI 0.61-7.62).

DiscussionLittle information is available on CAM use among people diagnosed with cancer in Spain. The present study provides preliminary information on the frequency of CAM use and the type of CAM used by patients receiving intravenous treatment. The justification of this study derives from the risk of interaction between CAM and conventional treatment.

The prevalence of CAM use found in this study was slightly higher than that referred by the only European multicentre study on CAM use in cancer patients for the overall Spanish population (29.8%) 6. These data are in line with those of previous studies on CAM in the field of oncology. In 1998, a systematic review of 26 studies of cancer patients in 13 countries showed that the average prevalence of CAM use was 31%14. However, due to the growing popularity of CAM, higher rates of CAM use were to be expected in the present study. In fact, CAM use has been documented in 64% to 90% of cancer patients in the United States4,5 and close to 50% in Asian countries15,16,17. This high prevalence may be related to the racial and cultural diversity of these countries, and the influence of Western and Eastern CAM practices. Studies have found high levels of CAM use in Europe, ranging from 45% to 51%9,18,19. However, an Italian study in which only current CAM use was assessed, as the present study, found a prevalence of 14%20.

Direct comparisons between the results of this study and previous studies should be made with caution, because of potential differences in sample type, sample size, methodology, and conceptualization (the definition and type of therapies considered as CAM). Due to staff shortages and time constraints, this study excluded patients being treated with oral chemotherapy, but included cancer patients receiving intravenous treatment. The special diets or juices that were included in other studies 21,22 were not included as CAM. This study only included food when it was taken as commercially capsules, tablets, and so on, or traditional Chinese medicine products15. High-protein nutritional supplements were also excluded because they form part of the conventional health care of these patients. White, green, red, and black tea were not defined as CAM, given the difficulty involved in determining whether they were used with therapeutic intent. This aspect differs from other studies, which document the use of green tea as CAM4,5,6,15. These limitations in the definition of CAM, and the fact that their current use alone was assessed, are possible causes of the lower prevalence found in the present study.

The most common type of CAM used by the participants were products taken by mouth, in contrast to practices related to the body or mind. The most commonly used substances were herbs, natural remedies, and vitamins/ minerals, as has already been documented in other studies11,19,23. This aspect reflects the attractiveness of “natural” therapies and remedies to patients, but it is precisely these substances that may involve the greatest risk6. In fact, pharmacokinetic interactions have been identified between certain herbs and natural products and chemotherapy: preclinical studies24-25 have found that garlic, ginseng, echinacea, and soy are CYP450 inhibitors. Thus, they can decrease the elimination of cytostatic drugs and increase their toxicity. In fact, garlic and echinacea were used by the study patients. Other substances used by the patients that interact with chemotherapeutic drugs were liquorice, reishi, radish, and ginger26. The most commonly used vitamin supplement was vitamin C, which is known to interact with cancer drugs such as methotrexate or imatinib27.

The majority of patients (81%) started CAM after cancer diagnosis. As found in other studies6-7, the most important sources of information on CAM were word-of-mouth or relatives and friends, whereas patients only rarely consulted health professionals. It is clear that health care professionals need to increase their awareness and knowledge of CAM use, so that they can become the point of reference in the integral treatment of the patient. The hospital pharmacist can play an important role in this process, particularly in the analysis of potential interactions between conventional and complementary therapy. It would be useful to implement alert systems that include these products in pharmaceutical validation and dispensing software.

One-quarter of the patients using CAM claimed they did not feel any improvement with CAM but continued to use it. The concept of “hope” may be a fundamental reason for the use of CAM6. The beneficial aspects of CAM use more frequently reported by the patients were similar to the main reasons for CAM use found in other studies: to obtain a good level of general health, improve physical and emotional well-being, and boost the immune system6-7,28. Although the questionnaire contained specific items on the effect of CAM, the improvements perceived by the patients could have been influenced by the effects of chemotherapy, given that both treatment modalities were used simultaneously.

Three variables were predictive of CAM use: female gender, young age, and secondary education. The first two variables have been identified as predictors by other studies6,29. Increased CAM use has also been associated with patients with higher education6,8 and with advanced stages of the disease30.

This study may have some limitations. On the one hand, patients were asked to indicate the type of CAM used by classifying it into a specific category in the questionnaire. Since it is common for patients to use more than 1 type of CAM, bias may have been present in relation to recall and knowledge of the type of CAM. In order to minimize this possibility, the patients who were unable to recall these details during the interview were contacted by telephone. A follow-up visit would have been useful to physically see the products used and thus classify them. However, due to time constraints, the researchers were unable to do so. On the other hand, the participation of two researchers in the interviews may have caused interviewer bias due to the effect that different oral and body language may have on patient responses. In order to minimize this possibility, both interviewers participated in designing the questionnaire, and agreed on the criteria for the definition of CAM and its classification.

A significant number of the patients were using CAM at the same time as their conventional medical treatment. Given that CAM is mainly taken by mouth, there is a potential risk of CAM-chemotherapy interaction. As this aspect was not an objective of the present study the magnitude of this problem remains unknown. We believe that health care professionals need to become aware of the importance of investigating CAM use among patients and to be able to advise them. This study found a statistically significant association between CAM use and female gender, younger age, and secondary education. This finding could prove useful in identifying potential CAM users. Future studies could investigate both the use of CAM in groups of patients with a specific type of cancer and potential CAM-chemotherapy interactions.

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of complementary medicine use among cancer patients receiving medical treatment with chemotherapy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate this topic in Spain. Although the prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among such patients has been documented, most of this information comes from the United States. This study shows that one-third of the patients receiving intravenous chemotherapy in ambulatory treatment units were simultaneously using other types of treatment generally taken by mouth (89%). These treatments mainly comprised herbs and natural remedies. The diversity of products was high because of the large number of ingredients included in each preparation. The high number of patients taking CAM contrasts with the low number of patients (8%) who consulted health professionals about complementary medicine. Significant predictors of CAM use were female gender, younger age, and secondary education.

Regardless of the position of health professionals toward complementary medicine, this study demonstrates that patients make use of such treatment due to the physical-emotional impact of a diagnosis of cancer and its treatment. Given the prevalence of use of complementary medicine and low number of consultations with healthcare professionals, it is clear that training in this field is needed such that the medical professional can provide advice on the effectiveness of complementary medicine and on any contraindications. The role of the hospital pharmacist is relevant during the patient interview and when reviewing possible interactions between the preparations used and chemotherapy in order to ensure its safety and efficacy.

El uso de Medicina Alternativa y Complementaria (MAC) entre los pacientes oncológicos es elevado y superior al de la población general1-2. La mayoría de la información procede de Estados Unidos, donde los estudios muestran un consumo de hasta el 90% en estos pacientes3-5. Sin embargo, disponemos de pocos datos en Europa. En el año 2005 se llevó a cabo un estudio europeo en el que participaron 14 países, con una prevalencia de empleo de MAC en pacientes oncológicos del 35,9%, siendo España el cuarto país de menor consumo (29,8%)6.

Se ha asociado el uso de MAC a pacientes jóvenes, mujeres, casadas, con alto nivel educativo e ingresos anuales6-7. En cuanto al tipo de diagnóstico, es más habitual en pacientes con cáncer de mama, pulmón y gastrointestinal8,9. Algunos de los tipos de MAC más populares entre estos pacientes son los suplementos dietéticos, productos de herboristería, homeopatía, vitaminas y minerales10-11. Todas ellas son prácticas de MAC que suponen la ingesta oral de ciertos productos, y podrían por ello afectar a la seguridad terapéutica de los pacientes, ya que se han descrito interacciones entre ciertas sustancias, principalmente plantas, y la quimioterapia12-13.

En nuestro medio se desconoce la prevalencia de empleo de MAC en los pacientes diagnosticados de cáncer y, en concreto, en aquellos que siguen tratamiento, en los que resulta de especial interés por el riesgo de interacción que puede existir.

El objetivo principal de este estudio es determinar la proporción de pacientes oncológicos que utilizan medicina complementaria al tratamiento antineoplásico intravenoso prescrito de acuerdo a la práctica clínica habitual.

Los objetivos secundarios planteados son: analizar el tipo y tiempo de empleo de MAC, las fuentes de información empleadas, conocer los resultados percibidos por los pacientes acerca de los tratamientos complementarios, y realizar una caracterización socio-demográfica y clínica de la población consumidora de MAC.

MétodosDiseño y pacientesSe llevó a cabo un estudio observacional, descriptivo y transversal, en el Hospital de Día de Oncología del centro de referencia de la Comunidad Autónoma de Navarra.

Se invitó a participar en el estudio a los pacientes citados a tratamiento durante dos semanas consecutivas de marzo de 2015. Los criterios de inclusión fueron: tener 18 años o más, un diagnóstico de cáncer confirmado y estar recibiendo tratamiento antineoplásico intravenoso en ese momento. Se excluyeron aquellos pacientes que presentaban dificultades lingüí sticas tanto en la comprensión oral como escrita del cuestionario.

Se solicitó la firma del consentimiento informado por escrito a los participantes, en la que autorizaban el acceso a la Historia Clínica, y se les entregó una Hoja de Información con un teléfono de contacto.

Las variables estudiadas se obtuvieron mediante un cuestionario guiado por entrevista a pacientes, que se cumplimentaba en las salas de tratamiento, y la Historia Clínica Informatizada. El estudio se llevó a cabo de acuerdo con la Declaración de Helsinki así como con la legislación vigente en España (orden ministerial SAS/3470/2009, de estudios observaciona- les). El protocolo fue evaluado por el Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica (CEIC) de la Comunidad Autónoma y clasificado por la Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios como un “Estudio Posautorización con Otros Diseños diferentes al de seguimiento prospectivo” (EPA-OD).

CuestionarioDebido a que no existe un cuestionario validado, se diseñó tras una revisión de la literatura y fue evaluado por un oncólogo, dos epidemiólogos y un farmacéutico clínico (Figura 1). Constaba de 9 preguntas y recogía la siguiente información:

- •

Datos socio-demográficos: sexo, edad, lugar de residencia, estado civil y nivel de estudios.

- •

Preguntas sobre el empleo actual de MAC: tipo de MAC utilizada, momento de inicio de MAC (previo o posterior al diagnóstico oncológico), tiempo consumiendo MAC, fuentes de información y resultados percibidos (ningún resultado, mejoría o efectos adversos).

Los tipos de MAC se englobaron en dos grandes grupos, basándose en si la medicina complementaria suponía ingerir algún producto o no: “Ingesta oral de algún producto” u “Otros”. Si marcaban la casilla “Ingesta oral”, se pedía que identificasen si se trataba de productos homeopáticos, hierbas, vitaminas y/o minerales o terapias naturales. No se consideraron como MAC los cambios en la dieta ni los alimentos, a excepción de los formulados comercialmente como cápsulas, comprimidos, etc. y los productos de la medicina tradicional china, que fuesen tomados por el paciente con intención terapéutica. En el caso de rellenar la casilla “Otros”, se solicitaba que escribiesen de qué se trataba (por ejemplo yoga, osteopatía, acupuntura, campos electromagnéticos, etc.) En ambos apartados, había un campo libre para poder hacer cualquier aclaración. El último ítem del cuestionario solicitaba un número de teléfono para que, en caso de autorización, el investigador pudiese ampliar la información acerca del tipo de MAC empleada.

Posteriormente, se recogieron datos clínicos de los pacientes mediante la plataforma de Historia Clínica Informatizada del Servicio Navarro de Salud:

- •

Diagnóstico oncológico (tipo de tumor, estadio y momento del diagnóstico).

- •

Número de líneas de tratamiento oncológico recibidas.

- •

Cirugía y/o Radioterapia como tratamiento del proceso.

Se empleó el programa IBM SPSS v22 de Windows para realizar el análisis estadístico. Se llevó a cabo un estudio descriptivo mediante análisis de frecuencias y proporciones (N°, %) para las variables cualitativas, y medidas de posición para las variables cuantitativas edad y tiempo de consumo de MAC.

Se analizaron los potenciales predictores de uso de MAC mediante regresión logística simple. Se estimaron OR crudas y su intervalo de confianza al 95%.

ResultadosParticipantesDurante las dos semanas de muestreo, 539 personas fueron citadas en el Hospital de Día de Oncología para recibir tratamiento intravenoso. No se administró a 58 de ellas (10,8%), de modo que no accedieron a las salas en las que se estaba realizando el estudio, y a 108 personas no se les pudo localizar. Por lo tanto, el estudio se propuso a un total de 373 pacientes.

Hubo 53 personas que libremente decidieron no ser incluidas y otras 4 cumplían criterios de exclusión, debido a la imposibilidad de comprensión del cuestionario por desconocimiento del idioma en tres pacientes y por diagnóstico psiquiátrico en otro caso.

La muestra de este estudio se compone de 316 personas, lo que representa el 84,7% de los pacientes a los que se les propuso. Fue necesario realizar llamadas telefónicas para ampliar la información en 12 (3,8%) casos.

Características sociodemográficas y clínicasLas características sociodemográficas y clínicas de los pacientes se presentan en la Tabla 1.

Características sociodemográficas y clínicas de los pacientes

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sexo | ||

| Mujer | 173 | 54,7 |

| Lugar de residencia | ||

| Urbano | 166 | 52,5 |

| Rural | 150 | 47,5 |

| Estado civil | ||

| Soltero/a | 47 | 14,9 |

| Casado/a | 228 | 72,2 |

| Pareja de hecho | 9 | 2,8 |

| Divorciado/a | 10 | 3,2 |

| Viudo/a | 21 | 6,6 |

| Desconocido | 1 | 0,3 |

| Edad | ||

| ≤ 55 años | 94 | 29,7 |

| > 55 años | 222 | 70,3 |

| Nivel educativo | ||

| Sin estudios o básicos | 144 | 45,6 |

| Estudios Medios* | 122 | 38,6 |

| Estudios Superiores† | 50 | 15,8 |

| Tipo de cáncer | ||

| Mama | 102 | 32,3 |

| Colorrectal | 80 | 25,3 |

| Pulmón | 44 | 13,9 |

| Ginecológico | 20 | 6,3 |

| Cabeza-cuello | 15 | 4,7 |

| Gástrico | 11 | 3,5 |

| Páncreas | 10 | 3,2 |

| Otros‡ | 32 | 10,2 |

| Desconocido | 2 | 0,6 |

| Estadio enfermedad§ | ||

| I | 34 | 10,8 |

| II | 42 | 13,3 |

| III | 37 | 11,7 |

| IV | 202 | 63,9 |

| Desconocido | 1 | 0,3 |

| N° líneas tratamiento|| | 152 | 48,1 |

| 2-3 | 115 | 36,4 |

| ≥ 4 | 48 | 15,2 |

| Desconocido | 1 | 0,3 |

| Total | 316 | 100 |

Un total de 173 mujeres (54,7%) participaron en el estudio, y la edad media de los pacientes fue 61 años (24-85). Cerca de la mitad vivía en zona rural y casi tres cuartas partes de la población estaban casados. El 16% poseía titulación Universitaria.

El diagnóstico oncológico más frecuente fue cáncer de mama (32,3%), seguido de colorrectal y pulmón. La mediana de tiempo transcurrido desde el diagnóstico de la enfermedad fue 12 meses (rango 0-266 meses). Un total de 222 pacientes (70%) habían sido operados para tratar su tumor, y 138 (44%) habían recibido radioterapia. Hubo 10 (3,2%) pacientes que participaban en ensayos clínicos en el momento de su inclusión en el estudio.

Uso de MACEl uso simultáneo de MAC y el tratamiento convencional con quimioterapia fue referido por 102 pacientes (32,3%).

El 89% de las personas que empleaban MAC tomaban oralmente algún preparado. Los tipos de productos ingeridos con más frecuencia fueron plantas (n=60, 66%), seguido de terapias naturales (n=35, 38,5%), vitaminas/minerales (n=32, 35,2%) y homeopatía (n=16, 17,6%), respectivamente.

Se contabilizaron 51 plantas diferentes. El 11,7% de los pacientes que tomaban plantas empleaba cúrcuma, que fue la más frecuente seguido de uña de gato (8,3%), regaliz (8,3%), tomillo (8,3%), cardo mariano (6,7%), melisa (6,7%) y equinácea (5%). En el caso de terapias naturales, se contabilizaron 33 diferentes, siendo las más comunes hongos terapéuticos procedentes de la medicina tradicional china (14,3%), lactobacillus (14,3%), jalea real (11,4%), propóleo (11,4%), algas como spirulina y blue-green (8,6%), sacharomyces (8,6%), rábano (5,7%), ajo negro (5,7%) y jengibre (5,7%). De los pacientes que empleaban suplementos vitamínicos, el 50% usaba vitamina C, seguido de vitaminas del grupo B (31,3%) y vitamina E (18,8%). En cuanto a sales minerales, el zinc era empleado por el 21,9% de los pacientes que las tomaban, seguido de magnesio (15,6%), bicarbonato (9,5%) y cobre (9,4%). Los productos homeopáticos más comunes fueron el Suplemento Mineral Milagroso (MMS), consistente en clorito sódico, cicuta y carcinosinum, que era utilizado por el 43,8% que usaba homeopatía, y las Sales de Schussler (31,3%).

Del total de pacientes que afirmaron utilizar MAC, 37 (36,3%) practicaban alguna terapia relacionada con la “medicina de la mente y el cuerpo”, “prácticas de manipulación y basadas en el cuerpo” y/o “medicina sobre energía”. Entre éstas prácticas predominaron el yoga, reiki, aplicación de campos electromagnéticos, baños de agua con sal, acupuntura, hiperter- mia y ejercicios de relajación.

El 81,4% de los pacientes que empleaban MAC había comenzado a utilizarla tras el diagnóstico de la enfermedad (Tabla 2), siendo la mediana de tiempo de uso de 4,5 meses (0-180 meses).

Respuestas relativas al uso de Medicina Complementaria

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Momento de inicio (n=102) | ||

| Antes de enfermedad | 16 | 15,6 |

| A raíz de enfermedad | 83 | 81,4 |

| NS/NC | 3 | 3 |

| Fuentes de información* | ||

| Televisión | 0 | 0 |

| Revistas | 2 | 2 |

| Radio | 1 | 1 |

| Internet | 9 | 8,8 |

| Familia/amigos | 70 | 68,6 |

| Profesionales sanitarios† | 8 | 7,8 |

| Otros | 19 | 18,6 |

| NS/NC | 7 | 6, 9 |

| Resultado percibido (n=102) | ||

| Ninguno | 27 | 26,5 |

| Mejoría | 66 | 64,7 |

| Efectos adversos | 1 | 1 |

| NS/NC | 8 | 7,8 |

Abreviaturas: NS/NC, no sabe o no contesta.

El principal modo en el que conocieron la existencia de MAC (Tabla 2), fue través de familiares o amigos. Hubo 4 pacientes que indicaron conocer los productos a través de un Homeópata y 3 a través de Herboristería.

En relación a los resultados percibidos acerca de la MAC (Tabla 2), el 64,7% de las personas que la utilizaban afirmaron experimentar algún tipo de beneficio con la misma. Se indicó un efecto adverso, descrito como acidez de estómago tras la ingesta de un preparado comercial de equinácea y uña de gato. Analizando exclusivamente los pacientes que comenzaron a usar MAC a raíz del diagnóstico oncológico, 52 (63%) referían que la MAC les estaba ayudando en algún aspecto: 24 (29%) consideraban que les aportaba fortaleza física y psíquica, 20 (24,1%) que les ayudaba a paliar los efectos secundarios del tratamiento, 14 (16,9%) que estaba contribuyendo a fortalecer el sistema inmunitario y 2 (2,4%) a luchar contra el cáncer.

Características que influyen en el empleo de MACEn la Tabla 3 se describen los potenciales predictores de uso de MAC teniendo en cuenta las características sociodemográficas y clínicas estudiadas. El sexo femenino se asoció de manera positiva con el uso de MAC, de manera que se estimó que las mujeres tenían 1,72 veces (IC95% 1,06-2,80; p=0,028) más riesgo de usar MAC que los hombres. La edad también mostró diferencias significativas en el uso de MAC. Teniendo en cuenta la edad como variable continua, ésta mostró un consumo decreciente de MAC por año cumplido (OR: 0,96 IC95% 0,94-0,98; p<0,001). El riesgo de empleo de MAC fue doble en los pacientes con estudios medios respecto a los que carecían de estudios o tenían estudios básicos (IC95% 1,19-3,38; p=0,009).

Características socio-demográficas y clínicas influyentes en el uso de MAC

| Variable | Consumo MAC | OR (IC 95%)* | P valor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO n (%) | SI n (%) | |||

| Sexo | ||||

| Varón | 106 (74,1) | 37 (25,9) | (referencia) | |

| Mujer | 108 (62,4) | 65 (37,6) | 1,72 (1,06-2,80) | 0,028 |

| Edad | ||||

| < 55 años | 50 (53,2) | 44 (46,8) | (referencia) | |

| > 55 años | 164 (73,9) | 58 (26,1) | 0,40 (0,24-0,66) | <0,001 |

| Lugar de residencia | ||||

| Urbano | 117 (70,5) | 49 (29,5) | (referencia) | |

| Rural | 97 (64,7) | 53 (35,3) | 1,31 (0,81-2,09) | 0,270 |

| Estado civil† | ||||

| Soltero/a | 36 (76,6) | 11 (23,4) | (referencia) | |

| Casado/a | 148 (64,9) | 80 (35,1) | 1,77 (0,85-3,67) | 0,125 |

| Pareja de hecho | 5 (55,6) | 4 (44,4) | 2,62 (0,60-11,48) | 0,202 |

| Divorciado/a | 7 (70,0) | 3 (30,0) | 1,40 (0,31-6,36) | 0,661 |

| Viudo/a | 17 (81,0) | 4 (19,0) | 0,77 (0,21-2,77) | 0,689 |

| Nivel educativo | ||||

| Sin estudios o básicos | 107 (74,3) | 37 (25,7) | (referencia) | |

| Estudios medios‡ | 72 (59,0) | 50 (41,0) | 2,01 (1,19-3,38) | 0,009 |

| Estudios superiores§ | 35 (70,0) | 15 (30,0) | 1,24 (0,61-2,52) | 0,554 |

| Tipo de tumor | ||||

| Mama | 68 (66,7) | 34 (33,3) | (referencia) | |

| Colorrectal | 55 (68,8) | 25 (31,2) | 0,91 (0,49-1,70) | 0,766 |

| Pulmón | 31 (70,5) | 13 (29,5) | 0,84 (0,39-1,81) | 0,653 |

| Resto | 60 (66,7) | 30 (33,3) | 1,00 (0,55-1,82) | 1,000 |

| Tiempo diagnóstico | ||||

| < 12 meses | 107 (65,6) | 56 (34,4) | (referencia) | |

| 13-35 meses | 45 (62,5) | 27 (37,5) | 1,15 (0,64-2,04) | 0,642 |

| > 36 meses | 62 (76,5) | 19 (23,5) | 0,59 (0,32-1,08) | 0,084 |

| Estadio oncológico | ||||

| IV | 135 (66,8) | 67 (33,2) | (referencia) | |

| Resto | 79 (69,9) | 34 (30,1) | 0,87 (0,53-1,43) | 0,574 |

| Cirugía† | ||||

| No | 68 (73,1) | 25 (26,9) | (referencia) | |

| Sí | 146 (65,8) | 76 (34,2) | 1,42 (0,83-2,42) | 0,203 |

| Radioterapia† | ||||

| No | 114 (64,4) | 63 (35,6) | (referencia) | |

| Sí | 100 (72,5) | 38 (27,5) | 0,69 (0,42-1,12) | 0,129 |

| N° líneas tratamiento | ||||

| 1 línea | 104 (68,4) | 48 (31,6) | (referencia) | |

| > 1 línea | 110 (67,1) | 54 (32,9) | 1,06 (0,66-1,71) | 0,798 |

Abreviaturas: MAC, medicina alternativa y complementaria.

La mitad de los pacientes que formaban parte de ensayos clínicos afirmaron utilizar MAC en el momento del estudio, sin encontrar diferencias estadísticamente significativas en el uso de MAC respecto a los pacientes que no participaban en ensayos (OR: 2,16 IC95% 0,61-7,62).

DiscusiónSe dispone de poca información acerca del uso de MAC entre las personas diagnosticadas de cáncer en España. El trabajo actual aporta una evidencia inicial acerca de la frecuencia de empleo de éstas medicinas complementarias y los tipos de prácticas utilizadas. En concreto, lo hace en aquellos pacientes que reciben tratamiento intravenoso, en los que puede existir riesgo de interacción entre la MAC y el mismo.

La prevalencia de consumo de MAC en esta población fue ligeramente superior a la referida para la población global española (29,8%), en el único estudio multicéntrico europeo sobre MAC en pacientes oncológicos que existe hasta la actualidad6. Son datos consistentes con resultados previos de estudios realizados sobre MAC en el campo de la oncología. En el año 1998 se llevó a cabo una revisión sistemática de 26 trabajos con pacientes oncológicos en 13 países, y mostró una media de consumo del 31%14. Sin embargo, debido a la creciente popularidad de la MAC se podía esperar obtener tasas de consumo superiores en este trabajo. De hecho, en población norteamericana se han documentado cifras de empleo de MAC del 64-90% en pacientes oncológicos4,5, y en países asiáticos son cercanas al 50%15,16,17. Estas elevadas cifras de prevalencia pueden relacionarse con la diversidad racial y cultural presente en estos países, y verse influenciadas tanto por las prácticas de MAC occidentales como orientales. A nivel europeo, también se han encontrado cifras elevadas de uso de MAC, entre el 45-51%9,18,19. Sin embargo, en un estudio italiano que preguntaba exclusivamente por el uso actual de MAC, al igual que en nuestro caso, la cifra descendía al 14%20.

La comparación directa de los resultados de este trabajo con estudios previos debe hacerse con precaución, ya que pueden existir diferencias en el tipo y tamaño de muestra, metodológicas, y conceptuales (definición y tipo de terapias consideradas como MAC). En este estudio no se incluyeron a los pacientes oncológicos que no estaban siendo tratados ni a los que seguían tratamiento con quimioterapia oral, por motivos de limitación de personal y temporal. No se incluyeron como MAC las dietas especiales ni zumos especiales contemplados por otros autores21,22, considerándose sólo aquellos alimentos formulados comercialmente como cápsulas, comprimidos, etc. o productos de la medicina tradicional china15. Tampoco se tuvieron en cuenta los batidos hiperproteicos, ya que forman parte del cuidado médico habitual de estos pacientes. En cuanto a las plantas consideradas, cabe señalar que no se definieron como MAC el té blanco, té verde, té rojo y té negro, ante la dificultad que suponía identificar si su uso tenía una intención terapéutica. Esto se diferencia de otros estudios, en los que se documenta el uso de té verde como MAC4,5,6,15. Estas limitaciones en la definición de MAC, y el hecho de evaluar exclusivamente su uso en el momento actual, son posibles causas de la menor prevalencia encontrada en el presente estudio.

Los tipos de MAC más utilizados en la muestra suponían un consumo oral de productos, frente a la realización de prácticas relacionadas con el cuerpo o la mente. Las sustancias más empleadas fueron plantas, terapias naturales y vitaminas/minerales, como ya se ha documentado en otros estudios11,19,23. Este aspecto refleja el atractivo que tienen las terapias y remedios “naturales” para los pacientes, pero son precisamente estas sustancias las que entrañan mayor riesgo6. De hecho, han sido identificadas interacciones farmacocinéticas entre ciertas hierbas y productos naturales con la quimioterapia: el ajo, gingseng, equinácea y la soja son inhibidores del CYP450 en estudios preclínicos24-25, por lo que pueden disminuir la eliminación de los fármacos citostáticos e incrementar como consecuencia su toxicidad. Precisamente el ajo y la equinácea fueron productos utilizados por los pacientes del estudio. Otras sustancias utilizadas y que interaccionan con fármacos quimioterápicos son: regaliz, reishi, rábano y jengibre26. La suplementación vitamínica más frecuente fue la vitamina C, para la que se han descrito interacciones con agentes antineoplásicos como metotrexa- to o imatinib27.

La mayoría de pacientes (81%) comenzaron la MAC tras el diagnóstico oncológico. Sin embargo, el boca a boca de familiares y amigos parece ser la fuente más importante, al igual que en otros estudios6-7, siendo la consulta al profesional sanitario poco frecuente. Se hace patente la necesidad de concienciación y formación de los profesionales sanitarios en el uso de MAC, para que puedan llegar a ser el referente en el tratamiento integral del paciente. En este aspecto el farmacéutico hospitalario puede desarrollar una labor importante, especialmente en el análisis de interacciones potenciales entre el tratamiento convencional y complementario. Podría ser de utilidad la implantación de sistemas de alerta que contemplen estos productos en los programas informáticos de validación y dispensación farmacéutica.

Una cuarta parte de los pacientes que usaban MAC afirmaba no sentir ninguna mejoría con la misma. A pesar de ello, seguían empleándola; quizá el concepto de “esperanza” pueda ser fundamental en la razón que contribuya al uso de MAC6. Los aspectos beneficiosos más indicados por los pacientes guardan relación con las principales razones que motivan a usar MAC en otros estudios: otorgar buen estado de salud general, bienestar físico y emocional y fortalecer el sistema inmunitario6-7,28. A pesar de que en el cuestionario se preguntaba específicamente por los resultados obtenidos con la MAC, la mejoría percibida por los pacientes podría estar influenciada por los efectos del tratamiento, debido a que la MAC se empleaba a la vez que la quimioterapia.

Hubo tres variables predictoras del uso de MAC: ser mujer, ser joven y tener estudios medios. Las dos primeras se han identificado en otros trabajos6,29. Sin embargo, también se ha asociado el mayor empleo de MAC a pacientes con estudios superiores6,8 y a estadios avanzados de la enfermedad30.

En este estudio pudo haber ciertas limitaciones. A los pacientes se les solicitaba indicar en el cuestionario el tipo de MAC que empleaban, clasificándolo en una determinada categoría. Puesto que es frecuente que los pacientes utilicen más de un tipo de MAC, puede haber sesgos en relación al recuerdo y al conocimiento del tipo de MAC. Con la intención de minimizarlo, se llevaron a cabo llamadas telefónicas a pacientes que no eran capaces de recordarlo en el momento de la entrevista. Hubiera sido interesante hacer una visita de seguimiento presencial para ver físicamente los productos utilizados y poder categorizarlos. Debido a un problema temporal, no fue posible hacerlo en este estudio. Por otro lado, la participación de dos investigadores en las entrevistas a pacientes implica que pueda haber sesgo del entrevistador, debido a la influencia que pueda tener el diferente modo de comunicación oral y corporal sobre las respuestas del paciente. Para minimizarlo ambos entrevistadores participaron en el diseño del cuestionario, y consensuaron criterios en la definición de MAC y su clasificación.

Un número importante de pacientes en este estudio usaron MAC al mismo tiempo que el tratamiento médico habitual. Debido a que la MAC se basaba fundamentalmente en una ingesta oral de sustancias, existe un riesgo potencial de interacción con la quimioterapia. Al no ser un objetivo del presente estudio, desconocemos la magnitud de este problema. Consideramos necesario concienciar a los profesionales sanitarios sobre la importancia de indagar sobre el empleo de MAC entre los pacientes y poder aconsejarles sobre ello. De acuerdo a este estudio, las mujeres, los jóvenes y las personas con estudios medios son los que más emplean MAC de manera estadísticamente significativa, lo cual puede resultar de ayuda para identificar al potencial usuario de la misma. Sería interesante realizar futuros trabajos para estudiar el uso de MAC en grupos de pacientes con un tipo de cáncer concreto, e indagar en las posibles interacciones entre la MAC y la quimioterapia.

Este es el primer estudio realizado en España, según nuestro conocimiento, que analiza la frecuencia de uso de medicina complementaria entre los pacientes oncológicos que reciben tratamiento médico con quimioterapia. Se ha documentado un uso frecuente de medicina alternativa y complementaria entre estos pacientes, pero la mayoría de la información procede de países norteamericanos. En este trabajo se observa que un tercio de los pacientes que acuden a Hospital de Día a recibir quimioterapia intravenosa emplean simultáneamente otro tipo de prácticas, en su mayoría a base de ingesta de sustancias (89%), sobre todo plantas y terapias naturales. La diversidad de este tipo de productos fue importante, por el elevado contenido de componentes diferentes en un mismo preparado. Este aspecto contrasta con la escasa consulta al profesional sanitario acerca de la medicina complementaria, ya que solo el 8% de los pacientes refirió haber obtenido información a partir del mismo. Los factores que se asociaron al uso de medicina complementaria fueron el sexo (mujer), la edad y el nivel educativo (estudios medios).

Independientemente del posicionamiento de los profesionales sanitarios en el ámbito de la medicina complementaria, este trabajo demuestra que los pacientes la emplean, ante el impacto físico-emocional que conlleva el diagnóstico y tratamiento oncológico. Debido a la elevada prevalencia de estas prácticas y a la escasa consulta observada al profesional sanitario, es importante la formación en este ámbito, para que el profesional pueda llegar a ser un referente en el consejo sobre la efectividad y contraindicación de ciertos usos de medicina complementaria. El papel del farmacéutico hospitalario es relevante en la entrevista al paciente y la revisión de las posibles interacciones entre las sustancias empleadas y la quimioterapia, con el fin de garantizar su seguridad y eficacia.

- Inicio

- Todos los contenidos

- Publique su artículo

- Acerca de la revista

- Métricas