To assess the usefulness of a tool based on ICD-10 diagnostic codes to identify patients who consult an emergency department for adverse drug events (ADE).

MethodsProspective observational study, in which patients discharged from an emergency department during May to August 2022 with a diagnosis coded with one of the 27 ICD-10 diagnoses considered as triggers were included. ADE confirmation was carried out by analyzing drugs prescribed prior to admission, and through a discussion among experts and a phone interview with patients after hospital discharge.

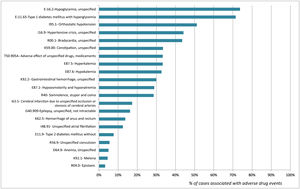

Results1143 patients with trigger diagnoses were evaluated, of which 310 (27.1%) corresponded to patients whose emergency visit was attributed to an ADE. A 58.4% of ADE consultations were found with three diagnostic codes: K59.0-Constipation (n = 87; 28.1%), I16.9-Hypertensive Crisis (n = 72; 23.2%) and I95.1-Orthostatic hypotension (n = 22; 7.1%). The diagnoses with the highest degree of association with consultations attributed to ADE were E16.2-Hypoglycemia, unspecified (73.7%) and E11.65-Type 2 diabetes mellitus with hyperglycemia (71.4%), while diagnoses D62-Acute posthemorrhagic anemia and I74.3-Embolism and thrombosis of arteries of the lower limbs were not attributed to any case of ADE.

ConclusionsThe ICD-10 codes associated with trigger diagnoses are a useful tool to identify patients who consult the emergency services with ADE and could be used to apply secondary prevention programs to avoid new consultations to the health care system.

Evaluar la utilidad de una herramienta basada en los códigos diagnósticos CIE-10 para identificar pacientes que consultan a un servicio de urgencias por acontecimientos adversos por medicamentos (AAM).

MétodosEstudio observacional prospectivo, en el cual se incluyeron los pacientes que acudieron a un servicio de urgencias durante el periodo mayo-agosto 2022 con un diagnóstico codificado con alguno de los 27 diagnósticos CIE-10 establecidos como alertantes para el estudio. La confirmación de la presencia de AAM a partir de dichos diagnósticos se realizó analizando los fármacos prescritos previamente al ingreso, a través de un debate entre expertos y mediante una entrevista telefónica con los pacientes.

ResultadosSe evaluaron 1143 pacientes con diagnósticos alertantes, de los cuales 310 (27,1%) correspondieron a pacientes cuya consulta se atribuyó a un AAM. El 58,4% de los AAM se detectaron mediante 3 códigos diagnósticos: K59.0-Estreñimiento (n = 87; 28,1%), I16.9-Crisis hipertensiva (n = 72; 23,2%) e I95.1-Hipotensión ortostática (n = 22; 7,1%). Los códigos diagnósticos con mayor grado de asociación con AAM fueron: E16.2-Hypoglycemia, unspecified (73.7%) y E11.65-Diabetes mellitus tipo 2 con hiperglucemia (71,4%), mientras que los diagnósticos D62-Anemia poshemorrágica aguda e I74.3-Embolia y trombosis de arterias de los miembros inferiores no identificaron ningún AAM.

ConclusionesLos códigos CIE-10 asociados a diagnósticos alertantes son una herramienta de utilidad para identificar pacientes que consultan los servicios de urgencias por AAM y podrían ser utilizados para abordar intervenciones de prevención secundaria dirigidas a evitar nuevas consultas al sistema sanitario.

Adverse drug events (ADE), defined as any mild or severe injury resulting from the therapeutic use (including the lack of use) of a drug1, are a serious public health problem, frequently associated with preventable iatrogenia. It is estimated that 5-10% of hospital admissions, and 10-30% of admissions to emergency departments (EDs) are related to ADEs, which are most considered preventable2–4.

Several studies have been conducted in the last decade to assess the role of multidisciplinary programs in secondary prevention of ADEs. The evidence obtained demonstrates that these programs may reduce the risk for repeated consultations and hospital readmissions5–8. Yet, despite the high prevalence of this health problem, routine use of tools for the identification of patients admitted to the ED with an ADE has not yet been established. However, this population of patients is at a high risk of short-term readmission to the ED4. Thus, these patients are candidate to pharmaceutical care interventions for the optimization of their drug therapies.

For decades, the International Classification of Diseases and Health-related problems (ICD) has been the foundation for comparing global and national health trends9. The CIE-10-ES standard has been used in Spain since 2016. These useful codes help categorize admission reasons and can be used to identify patients with a diagnosis of ADE. The ICD standard has been used in various studies to identify patients hospitalized with an ADE10,11. However, the reported experience with its implementation in EDs is limited.

The purpose of this study was to assess the efficacy of an ICD-10-based tool in the identification of patients admitted to the ED with an ADE.

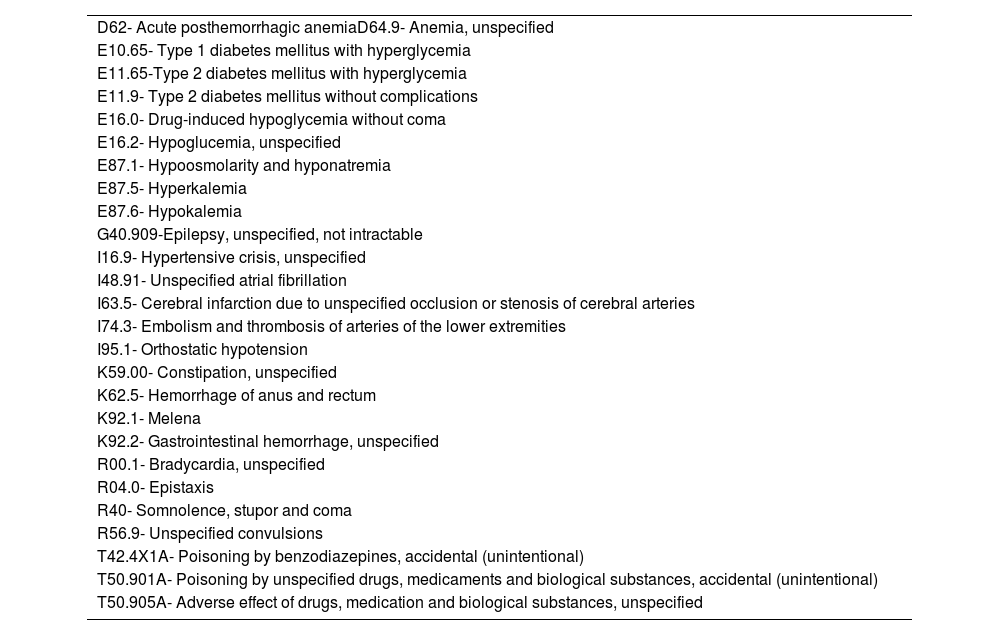

Materials and methodsA descriptive observational study was designed. The study prospectively included patients admitted to the ED between May 2022 and August 2022 with one of the 27 alert ICD-10 diagnostic codes for ADEs evaluated in the study (table 1). This list of trigger ICD-10 diagnostic codes was designed by a task force of pharmacists and emergency care consultants involved in a secondary prevention program of new consultation for ADE implemented in the center12. The study was performed in a university 644-bed hospital with near 140,000 annual ED admissions.

ICD-10 diagnostic codes evaluated.

| D62- Acute posthemorrhagic anemiaD64.9- Anemia, unspecified |

| E10.65- Type 1 diabetes mellitus with hyperglycemia |

| E11.65-Type 2 diabetes mellitus with hyperglycemia |

| E11.9- Type 2 diabetes mellitus without complications |

| E16.0- Drug-induced hypoglycemia without coma |

| E16.2- Hypoglucemia, unspecified |

| E87.1- Hypoosmolarity and hyponatremia |

| E87.5- Hyperkalemia |

| E87.6- Hypokalemia |

| G40.909-Epilepsy, unspecified, not intractable |

| I16.9- Hypertensive crisis, unspecified |

| I48.91- Unspecified atrial fibrillation |

| I63.5- Cerebral infarction due to unspecified occlusion or stenosis of cerebral arteries |

| I74.3- Embolism and thrombosis of arteries of the lower extremities |

| I95.1- Orthostatic hypotension |

| K59.00- Constipation, unspecified |

| K62.5- Hemorrhage of anus and rectum |

| K92.1- Melena |

| K92.2- Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, unspecified |

| R00.1- Bradycardia, unspecified |

| R04.0- Epistaxis |

| R40- Somnolence, stupor and coma |

| R56.9- Unspecified convulsions |

| T42.4X1A- Poisoning by benzodiazepines, accidental (unintentional) |

| T50.901A- Poisoning by unspecified drugs, medicaments and biological substances, accidental (unintentional) |

| T50.905A- Adverse effect of drugs, medication and biological substances, unspecified |

Patients with suspicion of an ADE were identified from the hospital discharge database (SAP BusinessObjects). During the study period, a daily list of patients discharged with trigger CDI codes was obtained electronically. A three-step process was used for confirmation of ADE diagnosis. Firstly, a search was performed of electronic prescriptions previous to admission that could have contributed to the reason of consultation. When a previous prescription was identified, the case was discussed by a multidisciplinary team with more than three years of experience in the identification of ADEs in the ED, on the basis of: (i) the algorithm of causality of suspected ADEs developed by Naranjo et al.13; (ii) the need for non-prescription treatments based on clinical practice guidelines; (iii) patient adherence to treatment, as assessed using the Morisky-Green questionnaire14 completed by the patient telephonically after ED/hospital discharge, in case the patient had been hospitalized. The percentage of association of each ICD code with a final diagnosis of ADE was estimated as the relationship between the number of ADEs identified for a specific ICD-10 diagnosis and the total number of cases identified with that diagnostic code. Diagnoses with less than five cases of ADE recorded during the study period were excluded.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Stata v.13.0. software package.

ResultsDuring the study period, a total of 1,151 patients admitted with a trigger ICD-10 code were included. Eight of them were excluded, as less than five cases were identified with the same diagnosis. According to the identification process described above, of the 1,143 patients included, 310 (27.1%) were identified to have an ADE. Mean age was 75.0 (SD=15.1) years, and the median of prescription medicines used on admission was 8 (range = 1–22).

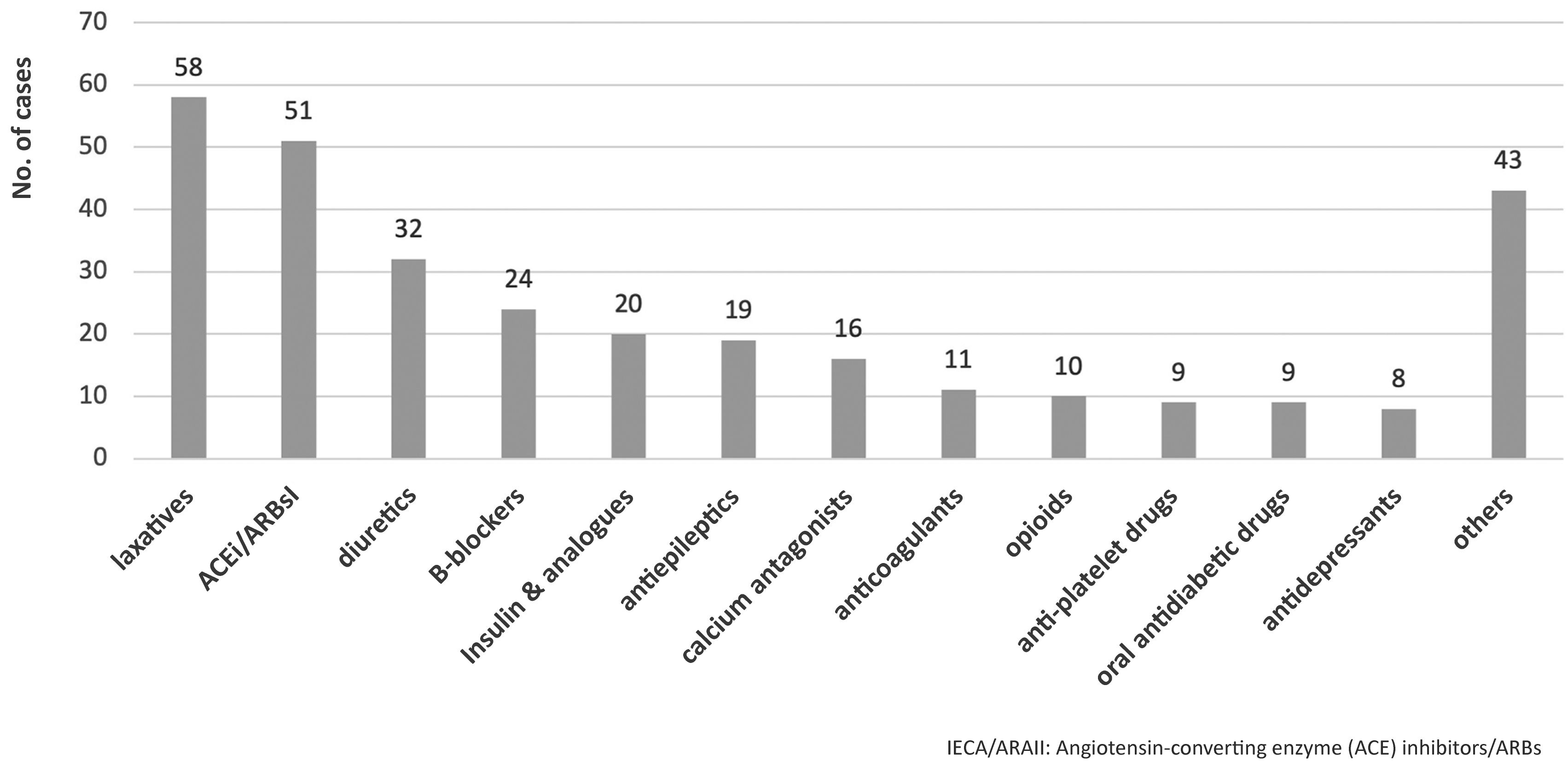

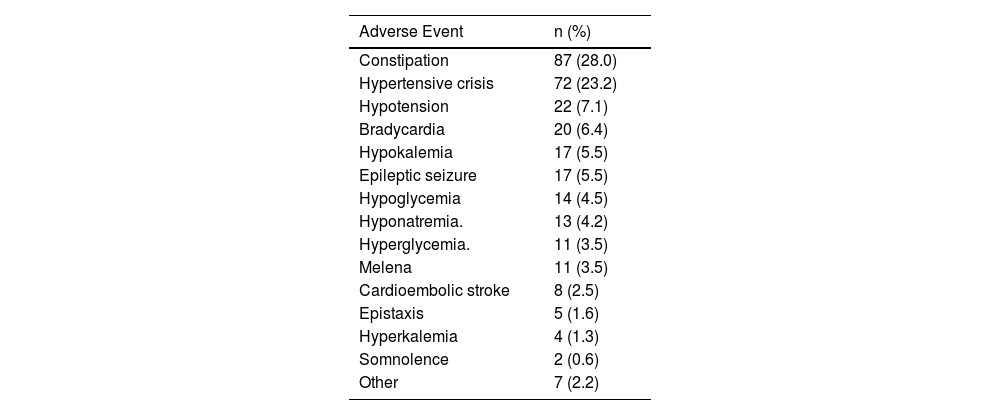

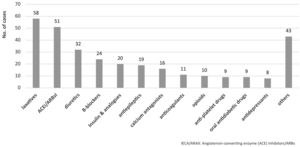

The main therapeutic groups involved in ADEs are detailed in Fig. 1. Table 2 shows the most frequent ADEs. Of the 310 cases of ADE identified, 109 (35.1%) were adverse reactions, with diuretics (n = 23) and beta-blockers (n = 13) being the most frequently involved drugs. In total, 92 (29.7%) cases resulted from failure to prescribe a treatment, mainly laxatives (n = 51) and ACE inhibitors (n = 30). In addition, 38 ADEs (12.2%) were due to lack of adherence, especially to antiepileptic drugs (n = 17) and insulin (n = 6); 36 ADEs (11.6%) were due to overdosing, especially of insulin (n = 10) and beta-blockers (n = 8); and 35 ADEs (11.9%) resulted from underdosing of ACE inhibitors (n = 10), calcium antagonists (n = 10) and others. A total of 80 (25.8%) patients were hospitalized.1

Main adverse drug events identified.

| Adverse Event | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Constipation | 87 (28.0) |

| Hypertensive crisis | 72 (23.2) |

| Hypotension | 22 (7.1) |

| Bradycardia | 20 (6.4) |

| Hypokalemia | 17 (5.5) |

| Epileptic seizure | 17 (5.5) |

| Hypoglycemia | 14 (4.5) |

| Hyponatremia. | 13 (4.2) |

| Hyperglycemia. | 11 (3.5) |

| Melena | 11 (3.5) |

| Cardioembolic stroke | 8 (2.5) |

| Epistaxis | 5 (1.6) |

| Hyperkalemia | 4 (1.3) |

| Somnolence | 2 (0.6) |

| Other | 7 (2.2) |

As many as 58.4% of ADEs were detected by three diagnostic codes: K59.0-Constipation (n = 87; 28.1%), I16.9-Hypertensive crisis (n = 72; 23.2%) and I95.1-Orthostatic hypotension (n = 22; 7.1%).

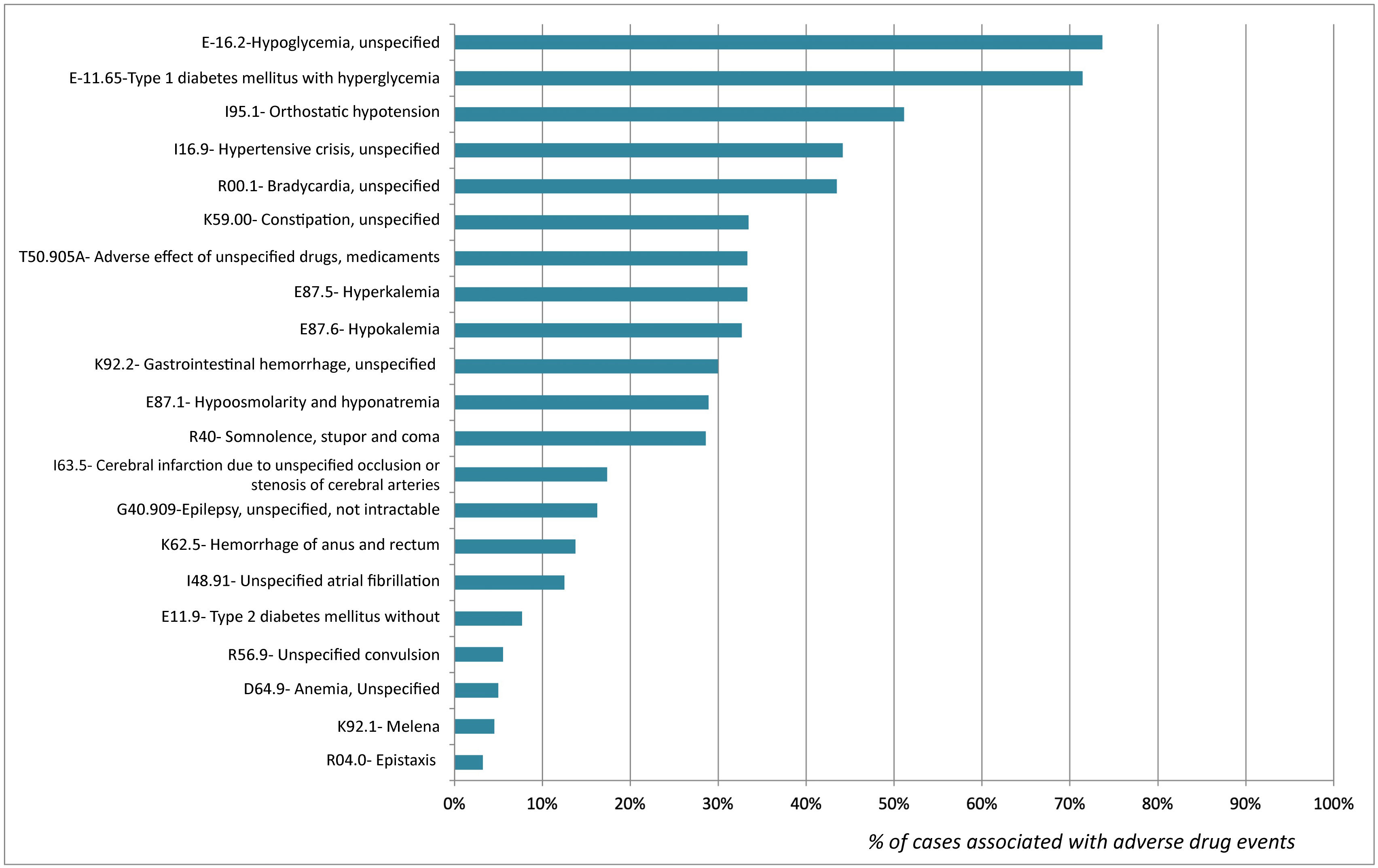

The percentages of association of the diagnostic codes included and the detection of ADE are shown in Fig. 2. Diagnoses with a higher level of association with ADE cases were E16.2-Hypoglycemia, unspecified (73.7%) and E11.65- Type 1 diabetes mellitus with hyperglycemia (71.4%). In contrast, D62- Acute posthemorrhagic anemia and I74.3- Embolism and thrombosis of arteries of the lower extremities were not associated with any ADE case.2

DiscussionThe results of this study reveal that diagnostic codes ICD-10 K59.0-Constipation, I16.9-Hypertensive crisis and I95.1-Orthostatic hypotension made it possible to identify a large number of patients admitted to the ED with an ADE. Conversely, diagnostic codes E11.65-Type 1 diabetes mellitus with hyperglycemia and E16.2-Hypoglycemia unspecified had a >70% power to detect patients with ADEs.

Screening tools including trigger diagnostic codes for the detection of ADEs have been successfully implemented in electronic prescription systems in several countries15,16 The novelty of this study lies in the use of an ADE detection tool in an ED to identify patients that could benefit from personalized pharmaceutic care interventions aimed at reducing their high risk for repeated consultations and hospital readmissions3,4.

Secondary prevention programs for patients at a high risk of ADEs have demonstrated to be effective in preventing ED and hospital re-admissions5,12. The workload of EDs, which provide medical care 24 h a day, prevents ADEs from being appropriately identified. The use of ADE identification tools would enable early intervention after discharge and facilitate the development of ADE prevention programs. Secondary prevention measures were adopted for the 310 patients who were identified to have experienced an ADE (medication reconciliation and patient-centered medication review, telephonic call at 48 h, and communication with the treating healthcare provider).

Based on the results obtained, the diagnostic codes recorded at discharge associated with diabetes and glycemic abnormalities (E10.1, E10.2), as well as with hypertensive crisis (I16.9) had a >70% power to detect consultations related to drug therapy failure. Therefore, these diagnostic codes should be considered as alert diagnostic codes of candidate patients for the implementation of secondary prevention strategies. On another note, an association as low as 30% was observed between K59.0-Constipation and ADEs. However, the high percentage of patients discharged with that diagnosis enabled us to detect a significant number of patients with an ADE.

There were a significant number of cases of drug-induced constipation, which were coded in our study as lack of treatment with laxatives. Chronic treatments for frail patients and opioids are known to be highly anticholinergic and are frequently associated with ED admissions for constipation17,18. Therefore, their study is of special interest. The use of this diagnostic code in specific patient populations (frail, terminal or psychiatric patients) would improve the percentage of ADEs detected. Notably, diagnostic codes D62- Acute posthemorrhagic anemia and I74.3- Embolism and thrombosis of arteries of the lower extremities showed a poor association with ADEs. Therefore, evaluating these patients to improve drug therapies is not cost-effective.

This study also has some limitations. Firstly, as it is a single-center study, the results obtained are constrained to the particularities of the code system used in the center where the study was performed. However, ICD-10 is a universal classification system and the methods used in our study may be a starting point for assessing its repeatability in other centers. In addition, the ICD-10 codes included in the study were selected by a group of experts of the hospital. For such purpose, experts used the data available on the ICD codes most frequently associated with ED admission for an ADE. Less prevalent ICD-10 codes were excluded. There is evidence of an association between other diagnoses and ED admission for ADE19,20. However, those diagnoses were excluded from our study due to their low frequency in our center. Larger studies are needed to address this issue and determine the sensitivity of less frequent diagnostic codes in detecting ADEs. Owing to the methods used in this study, we could not assess the sensitivity of these codes in detecting all patients admitted to ED for an ADE. However, this study made it possible to identify a large number of candidate patients to drug therapy improvement who had not been identified so far.

In summary, ICD-10 codes are a useful tool for the identification of patients admitted to the ED with an ADE. These diagnostic codes can be used to develop tailored secondary prevention interventions to prevent readmissions.

Contribution to the scientific literatureAdverse drug reactions (ADEs) are a frequent cause of admission to emergency departments and are associated with a high percentage of readmissions. Most of patients admitted for this reason are discharged without an appropriate review of their chronic treatment. ICD-10 codes can be useful in the identification of patients who consult for an ADE. These patients could benefit from drug therapy optimization programs and the prevention of ADEs requiring revisits to healthcare centers. In this study, we assessed the capacity of 27 ICD-10 diagnostic codes to detect ED admissions for ADEs. This is a novel approach in the field of emergency care services.

Authorship declaration- •

Jesús Ruiz, Marc Santos, Mireia Puig, María Antonia Mangues, Eduard Gil and Ana Juanes contributed to the conception and design of the study, as well as to data collection, data analysis, interpretation of results, manuscript drafting. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

- •

Laia López and María Piamonte contributed to data collection, data analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript review. They read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (No. IIBSP-COD-2022–40).

FundingNone.