To report our experience with Telemedicine projects: a Telepharmacy Hospital Pharmacy/Primary Care Pharmacy Coordination Program and a Hospital Pharmacy/Primary Care Pharmacy Electronic Cross-consultation Program. Results are reported in terms of medication adherence, perceived quality and satisfaction, and economic impact.

MethodA) Telepharmacy Hospital Pharmacy/Primary Care Pharmacy Coordination Program: Phases of development: 1) Creation of a work group; 2) definition of patient inclusion criteria; 3) selection of medicines; 4) integration of hospital and primary care pharmaceutical care; 5) setting up of facilities in primary care; 6) logistics design; 7) creation of the Telemedicine system; 8) provision of training to primary care pharmacists; 9) establishment of a pharmaceutical care protocol; 10) obtaining patient informed consent. Medication adherence was evaluated using dispensing records. Results were assessed based on a quality questionnaire. Pharmcicist evaluation was performed using a satisfaction questionnaire. The economic impact of the programs was assessed from patient's perspective from the estimated 1-year avoided direct costs of traveling from home to the hospital. B) Webbased cross-consultation system: mining was performed of web data from August 2018-June 2019. Analyzed items: hospital pharmacoterapeutic area, reasons, and results of consultation in primary and hospital care.

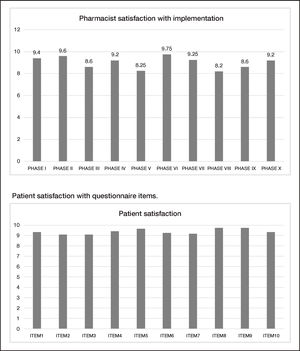

ResultsA) Telepharmacy Hospital Pharmacy / Primary Care Pharmacy Coordination Program: sample: 51 patients, 58% male. Mean age 62.8 ± 18.0 years. 83.0% were pensioners; 69% were involved in an enteral nutrition program. Baseline and post-intervention medication adherence, 95.82 ± 8.03 vs 85.23 ± 23.02 (p = 0.007). Patients took 3.3 ± 1.4 hours to travel to the hospital; all patients assumed traveling costs. Average avoided cost per patient per year, €76.08 ± 38.77. Average score on the satisfaction questionnaire, 9.4 ± 1.3 over 10. The most valued items were work/family reconciliation and cost savings. No items were identified as negative in the program. Pharmacist satisfaction was 9.0 ± 1.2 over 10. B) Electronic cross-consultation program: 458 consultations, 190 from secondary to primary care, and 268 from primary to secondary care.

ConclusionsThe Telemedicine programs enabled coordination of drug therapy monitoring between the hospital and the primary care pharmacy. Patients and professionals reported a high level of satisfaction with the Telepharmacy Hospital Pharmacy/Primary Care Pharmacy Coordination Program, which had a very positive economic impact. Finally, the two Telepharmacy programs integrate humanization strategies.

Analizar estrategias de Telemedicina y colaboración entre atención primaria y atención hospitalaria: programa de Telefarmacia de Coordinación entre los Equipos Asistenciales de Farmacia Hospitalaria y Atención Primaria y la plataforma e-interconsulta. Describir la implantación del programa Telefarmacia de Coordinación entre los Equipos Asistenciales de Farmacia Hospitalaria y Atención Primaria y evaluar los resultados sobre adherencia terapéutica, calidad percibida y satisfacción y económicos, así como las e-interconsultas realizadas entre atención hospitalaria y atención primaria.

MétodoA) Telefarmacia de Coordinación entre los Equipos Asistenciales de Farmacia Hospitalaria y Atención Primaria: fases de implantación: 1) creación del grupo de trabajo; 2) establecimiento de criterios de inclusión de pacientes; 3) selección de medicamentos; 4) integración de la documentación de la atención farmacéutica; 5) acondicionamiento de la consulta de atención primaria; 6) diseño logístico; 7) creación del sistema de Telemedicina; 8) formación a farmacéuticos de atención primaria; 9) protocolización de la atención farmacéutica; 10) información al paciente y consentimiento informado. La adherencia se evaluó por registro de dispensaciones. Evaluación de los resultados mediante cuestionario de calidad percibida. Evaluación por farmacéuticos mediante encuesta de satisfacción. Análisis del impacto económico según costes directos estimados de los desplazamientos evitados desde el domicilio hasta el hospital durante un año. B) Plataforma e-interconsulta: explotación de los datos de la plataforma web de agosto de 2018 a junio de 2019. Se analizó: área farmacoterapéutica en atención hospitalaria, motivos y resultados de las mismas en atención primaria y atención hospitalaria.

ResultadosA) Telefarmacia de Coordinación entre los Equipos Asistenciales de Farmacia Hospitalaria y Atención Primaria: 51 pacientes incluidos, 58% varones. 62,8 ± 18,0 años de media de edad. 83,0% pensionistas; 69% adscritos al programa de nutrición enteral domiciliaria. Adherencia previa y tras la implantación del programa: 95,82 ± 8,03 versus 85,23 ± 23,02 (p = 0,007). Los pacientes emplearon una media de 3,3 ± 1,4 horas en el desplazamiento al servicio de farmacia del hospital; el 100% asumió el gasto de los desplazamientos. Coste medio evitado por paciente/año: 76,08 ± 38,77 €. Media de valoración de la encuesta de satisfacción: 9,4 ± 1,3 sobre 10. Resultado de la encuesta de satisfacción a farmacéuticos: 9,0 ± 1,2. B) Plataforma e-interconsulta: 458 consultas realizadas: 190 desde atención hospitalaria a atención primaria, y 268 desde atención primaria a atención hospitalaria.

ConclusionesEstos programas de Telemedicina permiten un seguimiento farmacoterapéutico coordinado del paciente externo entre farmacia hospitalaria y atención primaria. El programa Telefarmacia de Coordinación entre los Equipos Asistenciales de Farmacia Hospitalaria y Atención Primaria cuenta con una alta valoración de calidad percibida por pacientes y farmacéuticos y un elevado impacto económico para el paciente. Ambos proyectos integran estrategias de humanización que facilitan proporcionar una atención farmacéutica más cercana al paciente, evitándole desplazamientos innecesarios al hospital.

Healthcare has traditionally been structured into two levels: Primary Care (PC) and Secondary Care (SC). However, this structure has evolved towards a new integrated model that pursues the provision of quality patient-centered healthcare. This new model is focused on the promotion of healthy habits and disease prevention1,2. This change of model is supported by scientific societies such as the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH) in its 2020 plan3. The Servizo Galego de Saúde (SERGAS) 2020 Strategy4 focused on new patient profiles, namely, elderly, polymedicated patients with chronic diseases, who are empowered and increasingly involved in the healthcare process. Still, poor coordination between professionals at different levels of healthcare negatively affects patients in the form of drug-related problems, and hindering patient access to drug therapies2,5.

The SEFH recently published a position paper on Telepharmacy6, where it is considered a complementary tool for hospital pharmacy (HP) care. Thus, Telepharmacy has four scopes of application: drug therapy monitoring; patient/caregiver education and training; intra- and extra-hospital multidisciplinary coordination; and home dispensation and informed delivery of medicines. Telepharmacy improves coordination between different levels of healthcare thereby providing integrated HP care to patients. Our Hospital Pharmacy Service (HPS) has launched a set of integrated service and communication initiatives, the most relevant being the Hospital Pharmacy/PC Pharmacy electronic cross-consultation platform7,8. This platform provides coordinated pharmaceutical care to patients using hospital prescriptions. However, a PC/SC communication channel was not available in relation to outpatients using hospital prescriptions. A Telepharmacy Hospital Pharmacy (HP)/Primary Care (PC) Pharmacy Coordination Program (THP-PCP) was designed as a humanization strategy. The aim of this program was to facilitate outpatient access to prescriptions dispensed at the hospital pharmacy. This program also aimed at ensuring the provision of quality pharmacy care, with shared responsibility between the two levels of healthcare.

The objective of this study was to analyze the two Telepharmacy and PC/SC coordination schemes, and describe the phases of implementation of the THP-PCP coordination program. Other objectives include assessing results in terms of therapeutic adherence, perceived quality, and cost-effectiveness, and evaluating PC/SC teleconsultations during the same period.

MethodsThe Telepharmacy Hospital Pharmacy (HP)/Primary Care Pharmacy (PCP) Coordination Program (THP-PCP) developed in our Hospital Pharmacy Service was based on two strategies:

- A)

A teleconsultation platform, which is an electronic communication system that was incorporated into our health area in 2015, as described elsewhere7,8. This system serves as a HP/PCP communication channel aimed at providing quality pharmacy care to outpatients, especially during transition of care, to reduce drug-related issues.

- B)

The THP-PCP coordination project was a healthcare quality improvement initiative proposed by the HPS to the Node of Healthcare Innovation. This tool was designed to facilitate innovation in healthcare. The initial project consisted of a pilot six-month project that was implemented in three primary care centers. The purpose was to monitor and evaluate the implementation of the project prior to subsequent extension to other centers. The pilot project ran from August 2018 to January 2019. In this program, patients collected their hospital prescriptions at their primary care center.

The phases of implementation included:

IWorking GroupA multidisciplinary working group (WG) was formed to establish patient inclusion criteria; included prescriptions; action protocols; pathways; and control and evaluation mechanisms. The WG was composed of four hospital pharmacists, three PC pharmacists, the Director of Outpatient Processes, and the Director of XXIAC Support.

IIInclusion and exclusion criteriaInclusion criteria:

- •

Adults.

- •

Outpatient follow-up in the HPS during the last 6 months minimum.

- •

Clinical stability.

- •

100% treatment adherence at physician's and pharmacist's judgment, based on dispensing records.

- •

Limited access to treatment due to functional dependency.

- •

Patients involved in SERGAS medication programs: Home Enteral Nutrition (HEN) or arthropathies treated with parenteral biological agents.

Exclusion criteria:

- •

Changes of treatment due to lack of efficacy or occurrence of adverse events, until the reason for change is resolved.

- •

Failure to attend appointments in the last year that were not rescheduled.

- •

Concomitant treatment with other hospital prescriptions.

- •

Having hospital appointments during the dispensation period.

Prescription and interventions were selected on the basis of their simplicity of use, safety and stability: etanercept (drug of reference and two biosimilar drugs, in preloaded syringe and pen injector); fluid thickeners; and protein supplementation.

Likewise, minimum and maximum stocks were established in each PC center.

IVInformation System IntegrationPC pharmacists were granted access to the PEA Silicon program and permission to modify and record treatment regimens and medicine dispensations. In addition, a specific section was incorporated into the PC electronic medical history (Ianus) to document pharmaceutical care provided by PC pharmacists. The outpatient HPS was granted access to consult the clinical course of patients. Given that a single clinical course was not possible, follow-up was performed in independent episodes by secondary and primary care.

VEvaluation, provision of equipment for the PC pharmacy, and logisticsMedicine storage facilities in PC were evaluated and fitted to optimize storage conditions. Moist and temperature control systems were installed.

In terms of logistics, specific drug shipping and delivery days were established, since a transport was already operating.

VIDesign of the pharmaceutical ordering platform of the Primary Care centerAn information system was designed for drug orders and returns and incorporated to the HP/PCP Collaborative Web portal. This portal was already in use on the tele-consultation platform7, and was selected due to its versatility, easy-access, security, and convenience.

A web-based Microsoft-Sharepoint prescription order form was designed. An alert system was incorporated to the electronic mail of participants, for the HPS staff to receive notifications about new orders. Participants could check order status and records (Figure 1). The HPS performed regular shipping of medication to primary care centers.

VIIPCP trainingPrior to initiation of the pilot project, two 2-h training sessions were conducted: a training activity on pharmaceutical care in HEN patients, and another for patients with arthropathies receiving biological agents. Sessions were conducted by the heads of the HP of each area, including: disease, drug therapy, pharmaceutical care, patient referral, and documentation.

VIIIEstablishment of a protocol and pharmaceutical care documentationIn line with the HPS protocol, the clinical interview in PC included a treatment adherence assessment; clinical efficacy endpoints; adverse event detection and prevention; revision of drug-drug interactions; and general drug information.

Patients could contact the HPS pharmacist or withdraw from the program at any time. Patients were offered to voluntarily participate in the home dispensing program available in the HPS, described elsewhere9.

IXPatient information. Informed consentAll patients signed an informed consent for prior to inclusion in the program. Approval from the Ethics Committee was not considered necessary.

XProgram operating pathwayPatient inclusion was performed by the HPS following the pathway described below:

- 1.

Detection of a candidate that meets inclusion criteria.

- 2.

The HPS invites the patient to participate and the program and sign informed consent.

- 3.

Patient inclusion in the THP-PCP program is recorded on the clinical course documented by the outpatient HPS.

- 4.

The patient makes an appointment with the pharmacy of the primary care center.

- 5.

A pharmacy consultation is performed and prescriptions are dispensed by the PC pharmacist.

- 6.

The pharmaceutical care provided is recorded on the clinical history of the patient. Next appointment is scheduled.

- 7.

A request is submitted to the HPS to restock the medication dispensed.

- 8.

Drug therapy monitoring is coordinated between the HPS and the PCP. Cross-consultation is available on the e-consultation platform, added to the traditional communication channels (e-mail or phone).

- 9.

The patient attends at least a yearly appointment with the HPS, which will coincide with a face-to-face appointment with the specialist.

An assessment of the results of electronic e-consultations between the HP and the PCP is performed. Data from August 2018 to June 2019 available on the web-based platform is exploited. Electronic cross-consultations from the PCP to the HP were classified by pharmacotherapeutic area, whereas cross-consultations from the HP to the PCP were classified by primary care center. Electronic cross-consultations were analyzed by pharmacotherapeutic area. An analysis of reasons of consultation and results in the HP and the PCP was performed.

Baseline treatment adherence prior to the implementation of the THP-PCP program was assessed on the basis of the HPS dispensing records of the last 6 months. Treatment adherence after inclusion in the program was evaluated considering PC dispensing records 6 months after inclusion.

Healthcare professionals and patients were asked to evaluate the THP-PCP project to get a picture of the limitations and advantages of the program and assess perceived quality. Pharmacists completed a satisfaction questionnaire that assessed the 10 phases of implementation of the project. The questionnaire included three free-text questions, where respondents described the most and least valued aspects of the program and limitations to the implementation of the program in other primary care centers, patients, and prescriptions. Patients completed a satisfaction questionnaire (Figure 2) that included: baseline demographic characteristics; occupational status; means of transport; travel time and cost; participating center; satisfaction with logistics and pharmacy care; advantages and disadvantages of the program; and opportunity to withdraw from the program.

The cost-effectiveness of the THP-PCP program was assessed by analyzing the estimated direct costs of avoided travels from home to the hospital. Distance from home to the hospital was measured in km. The cost per km was set at €0.19 according to data provided by the Service of Internal Organization and Security of the hospital. Costs were estimated considering six round trips per year, since dispensations are performed on a bimonthly basis. Indirect costs or waiting times prior to consultation, or travels from home to the primary care center were not considered.

ResultsA total of 458 e-consultations were carried out, of which 190 were made from SC to PC, and 268 from PC to SC. Notably, in the area of secondary care, half of e-consultations were related to the need for monitoring hospital prescriptions in PC patients. In the area of PC, the main reason for e-consultation to secondary care were issues related to prescription validation. Breakdown of e-consultations by reason, result, and pharmacotherapeutic area are detailed in Table 1.

Results e-consultations carried out between SC/PC.

| e-consultations from SC to PC n° = 190 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reason for consultation | n° | Results | n° |

| Pharmacotherapy Monotoring need in PCP | 108 | Pharmacotherapy Monotoring in PCP | 82 |

| Medication reconciliation | 32 | Clarify hospital prescription | 39 |

| Approval of prescriptions | 14 | Medication reconciliation | 48 |

| Medications interaction | 13 | Others | 21 |

| Off label medication | 8 | ||

| Pharmacoterapy Adherence | 9 | ||

| Others | 6 | ||

| e-consultations from PC to SC n° = 268 | |||

| Reason for consultation | n° | Pharmacotherapeutic area | n° | Results | n° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approval of prescriptions | 122 | Cardiology and Vascular surgery | 50 | Clarify hospital prescription | 140 |

| Medication reconciliation | 51 | Neurology | 55 | Process report/Healthy homologation of prescriptions | 43 |

| Wrong doses | 40 | Immunosuppression/trasplant | 44 | Medication reconciliation | 27 |

| Off label medication | 39 | Oncology/Hematology | 38 | Process off label medication | 16 |

| Others | 16 | Pediatrics | 19 | Doses change | 13 |

| Internal Medicine | 17 | Doses change | 29 | ||

| Ginecology | 13 | ||||

| Others | 32 |

PC: Primary Care; SC: Secondary Care.

Fifty-one patients were included in the THP-PCP project, of which 58% were male. Mean age was 62.8 ± 18 years. Eighty-three percent were retired. 69% were involved in the HEN program.

Treatment adherence at baseline and after the program was 95.82 ± 8.03 vs 85.23 ± 23.02 (p = 0.007).

The level of satisfaction of the professionals involved was 9.0 ± 1.2. A breakdown of satisfaction is provided in Figure 3. The most valued aspects are the high level of patient satisfaction and the improved visibility of PC pharmacists. The least valued aspects were the lack of education among substitute PC pharmacists, the lack of legal validation of PC centers as hospital prescription dispensing units, and the added workload.

Mean patient perceived quality was 9.4 ± 1.3 over 10. Figure 3 shows scores by item. The most valued advantage by patients was work-life reconciliation and cost savings. Patients did not found any disadvantage.

With regard to the economic impact of the program, patients/caregivers devoted a mean of 3.3 ± 1.4 in their travels from home to the HPS. Travel costs were entirely assumed by the patients. Ninety percent of patients lived more than 70 km away from the hospital (range 26-73 km). Mean avoided cost per patient/year was €76.08 ± 38.77.

DiscussionAccess to medicines and healthcare professionals is a concern of patients, decision-makers, and healthcare professionals. The transition towards a more humanized healthcare system based on a patient-centered approach involves facilitating this access. In this context, aware of their crucial role, HPSs have developed different outpatient integrated humanization projects10,11. In the international sphere, a variety of similar strategies have been implemented12–18. These strategies are aimed at eliminating healthcare barriers and promoting the management of chronic patients19,20. Hospital pharmacy care has transitioned towards a continuum of patient-centered care. Thus, inter-level transition is critical to the quality and safety of drug therapies. Of special relevance are teleconsultation programs involving home dispensing and inter-hospital coordination9.

Telepharmacy programs such as the electronic cross-consultation platform and the THP-PCP coordination project, are aimed at facilitating patient access to drug therapies through coordinated dispensing by the HP and the PC pharmacy. These projects provide safe quality pharmaceutical care and promote co-responsibility for clinical outcomes. Additionally, Telepharmacy facilitates communication among healthcare professionals. In these projects, cutting-edge technologies enabled the integration of different levels of healthcare. The interoperativity of PC pharmacy and HP information systems was crucial for the development of these Telepharmacy programs.

The results obtained from electronic cross-consultations are consistent with previous studies7,8. Electronic cross-consultations from secondary care to PC were mostly related to the need for monitoring hospital prescriptions in PC. In contrast, cross-consultations from PC to SC were due to the prescription of recently marketed dugs (such as new oral anti-coagulant or anti-platelet agents) or the follow-up of transplant recipients or patients with onco-hematologic disease. In our opinion, the electronic cross-consultation platform emerges as a valid communication channel for different levels of healthcare.

In relation to treatment adherence in the THP-PCP project, statistically significant differences were observed, since patients included in the Telepharmacy program showed poorer treatment adherence. This is inconsistent with the results of previous studies, with patients involved in Telepharmacy programs exhibiting improved adherence (89%)21. However, it is worth mentioning that adherence was only determined on the basis of dispensing records, which is a significant limitation of this study, as other methods should have been used to support data from dispensing records. This difference is relevant and warrants further studies. Another cause could be that a high percentage of participants were involved in the HEN program, where adherence is generally very irregular.

The professionals involved in the THP-PCP project exhibited a high level of satisfaction. Their questionnaires will help us identify points of improvement and limitations to a potential generalization of the program. The electronic cross-consultation platform was not assessed and should be the focus of future research.

Education and training are crucial, and continuing education programs for PC pharmacists are necessary. The results of this study also highlight the relevance of documentation, which facilitates inter-level communication.

THP-PCP patients showed a high level of satisfaction, with a mean of 9.4 ± 1.3 over 10 points. HP patient satisfaction was 9.3 (according to satisfaction surveys carried out by the HPS in the previous years). According to the results obtained, this new system maintains high perceived quality in all the variables analyzed, including procedural and logistic variables (appointments, confidentiality, etc.), as well as pharmaceutical care variables (information provided by the pharmacist, time devoted to the patient, and courtesy). This is supported by the fact that only two patients preferred face-to-face HPS care, due to incompatibility with the working hours of the PC pharmacy. The most valued advantage by patients was work-life reconciliation and cost savings, and the totality of patients did not find any disadvantage in the program. High patient and professional satisfaction with the program is consistent with previous studies on Telepharmacy21. A limitation of this study is that patient-reported outcomes, or PROs, were not assessed. PROs provide information about patient health status, quality of life, functional status, and social factors. Thus, PROs facilitate the detection of problems, improves drug therapy monitoring, and facilitates patient/professional communication22,23. Another limitation is that patients were not involved in program design, which should be considered in future similar projects, as they are aimed at improved patient care.

With regard to the economic impact of the THP-PCP project, the results reveal that a high percentage of elderly patients spend 3.5 h traveling to the HPS on their private vehicles. It is important that these aspects are considered, since travel times to collect medication on a monthly or bimonthly basis lifelong affects work-family reconciliation. The cost of in-person pharmacy care is also an important aspect to be considered, since travel costs in Telepharmacy patients prior to inclusion in a home dispensation program reached €140/patient-year9, which exceeds the amount estimated in our study (€76). This difference is explained by the fact that a higher percentage of patients living more than 70 km from the HP were included in the previous study, whereas only 19% of our patients lived at that distance from the hospital. Patients highly valued the cost savings that Telepharmacy involves, which is in line with previous studies22. This opens a new avenue for future research to estimate the avoided costs in medicines and travels in patients involved in the electronic cross-consultation platform, as a result of improved inter-level communication.

Finally, these projects incorporate humanization strategies by which personalized pharmaceutical care is provided, sparing patients from unnecessary travels to the hospital. An avenue for future research is assessing the impact of these programs on clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, Telepharmacy programs improve coordination between different levels of healthcare, and facilitate patient access to their treatments and to healthcare professionals, resulting in an enhanced pharmacy care quality. These programs also ensure the continuity of drug therapy monitoring by favoring cooperation between primary and secondary care.

FundingNo funding.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank the Node of Innovation of the Xerencia de Xestión Integrada A Coruña.

Conflict of interestNo conflict of interest.

Contribution to the scientific literature:

This study describes the implementation, development, and results of a Telepharmacy hospital pharmacy/primary care coordination program. Experience with a web-based, inter-level, cross-consultation platform is also reported.

The Telepharmacy projects described may serve as a reference for other centers and be of interest for patients, healthcare professionals, and the healthcare system.