To analyse the presence of Good Humanisation Practices in the care of patients with rare diseases in Hospital Pharmacy Services and to identify the strengths and prevalent areas for improvement in the humanisation of healthcare.

MethodsAn online questionnaire structured in 2 parts was developed using Google Form®. The first one was designed to collect identifying data and the second one included questions related to compliance with the 61 standards of the Manual of Good Humanisation Practices in the healthcare of patients with rare diseases in Hospital Pharmacy Services. Access to the questionnaire was sent by email to the Heads of the Hospital Pharmacy Service of 18 hospitals. The study period was from October 2021 to October 2022. The analysed variables were the number of criteria that were considered met, total compliance (percentage of criteria met), by strategic line and by type or level of standard, globally and grouped by regions of Spain.

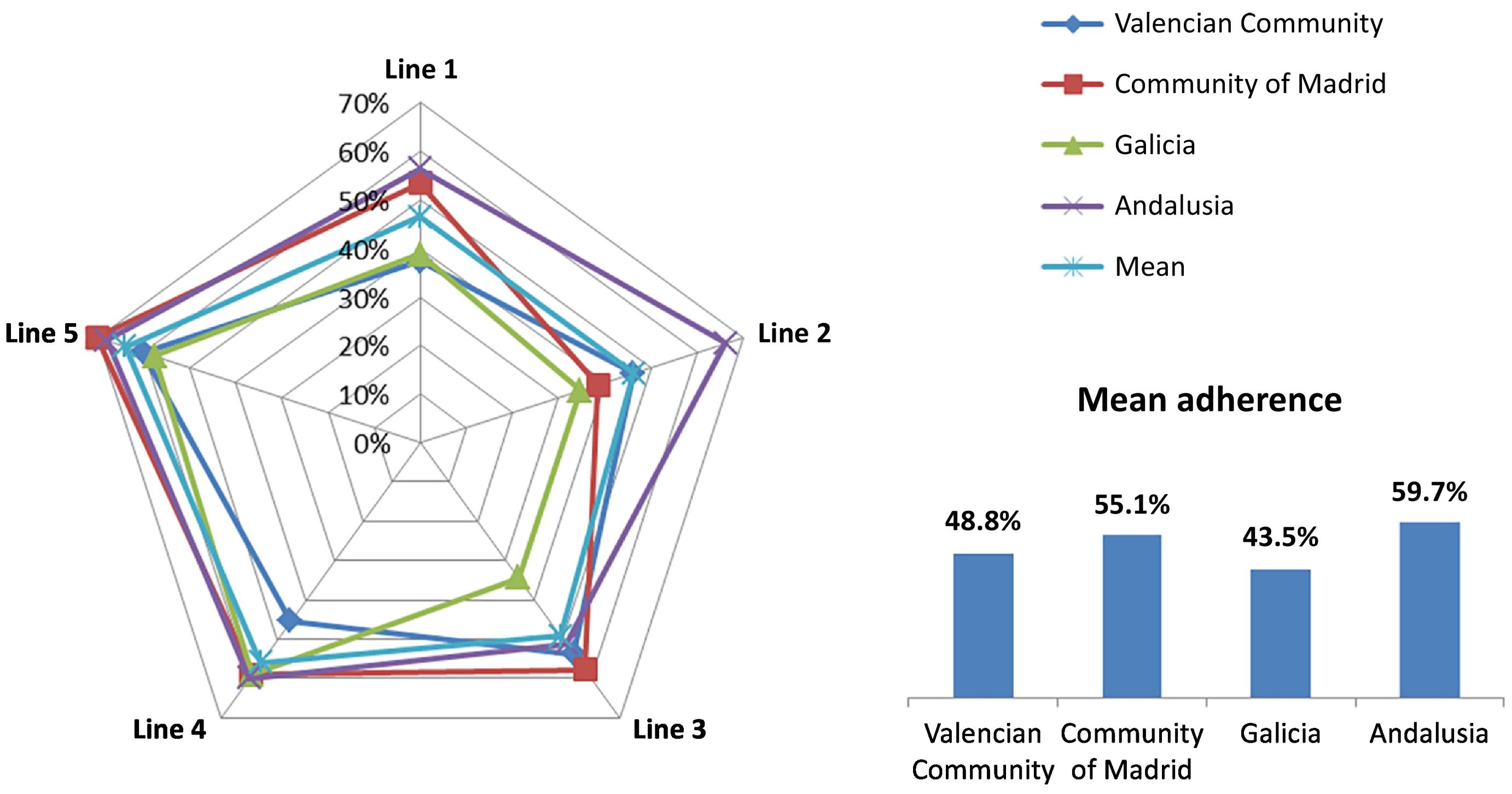

Results18 Hospital Pharmacy Services were included. The overall mean of standards met was 31.1 (95% CI: 24.8–37.6) and mean total compliance was 52.1% (95% CI: 44.4%–59.7%). The mean compliance by strategic line was: Line 1, Humanisation culture: 46.5% (95% CI: 35.3%–57.7%), Line 2, Patient empowerment: 47.4% (95% CI: 37.1%–57.8%), Line 3, Professional care: 49.7% (95% CI: 39.8%–59.1%), Line 4, Physical spaces and comfort: 55.6% (95% CI: 46.3%–64.8%), and Line 5, Organisation of healthcare: 63.8% (95% CI: 55.8%–71.9%).

ConclusionThe average compliance with the standards is between 40% and 60%, which indicates that humanisation is present in the Hospital Pharmacy Services, but there is a wide margin for improvement. The main strength in the humanisation of Hospital Pharmacy Services is a patient-centred care organisation, and the area with the greatest room for improvement is the culture of humanisation.

Analizar la presencia de Buenas Prácticas de Humanización en la atención a pacientes con enfermedades raras en los Servicios de Farmacia Hospitalaria para identificar las fortalezas y las áreas prevalentes de mejora para una atención más humanizada.

MétodosSe elaboró un cuestionario online empleando Google Form® estructurado en 2 partes: la primera recogía datos identificativos y la segunda incluía las preguntas relacionadas con el cumplimiento de los 61 estándares del manual de buenas prácticas de humanización en la atención a pacientes con enfermedades raras en los Servicios de Farmacia Hospitalaria. El acceso al cuestionario se envió por correo electrónico a los Jefes de Servicio de Farmacia Hospitalaria de 18 hospitales. El periodo de estudio fue de octubre 2021 a octubre 2022. Las variables analizadas fueron el número de criterios cumplidos, el cumplimiento total (porcentaje de criterios cumplidos) tanto por línea estratégica como por tipo o nivel de estándar (básico, BOC, avanzado o excelente), de forma global y agrupados por comunidades autónomas.

ResultadosEl estudio incluyó 18 Servicios de Farmacia Hospitalaria. La media global de estándares cumplidos fue de 31,1 (IC95%: 24,8-37,6) y el cumplimiento total medio del 52,1% (IC95%: 44,4-59,7%). La línea 1 Cultura de humanización tuvo un cumplimiento medio del 46,5% (IC95%: 35,3-57,7%), la línea 2 Empoderamiento del paciente del 47,4% (IC95%: 37,1–57,8%), la línea 3 Cuidado del profesional del 49,7% (IC95%: 39,8-59,1%), la línea 4 Espacios físicos y confort del 55,6% (IC95%: 46,3-64,8%) y la línea 5 Organización de la atención del 63,8% (IC95%: 55,8-71,9%).

ConclusiónEl cumplimiento medio de los estándares está entre el 40% y 60%, lo que indica que la humanización está presente en los Servicios de Farmacia Hospitalaria, pero existe un amplio margen de mejora. El punto fuerte en la humanización de los Servicios de Farmacia Hospitalaria se encuentra en una organización de la atención centrada en el paciente y el área con mayor recorrido de mejora es la cultura de humanización.

The humanisation of healthcare is a challenge that healthcare administrations have been tackling for decades. In our setting, as early as 1985, just 1 year after the first plan for the humanisation of healthcare was published, the Director General of INSALUD, Francesc Raventós Torras, noted that a humanised healthcare system necessitates organisations that serve people and that are designed by and made for people. This author stated that humanisation is related to management, the design of the healthcare system, the functioning of institutional structures, the mind-set of stakeholders, and professional competence.1,2 In the decades since then, humanisation has been implemented to uneven degrees in the Spanish Autonomous Regions (AR). After healthcare was decentralised in Spain, most ARs created their own humanisation plans tailored to their specific setting, and some even created general directorates of humanisation under the department of healthcare.3–6 Alongside these regional plans, a considerable number of humanisation projects have been implemented, aimed at supporting vulnerable populations.

Patients with rare diseases (RDs) have special needs regarding humanisation strategies. Actions are needed to facilitate and improve the quality of life of this group of patients and their environment—especially regarding their relationship with the healthcare system—given such factors as the lack of information about the diseases, the chronicity of the diseases, lengthy journeys to the referral centres, or the complexity of disease management. These needs motivated the creation of the Manual of Good Practices for the Humanisation of Hospital Pharmacy Services (HPSs) in the care of patients with RDs. This manual was developed by hospital pharmacists in collaboration with experts in RDs, humanisation, and patient advocacy. It is endorsed by the Rare Diseases and Orphan Drugs group of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (Orphar-SEFH). This manual outlines 5 strategic lines detailing actions, activities, or practices that address the non-clinical needs of patients with RDs, their families, and/or caregivers in their interactions with HPSs. It also incorporates initiatives to promote engagement and motivation among healthcare workers, who are key agents in humanised healthcare. The aim is to establish standards of humanisation in HPSs regarding the care of patients with RDs.7

Humanisation strategies often require considerable political and financial commitment; however, as stated in the handbook, small actions taken during daily professional activity can also lead us toward a more humanised approach to healthcare. The availability of good practice manuals contributes to a culture of continuous improvement, as does the ability to evaluate the degree of adherence to them. This study investigated the presence of good humanisation practices in the care of patients with RD within HPSs in order to identify strengths and weaknesses in the delivery of humanised care.

MethodsWe conducted an observational, descriptive, cross-sectional, multicentre study on adherence to the standards of the aforementioned manual.7 It was conducted from October 2021 to October 2022.

The manual comprises 61 standards classified into 3 levels according to the relevance of the practice and the resources needed to implement them: Basic standards, which are the foundations of humanised care; advanced standards, which are not essential, but which contribute strongly to the humanisation of care (adherence with them entails a higher level of recognition); and excellent standards, which represent an excellent level of humanised healthcare. Within the Basic standards, there is a subgroup called the Basic Mandatory Standards (BMS), which is a selection of indispensible standards. In some standards, the classification as basic, advanced, or excellent varies depending on their coverage or degree of implementation. The standards are grouped into 5 strategic lines: Line 1, Humanisation culture; Line 2, Patient empowerment; Line 3, Staff training & care; Line 4, Physical spaces and comfort; and Line 5, Organisation of care.

Based on this manual, a self-assessment questionnaire was created using Google Forms, which allows users to create questionnaire interfaces and collect, monitor, and evaluate the responses. The questionnaire was structured into 2 parts: (1) the collection of identification data (hospital name and ARs); and (2) data on adherence to humanisation standards. The questionnaire was emailed to the heads of the HPS at several hospitals in 4 of the Spanish ARs. Out of the 18 HPSs chosen, 5 were part of the Spanish Health System's list of Reference Centres, Services, and Units (CSUR) for one or several RDs. The size of the selected hospitals ranged from 160 to 1500 beds. The data obtained on each AR were collectively analysed in group meetings.

We examined variables such as the number of criteria fulfilled and total adherence (percentage of criteria fulfilled). The assessment was broken down by strategic lines and type/level of standard. To calculate the standards with higher adherence—in the case of multiple levels of adherence—we included all centres fulfilling the lower classification level. The results are expressed as means and 95% confidence intervals. Data analysis was conducted using Excel and STATA v14.2.

ResultsThe 18 participating HPS were distributed among the following ARs: 5 in the Valencian Community, 4 in the Community of Madrid, 4 in Galicia, and 5 in Andalusia.

The overall mean number of standards met was 31.1 (24.8–37.6) and mean total adherence was 52.1% (44.4–59.7). Mean adherence by strategic line was as follows: Line 1, 46.5% (35.3–57.7), Line 2, 47.4% (37.1–57.8), Line 3, 49.7% (39.8–59.1), Line 4, 55.6% (46.3–64.8), and Line 5, 63.8% (55.8–71.9). Fig. 1 presents the data by AR, Table 1 shows adherence to the standards by level, and Table 2 provides information on adherence to BMS.

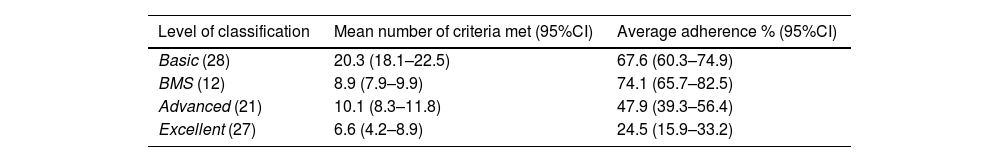

Adherence by level.

| Level of classification | Mean number of criteria met (95%CI) | Average adherence % (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic (28) | 20.3 (18.1–22.5) | 67.6 (60.3–74.9) |

| BMS (12) | 8.9 (7.9–9.9) | 74.1 (65.7–82.5) |

| Advanced (21) | 10.1 (8.3–11.8) | 47.9 (39.3–56.4) |

| Excellent (27) | 6.6 (4.2–8.9) | 24.5 (15.9–33.2) |

BMS, Basic Mandatory Standards; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

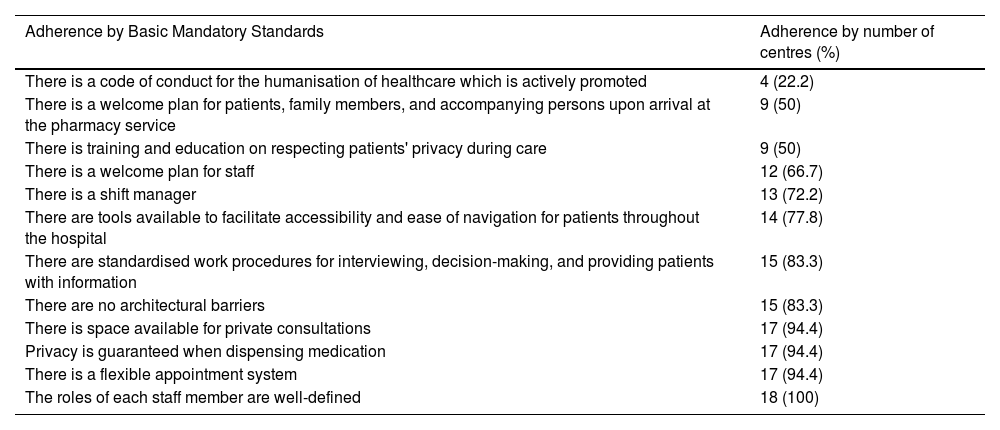

Adherence by Basic Mandatory Standards.

| Adherence by Basic Mandatory Standards | Adherence by number of centres (%) |

|---|---|

| There is a code of conduct for the humanisation of healthcare which is actively promoted | 4 (22.2) |

| There is a welcome plan for patients, family members, and accompanying persons upon arrival at the pharmacy service | 9 (50) |

| There is training and education on respecting patients' privacy during care | 9 (50) |

| There is a welcome plan for staff | 12 (66.7) |

| There is a shift manager | 13 (72.2) |

| There are tools available to facilitate accessibility and ease of navigation for patients throughout the hospital | 14 (77.8) |

| There are standardised work procedures for interviewing, decision-making, and providing patients with information | 15 (83.3) |

| There are no architectural barriers | 15 (83.3) |

| There is space available for private consultations | 17 (94.4) |

| Privacy is guaranteed when dispensing medication | 17 (94.4) |

| There is a flexible appointment system | 17 (94.4) |

| The roles of each staff member are well-defined | 18 (100) |

Table 3 shows the 10 standards by highest and lowest mean adherence. Of the 61 standards, only 3 were met by all the centres: Pharmaceutical care is provided to patients with RD; information is provided on the disease and treatment; and the roles of each professional are well-defined.

Standards with the highest and lowest adherence.

| Standards with the highest adherence | Standards with the lowest adherence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Adherencen (%) | Standard | Adherencen (%) |

| Pharmaceutical care is provided to patients with rare diseases | 18 (100) | There is a children's area | 0 (0) |

| Information is provided about the disease and treatment | 18 (100) | An alternative space is available for patients at risk of cross-infection | 0 (0) |

| The roles of each staff member are well-defined | 18 (100) | Self-care and empowerment training activities are conducted, monitored, and evaluated; the results are recorded | 1 (5.6) |

| There is a humanisation plan | 17 (94.4) | Self-care and emotional support for caregivers is encouraged | 1 (5.6) |

| Activities are conducted to raise awareness of the work of the pharmacy service | 17 (94.4) | There is a mobile/web-based app showing waiting times | 1 (5.6) |

| There is a space available for private consultations | 17 (94.4) | Co-creation and/or co-production models are used in the design of the organisational structure | 2 (11.1) |

| Privacy is guaranteed when dispensing medication | 17 (94.4) | There is a dissemination plan for actions/activities related to humanisation | 3 (16.7) |

| There is a flexible appointment system | 17 (94.4) | Healthcare workers' competencies in humanisation are evaluated | 3 (16.7) |

| Measures are in place to collect feedback from patients and carers | 16 (88.9) | There is a catalogue or repository of recommended digital content | 3 (16.7) |

| Coordinated care with the rest of the healthcare team is encouraged | 16 (88.9) | Adaptive seating is available | 3 (16.7) |

Note: Standards with multiple levels of adherence have been included when fulfilled at the lowest classification level.

The Manual of Good Practices for Humanisation of HPS in the Care of Patients with RDs covers 5 strategic lines that encompass the various dimensions of humanisation in healthcare. Overall, Line 5 (Organisation of Care) had the highest adherence rate (close to 65%). This strategic line covers best practices concerning healthcare pathways and coordination among various healthcare workers and services to facilitate patient care. The standards with the highest adherence rates included coordination with the rest of the healthcare team, the presence of a shift manager, a flexible appointment system, and delivering patient medications to healthcare centres or pharmacies. At both the national level and by AR, key factors in Line 5's high adherence rates were information and communication technologies (ICT)—which help streamline the management of appointments and other procedures for patients and their families—and the promotion of telecare, which was largely driven by the COVID-19 pandemic.8,9

Line 4 (Physical Spaces and Comfort) had the second highest adherence rate. The humanisation of physical space refers to organising hospital environments such that they are more accessible and comfortable. This strategic line seeks to minimise architectural barriers, draw attention to signs to facilitate movement within the hospital, and improve the level of physical, sensory, and environmental comfort that the spaces provide. Line 4 is one of the predominant considerations in humanisation plans in several ARs.10–13 This study found that there was high adherence to activities related to privacy, both in the provision of medicines and in the administration of treatments. However, other aspects, such as the availability of a children's area or adapted seating, are barely addressed. This line is affected by the healthcare centre's infrastructure and physical structure. Hospital architecture has evolved alongside that of society, is representative of each era's heritage, and reflects the social needs and values of the time. Currently, hospital architecture is centred on horizontal designs that favour the implementation of care processes according to the needs of patients. Spaces are designed to take into account the patient experience.14,15

Line 1 (Humanisation culture) had the lowest average adherence and the highest variability. The implementation of a humanisation culture is a longitudinal process in which humanised values permeate the organisation. The incorporation of a humanisation culture into healthcare rests on information, training, perception, and knowledge. This culture is fostered by humanisation plans and all those actions aimed at giving visibility to and promoting humanisation as a beneficial quality. The variability found in adherence to this line may have been due to the varying implementation of humanisation plans in the participating ARs. The study data show an association between greater adherence to this strategic line and higher average adherence to good practices as a whole.

Line 2 (Patient empowerment) had the second-lowest adherence rate. Empowerment attempts to give individuals greater control over decisions and actions that affect their health via information, training, and communication.16 Within this strategic line, activities related to pharmaceutical care have been expanding and adapting to changes in both society and among patients, who are increasingly aware of health issues and are motivated to engage in self-care. The lower adherence found in this line may be due to the high percentage of standards classified as excellent (53.8%). Most of these are related to the use of technology and to new educational models aimed at patients and others in their daily lives.

Finally, Line 3 (Staff training & care) had a moderate adherence rate (close to 50%). Healthcare workers are the main drivers of humanisation. However, they should also be the target of humanisation actions that foster enthusiasm and involvement. Several studies have demonstrated the existence of burnout syndrome in healthcare specialists. An improved healthcare system requires the promotion of emotional well-being and resilience among its staff, as well as improvements to the work environment.17–19 On the one hand, the most common activities involved the distribution of responsibilities and functions within HPS, such as defining professional roles and work procedures. On the other hand, the lowest adherence rates involved the creation ICT repositories and the assessment of staff competencies related to humanisation.

Adherence is inversely proportional to the level of the standard. The highest adherence level was associated with the Basic level (67.6%), whereas the lowest was associated with the Excellent level (24.5%). The classification of standards is based on the amount of material or human resources required to implement them, as well as the potential impact they could have on the humanisation of care. The data show lower adherence to standards that require greater investments for their implementation. Basic Mandatory Standards refer to activities essential to ensure humanised care7; although overall adherence to these was significant (74.1%), there was a lower degree of adherence to some of the criteria. It is noteworthy that only 21.1% of the centres have and promote a code of conduct for humanisation. Codes of conduct are not only sets of rules deemed essential to an activity, but also represent a visible commitment to humanising care. A number of codes of conduct have been published by various health departments, working groups, or clinical units. However, we were unable to find any shared codes of conduct specific to HPSs. The only BMS criterion with 100% adherence was the precise definition of each healthcare worker's role in patient care.

There is a strong relationship between humanisation and the quality of healthcare. The aim of quality healthcare is to provide treatment based on the latest scientific evidence, tailor care to each patient's needs, provide seamless continuity of care, and ensure the patient's needs are met.20 Consequently, humanisation is an integral to the concept of quality healthcare. Quality control has traditionally been a concern of institutions within the Spanish Health System, and especially in relation to HPS.21 Policies that promote quality care and continuous improvement could positively influence adherence to the humanisation standards laid out in the manual. Some ARs have developed specific strategies or plans for treating patients with RDs. These address issues such as training healthcare workers, providing patients with up-to-date information, or collaborating with patient associations.22–24 Although some ARs do not have such plans, they dedicate a section to RDs in their general health plans. Other projects have been undertaken by professional organisations to promote and facilitate humanisation, such as the SEFH Guide to Humanising Hospital Pharmacy Services, which refers to the special vulnerability of patients with RDs.25

The results of this survey should be considered in the context of its limitations, such as participant selection bias, subjectivity in the assessment of adherence to good practices, and sample size. However, this is the first study to evaluate the strengths, as well as areas for improvement, of humanisation in HPSs, especially in the field of RDs. The periodic or repeated implementation of this survey could shed light on progress in humanising care within HPSs. In addition, the content of the manual could serve as a basis for developing a certification standard for HPSs, given that the external evaluation and recognition of certification could promote the implementation of humanisation strategies.

Overall, adherence to standards ranged from 40% to 60%, suggesting that although humanisation practices are present within HPSs, there is a wide margin for improvement. The most progress in HPSs has been made in the organisation of patient-centred care, whereas the greatest potential for improvement lies in the area of humanisation culture. The hospitals included in this study have similar profiles regarding their adherence to various strategic lines, albeit with some exceptions. The main drivers of adherence seem to be policies and humanisation strategies implemented at the regional level. Other factors that may influence adherence to standards include the existence of programs for continuous improvement in service quality, and the design of the healthcare centres themselves. Some standards have low implementation across all HPSs. These are prime candidates for collaborative efforts to develop programs that strive for the highest level of humane care. Examples include establishing a common HPS code of conduct or a standardised model for patient reception.

Contribution to the scientific literatureWe present an overview of the situation regarding hospital pharmacy services in terms of humanising care and identify areas for improvement and potential lines of research.

FundingNone declared.

Author contributionsMaría José Company Albir contributed to the concept, design, definition of intellectual content, literature search, data collection and analysis, statistical analysis, preparation, editing, and revision of the manuscript and accepts responsibility for the article.

José Luis Poveda Andrés contributed to the design, definition of intellectual content, data collection, preparation, editing, and revision of the manuscript and accepts responsibility for the article.

María Dolores Edo Solsona contributed to the concept, preparation, editing, and revision of the manuscript and accepts responsibility for the article.

We would like to thank all the HPSs that completed the self-evaluation questionnaires for their contribution to the study.