To analyse a patient journey based on the experience reported by breast and lung cancer patients at Spanish hospital.

MethodA mixed design was used, with interviews with 16 health professionals and 25 patients (qualitative method) and a Net Promoter Score questionnaire to 127 patients (quantitative method). Inclusion criteria: oncology patients > 18 years treated in hospital between February- May 2019. Exclusion criteria: paediatric patients, in palliative care or who were hospitalised at the time of the study.

ResultsSix phases were identified from the data obtained in the qualitative method: my life before diagnosis; discovery; initiation; treatment; follow-up; and my current life. In the my life before diagnosis phase, a functional level of experience was established, as patients’ lives met their expectations. In the discovery phase, patients’ expectations were observed to be met, although several satellite experiences were found. In the initiation phase, the experience tended to be negative due to long waiting times and emotional and physical stress. The treatment phase was defined as a basic-poor experience, due to waiting times and lack of institutional support. The experience in the follow-up phase was positive in terms of tests and visits, but critical points were observed in waiting times. In the current phase, the effort made by health professionals to ensure the best possible treatment and care was mentioned. In terms of quantitative analysis, a positive score (46%) was obtained for the Net Promoter Score indicator, as 60% of patients were promoters, i.e. they were satisfied with the service offered by the hospital.

ConclusionsThis study provides insight into the experience of cancer patients in the six main stages of the disease. The most positive phases were “my life before diagnosis’ and “follow-up’ while the phases with a negative trend were “initiation’ and “treatment’ due to the waiting times and the emotional burden on the patient.

Analizar la experiencia aportada por los pacientes con cáncer de mama y pulmón utilizando la metodología del recorrido del paciente en un hospital español.

MétodoSe empleó un diseño mixto, con entrevistas a 16 profesionales sanitarios y 25 pacientes (método cualitativo), y un cuestionario basado en el indicador Net Promoter Score a 127 pacientes (método cuantitativo). Criterios de inclusión: pacientes oncológicos > 18 años tratados en el hospital entre febrero y mayo de 2019. Criterios de exclusión: pacientes pediátricos, en cuidados paliativos o que estaban hospitalizados en el momento del estudio.

ResultadosSe identificaron seis fases a partir de los datos obtenidos en el método cualitativo: mi vida antes del diagnóstico, descubrir, comenzar, tratamiento, seguimiento y mi vida hoy. En la fase mi vida antes del diagnóstico se estableció un nivel de experiencia funcional, ya que la vida cumplía las expectativas de los pacientes. En la fase de descubrir se observó que las expectativas de los pacientes se cumplían, aunque se encontraron varias experiencias satélite. En la fase comenzar, la experiencia tendió a ser negativa debido a los largos tiempos de espera y al estrés emocional y físico. La fase de tratamiento se consideró como una experiencia de nivel básico-deficiente, debido a los tiempos de espera y a la falta de apoyo institucional. La experiencia en la fase de seguimiento fue positiva respecto a las pruebas y las visitas, pero se observaron puntos críticos en los tiempos de espera. En la fase mi vida hoy se mencionó el esfuerzo realizado por los profesionales sanitarios para garantizar el mejor tratamiento y atención posibles. En cuanto al análisis cuantitativo, se obtuvo una puntuación positiva (46%) para el indicador Net Promoter Score, ya que el 60% de los pacientes pertenecían a la categoría de promotores, es decir, estaban satisfechos con el servicio ofrecido por el hospital.

ConclusionesEste estudio permite conocer la experiencia de los pacientes oncológicos en las seis etapas principales de la enfermedad. Las fases más positivas fueron “mi vida antes del diagnóstico’ y “seguimiento”, mientras que las fases con tendencia negativa fueron “inicio’ y “tratamiento’ debido a los tiempos de espera y la carga emocional que suponen para el paciente.

Globally, cancer is a major public health problem and the second leading cause of death, with an estimated 9.6 million deaths during 20201, with lung cancer, colon cancer and breast cancer as the three most common causes of death. According to the World Health Organization, 18.1 million people worldwide were affected by cancer in 2018 and this figure could reach 29.5 million in 20401–3.

Currently, cancer is associated with a significant clinical and economic burden on healthcare systems and on patients and their families4–6. Furthermore, because of an ageing and growing population, along with lifestyle changes, the global burden of this disease continues to increase5. Thus, cancer control is now a priority in public health.

Despite advances in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cancer, cancer patients show multiple and often severe symptoms, regardless of the stage of the disease7,8. Additionally, most healthcare reforms and policies emphasize the need to support patients in taking a more active role in managing their disease, thus implementing patient-centred care. This approach is determined by the quality of interactions between patients and healthcare professionals, thus improving disease outcomes and patients’ quality of life9. Therefore, improving people's experience of care through patient-reported measures is crucial. Currently, two main patient report measures exist as follows: patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and patient-reported experience measures (PREMs). PROMs measure a person's perceptions of healthcare, while PREMs capture a person's perceptions of their experience while receiving care10. The implementation of PREMs can help to highlight the strengths and weaknesses reported by the patient in relation to clinical effectiveness and patient safety11, and PROMs are associated with improved symptom control, increased care measures and improved patient satisfaction12,13. Therefore, it would be desirable to consider these measures as one of the fundamental pillars of quality in healthcare.

Several studies have shown that PROMs are widely and routinely used in various disciplines14–17 including oncology18,19. However, the application of PREMs is limited, particularly in oncology care. In an extensive review, seven measuring tools were used for PROMs, but only one was used for PREMs20. Therefore, present study aimed to explore the PREMs in breast and lung cancer patients using the patient journey methodology at Spanish hospital.

MethodsA mixed design was used, including semi-structured interviews with healthcare professionals and patients and contextual observation (qualitative method) and a questionnaire (online or personal interview) for patients (quantitative method) to explore a patient journey based on their experience and to construct a map for the whole process.

The study protocol was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee. All the participants offered their written informed consent before the interview.

Study sampleAdult patients (> 18 years) with lung or breast cancer treated at hospital in Toledo from February to May 2019 were included. Eligible criteria included oncology patients who had undergone any of the disease stages and could interact with hospital healthcare professionals treating their disease. Of the 150 eligible patients, 23 were excluded due to refusal to participate in the study or because of lack of follow-up, resulting in a final sample of 127 patients (82 with breast cancer and 45 with lung cancer).

The exclusion criteria included the following: paediatric patient, patients in palliative care and patients who were hospitalized at the time of the study.

Regarding healthcare professionals, we included those professionals who had direct contact with patients with lung or breast cancer throughout all phases of their disease, with the aim of understanding the professional context of key moments, thus helping to identify aspects with a direct impact on the patient's experience.

Data collectionQualitative research methodFace-to-face interviews were conducted with 16 healthcare professionals and 25 patients. The interviews lasted approximately 45–60 minutes and were divided into two sections: one section comprising general questions and another comprising questions related to the patient journey (Tables 1 and 2).

Questions included in interviews with healthcare professionals

| HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONAL'S PROFILE |

|

| PATIENT JOURNEY |

| Discovery stage |

|

| Initiation stage |

|

| Treatment stage |

|

| Follow-up stage |

|

| CLOSE THE INTERVIEWS |

|

Questions included in interviews with patients

| PATIENT'S PROFILE |

|

| PATIENT JOURNEY |

| Discovery stage |

|

| Initiation stage |

|

| Treatment stage |

|

| Follow-up stage |

|

| CLOSE THE INTERVIEWS |

|

First, interviews were conducted with the main healthcare professionals who usually interact with cancer patients at the hospital to identify the key points and learn about the vision and perception of the experience they believe patients live related to these interactions with healthcare professionals. Sixteen interviews were performed with the following healthcare professionals: oncologists (n = 6), surgeon (n = 1), radiologists (n = 2), nurses and oncology assistants (n = 4), nurses and pharmacy assistants (n = 2) and hospital pharmacists (n = 1). Subsequently, 25 cancer patients (10 early breast cancer patients, 5 metastatic breast cancer patients and 10 lung cancer patients) were interviewed to determine their experience throughout the cycle of their disease, their relationship with the hospital, elements of satisfaction and dissatisfaction along their journey, and their expectations and needs associated with each stage. In these interviews, the points previously identified by healthcare professionals were contrasted so that patients could add or remove interactions of the journey previously drawn by the team of healthcare professionals.

Once the interviews in both groups were completed, a contextual observation was carried out. This process comprised accompanying the consultation assistants and observing the most relevant points in the hospital related to the development of the patient journey (e.g., waiting room, chemotherapy room, etc.).

Quantitative research methodTo complement the data obtained in the previous phase, a structured questionnaire was distributed to 127 patients (82 patients with breast cancer and 45 with lung cancer). This questionnaire included 26 questions (7 questions on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, 3 questions related to logistical aspects, accommodation, or infrastructure and 16 questions on the different stages of the patient journey).

The questionnaire was developed using the customer experience and patient experience methodology, based on the net promoter score (NPS) indicator21–23. The NPS is based on a single question: How likely is it that you would recommend our service to a friend or colleague? Participants respond ranging from 0 (“not at all likely”) to 10 (“extremely likely”). The assumption is that individuals scoring 9 or 10 will provide positive wordof-mouth advertising; they are called “promoters”. Individuals scoring 7 or 8 are considered indifferent (“passives”). Finally, individuals scoring 0–6 are likely to be dissatisfied customers and are labelled “detractors”. The NPS is then calculated as the percentage of “promoters” minus that of “detractors”19.

Data analysisTo ensure rigorous analysis, all the interviews were conducted by an external consultant from a consultancy firm specialized in Patient Experience (IZO), and subsequently reviewed and validated by the project coordinators. The patients’ emotions, reported or observed, were classified according to Plutchik's Wheel of Emotions24.

Quantitative data were created from the qualitative questionnaire. According to the NPS methodology20, counts were calculated for questions using a scale of 0–10 points, grouped into promoters or satisfied (score 9–10), neutrals (score 7–8) and detractors or dissatisfied (score 0–6), as has been previously stated.

After that, a thorough analysis was performed by the external consultant to correlate the qualitative and quantitative data and analyse the categories and meaning that resulted. This approach was applied to develop a process map that ensured a comprehensive representation of the patient journey.

ResultsParticipant demographicsData were collected for 127 patients with lung and breast cancer. Most of the participants had breast cancer (65.0%), and the remaining 35.0% had lung cancer. The age range of the study participants was between 26–79 years. 74% of the participants were female. 32 participants were on treatment for less than one year (25.2%), 51 participants for 1–3 years (40.1%), 36 participants for 3–10 years (28.3%) and 8 participants for more than 10 years (6.3%) (Table 3).

Patient demographics

| Patients (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nationality | ||

| Spanish | 124 (97.6%) | |

| Other | 3 (2.3%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 33 (26.0%) | |

| Female | 94 (74.0%) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 26-35 | 2 (1.5%) | |

| 36-45 | 14 (11.0%) | |

| 46-64 | 81 (63.7%) | |

| > 65 | 30 (23.6%) | |

| Treatment time | ||

| < 1 year | 32 (25.2%) | |

| 1-3 years | 51 (40.1%) | |

| 3-10 years | 36 (28.3%) | |

| > 10 years | 8 (6.3%) | |

| Cancer diagnosis | ||

| Breast | 82 (65.0%) | |

| Lung | 45 (35.0%) | |

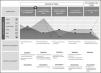

The following six phases were identified during the disease course: 1) My life before diagnosis; 2) discovery; 3) initiation; 4) treatment; 5) follow-up; 6) my current life.

My life before diagnosis stageAt this stage, only the interaction of “my day-to-day” was considered. Patients at this stage showed a functional level of experience, with most commenting that their life met their expectations in relation to their lifestyle and personal plans (Figure 1).

Discovery stageSix interactions were described: 1) a warning sign appears around my health; 2) I undergo diagnostic tests; 3) I wait for the results of the diagnosis; 4) I confirm the diagnosis of cancer; 5) I discuss it with my social environment (family, friends, work); 6) I am informed about my disease and treatment (Figure 1).

Regarding the patient's experience at this stage, the patient's expectations of healthcare professionals and hospital procedures were met. However, several satellite experiences were found in the same interaction, reflecting those certain processes are not standardized or that, the patient experience can be very different depending on who performs them.

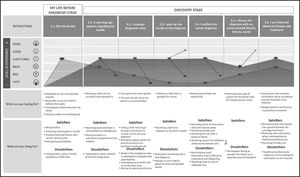

Initiation stageIn the initiation stage, the following interactions were collected: 1) I agree to start treatment; 2) I attend my first chemotherapy session; 3) I undergo surgery; 4) I start oral treatment (Figure 2).

In patient interviews, these interactions are critical because they represent a high degree of emotional and physical stress that must be experienced repeatedly over months or years. Additionally, at this stage, the patients’ experience may be negative, because expectations of interaction with the hospital are not met. The reason is likely the long waiting times to be attended to or receive services in the hospital and negative perceptions of waiting room facilities for tests, consultations, and treatment administration processes.

Treatment stageDuring the treatment stage, six interactions were defined as follows: 1) I received more cycles of chemotherapy; 2) I received other treatments (radiotherapy, immunotherapy, hormonotherapy); 3) I faced the effects of the treatment; 4) I received medicines from the pharmacy (oral treatment); 5) I changed my habits; 6) I found and received support (Figure 2).

At this stage, the patients reported that the waiting times again affected their experience. Additionally, they mentioned incomplete institutional support to better understand and manage the adverse effects of treatments and changes in habits due to the disease. Thus, the patients valued this stage with a level of experience between basic and poor because, the minimum expectation was met for some patients but not for others, generating a negative memory.

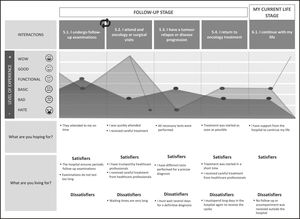

Follow-up stageFour interactions were defined at this stage: 1) I underwent follow-up examinations; 2) I attended an oncology or a surgical visit; 3) I had tumour relapse or disease progression; 4) I returned to oncology treatment (Figure 3).

In the interviews with the patients, the importance of this stage was indicated because it allows them to understand the evolution of their disease. The experience reported by patients was positive concerning the frequency of testing, type of tests performed to make an accurate diagnosis and visit quality. However, critical points were observed regarding the waiting times that patients should assume both to attend follow-up consultations and receive oncological treatment when they relapse.

My current life stageAt this stage, only one interaction was determined: 1) continue with my life (Figure 3).

Patients reported that one of the main goals of this stage is to have a good quality of life and resume their personal routines and projects. The experience reported by patients regarding the hospital was poor because, they believe that they did not receive support to continue with their daily lives. However, they mentioned the substantial effort made by the healthcare professionals team to ensure that treatment and care were as good as possible.

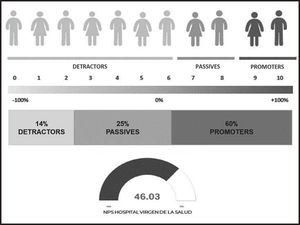

Quantitative method.Net promoter score indicatorRegarding quantitative analysis, a positive score (46.03%) was obtained for the NPS indicator of the hospital. The reason is that, 60.0% of the patients were promoters, indicating they were satisfied with the hospital service, their expectations were met in several patient travel interactions, and they had positive memories of their hospital experience. The most relevant reason patients reported was the attention received by healthcare professionals at all stages of the patient's journey (86.5%), followed by the ease of access to treatment (39.7%) (Figure 4).

In relation to interaction with healthcare professionals, more than half of the patients (52.8%) indicated that the reference person in the hospital is their oncologist, both because of the clinical approach and because of the emotional bond created over months or years of follow-up.

Finally, regarding the stages of the patient's journey, the quantitative analysis focused on exploring the four stages at which patients interact directly with hospitals, healthcare professionals and services (discovery, initiation, treatment, and follow-up). At the discovery stage, one of the most important moments for patients was the diagnosis. Most of the patients (70.0%) believed that this was a quick process and that their expectations in terms of waiting time were met. At the initiation stage, patients mentioned that preparation for the disease and receiving support at this stage are two key aspects; however, only 48.0% of patients reported having received help from hospital professionals. At the treatment stage, 50.0% of patients expressed that they had not used the pharmacy service or that they had no information about it. At the follow-up stage, patients reported receiving less support from the hospital to continue with their daily lives.

DiscussionAs previously stated, PROMs as an objective (and therefore measurable) experience of patients are widely disseminated. However, PREMs, as a subjective, and largely emotional, experience, are much more challenging to obtain, particularly in cancer patients26. The number of tools to measure PREMs is much scarcer and less reliable than for measuring PROMs22. This patient journey was designed to examine the patient experience of breast and lung cancer patients using the healthcare system at a third-level general hospital.

To our best knowledge, this study is the first to describe the experiences of breast and lung cancer patients in Spain using a mixed design of qualitative and quantitative research methods. In a review of the literature, several studies have been located that have developed patient journey maps for this disease using qualitative analysis26,27. A study conducted in the United States26 shows that the main factors contributing to the fragmentation of cancer care in the healthcare system are the communication barriers that exist between healthcare professionals and the lack of continuity of patient care especially in the treatment phase. Another study27 identified significant disparities in care between European countries, with differences in treatment for a skin cancer patient, and recommends further research and efforts to address health inequalities, thereby improving the quality of care and reducing skin cancer morbidity. Therefore, these publications using qualitative methods show the lack of communication with the patient, and the lack of shared care for cancer management among different healthcare professionals, leading to divided care for this disease in the healthcare system.

Cancer is a disease with a considerable emotional impact on patients, leading to possible psychiatric, neuropsychiatric, and psychosocial disorders that impact their quality of life28. In our study, we observed that although most patients recognized that one of the main challenges of living with cancer is emotional support, very few requested psychological support. The reason is likely because they were not sufficiently informed about how to reach those psychotherapeutic services in the hospital or because they did not feel that they might be useful. Therefore, it would be interesting to improve psychotherapy services in the hospital by making a comprehensive approach that includes both the therapeutic approach and the psychosocial and occupational intervention. In this way, patients would feel to be supported in all areas, thus improving their experience during disease management and follow-up in the hospital setting.

This study identified some unmet needs and areas for improvement in the management of cancer patients at Toledo hospital. As other authors have already established29, our findings confirm that one of the most conflicting aspects expressed by patients was the long waiting time to be attended. In the interviews, patients evaluated this aspect beyond the discomfort generated by the diagnostic tests and treatment procedures. By contrast, the care of patients by the healthcare professionals is one of the main reasons for which those patients valued the whole hospital experience very positively despite this aspect. Finally, from the interviews conducted with healthcare professionals, in their daily lives, patients faced considerable emotional, and work demands, that negatively affect their wellbeing and the balance of their personal lives, often evidencing stress and sadness in these situations.

This pilot study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting these findings. The main limitation is the size of the sample analysed; information was only collected from 127 patients from the hospital in Toledo. Furthermore, only patients with two specific types of cancer (breast and lung) were considered. However, these two types of cancer are the most frequent in humans and are among those that produce the highest mortality (lung cancer, ranked first, with 1.8 million deaths in 2020; breast cancer, ranked 5th, with 685,000 deaths in 2020)1. Therefore, although only two types of cancer were investigated in this study, they represent a significant proportion of the oncological population in the hospital setting.

Another limitation that must be considered is that this study shows preliminary and exploratory data collection on the route taken by cancer patients through the healthcare system, making it possible to identify areas for improvement and specific action plans that can be used to develop future studies in more hospitals and including patients with other types of tumours.

This study provides insight into the experience of cancer patients during all stages of the disease in the hospital setting. Additionally, our findings shed light on how cancer may impact patients’ lives and may have important implications for clinical practice. Despite the rigorous study design, these results should be interpreted accounting for the qualitative and quantitative nature of the data collected and size of the sample used because, as all the patients included in the study were from Toledo Hospital, so our results may not reflect the complete experience of cancer patients in other settings. Therefore, further research is needed to develop validated tools to evaluate patient experience in healthcare systems.

In conclusion, this patient journey identified six main phases throughout all stages of the disease. The most positive phases were my life before diagnosis phase and the follow-up phase, while the phases with a negative tendency were the initiation phase and the treatment phase, due to the waiting times and the emotional and physical burden on patients. According to the NPS, the care provided by the hospital is positive for 46.03% of the patients.

FundingThis study was funded by Pfizer Spain.

Conflict of interestMiguel Ángel Casado and María Mareque are currently employed at PORIB, a consultant company specialized in economic evaluation of health interventions, which received financial support from Pfizer for the development of the manuscript for this study. Javier Soto is employed of Pfizer Spain.

Early Access date (07/16/2022).